The truth about sport

Why we really care about it

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern version of the Olympic Games, described sport in these poetic terms:

O Sport, you are beauty! You create harmony, you fill movement with rhythm, you make strength gracious, and you lend power to supple things.

People often argue that the beauty of the game is a critical, if not the main, reason for watching sports. Indeed, the most globally followed game, football—the one you play with your feet—is commonly described as “the beautiful game”.1 Talented players, such as Maradona or Roger Federer, have been described as “artists”.2

Is “beauty” why we care about sports? Is it why people are willing to pay serious money to attend matches in stadiums, take pay-TV subscriptions, buy shirts and merchandise and sometimes even plane tickets to see matches? If you are a regular reader of this Substack, you suspect the answer is no, and it is.

Sports attract our attention because they are status games, and status is something we care about greatly.

Status games

Why do people run very fast? Like, Mo Farah – what’s the point? And why do people invest a significant amount of money, time and discomfort in watching these very fast runners? Staring and screaming from their plastic bucketseats in those awful concrete arenas, they seem to care a lot about how many milliseconds faster this one ran than that one. Why? And while we’re at it, what’s the point of football? [...]

This is how all the games people play for fun function: by exploiting the neural circuitry that evolved to play the status game, which is the original game, and the greatest game of all. — Storr (2021)

Status within the community

Competing to demonstrate one’s physical prowess in an environment made safe by formal rules codifying behaviour and prohibiting violent escalation.

Many sport-like contests likely grew out of competitive displays in skills useful for hunting or fighting—running, throwing, wrestling, stick-fighting—because these performances broadcast stamina, coordination, and nerve. Cross-cultural work shows that games of physical skill often model combat or hunting.3 Contests in agility or coordination can be reasonably informative about a person’s general condition (endurance, strength, reaction speed).4

Physical competitions are, therefore, historically a way for men, and sometimes women, to display their fitness to members of the other gender. Ritualised games emerge with the codification of formal rules prohibiting violent escalation, making these competitions a safe and low-risk environment to settle hierarchies of status between participants.

Status from success in sports competition comes in the form of prestige, a type of social recognition in which one’s worth is publicly acknowledged. While modern sports pay top athletes handsomely in many disciplines, prestige is typically the main driver of their motivation. It explains why players continue to chase records even after they have already become wealthy.

Money does matter, but often more as a signal of worth than as a direct goal. This is perfectly summarised in the movie Moneyball when coach Billy is considering an offer from the Red Sox with the biggest pay package in history for a baseball coach.

PETER: You’re not doing it for the money.

BILLY: I’m not?

PETER: You’re doing it for what the money says. It says what it says to any player who gets big money: that they’re worth it.

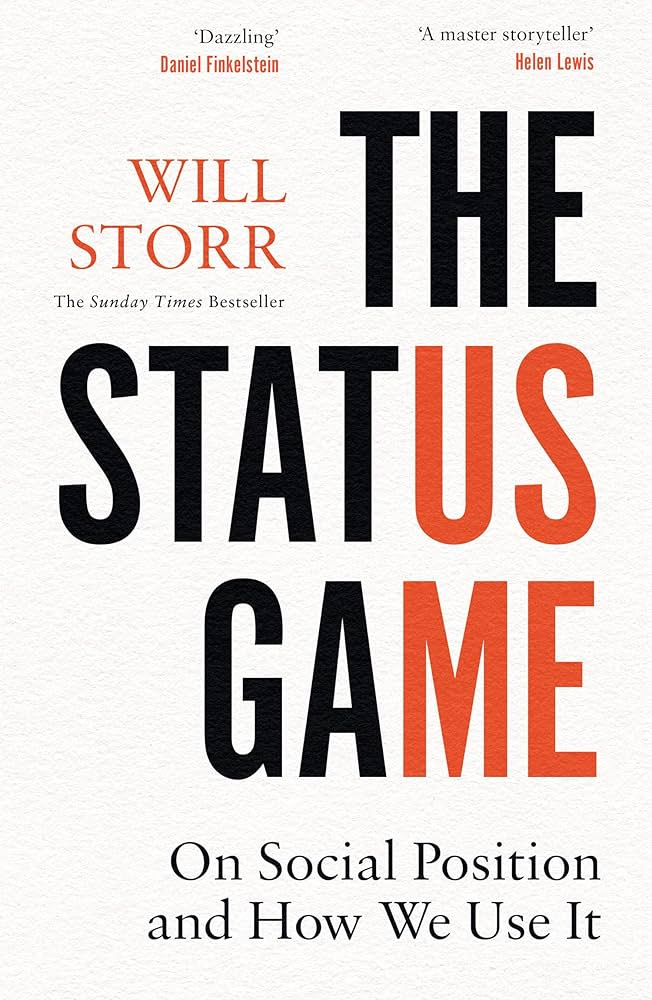

In his book Status Games, Will Storr makes the same point:

We’re used to thinking of money and power as principal motivating forces of life. But they’re symbols we use to measure status. […] the desire for wealth is not fundamental. Status is the original form of currency, and the one that matters most. Studies show a majority of employees would accept a higher-status job title over a pay rise. — Storr (2021)

Status games attract attention across the community. Younger members are often prospective participants in the near future. Members of the other gender can gather useful information to form preferences over the competitors. The friends and kin of participants see their own social standing influenced by the outcome of the competition (e.g., being the friend of a winner whose rising status also raises yours). For those who are neither kin nor friend, the outcome of the competition is informative about who is going to be a valuable coalition partner (not only because of their athletic qualities but also because successful participants rise in standing and therefore become more sought after as coalition members).5

Hence, status competitions are not just interesting for the participants but for large segments of the community. Indeed, it is only because they are interesting to many people that they confer prestige. Winning obscure competitions does not increase status much.

Our psychology reflects this informational value: our curiosity is triggered by physical competitions as status games.

Status between groups

This first explanation leaves some facts about how humans engage with sports unanswered. A noticeable fraction of supporters seem to have motivations that go beyond simply watching the game.

Sports fans often spend a substantial amount of money to display visible signs of support for their team. What does this have to do with the “beauty” of sports?

In some cases, the interest of supporters in the action on the pitch seems unclear. Tifos (groups of die-hard football supporters) often feature a leading figure— the Capo—who leads songs and chants, facing the crowd and therefore not even watching the game. What’s the point of paying for a ticket to be in the stadium if not to watch the match?

Supporters of sporting teams sometimes turn to physical violence. Hooliganism has been a major issue in European football since the 1960s, and especially in the 1970s and 1980s. Cases of violent clashes between groups of supporters have also been observed in other sports such as tennis or ice hockey. In an extreme and somewhat odd variant, Russian football supporters organise codified street fights outside stadiums, an activity described as Stenka na stenku.

What is the point of these violent conflicts? Why are they related to sports events?

The answer is that sports are not just ritualised status games between individuals, but also status games between groups.

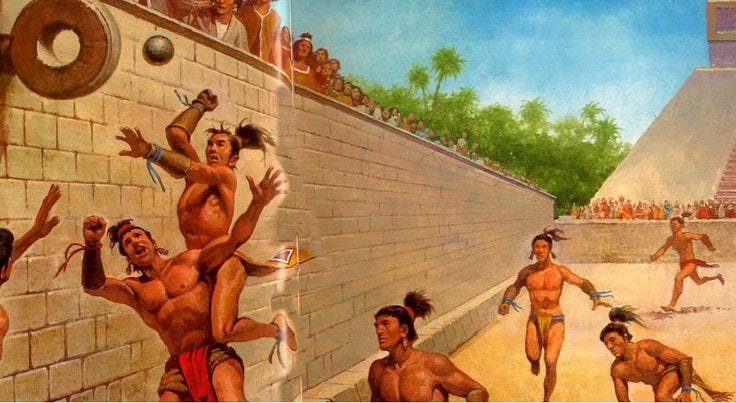

Anthropological evidence points to sports-like competitions being used as mock conflicts between communities. In North America, prior to and during the early colonial period, lacrosse served as a substitute for warfare between tribes and was sometimes used to settle territorial disputes.6 In Sudan, the Nuba, a relatively isolated population living in small-scale communities, were observed in the 1940s by anthropologist Nadel holding inter-hill wrestling and stick-fighting tournaments. These competitions pitted neighbouring communities against one another.7 In Mongolia, from the seventeenth century through the early twentieth century, the Danshig Naadam (a festival of the “three manly games” of wrestling, horse racing, and archery) was a major public event, featuring rivalries between localities.

