The game theory of seduction and marriage... with Jane Austen

The enduring success of her early 19th century novels are in large part due to their persistent relevance

A key theme of this Substack is that seemingly irrational behaviour makes a lot of sense when we appreciate the right degree of complexity that people face when making decisions. In this post, I look at a domain where rationality is often deemed to be absent: love and seduction. I discuss this theme through the contribution of one of the most insightful writers on this topic: Jane Austen.

Finding a romantic partner is one of the things that can motivate us to spend tremendous time, effort, and thought. We can feel that the stakes are very high. What is said, what is suggested, and what is possibly thought by the other person acquires high importance. Talented writers capture the tension of these moments, the careful way people navigate these situations potentially fraught with missteps, missed opportunities or overly candid overtures. The persistent fame of Jane Austen, who wrote about such situations in the early 19th century, is a reflection of her talent to understand the rich layers of these situations.

This post is more than slightly inspired by the book by UCLA political scientist Michael Chwe, Jane Austen Game Theorist (2013). Chwe methodically unpacks Jane Austen’s six novels showing how her insights about human psychology in romantic situations can be related to many concepts from game theory.1

The high stakes of marriage in Austen’s novels

The economic considerations of Austen’s heroines are easily overlooked nowadays. The economist Thomas Piketty provided some background to the magnitude of the stakes they faced. The most striking change in fate is in Pride and Prejudice, Austen's most famous novel: without marriage, Elizabeth would face social demotion. Being unable to inherit her father’s estate with her sisters, she would inherit from her mother 1,000 pounds, which would provide her with an income of around 40 pounds per year, just around the average income of the day.2 In contrast, Mr. Darcy, who proposes to her, has an income of 10,000 pounds per year, representing 300 times the average income of the day! For comparison, the average annual income is around $30,000 in the US. The modern equivalent of Darcy would be earning 9 million dollars a year.

Austen’s clear-minded heroines are mindful of these stakes. When Elizabeth’s sister asks her, “Will you tell me how long you have loved him?” Elizabeth playfully answers: “It has been coming on so gradually, that I hardly know when it began. But I believe I must date it from my first seeing of his beautiful grounds at Pemberley.”

The stakes are higher for women

In addition to their pursuers’ wealth, Austen’s heroines also need to be very mindful of their characters. It is a truth (almost) universally acknowledged that single men tend to be more eager to secure a new partner than single women do. In short, women face a larger number of possible pursuers and should choose carefully among them if they are looking for a long-term partner.

In 1972, the biologist Robert Trivers explained this pattern with his critical contribution to our understanding of behaviours between men and women: parental investment theory. Making offspring is a long process requiring parental investment. However, the investments are not identical. Women, who carry a child for nine months, have to make a large physiological investment to start with. As a consequence, they are at risk of being taken advantage of by opportunistic men interested in a short-term relationship, but uncommitted to the long-term prospect of investing in building a family and raising children later on.

It is therefore perfectly rational for women to be extremely careful in their choice of partner and not to be too quick to accept the advances of a given pursuer. This issue is at the heart of Austen’s novels where heroines often have to avoid the deceiving appeal of men who seem charming but who are actually not of good character and not committed to a long-term relationship.

In that context, one has to appreciate the consequential decisions women have to make in Jane Austen’s novels. Unlike in the modern dating process, they cannot get to know a potential partner intimately before deciding whether or not to commit to a relationship. They have to appraise the traits of potential pursuers carefully from the limited interactions and exchanges they have with them. Jane Austen’s stories recount women who use their wit and determination to navigate these high-stakes situations, avoid the dangerous matches and manage to attract the right ones.

In many ways, Austen’s world is vastly different from ours. It would be easy to dismiss these novels as irrelevant to understanding seduction and romantic situations in our times. However, despite these differences, these novels still resonate with us today because they exposed, in a magnified way, an underlying logic of interaction between men and women that still exists.

