What are we really doing on social media?

The motives and strategies that shape our online presence

This is the third and last post on how coalitional game theory and psychology help us understand aspects of our everyday lives. The two previous posts looked at the dynamics of friendship and our taste for sports. This post is about our online presence on social media.

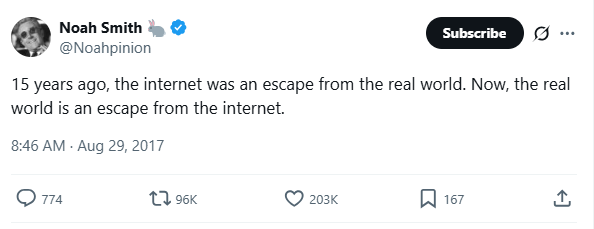

Noah Smith once posted this aphorism that went viral:

It hits the mark because of the importance our online presence has taken in our lives. As most people have joined social media such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and others, it has become pretty difficult not to be online. So what exactly do we do online, and why? Like many aspects of our lives, the underlying motives and strategies we follow are not entirely transparent to us.

In this post, I unpack three layers of strategic considerations shaping what we do when posting on social media platforms: presentation, competition, and coalition building.

The presentation of self online

To understand what we do online, it helps to recall how we already perform in everyday life. In his classic The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956), sociologist Erving Goffman compared our involvement in social settings to theatre. We are engaged in representations where we put the best aspects of ourselves forward, and keep inconvenient elements behind the scenes. Our representation differs between social settings, one can be a father and husband at home, a good office colleague at work, and an entertaining friend with mates.1

Goffman calls the image we cultivate in these settings our face. This is also the logic of the presentation of ourselves online: we curate our photos and the elements of information we publish to curate our public face. Social media are a fairly new setting where we cultivate, the persona we want to be associated with.

Online platforms are distinct theatres, each governed by its own conventions. What works on Instagram is derided on Twitter, and what works on Twitter might raise eyebrows on LinkedIn. Different social platforms act as different social settings, each of them requiring different roles to play: the fun life-loving person on Instagram and Facebook, the witty public commentator on Twitter, the reliable and respected colleague on LinkedIn.

When separate audiences collide, the faces we put out in different contexts often conflict. This is why online context collapse feels awkward:. It happens when, for example, an office colleague follows your Instagram account meant for close friends, or when one of your family members comments on a policy thread you made for the public. The discomfort is not random. It arises because different settings call for different performances, and those performances cannot always be reconciled in one public.

This problem of overlapping audiences isn’t limited to ordinary users. It helps explain why academics often appear relatively boring on social media. If you check out the leading scientific Substacks, you will find out that most of them are not by active researchers.2 Why is that so? A reason is that the kind of presentation and communication strategies that are successful on Substack (e.g. being assertive and authoritative) might interfere with the kinds of strategies that are successful in scientific circles (e.g. being measured and guarded).3

Status games

Goffman did not focus on status. Nonetheless, we can extend his analysis to the way people negotiate their reputation and social standing when cultivating their face. The choreography of our involvement in social interactions is designed to broadcast positive traits (e.g. trustworthiness, conscientiousness, kindness) and high social standing (e.g. prestigious achievements, esteem from other people).

As social media’s importance in our lives has grown, it has become not only a place where we display our status but also one where we can earn it through our actions. The social media currency for success is the popularity of our content reflected in likes, retweets, and followers. Popularity on social media platforms provides prestige, a specific type of status. “Prestige is rooted not in coercion but in admiration, respect, and voluntary deference.” (Dan Williams)

In a social species like ours, social status, our standing in a group, shaped the chances of success of our ancestors. High-status individuals are more likely to be at the centre of strong coalitions, to have friends, allies, and mates. Status is therefore one of the things that our brain likely identifies as a primary reward, and it is, as a result, a major driver of our behaviour.

A study by neuroscientists (Lindström et al., 2021) found that people space their engagement on social media to maximise their social rewards, such as likes and retweets. Another study found that after going viral, posters “more than double their rate of content production for a month”.4

Competition: bidding for relevance

Beyond self-presentation lies another layer of social activity: competition for attention. Many social media users do not simply curate their profiles and presentation of their personal information, but also opt to create content on social media. These content creators generate such diverse content, from cat videos to political analyses, that it might seem vain to identify a unifying principle behind these different contents. However, an understanding of communication games helps us see one important commonality behind how people engage on social media.