Sports tap into our coalitional psychology and trigger emotions of social bonds, whereby we identify with our group. Teams and individual athletes are explicitly (e.g. football) or de facto (e.g. tennis) representatives of cities and countries. The compatriots of a team that wins the World Cup benefit from the higher standing it gives to the whole country as a whole.

You might reasonably think that this “benefit” is practically very small. What is it? Having your chest puffed up slightly when talking about the World Cup if your team has won? It might seem like a fairly inconsequential outcome. But people do care about their country’s symbolic standing relative to others, whether it is in GDP rankings, in the number of atomic bombs, or on the Olympic medal tally.

In a survey of 1,500 US adults this year, 76% respondents indicated that it is moderately to extremely important that Team USA is successful in the Olympics, and 46% of them supported using federal funds to help finance college sports programs to develop the national Olympic team. Politicians are well aware of these preferences and allocate substantial resources to improve the achievements of national athletes.8

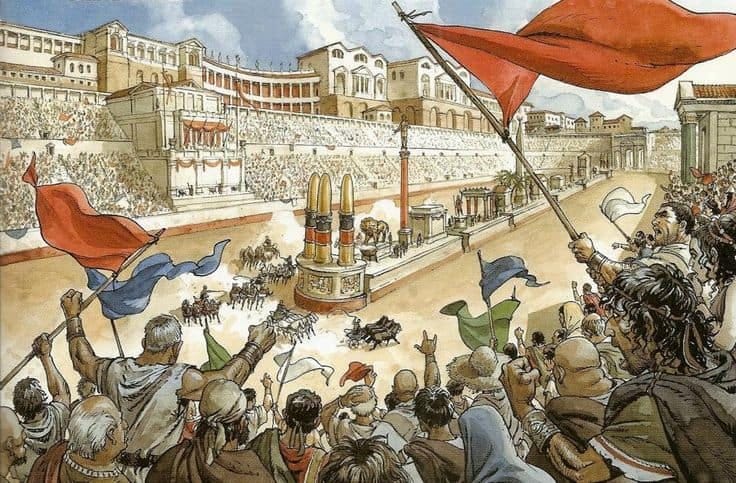

Sports do not only rest on the support of existing groups; they can also reinforce feelings of group identity and even create entirely new ones around the teams themselves. Between the 4th and 7th centuries, life in Constantinople was marked by the importance of chariot races, with four factions, the Reds, Blues, Greens, and Whites, emerging as enduring group identities that often divided the city and were sometimes embroiled in violent clashes.9

The real reasons we enjoy sports

The fact that sports are status games is the real reason they attract so much attention and passion. It is why people watch lagging online streams of matches and follow live score updates on their phones when they cannot see the games. It is not the “beauty” of sports that pulls us towards them. Indeed, even our feelings that some sporting actions are beautiful can be explained as a reflection of sports being status games: beautiful actions are those that seem extremely hard to execute and display exceptional degrees of coordination and skill. No action that could be executed easily by anyone would be described as beautiful.

Many other status games exist besides sports (any social activity where people compete to be recognised or famous). The particular popularity of sports among the many possible status games may boil down to simple reasons. First, caring about physical prowess goes back far into our ancestral times. We may care more about success in sports than in board games or spelling bees because sports tap into more entrenched preferences: we evolved to be curious about and interested in physical contests and finding out who is best at it.

Second, compared to other social activities, sports are highly observable and provide fairly objective ways to determine who did best. Many performances in social life give noisier signals because the actions leading to them are imperfectly observed, and because people might face different conditions that advantage or disadvantage them. It is harder to design a competition to identify who is best at making money than to identify who runs the fastest.

Most information about many achievements is also imperfectly shared in the community. Alice might think Bob’s work in the company is very good, while Candice knows that his achievements are due to good luck. In comparison, something like a race makes differences in achievement almost perfectly observable and common knowledge. Sports competitions are very informative about the participants’ abilities and about the community’s beliefs about these abilities. It is this high degree of informativeness, and the quick resolution of uncertainty, that attracts our attention.

Gender differences in sport appeal

This reality of sports, and why they are popular, helps explain why there is a gap in popularity between men’s and women’s sports in favour of men. In the culture war between right and left, you often hear two opposing types of explanations.

Sexism?

On the left, the explanation is that sexism is to blame. People are socialised to see sport as a male-coded activity, and as a result, they demean the achievements of female athletes.