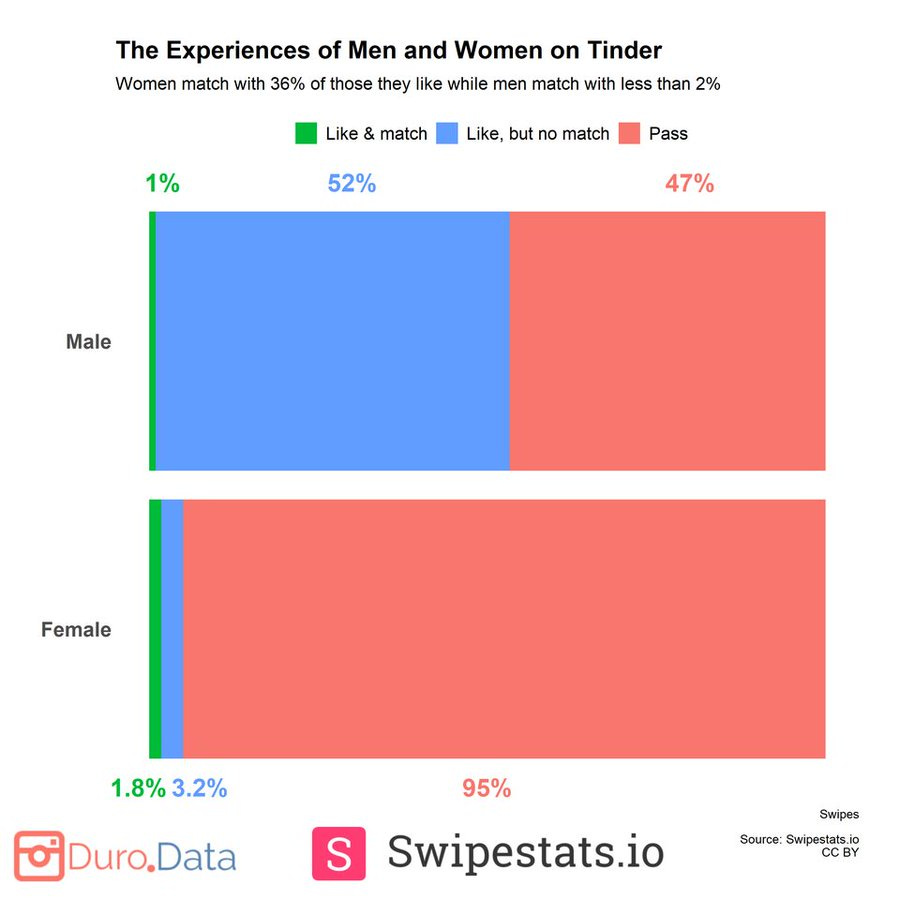

Even if times have changed, Trivers’ insights remain valid. The data now available from online dating platforms is unequivocal. Tinder data shows that men like 10 times more profiles than women do and that 1 in 50 of their likes leads to a match versus 2 out of 5 for women.3 Faced with many men happy to date them, women have to identify the ones who may be willing to invest in a long-term relationship. The costs of making wrong decisions are not negligible. Women looking for a long-term partner can lose precious years of their lives with men who are not truly interested in committing to a long-term relationship.

In the game of dating, this logic leads to an equilibrium where men must signal their genuine interest in a long-term relationship by investing time and resources in the dating process (Sozou and Seymour, 2005). This courtship behaviour makes it harder for men to pursue several women simultaneously. A man who chooses to court you, therefore reveals that you are high in his preferences.4

While a long phase of courtship before marriage has mostly disappeared in Western countries, asymmetric norms in the dating process nonetheless persist. In a survey conducted in 2015 in North America, 69% of the respondents stated that the man should pay for the first date, 87% stated that he should bring flowers then, and 66% stated that he should also pay for the second date (Cameron and Curry 2020). If these rules persist despite much greater equality between men and women, it is because they are the solution to the asymmetry in eagerness for short-term relationships between men and women.

Navigating the complex web of beliefs and intentions

In her writing, Austen offers clear insight into the stressful process of interacting with a potential partner to progressively reach a common understanding and eventually form a match. To be successful, one needs to be particularly adept at understanding others’ intentions and beliefs, a quality that Austen describes as penetration, which she states women are particularly gifted at.

One way to conceptualise penetration using game theory is as the ability to form accurate higher-order beliefs, beliefs about others’ beliefs. While a first-order belief might be “Ann thinks that Bob is charming,” a second-order belief could be “Bob believes Ann thinks he is charming.” A third-order belief might be “Ann thinks Bob believes that she thinks he is charming,” and so on.

