The strategic importance of common knowledge in politics

Explaining the hidden logic behind political rituals, protests, and propaganda

In my previous post, the last of a series on communication games, I explored why we often remain ambiguous to avoid common knowledge. Before my next series of posts—on the psychology of happiness—here is a post looking at situations where common knowledge is, on the contrary, desired for its key strategic role: collective coordination games, prevalent in politics.

Nietzsche famously wrote “Madness is rare in individuals – but in groups, parties, nations, and ages it is the rule.” Collective behaviour is indeed often puzzling. We engage in strange codified public rituals like inaugurations, celebrations, and commemorations. We gather to listen to powerful figures even when they may have little new to say. We join large crowds of strangers and sing together be it a hymn or an anthem.

In his 2001 book Rational Ritual, political scientist Michael Chwe argued that such social rituals play a key role in our social life. They create common knowledge.1

Common knowledge is not just knowing the same thing, it’s knowing that others know it, that they know we know they know, and so on (Geanakoplos, 1992). Chwe’s key insight is that common knowledge facilitates social coordination, so social rituals are designed to generate it.

Why is common knowledge so critical? Because collective actions might only work when people trust that others want to do the same thing and that they are trusted by others to want to do it. In large groups, coordination can be a real challenge. Hume points to this difficulty when describing the organisation of collective action.

Two neighbors may agree to drain a meadow, which they possess in common; because ’tis easy for them to know each others mind, and each may perceive that the immediate consequence of failing in his part is the abandoning of the whole project. But ’tis difficult, and indeed impossible, that a thousand persons shou’d agree in any such action - Hume (1739)

Without common knowledge, I may want to drain the meadow, but I may not be sure enough others do. So I could waste my time if I try. Even if I know that many people want to do it, I may be worried that others may doubt that enough people want to do it and therefore not try. Common knowledge eliminates these risks. We all know we want to drain the meadow, we know others do, we know others know we all want to, and so on.

As common knowledge facilitates collective action, it is a central aim of public communication from both those in power and those seeking it.

Rituals of power

Public ceremonies engineer common knowledge by making everyone witness an event and the fact that the entire public is witnessing it. The painting of The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David illustrates how the centrality of an event in a ceremony allows people to witness it and the fact that it is witnessed by others.

For a leader, especially one like Napoleon lacking a traditional claim to the throne, ensuring common knowledge that he is becoming emperor isn’t just ego-stroking. It can have practical effects and bolster his ability to wield power, give orders and be obeyed. Game theorists Moshe Hoffman and Erez Yoeli explain in their book Hidden Games:

Coronations make clear that everyone will treat the same person as their ruler, follow the ruler’s orders, and punish those who disobey. An event like a coronation is typically open to the public, indeed, efforts are made to ensure that as many spectators as possible can attend. - Hoffman and Yoeli (2022)

This effect of coronations raises the fundamental question of why people obey rulers in the first place. In the 16th century, French magistrate La Boétie highlighted the paradox of “voluntary servitude”:

How is it possible that so many men, so many cities, so many nations sometimes endure a single tyrant, who has no power except that which they give him, who can do them harm only to the extent that they are willing to endure it, and who could do them no harm at all if they did not prefer to suffer everything from him rather than contradict him? - La Boétie (1574)

La Boétie thought people willingly accepted servitude due to habit, learned cowardice and devotion. A century later, Hobbes also observed that authoritarian power relies on people's acceptance:

The power of the mighty hath no foundation but in the opinion and belief of the people. - Hobbes (1680)

And half a century later, Hume added that besides our opinions, what matters are our beliefs about others' opinions.

No man would have any reason to fear the fury of a tyrant, if he had no authority over any but from fear; since, as a single man, his bodily force can reach but a small way, and all the farther power he possesses must be founded either on our own opinion, or on the presumed opinion of others. - Hume (1741)

Indeed, the paradox of authoritarian rule is resolved by understanding it as the equilibrium of a social game. Why don’t you revolt? Because you think others will punish you if you do. Why don’t others revolt? Because they think others (perhaps you) will punish them if they do. This equilibrium is maintained and strengthened by the common knowledge that everybody believes this is what everybody believes.2

The rituals of power—where large masses are involved in publicly witnessing and displaying their loyalty—are therefore a key strategic tool to tighten the power of authoritarian rulers. Privately dissenting citizens can only witness that everybody is willing to go along with this display of loyalty.

In modern democracies, heads of state are most often elected, which confers legitimacy upon them. Nonetheless, the transitions of power are typically occasions for large public ceremonies that help enshrine in public recognition the transfer of power to a new ruler.3

Opposition to power

If common knowledge of loyalty is key to ensuring the coordination on a loyal equilibrium, common knowledge of dissent plays a key role in the unravelling of power, from revolutions to coup d’état.