I don’t think it’s a supercomplex issue. There’s plenty of money being invested all over the place in men’s sports, so until somebody tells me something that makes more sense, sexism is what we’re left with. — Rapinoe in a NYT interview

The fact that sexism has historically played a role, and still exists to some extent, cannot be denied. But whether it is the driving factor behind the large differences in popularity between men’s and women’s sports is another question.

A first difficulty with this explanation is what people say about women’s sports. The sexist disparagement of women’s sports is no longer in vogue. In a 2023 poll in the US, 51% of women and 48% of men stated that they wanted to see more media exposure for women’s sports (with only 12% and 16% disagreeing, respectively). Among sports fans, the share rose to 60% (with only 11% disagreeing). Hence, if sexism is driving the variations in popularity, it must be somewhat covert.

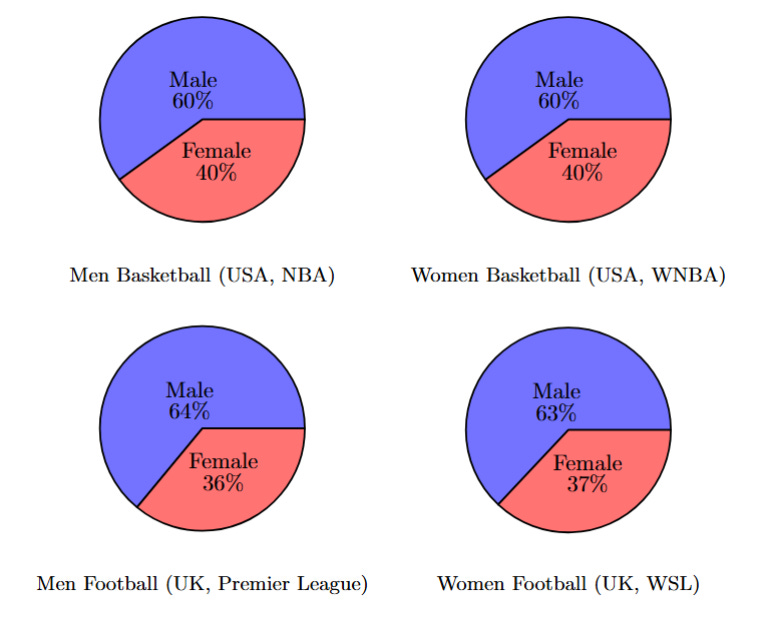

Another difficulty with this explanation is what people do in regard to women’s sports. Data indicates that interest is similarly distributed between men and women. While men form the majority of sports viewers overall, the proportion of men and women watching men’s and women’s sports is similar. It is not the case that men watch men’s sports and then consciously choose not to watch women’s sports. Indeed, because men’s sports attract larger audiences, more women watch men’s sports than women’s sports.10 If the explanation rests purely on artificial socialisation, men and women would have been equally socialised to disregard women’s sport.

Differences in athletic quality?

On the other hand, the lower popularity of women’s sports is often explained by the lower athletic performances of women. Sports journalist Jeff Pearlman, for instance, wrote:

As blessed as women like Parker and Lauren Jackson and Diana Taurasi are at basketball, their skills are not in visual demand. Basketball fans want to see LeBron James dunk and Josh Smith soar through the air and Ron Artest lock down on an opposing scorer. — Pearlman in Sport Insider

I think this explanation also misses the mark. Obviously, men and women differ significantly in average performance in most sports. This is a truth universally acknowledged, outside of some schools of gender studies. But, as I pointed out above, the beauty of athletic performance is not the main driver of why people watch sports.

Indeed, I’ll make what you might find a surprising statement: it is hard for an external viewer to assess the objective level of performance of top players. Even the lowest-ranked athlete in a professional league is head and shoulders above the average viewer in terms of performance. Without deep expertise in the game, it is typically hard to judge how “good” they are just by watching them. A great example was a street experiment inviting people to try reproducing Ronaldo’s vertical leap for a header. It was only by attempting such a feat that lay participants realised just how outstanding Cristiano’s performance was.