Forming higher-order beliefs is challenging. Psychologists refer to the ability to put oneself in another's shoes as theory of mind. Getting an idea about the beliefs of another person—a second-order belief—requires us to simulate in our minds what beliefs would reasonably be formed from another person's perspective. Understanding other people’s beliefs about our beliefs—a third-order belief—requires simulating the perspective of somebody simulating our perspective. Climbing higher-order beliefs necessitates engaging recursively in this perspective-taking.5

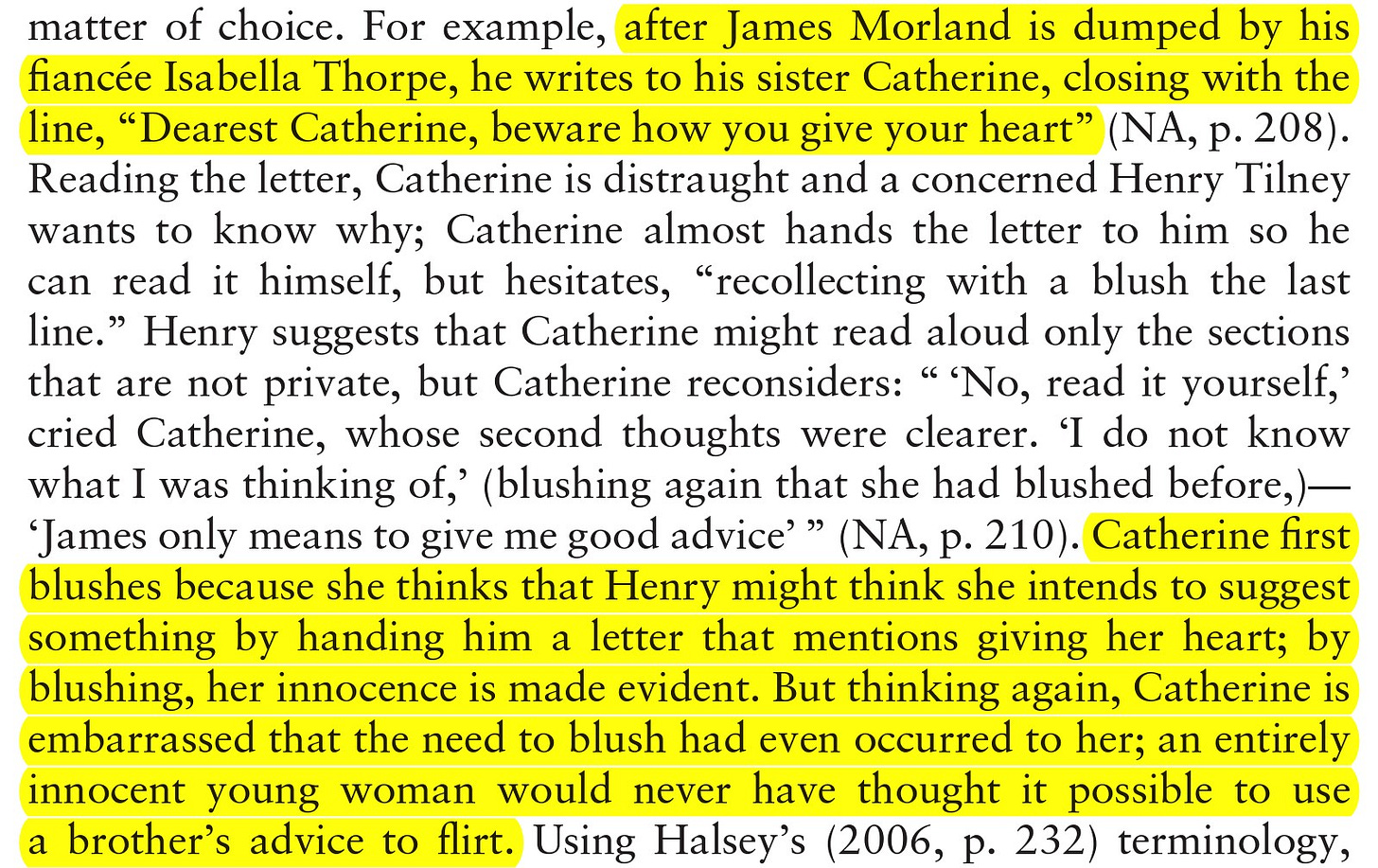

The literature in behavioural economics indicates that most often, people do not go much beyond third-order beliefs, as it becomes increasingly difficult to think clearly about higher levels. However, the situations in which we are considering finding a partner are among the most significant we face in our lives, and we can invest a considerable amount of cognitive effort and time to make sense of higher-order beliefs. In his book, Chwe presents an exemplary case where two characters—Catherine Morland and Henry Tilney in Northanger Abbey—are in a situation in which their understanding involves many more higher-order beliefs.