Protests

Protests and rebellions are collective actions that are less perilous and more likely to be successful with more participants. Thus, they are coordination problems.

Rebelling against a regime is a coordination problem: each person is more willing to show up at a demonstration if many others do, perhaps because success is more likely and getting arrested is less likely. - Chwe (2001)

The ability to create common knowledge of private dissent is therefore a key strategic element in generating a growing dynamic of general dissent. For this reason, public protests and opposition media play a strategic role targeted by authoritarian regimes aiming to prevent rebellions.

Overthrowing a dictatorship is a coordination game, one in which political actors want to join the protests if others are participating and want to stay at home if others stay at home. For this reason, dictatorships prize outward shows of conformity, especially on ritualized public occasions, because such displays strengthen the expectations that keep the system working. Conversely, they heavily regulate public gatherings and mass media because these can be used to create expectations that could undermine the regime. A single radio broadcast is likely to be far more damaging than a banned cassette tape smuggled hand to hand; one public speech to a group is more of a danger than private conversations with an equivalent number of individuals. - Singh (2014)

In authoritarian regimes, due to repression of displays of dissent, dissenters have an interest in pretending to support the regime in public. Economist Timur Kuran calls this preference falsification. When much of the public engages in preference falsification, people can overestimate the proportion truly supporting the regime. It can even lead to situations where a majority opposes the regime but most think the majority supports it. Such situations are labelled pluralistic ignorance (Allport, 1924).

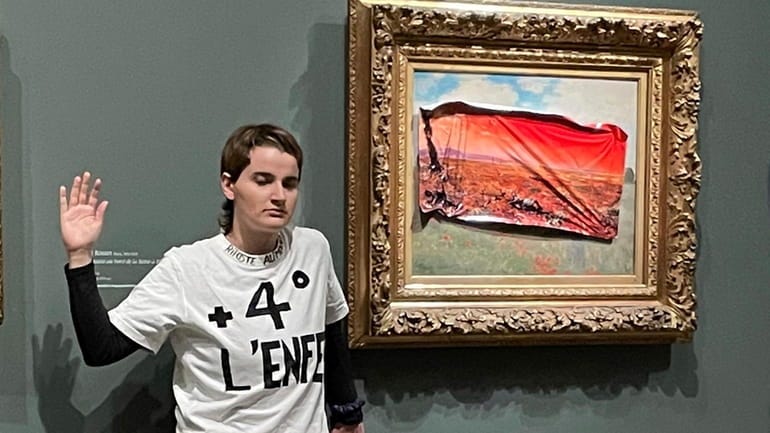

These features of protest games can explain the radical and extreme nature of protest actions. They are designed to generate lots of publicity, thereby creating common knowledge and possibly helping dissidents coordinate on future protests. In addition, they can be informative about the likely proportion of dissidents in the population (Kuran 1989, Bueno de Mesquita, 2010). In these games, protesters must perform a balancing act between creating enough publicity with some extreme actions without alienating the public.

Coups d’état

The same principles help us understand the strategic stakes in coups d’état. It is easy to think a coup’s outcome reflects the balance of power between the forces involved, especially military forces. Contrary to this, political scientist Naunihal Singh emphasised in his book Seizing Power (2014) that coups are coordination games. From his close study of 7 military coup attempts in Ghana between 1967 and 1981, he noted that most often nobody wanted to fight and the different forces wanted to side with whoever they thought everyone would eventually side with, regardless of their private preferences for the regime or rebels.

Consequently, information plays a key role in coups:

We would expect a coup to be won by the side that is best at manipulating information and expectations, which is not necessarily the side with the most brute force or popularity - Singh (2014)

Two famous examples of failed coups illustrate this. The first is the failed “1961 putsch of the generals” in 1961 in France. French army generals in Algeria, opposed to Algerian independence, rebelled and planned to land in mainland France. They had, by far, the best military units. The famously rambunctious President de Gaulle refused to step down. Instead, he gave a defiant TV speech:

I forbid all soldiers to obey the rebels… I shall maintain the legitimate power whatever happens, up to the term of my mandate or until such time as I cease to have necessary means to do so or cease to be alive… in the name of France I command that all means—I repeat all means—be used to bar the way to those men. Françaises, Français Help Me! - de Gaulle

The rallying of trade unions, political parties and conscripts to de Gaulle’s authority left the putschists isolated. Their unity shattered and the coup fizzled.

The other example is the 1991 attempt to oust Gorbachev and halt his reforms seen as threatening to end the USSR. The coup seemed guaranteed to succeed as its perpetrators controlled the entire state apparatus, including the army and KGB. But while they isolated Gorbachev in his villa, their mistake was underestimating the importance of communication (perhaps because their position seemed so strong) and leaving Yeltsin, the new President of the Soviet Republic of Russia, free to communicate.