Relevance=surprise+value

Any type of post on social media is a bid for the attention of the potential audience. This bid relies on a claim of relevance: a claim that the post has interesting content for the audience. What is interesting content? It is content that contains valuable information for the audience.

Information seems like a mysterious concept, but a simple way to define it—in line with formal theories of information—is as surprise.5 Information is what changes your beliefs. If I tell you, “I have something important to tell you, the Earth is round.” You’ll be puzzled, as I asked your attention to tell you something that both you and I—in all likelihood—take for granted. If I tell you, “The Earth’s shape bulges at the Equator, it is called an oblate spheroid”, that is more likely to be informative, because it is a fact less widely known. If you were not aware of the fact, or not aware of the technical name for that shape, my statement has updated your knowledge about the world.6 A post/message is informative only to the extent that it contains such an element of surprise, something that changes your beliefs.

Yet informativeness alone is not enough to be interesting. The number of informative messages that someone could provide is nearly infinite. When talking to you, I could tell you about the name of my grandmother’s cat, about the temperature right now in Oguni, a small Japanese town of 6,000 inhabitants, or about the number of prepositions in Tok Pisin, one of the 840 languages spoken in Papua New Guinea. While these pieces of information will change your beliefs, you would, in all likelihood, have no use for them.

Our time is limited, therefore a bid for attention by a speaker relies on the underlying claim that the information provided will be valuable and worth the time you’ll invest in considering it. If I tell you “The Earth’s shape bulges at the Equator, it’s called an oblate spheroid” I must assume you are interested in this kind of nerdy factoid. If I just say that out of the blue to one of my random acquaintances who has no known interest in scientific facts, my bid for attention might be perceived as misplaced. If I tend to do such things often, I might come out as lacking social skills.7

Taken together, these observations reveal a unifying principle behind all posting on social media. The poster makes a bid for the audience's attention, claiming that the content is relevant: surprising (given what the audience knows) and valuable (useful or entertaining given the audience’s goals and preferences). This principle works for those posting information on news events that the audience is interested in or political analyses that bring new perspectives the audience might be curious about. It also works for cat videos: it only works to the extent that the video contains an element of surprise, something unusual that you like, given your preference or curiosity.

Competition in the marketplace of ideas

Social media platforms create a place where people produce content and bid for the attention of others. We can think of them as a marketplace of ideas, whose inner workings can become clearer when using insights from how standard markets work.8

First, like on any market, there is no free lunch, no easy gains to be made. When bidding for the attention of an audience, the key challenge posters face is that being relevant is difficult. To start with, relevance requires your content to be surprising, and surprising an audience all the time is hard.

A first possibility is that you have greater knowledge than your audience and, by imparting this knowledge to your audience, you can regularly provide relevant content. Unfortunately, as you do so, you progressively reduce the gap in knowledge between you and your audience, and what you have to say might become less surprising over time. This is all the more the case because if what you said was initially very relevant, other people might repeat or repackage your insights, increasing their familiarity within the population.

A second possibility is that you have found a recipe to produce novel and valued content. It might be political analyses generated from a specific point of view, cat videos made in a format people enjoy, or novels written with a new and entertaining style. The difficulty here is that if your content is successful, other posters will replicate it and the unique novelty of your content will be progressively diluted.

Producing outstanding content on social media can be thought of as beating the marketplace of ideas: producing more surprising and valuable content than what others are producing. A key insight for economics is that consistently overachieving in a competitive market is hard.

Risk-return trade-off in the marketplace of ideas

Relevance requires content to be surprising and valuable. However, it is often unclear what people will like. The distribution of private tastes is hard to observe, and public statements about tastes are often off because people misrepresent them. As a result, content creators typically face uncertainty9 about whether their content will be highly successful. People are often surprised by their posts going viral while some of what they thought were good posts did not resonate much with their audience.

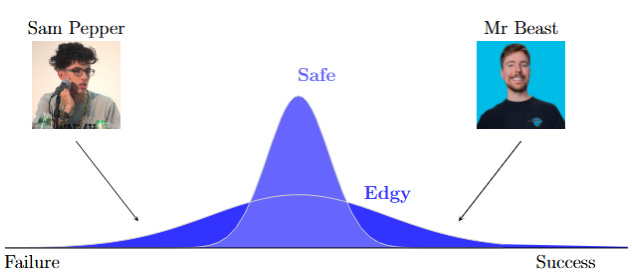

Although success is unpredictable, creators can choose the level of uncertainty that they want to face.