The situation is subtle, but we fairly easily understand it. The figure below decomposes the layers of higher-order beliefs; it shows that there are up to 8 of them!

One of Jane Austen’s talents lies in her ability to guide the reader through the considerations of higher-order beliefs that lie in the background of spoken interactions. Although the scenes described by Austen and the rules of interaction her characters follow differ significantly from our modern context, the underlying concerns they have for each other's intentions and beliefs remain relevant in today's interactions. Austen's novels continue to resonate because they allow readers to appreciate the anxieties and hopes associated with the uncertainty of these beliefs—emotions that are universally experienced by individuals with a romantic interest in someone else, even in contemporary times.

Taking measured risks in revealing one’s feelings

These higher-order beliefs matter greatly when individuals who meet in a non-romantic capacity explore the possibility of a romantic interest. In such situations, guarded overtures are cautiously made, trying to maintain a balance between suggesting a possible interest and retaining plausible deniability. Overtures are needed to gauge whether the interest could be reciprocal. Keeping an overture somewhat ambiguous allows for the pretence that nothing was intended beyond the facade of the interaction if it is not met positively. If an overture is met positively, another can be made.

As such overtures are exchanged, both individuals may progressively reach a shared understanding that the civil facade of the interaction may conceal a romantic interest on both parts. This process continues until the point where the remaining uncertainty is light enough for the facade to be lifted and one of the individuals to make an explicit overture. In the time of Jane Austen, this was suitably resolved by an engagement whereby the man proposes.

Proceeding carefully through a series of guarded overtures allows the progressive lifting of uncertainty. A key aspect to consider is how quickly to make overtures and whether to be more or less clear about one's eagerness. The courtship equilibrium described above requires the man to show the most eagerness as a signal of his romantic interest. However, there is a risk of women being too aloof and ending up unmatched later in their lives (with potentially dire economic consequences at the time). In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth and her friend Charlotte discuss this important point in the game of seduction:

Charlotte: It is sometimes a disadvantage to be so very guarded. If a woman conceals her affection with the same skill from the object of it, she may lose the opportunity of fixing him … In nine cases out of ten a women had better show more affection than she feels.

Elizabeth: … If a woman is partial to a man, and does not endeavour to conceal it, he must find it out.

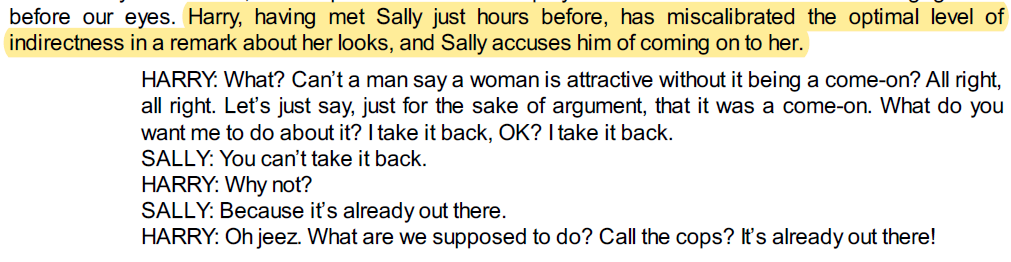

Here again, modern dating may seem very far removed from these considerations, yet this underlying logic still influences contemporary romantic interactions. Signalling too little interest might result in missed opportunities, but excessive eagerness could prematurely resolve uncertainty in situations where expectations about the prospect of a relationship are actually not aligned. When one’s feelings are not definitely set, suggesting eagerness might unduly heighten the other person’s expectations, necessitating a tedious toning down of these expectations later on. Conversely, if the other person happens not to be that inclined, revealing too much eagerness may lead to a painful explicit rejection. Both situations would lead to awkwardness because once uncertainty has been lifted and explicit statements have been made, they cannot be put back in the bottle.

The psychologist Steven Pinker (2007) describes such a situation occurring in the classic rom-com movie When Harry Met Sally (1989). Pinker points out that the effect of a too-explicit statement by Harry is to resolve the uncertainty about all the higher-order beliefs. The romantic interest of Harry is now common knowledge, that is Sally knows about it, Harry knows that Sally knows, Sally knows that Harry knows that Sally knows, and so on.

An important advantage of ambiguous overtures is that they maintain uncertainty about these higher-order beliefs and can help retain plausible deniability. When an ambiguous overture is made and rejected, both persons can pretend that nothing happened. They can continue with the facade of non-romantic interactions, even though they may have a good understanding of what happened. However, when a too-explicit overture makes the intention of one person common knowledge, there is no walking back. It is “out there”.