This led to famous images of Yeltsin atop a tank amid anti-coup protesters. The coup leaders' unity collapsed as the population was emboldened and the putschists' public communication faltered. By the fourth day, it was over.

The coordination game played in a coup also gives another possible function to public protests: they can help coordinate elites to rally against the incoming regime.

Popular protests act as a public signal which facilitates the coordination among regime elites who are contemplating a coup. This means that elites use the size of popular protests to update their belief regarding the likelihood of coup success. - Casper and Tyson (2014)

Thus, one strategy for elite groups seeking to gain or retain power can be to leverage or even encourage public protests to rally other elite groups. This perspective helps make sense of one of the most important events in recent US history: the January 6 insurrection. Neither the protest itself nor the invasion of the Capitol would credibly lead to an alteration of the transfer of power on their own. Instead, Donald Trump explicitly encouraged the Capitol-bound protest as a way to sway Congressional support away from affirming Biden's presidency.

We're going to walk down Pennsylvania Avenue [...] and we're going to the Capitol, and we're going to try and give [...] our Republicans, the weak ones, because the strong ones don't need any of our help, we're going to try and give them the kind of pride and boldness that they need to take back our country. - Trump (January 6 2020 speech)

Propaganda

Finally, the importance of common knowledge and coordination games in determining regime support helps explain the nature of authoritarian propaganda.

Propaganda is often seen as brainwashing and quite effective. Countering this, cognitive scientist Hugo Mercier stressed in his 2020 book Not Born Yesterday that people aren't that gullible and propaganda often fails to persuade. As an illustration, he quotes a Nazi intelligence agency note: “Our propaganda encounters rejection everywhere among the population because it is regarded as wrong and lying.”

Instead of brainwashing, one of the main functions of propaganda may be to limit common knowledge of dissent. An experiment, run by my former student Greg Levy, supports this view. It featured a game where participants playing “citizens” could gain from coordinating dissent against a “dictator”. Across many games, the dictators were willing to pay substantial amounts of money to reduce the shared knowledge among citizens about a message inviting them to dissent. The dictators recognised the strategic value of shared knowledge, and they were right. When citizens had higher levels of shared knowledge, they were much more likely to successfully coordinate on dissent.4

In authoritarian regimes, propaganda may be a tool to limit the common knowledge of dissent among citizens. One way in which it fulfils that role is by monopolising the public space. It produces the only common knowledge available about the regime. With such a monopoly, paradoxically, even extreme, unrealistic claims can signal strength:

The very absurdity of the propaganda signals the regime’s strength to potential dissidents. It shows its capacity to force people to repeat nonsense. - Guriev and Treisman (2023)

Even if people know the propaganda is false, it may confuse them about the truth and what others believe. This can hinder coordination on dissent (Edmond, 2013).