Some content is known to be of interest to a large number of people. The problem is that the knowledge that it is the case is typically widespread. So many people can, like you, safely offer this kind of content, and you’ll face a lot of competition. If many people offer this content, the audience also expects to see this content and, therefore, will not be very surprised when seeing you post something like that. “Safe” content, that you are confident will meet positive approval, is, for these reasons, likely to have only moderate appeal because what you post is unlikely to stand out as interesting and surprising for the audience.

By contrast, some content is inherently uncertain in its appeal. Because creators want to take risks to have a shot at being successful, they often test known boundaries. This type of content is often called “edgy”. The uncertainty here means the content can generate widely different responses. At one end, you might find yourself to be the only one to have offered some highly surprising content that people find useful. At the other end, you might stand out as having posted some content that people, contrary to what you were hoping, really disliked. Posting edgy content is therefore a risky strategy.

On the marketplace of ideas, sellers face, therefore, a risk-return trade-off.10 Posters can choose a strategy along a continuum between a low-risk, low expected gain strategy and a high-risk, high expected gain strategy. This risk-return trade-off is at the centre of social media posters’ experience. There is no reliable way to create highly relevant (valuable and surprising) content; to have a shot at standing out from the crowd of content creators requires trying novel ideas, the appeal of which is not guaranteed a priori.

The highly successful social media contributors have typically made their trade in generating new and different types of content that find broad appeal. However, at the start, they could not be sure it would work, and for all those you saw succeeding, there are the many who tried outlandish content and saw people turn away from them as a result.

To chase fame and glory, one has to generate content that might stand out a lot, and so maximum surprise to a large number is what people ought to aim for. This leads to some outstanding successes on the one hand and a large number of failures on the other hand.11

Risky content can take many forms. Video game streamers may be tempted to cut some corners and bend some rules to generate more surprising videos (e.g. speed runs), but risk being called out and shamed when found out. Fashion influencers may be tempted to suggest radical new things that might fall flat and be perceived as weird instead of amazing. Political influencers may be playing with the Overton window to get attention, but risk being seen as having crossed a line.

The challenge of staying relevant

Becoming highly relevant is hard. Being consistently highly relevant is even harder. The key challenge here is to repeatedly generate highly surprising and useful content. If you became famous for posting a type of content, can you produce additional novel content that is surprising and useful to the same extent? Sometimes success is just singular; sometimes it comes from a kind of novel recipe you have found and that you can develop in different ways to produce more content. If this recipe is easy for others to reverse engineer, your new style of content is going to be quickly imitated and reproduced over and over, until its appeal and novelty dry out. If you are lucky, your novelty is attached to some specific skill you have that is hard to replicate.

The pitfall of clickbait strategies. In the bid for relevance, there is a temptation to overclaim the relevance of some content. Clickbait is a strategy consisting of generating traffic towards one's content by overclaiming how informative and useful it will be. Headlines such as “You won’t believe what happened next” are common because they promise highly surprising and interesting content. Such strategies can easily work in the short term when the audience is naive and accepts the promises of relevance at face value. However, audiences learn and progressively dismiss clickbait messages and clickbait posters. Clickbait strategies can therefore be a long-term trap. They work in the short term to attract eyeballs but have a reputational cost in the long term that is progressively reflected in an erosion of the appeal of one’s content.

A reverse strategy is to post high-quality content that is not overly advertised and where the audience finds that there is more than meets the eye. Such a slow-burning strategy might lead to a lower initial growth but to positive reputational gains that are effective in the long term.

The anxiety of becoming passé, of losing one’s mojo, is widespread among content creators. In the quest to stay relevant, the risk is to overplay the edgy strategy, to “jump the shark”, to create content that visibly tries too hard to stand out and fails to appeal to the audience.

Coalitions: building an audience

These dynamics—presentation and competition—take place within a social environment. To be popular, one has to find a crowd interested in one’s content. This crowd forms by joining us for the content we produce. Chasing popularity on social media is a coalitional game.12

Content creators and those approving their content can be thought of as forming a coalition. This is all the more the case given that, beyond each post, people create communities of followers looking to follow their content regularly.