Differences in quality are mostly revealed to viewers when athletes of different levels play against each other. When players are separated into leagues, it becomes harder for a viewer to identify differences across leagues. Even though women are less athletic than men in professional sports, they are still very athletic. Since they play in women’s leagues, the visual difference between leagues is not always striking. It is therefore not clear that this difference, as perceived by viewers, drives the lower popularity of women’s sports.11

A good illustration of this comes from a trick used in a French advertisement for women’s football. The ad featured what appeared to be impressive shots by top male players from the World Cup–winning team… only to later reveal that the moves had actually been performed by female players, digitally morphed into the star male players. The trick worked because the moves of the female players looked convincing enough not to betray that they were not from the male stars.12

Another issue with the “athletic quality” explanation is that second-tier male leagues and even amateur leagues still attract notable audiences despite the fact that their athletic performance is substantially lower. In the US, for example, college sports attract massive audiences and are broadcast on pay-TV. Given the large number of matches from top professional leagues, why would people devote time to lower-level matches if their main motivation were to watch the best athletic performances?

I see the explanation based on athletic skill differences as a likely artificial justification, relying on the mistaken idea that we watch sports primarily for the beauty of the action.

The gendered nature of status games

Taking the perspective that sports trigger our curiosity and passion because they are status games that determine hierarchies of status within and between groups, the gender difference in sports popularity has a straightforward explanation. Sports are competitions in a domain where status games have historically taken place primarily between men: physical prowess. The attractiveness of men is more closely tied to their athleticism and agility than is the case for women.13 Hence, both men’s and women’s curiosity is more strongly drawn to physical contests between men.

This is not to say there is no interest in women’s sports, only that men’s competitions have an edge in attracting viewers willing to spend time and resources to follow them. Making this observation does not imply that men’s sports are “better” or more “important.” It is not a value judgement. Finally, it does not settle the question of how much women’s sports should be supported or how women professional athletes should be remunerated relative to men. Answering that question requires something more: a normative theory of how resources should be allocated in society.14

At face value, humans spend a surprising amount of time and resources watching sports. What is it about people pushing a ball across a field or trying to run a few fractions of a second faster than others? As so often, the social narratives offered to explain behaviour embellish motives and mask the underlying drivers. In the case of sports, it is often said that the beauty of athletic performance is what fuels interest. In reality, the reason why sports attract so much attention is that they are dramatic status games with highly visible and unambiguous resolutions of uncertainty in a domain that has long fascinated human communities: identifying the individuals with the highest athletic skills.

When taking the form of team contests, sports become a simulacrum of intergroup conflict, with the outcome determining not only the athlete’s status in the form of prestige but also the status of the group they represent compared to others. It taps into our tribal feelings of identity and loyalty. Whether the game is beautiful (or even fair) typically matters less to viewers than the outcome—who wins.

References

Atwood, C.P. (2004) Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York: Facts on File.

Buss, D.M. (1989) ‘Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(1), pp. 1–14.

Hands, B., McIntyre, F. and Parker, H. (2018) ‘The general motor ability hypothesis: An old idea revisited’, Perceptual and Motor Skills, 125(2), pp. 213–233.

Nadel, S.F. (1947) The Nuba: An anthropological study of the hill tribes in Kordofan. London: Oxford University Press.

Nevill, A.M., Balmer, N.J. and Winter, E.M. (2009) ‘Why Great Britain’s success in Beijing could have been anticipated and why it should continue beyond 2012’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(14), pp. 1108–1110.

Roberts, J.M., Arth, M.J. and Bush, R.R. (1959) ‘Games in culture’, American Anthropologist, 61(4), pp. 597–605.

Schelling, T.C. (1960) The Strategy of Conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sell, A., Lukaszewski, A.W. and Townsley, M. (2017) ‘Cues of upper body strength account for most of the variance in men’s bodily attractiveness’, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 284(1869), p. 20171819.

Storr, W. (2021) The Status Game: On Human Life and How to Play It. London: HarperCollins.

Vennum, T. (1994) American Indian Lacrosse: Little Brother of War. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Weege, B., Pham, M.N., Shackelford, T.K. and Fink, B. (2015) ‘Physical strength and dance attractiveness: Further evidence for an association in men, but not in women’, American Journal of Human Biology, 27(5), pp. 728–730.

This expression, coined by a British journalist, was adopted and popularised by Pelé, the most famous footballer of all time, in his autobiography My Life and the Beautiful Game (1977).

The anthropologists Roberts, Arth, and Bush defined three types of games according to the type of skills they put on display:

It is also evident that most games are models of various cultural activities. Many games of physical skill simulate combat or hunting, as in boxing and competitive trap shooting. Games of strategy may simulate chase, hunt, or war activities, as in backgammon, fox and geese, or chess. The relationship between games of chance and divining (ultimately a religious activity) is well known. In instances where a game does not simulate a current cultural activity, it will be found that the games ancestral to it were more clearly models. — Roberts, Arth and Bush (1959)

See Hands, MicIntyre, and Parker (2018).