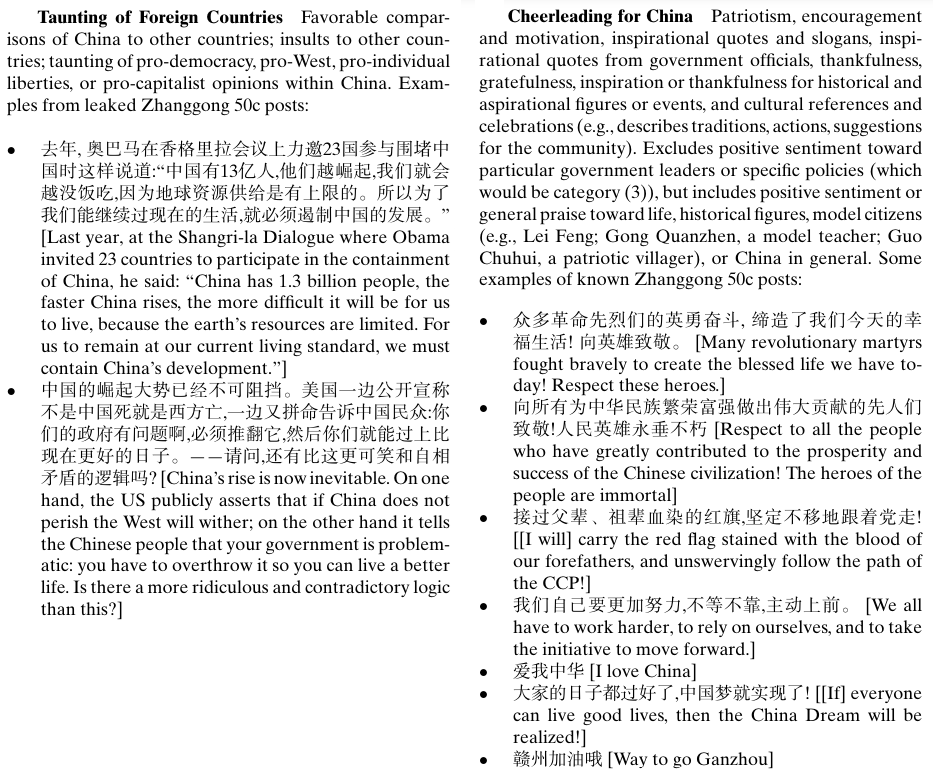

In the digital age, China has seemingly adopted a new strategy to undermine coordination on dissent. Critics have been allowed online to some degree (though this may be changing). What was stopped were critiques that could spur collective action. But the regime didn't just tolerate criticism, it actively mitigated its impact. In the social media era, the regime allegedly hired 2 million to flood online discussions with seemingly genuine pro-regime posts. Political scientists Gary King, Jennifer Pan and Margaret Roberts analysed 43,000 posts from a leaked archive of the Zhanggong Internet Propaganda Office. They estimate 448 million such posts are generated yearly.

Most surprising was the nature of these posts. Rather than fiercely defending the regime in bitter arguments with critics, the manufactured posts simply express positive regime support and steer discussion elsewhere. A possible conclusion is that the Communist regime accepts common knowledge of grievances but undermines common knowledge of collective action potential. Online complainers about the regime are met not by fierce opponents, but by users seemingly uninterested in doing anything.

Human politics can seem strange with its public ceremonies, nonsensical propaganda and extreme acts of dissent. But many of these features make sense when we understand the challenge and importance of coordination in collective actions. Common knowledge has a strategic importance when trying to either facilitate or prevent coordination. This fact generates political communication strategies where what is said is not the only thing—and sometimes not even the main thing—that matters. In addition to what is said, the way things are said plays a critical role in shaping what becomes common knowledge and what doesn’t.

References

Allport, F.H., 1924. Social Psychology. Boston, Houghton.

Binmore, K.G., 1994. Playing fair: game theory and the social contract (Vol. 1). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Casper, B.A. and Tyson, S.A., 2014. Popular Protest and Elite Coordination in a Coup d’état. The Journal of Politics, 76(2), pp.548-564.

Chwe, M.S.Y., 2013. Rational ritual: Culture, coordination, and common knowledge. Princeton University Press.

De La Boétie, É., 1580. Discourse on voluntary servitude.

De Mesquita, E.B., 2010. Regime change and revolutionary entrepreneurs. American Political Science Review, 104(3), pp.446-466.

Edmond, C., 2013. Information manipulation, coordination, and regime change. Review of Economic Studies, 80(4), pp.1422-1458.

Geanakoplos, J., 1992. Common knowledge. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 6(4), pp.53-82.

Guriev, S, Treisman, D., 2023. Spin dictators: The changing face of tyranny in the 21st century. Princeton University Press

Hardin, R., 1997. One for all: The logic of group conflict. Princeton University Press.

Hoffman, M. and Yoeli, E., 2022. Hidden games: the surprising power of game theory to explain irrational human behaviour. Hachette UK.

Hobbes, T., 1680. Behemoth or the long parliament. University of Chicago Press.

Hume, D., 1739. A Treatise of Human Nature.

Hume, D., 1741. Of the First Principles of Government

King, G., Pan, J. and Roberts, M.E., 2017. How the Chinese government fabricates social media posts for strategic distraction, not engaged argument. American Political Science Review, 111(3), pp.484-501.

Kuran, T., 1989. Sparks and prairie fires: A theory of unanticipated political revolution. Public Choice, 61(1), pp.41-74.

Singh, N., 2014. Seizing power: The strategic logic of military coups. JHU Press.

Zubok, V.M., 2021. Collapse: the fall of the Soviet Union. Yale University Press.

We have already seen Michael Chwe for his other book on the game theory in Jane Austen’s novels.

See the discussions in Binmore (1994) and Hardin (1996) on this point.

I include in the picture the inauguration of Charles III, as he is the Head of State of the UK. While he is not elected, the UK is a parliamentary democracy, and his role as Head of State would not persist without the support of the population. Polls regularly find large support for the monarchy in Britain. The absence of an election in Britain may make the inauguration ceremony all the more important to publicly legitimise the new Head of State. As stated by the BBC, "the Coronation may play a crucial role in the Royal Family's struggle to stay relevant."

I use here the term “shared knowledge” as the experiment featured several levels of higher-order beliefs, up to full common knowledge.

I was once at a talk by Barry O'Neal (UCLA Polisci) at IAS Princeton, and Eric Maskin was in the audience. Eric had just won the economics Nobel. Barry asked him whether he would be just as pleased if he had won secretly, with no public announcement. Eric said no of course not. The Barry asked: what if everyone knew privately but didn't know that anyone else knew. Again Eric thought this would be less satisfying.

I think common knowledge is important in the bestowing of honor. This is a bit more subtle, a bit harder to understand, than fear. It seems to matter to us that it is commonly known that we were honored.