Building a community

A recipe for long-term success as a social media creator is to go beyond narrowly “commercial” exchanges of content for attention to build a community that thinks they belong to a special group.13

In situations where groups already exist around specific tastes, the safe vs edgy choice in terms of strategy often takes the form of choosing whether to pander to the known taste of a group to get it as an audience or whether to propose new takes with the potential to reshape a group’s narrative or to create a new group around a new narrative.

The second strategy is a high-risk/high-reward strategy. Most often, it is unsuccessful, but the ones who succeed suddenly get a leading position in terms of prestige as thought leaders.

Relevance on social media is the result of social dynamics

A coalitional perspective helps us appreciate that relevance depends on social dynamics: what others believe and what they believe others believe.

To start with, interest in a piece of content often depends not just on the content itself, but on who produced it. For instance, if Brad Pitt posts a funny joke on social media, I might find it worth reposting because I know others might find it interesting. It’s not just about the joke; it’s about its source, a famous actor. If the same joke comes from someone who isn’t famous, I might not repost it because I don’t think others would care. Hence, for the same content, Brad Pitt might get likes and retweets, while someone who isn’t famous would not.

Furthermore, what people can openly admit as interesting depends on what they believe other people will praise or criticise. In the same way as posters care about their self-presentation, the audience’s visible reaction, such as likes and retweets, are also the result of strategies of self-presentation. Hence, we have performative approval: you might approve some things publicly because you think others will appreciate you for doing so—either because it indicates your expertise, acumen, or moral rectitude.

There are also things that people agree on but won’t publicly support because they fear the judgement of their fellow coalition members. Tim Kuran famously analysed the differences between private and public views in his book Private Truths, Public Lies (1998). In it, he describes the phenomenon of belief falsification, where people publicly display beliefs they actually do not hold.

A good illustration is the recent admission by Malcom Gladwell of having publicly misrepresented his personal views on the question of whether trans-women should have the right to participate in female sports, by fear of expressing his actual views on the topic. Another reflection of these considerations is the fact, as claimed by Elon Musk, that the making of likes private increased their number, suggesting that there was a substantial amount of self-censoring before.

When a lot of people do not dare to approve publicly of some discourse they think others may not approve, you can have a situation of pluralistic ignorance: when most people are unaware that a majority of people hold private views similar to them. Pluralistic ignorance can be broken by events that make private views common knowledge: a protest, a crowd of anonymous participants cheering, or an election where private votes are secret.

The tale of the emperor who had no clothes is a canonical example of this process. In that tale, everybody could see with their own eyes that the emperor was naked, but nobody dared say it for fear they might be the only ones. Once an innocent kid stated the obvious truth aloud, not only did everybody know they were not alone, but they also knew that everybody knew they were not alone. This gave them the confidence to voice their opinion aloud.

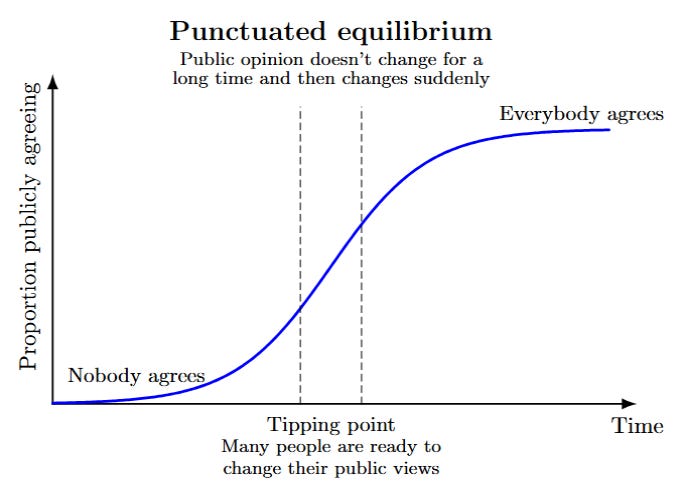

Such dynamics help explain why changes in public views often take the form of a punctuated equilibrium: change seems slow if not non-existent for a long time as people do not dare to state their private views when they think they are in a minority but then changes comes up quickly around tipping points once people realise their views are not so much in a minority as they thought.14