Indeed, even competitions with limited or no informative signal about athletic skills can play this role by making winners focal points (Schelling, 1960) for coalition formation. If John wins against Jake, others may think that others think that others are more likely to pick John as a coalition partner, because they know that others think that others think that way. Hence, even if the competition was not particularly informative about John’s higher abilities relative to Jake’s, it might matter greatly for coalition formation afterwards.

See Vennum (1994)

See Nadel (1947)

The British investment in Olympic sports in anticipation of the 2012’s London Olympics was notable (announced in 2005).

From May 1997 until the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000, £58.9 million was used specifically to support 13 sports. In the 4 years before the Athens Games of 2004, £70 million was invested to support 16 sports, and from 2004 to 2008, a further £235 million was used to support 27 sports up to the Olympic Games in Beijing. In November 2008, the UK Government announced a sum of £550 million to support 30 sports up to the London 2012 Games. — Neil et al, 2009

The circus factions in Constantinople were at first professional racing teams organised around the stables of the Hippodrome, but over time they developed into mass organisations that provided new, enduring identities for large sections of the city’s population. Although all four teams (Reds, Blues, Greens, and Whites) survived into the early Byzantine period, the Reds and Whites became relatively minor by the 5th century, their supporters largely absorbed by the dominant Blues and Greens. The Blues were often linked with aristocratic patrons, while the Greens tended to draw support from artisans and merchants. Far more than sporting clubs, the factions acted as political and religious associations whose clashes culminated in major unrest, such as the Nika Riots of 532, that nearly led to the fall of Justinian.

The improbability of some explanations has been lampooned by social media creators, who point out that people supporting women’s sports as a political cause often do not watch them themselves. For instance, in a 2023 YouTube video, “Can Feminists Name A WNBA Team?”, a man asked apparent left-wing passersby whether female sports should receive more attention. They answered emphatically yes, but were then unable to name any WNBA team when asked.

For example, it is hard to appreciate the performance difference between male and female players in tennis when watching them separately. In 2017, during an NPR interview, John McEnroe described Serena Williams as the greatest female player in history. The following exchange made headlines:

Lulu Garcia‑Navarro (NPR): Some wouldn't qualify it. Some would say she’s the best player in the world. Why qualify it?

John McEnroe: Oh, she’s not—you mean the best player in the world, period.

Garcia‑Navarro: Yeah—best tennis player in the world—you know, why say female player?

McEnroe: Well, because if she was—if she played the men's circuit, she'd be, like, 700 in the world.

McEnroe was heavily criticised for his comment. Leaving aside how it was said, and that it might have felt disrespectful, he is broadly right about the difference in athletic performance between men’s and women’s professional tennis players.

In 1998, during the Australian Open, Venus and Serena Williams (then ranked around the top 20–30) said they could beat any male player outside the top 200. A German player named Karsten Braasch (then ranked 203rd) accepted the challenge. He played one set against each sister: he beat Serena 6–1 and Venus 6–2. In 2020, at the height of her career, Serena Williams stated in a 2013 interview (when she was ranked number 1) that if she were to play Andy Murray (then ranked number 2), she would lose 6–0, 6–0 in five or six minutes.

The fact that some journalists doubt such differences reflects the difficulty of spotting athletic gaps when players compete against others of a similar level. It is much more apparent to viewers when players of very different levels face each other.

One could retort that the French advertisement featuring women footballers only showed a few good shots, and that in a match context, people would more easily notice the difference. While this is likely true, the video at least shows that the top performances of female footballers can be good enough to be confused with men’s performances.

See Buss (1989), Sell, Lukazsweski, and Townsley (2017), Weege et al. (2015).

This very question will be the topic of my next series of posts.

The problem with “status games” as an explanation is that it’s a bit like saying “physics” - it explains too much, and doesn’t help distinguish sport from all cultural activities. To say sport is not about beauty is to imply that fine art isn’t also a status competition, which it certainly is. And what about science? Just the selfless pursuit of knowledge for its own sake? Unmotivated by the desire for status/prestige? Neither art nor science can be explained away by saying they are merely status competitions, and the same is true about sports.

The original "cheerleaders" in US college sports were men, playing the same role as the Capos you mention.