Jane Austen’s novels describe many situations where the facade of interaction is formally maintained by avoiding explicit statements, while those involved wittily retort to each other in ways that leave little actual ambiguity regarding their respective views (amicable or unamicable) of each other. Today, as then, this management of ambiguity and the progressive resolution of uncertainty is a key aspect of interactions fraught with possible romantic interests.6

The rules of courtship have noticeably changed in 200 years, but the underlying logic of strategic interaction in that process still follows many of the same principles. Jane Austen was a master at understanding the strategic layers of romantic situations and the psychology of protagonists involved in these interactions. It is because of the persistent commonality between the situations she describes and those we face today that Jane Austen still captivates modern audiences. Game theory helps us see her astute understanding of the layers of complexity in human interactions when a woman and a man have potentially romantic interests in each other.

References

Cameron, J.J. and Curry, E., 2020. Gender roles and date context in hypothetical scripts for a woman and a man on a first date in the twenty-first century. Sex Roles, 82(5-6), pp.345-362.

Chwe, M.S.Y., 2014. Jane Austen, game theorist. Princeton University Press.

Dekel, E. and Siniscalchi, M., 2015. Epistemic game theory. In Handbook of Game Theory with Economic Applications (Vol. 4, pp. 619-702). Elsevier.

Page, L., 2022. Optimally irrational: The good reasons we behave the way we do. Cambridge University Press.

Piketty, T., 2020. Capital and ideology. Harvard University Press.

Pinker, S., 2007. The stuff of thought: Language as a window into human nature. Penguin.

Sozou, P.D. and Seymour, R.M., 2005. Costly but worthless gifts facilitate courtship. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272(1575), pp.1877-1884.

Tomasello, M., 2019. Becoming human: A theory of ontogeny. Harvard University Press.

Trivers, R.L., 1972. Parental investment and sexual selection. In Sexual selection and the descent of man (pp. 136-179). Routledge.

Michael Chwe argues that Jane Austen is truly a game theorist aiming to propose a theory of strategy in human behaviour. I do not share this maximalist interpretation, but she clearly shows excellent and sensible insights that can be related to how game theorists study people’s interactions.

This information is provided by the markedly unlikeable character Mr. Collins who inelegantly points to Elizabeth's unenviable economic situation when proposing to her:

To fortune I am perfectly indifferent, and shall make no demand of that nature on your father, since I am well aware that it could not be complied with; and that one thousand pounds in the four per cents, which will not be yours till after your mother’s decease, is all that you may ever be entitled to. On that head, therefore, I shall be uniformly silent; and you may assure yourself that no ungenerous reproach shall ever pass my lips when we are married.

Steve Stewart-Williams has a recent post on men’s and women’s distributions of ratings on dating websites.

One aspect that made courtship costly was also its public nature at the time. An unmarried woman would meet potential pursuers in a somewhat social setting with other people (e.g., family, friends) present. The courtship process was therefore locally known, and a man could not have courted several women at the same time.

In modern times, internet dating in large cities has reduced this constraint and allowed people to date concurrently several possible partners in non-overlapping social circles. In reaction to this, Facebook groups “Are we dating the same guy?” have emerged allowing women to find out whether their date is also involved with other partners.

The psychologist Tomasello (2019) describes this process of perspective-taking as recursive inferences. It is certainly difficult computationally. However, the effort may be worth it in many situations as higher-order beliefs play a role in our strategic interactions (see Dekel and Siniscalchi, 2015, for a formal incorporation of these beliefs in game theory).

Some settings reduce the ambiguity about the state of mind of the persons involved. People involved in online dating, for instance, share the common knowledge that they are interested in looking for some type of romantic relationship. That leads to interaction dynamics that start from a fairly different point than in Jane Austen’s novels. However, the uncertainty remains about each person's specific interest in their date partner. The logic I described here still applies to this important aspect.

I cannot count the number of times a female was interested in me but I didn't recognize the signals. She was getting frustrated, I was baffled, I mean, I can't possibly be reading this right, right?

If I only knew then, what I know now.

This explains the crucible of expectations men experience as they attempt to get women’s attention. The problem is the much of the information women get from apps, and that women choose to prioritize, is irrelevant in selecting the best long term option. https://getbettersoon.substack.com/p/the-crucible-of-modern-dating-selection