These beliefs about others’ beliefs and the confidence they give to people to support or not non-consensual topics are often summarised with the term vibe. The ability to perceive the vibe, to understand the zeitgeist, to read the room, is a key skill for would-be content creators when deciding the degree of edginess of their communication. Fortune might reward the brave who happens to be the first to state that the emperor has no clothes when everybody is very much willing to state the same once they are confident others will. But many have paid a hefty price for stating things that did not fit the current vibe, sometimes even things that most people agreed with privately but did not feel confident enough to support publicly.15

Being relevant, therefore, doesn’t mean having the best content in some objective sense. It is having surprising and interesting content, given the existing beliefs and preferences of the audience. There is a risk in being too innovative with content that will eventually become popular, but is put forward at a time when the audience is not ready for it.16

Loyalty incentives and audience capture

Because of our coalitional psychology, as soon as we contribute in domains where different coalitions are opposed, the content we produce online is first read through the lens of the question: on what side of the divide is this take?

When you have a community of like-minded people following your content, a “safe” strategy is therefore to produce content that you know will please your audience and will be perceived as supporting the cause of the community’s coalition. A content creator might, for instance, find that posting the kind of takes expected by his audience helps secure his standing as a highly regarded commentator in his community. If he has some doubt about the position favoured by his political side, he might hesitate to voice his opinion explicitly for fear of being dumped by his audience. As a consequence, within each coalition, there might be too much self-complacency and too little self-criticism. In some cases, audience capture can lead creators to progressively lower their concern for external reputation to simply cater to the narrow interests and views of their audience.17

An alternative strategy is to risk saying it as it is. If this strategy fails, you will be scolded by your side for lacking loyalty and excluded from your coalition, losing your standing there. But you might also succeed and help generate a new coalition around your view. As it is a risky strategy, not many follow it, and so the rewards can be high. It is also a strategy more likely to be taken by those whose social standing is not entirely based on their narrow coalition and who could still have some social standing after being rejected by their audience.18

Hence, the different strategies followed by online pundits: you have those who totally embrace the cause of a given coalition and produce justifications for it and you have those who choose to adopt a frequent contrarian position, daring to say that the emperor is naked on their side of the coalition when everybody else was going along with their coalition narratives. These contrarian posters are risk-takers bidding for alternative coalition formations with new groupings forming around them, standing alone with their search for honesty, instead of blind coalition loyalty. They are hoping to, in the best scenario, ride a tipping point where their contrarian coalition supersedes the currently prevailing coalition.

Why do we care so much about our presence on social media? Why can’t we predict which post will go viral? Why can we be stressed about pressing “send” for some of our posts? All these questions get simple answers when we appreciate that social media are just platforms where people vie for social recognition by bidding for attention. Social recognition is something we deeply care about (even if our account is anonymous!). Because of the competition between content creators, there is no easy way to gain a lot of attention, and people compete to find novel content whose eventual appeal could be large. There is, therefore, a risk-taking choice in social media engagement: how much novelty and edginess to attempt to get a shot at attracting a lot of attention while taking the risk of being received negatively. The nature of this risk is social in nature: we are vying to successfully build coalitions of people approving our content while taking the risk of being negatively judged by many others. These are the games we play on the theatre stage of social media.

References

Baumgartner, F. R. & Jones, B. D. (2009). Agendas and Instability in American Politics (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fang, D., Ke, C., Kubitz, G., Liu, Y., Noe, T. & Page, L. (2024). Winning Ways: How Rank-Based Incentives Shape Risk-Taking Decisions. Oxford: University of Oxford.

Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor.

Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Kuran, T. (1998). Private Truths, Public Lies: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lindström, B., Bellander, M., Schultner, D. T., Chang, A., Tobler, P. N. & Amodio, D. M. (2021). A Computational Reward Learning Account of Social Media Engagement. Nature Communications, 12(1), 1311.

Lindley, D. V. (1956). On a Measure of the Information Provided by an Experiment. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 27(4), 986–1005.

Schultner, D. T., Chang, A., Tobler, P. N. & Amodio, D. M. (2021). A Computational Reward Learning Account of Social Media. Nature Communications, 12(1), 1311.

Shapley, L. S. & Shubik, M. (1969). On Market Games. Journal of Economic Theory, 1(1), 9–25.

Srinivasan, K. (2023). Paying Attention. Technical Report 2023. Mimeo, University of Chicago.

te Velde, V. (2022). Heterogeneous Norms: Social Image and Social Pressure When People Disagree. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 194, 319–340.

The differences between these settings explain the frequent uneasiness when they unexpectedly collide, like when a family member comes to get you at work, or joins you with your group of friends.

A few of them are from anonymous accounts who might be academics avoiding the collision of their reputation across the public and scientific spheres.

Clear and bold takes are more likely to attract the attention of a broad audience and non-academics are more able and willing to generate this kind of communication, not because scientists can’t but often because they self-censor. In science, there is a huge premium on establishing a pristine reputation of intellectual rigour. Hence (active) scientists are careful neither to say something wrong nor to say something without the right degree of qualification of their degree of certainty to protect themselves from accusations of having overstated something. This makes scientists the masters of hedging.

A famous apocryphal quote attributed to President Truman reflects the frustration people who need practically usable insights might feel when discussing with scientists overly cautious not to lose their reputation for intellectual rigour:

Give me a one-handed economist! All my economists say, ‘On the one hand … on the other hand.’

Lindstrom et al. (2021) and Srinivasan (2023), respectively.

Lindley (1956),

Knowledge is just beliefs that are held with an extremely high degree of confidence.

This interaction from The Big Bang Theory illustrates how misplaced bids for attention, that provide content that is informative but not valuable to the listeners, are a reflection of poor social skills:

The marketplace of ideas is a notion usually used to describe the production and exchange of intellectual and political ideas. I am extending its use here to think of all the production and publication of all informational content bidding for our attention.

The economist reader might recognise here a hint at Knight’s famous description of entrepreneurs facing radical uncertainty when engaging in new ventures.

Here again, we gain insights from traditional markets. While it is hard to beat financial markets consistently, it is possible to get higher expected returns by making more risky investments. The efficiency of markets implies that: for a degree of risk you are willing to take, there is a level of return you can expect to gain on that market. Doing better than the market is hard for a given level of risk, but you can nonetheless vary your expected returns by taking more or less risk.

The optimal strategy in competitions where the rewards are concentrated at the top of the success ladder (e.g. winner-take-all all competitions, stardom) is to adopt a risky strategy generating a skewed distribution. Unlike the illustration in the post with Sam Pepper and Mr Beast, which presents a symmetric distribution between success and failure, the optimal strategy (in equilibrium) is to produce content that has a lot chance of not being successful but has some chance of being massively successful. See our research on this question (Fang et al. 2024).

To the economist reader: a coalition is defined as a group and an allocation of the group’s value/resources among participants. In a marketplace of goods, a group of buyers and a seller reallocate money and goods between them. In a marketplace of ideas, a group of buyers (followers) and a seller (content creator) reallocate information and prestige in the form of social approval.

Note that this coalitional logic is not restricted to the marketplace of ideas. Firms selling goods often do not want just to sell you a product, they want you to embrace a brand and join a community of like-minded people who do so.

See Baumgartner and Jones (2009) for the application of the notion of punctuated equilibrium to politics and te Velde (2022) for its specific application to changes in public opinion along the line I described.

A good illustration of this logic is the dynamic of fame of musicians and singers (you could also apply it to book writers and other content creators). Some singers release a hit song that is unique in its style and garners broad appeal. Then they are never able to reproduce anything equivalent to their initial success. In their search for novel content they had by chance stumbled on a golden nugget but they did not have a reliable recipe to find more. Other musicians come with a unique style which is different and appealing; these musicians are able to apply this style in different pieces that garner broad appeal. If this style is tightly linked to unique abilities (e.g. a unique voice style), they might be able to stay unique for longer than if their style can be quickly copied.

See, for instance, my discussion of what happened with the split in the MAGA coalition with the Epstein files.

That’s a deep question! I think most of us use social media to connect, share, or just escape for a bit even if we don’t always realize it. Sometimes I catch myself scrolling food posts like the Texas Roadhouse menu, just for the comfort of seeing delicious meals. It’s funny how online spaces mix connection, curiosity, and craving all at once. You can also explore this site https://thetexasroadhousemenu.com/

Thanks for sharing!