The market failures of the marketplace of ideas

And how to address them

Following several posts discussing the reasons why our public debates do not live up to our expectations (here, here, and here), I am now looking at solutions. My last post made a reasoned case for free speech to ensure that all ideas have a chance to be heard in the marketplace of ideas. Unfortunately, even if all ideas can be heard, it does not mean that the marketplace of ideas necessarily selects the best ones. The marketplace of ideas can have “market failures”.

Taking the economics of ideas as goods seriously

The economic Nobel Prize winner Ronald Coase took the stance that the market of ideas should be studied like any other market. To follow this line of thought, let’s consider what type of good ideas are.

Asymmetry of information

Assessing the quality of ideas is hard. The typical consumer of newspaper articles, TV news programmes or blog posts does not have the expertise to confidently assess whether claims are aligned with empirical evidence. Suppose you read an article titled “Global warming is causing natural catastrophes”. Assessing whether this claim is well justified is not a trivial task.

While not fully experts in every area they discuss, journalists are likely more informed about the topics they cover than the general population. We therefore have a situation of asymmetric information, whereby the content producers have more information about the quality of what they sell than the consumers.

In that perspective, pieces of information and ideas/arguments sold on the marketplace of ideas can be thought of as credence goods: they are goods for which consumers need to trust the seller about their quality. Credence goods markets are everywhere. Think of car mechanics, doctors, or tutors for your children’s private lessons. You cannot be sure that the good you are getting is exactly what you expect to be paying for. Because consumers know less than the providers, these providers can abuse this trust and charge more or deliver lower quality.

Asymmetry of information is a cause of market failure because consumers may get ripped off, or they may decide not to buy the product altogether due to the fear of being ripped off. In the context of the marketplace of ideas, the asymmetry of information may allow the media to provide misleading information from time to time and it may lead people’s trust in them to decrease.

Externalities

Another characteristic of the exchange of ideas is that they have effects beyond the interaction between those directly exchanging the ideas. Other people in society may benefit from better ideas being exchanged. If you read a better source of information on vaccines, you may help me make better decisions, or I may copy your decisions that are likely to be better. So, from a social point of view, it makes sense to strive for better ideas to be exchanged in that marketplace of ideas. Economists call these indirect effects externalities. Commenting on this, Coase pointed out that these externalities are a likely source of market failures.

If we try to imagine the property rights system that would be required and the transactions that would have to be carried out to assure that anyone who propagated an idea or a proposal for reform received the value of the good it produced or had to pay compensation for the harm that resulted, it is easy to see that in practice there is likely to be a good deal of “market failure.” Situations of this kind usually lead economists to call for extensive government intervention. - Coase (1974)

Biases generated by the two sides of the market

Having pointed out these two characteristics of ideas, one can foresee likely market failures in the marketplace of ideas that may prevent it from leading to the best ideas being selected and exchanged.

Firstly, on the “supply side”, some providers of ideas and information may have non-economic motives. They may care less about addressing the demand of consumers for ideas than influencing them by selling them some specific views. Due to the asymmetry of information, consumers may not be able to discern this game of influence.

Secondly, on the “demand side”, consumers themselves are not after the truth but after convenient ideas and justifications. Even profit-maximising firms may be motivated to disseminate bad ideas and distorted content to address this demand. This is a problem, given that the individual consumption of bad information has negative social consequences (externalities).

Supply-side biases

Information can have value for some providers who aim to influence public opinion. As a consequence, actors who wish to influence public opinion may invest in the media market to sway consumers in convenient directions rather than inform them in their own interest.

Research has shown that supply-side slant can indeed have some effect on people’s views. A classic study on the effect of Fox News’ introduction in some parts of the United States in 2000 found that it significantly increased viewers’ likelihood to vote Republican (DellaVigna and Kaplan, 2007).

Billionaires in search of influence

Among highly wealthy individuals, some have an economic interest in influencing public opinion or a political preference to do so. Cases of billionaires acquiring large media corporations to influence the public debate have recurrently appeared in democratic countries: Berlusconi in Italy, Dassault and Bolloré in France, the Koch brothers in the US, Murdoch in the UK and Australia, and more recently Musk buying Twitter.

Several of these owners have an economic interest in shaping public opinion. Some of them are at the helm of companies that do business with governments, which respond to public opinion. This is the case for Dassault in France, who owns one of the largest defence companies in France and the conservative newspaper Le Figaro. Beyond such clear cases, any large company will have some interest in public opinion’s preferences over public policies, such as the regulation of their industry or the taxation of their activities.

Most people agree that we should not accept a medical journal owned by a Tobacco company as a credible scientific source. Similarly, we may doubt that the editorial stance of a news corporation owned by large industrial companies is fully independent from their companies’ economic interests. For that reason, it is reasonable to limit the ownership of media companies by industrial groups.1

Elite bias

Even without the concentration of media companies in a few wealthy hands, the cost involved in running large media platforms is so large that they are naturally owned by an economic elite, which can favour content aligned with their interest. One famous version of this criticism was made by Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky, who described mass media as “manufacturing” the consent of the public for the established economic and political order.

The mass media serve as a system for communicating messages and symbols to the general populace. It is their function to amuse, entertain, and inform, and to inculcate individuals with the values, beliefs, and codes of behavior that will integrate them into the institutional structures of the larger society. […] Money and power are able to filter out the news fit to print, marginalize dissent, and allow the government and dominant private interests to get their messages across to the public. - Herman and Chomsky (1988)

Without further qualification, this critique seems to rely on a view of economic and political elites as unified when shaping mass media as a “system” with a “function”. Instead, elites are composed of subgroups who often have competing interests and views. One insight from coalition game theory is that some elite groups can choose to ally themselves with disadvantaged groups to beat other elite groups.2 History is rife with such cases. Intra-elite competition may therefore make mass media less monolithic in their content than Herman and Chomsky suggested.3

Another possible critique is that the social group in charge of producing most of the mediatic content—journalists—may produce content that is biased towards their (upper-middle-class) worldview, independently of the ownership of the media. This criticism was made by the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu in his book on television (1996).

With their permanent access to public “Visibility, broad circulation, and mass diffusion”—an access that was completely unthinkable for any cultural producer until television came into the picture—these journalists can impose on the whole of society their vision of the world, their conception of problems, and their point of view. - Bourdieu (1996)

These critiques may seem less relevant today as large media companies face the grassroots competition of small broadcasters since the internet has dramatically reduced the cost of producing and distributing media content. This competition must have an effect on the ability of leading media to maintain questionable narratives unchallenged.4

We should, however, not dismiss these concerns as being outdated. The control of large media platforms still comes with a disproportionate ability to influence public opinion even if dissenting voices can be heard on the internet. It represents what the political scientist Robert Dahl called “inequalities in the distribution of political resources” (Dahl, 2000).

Foreign media

Another important type of influence seekers are foreign governments that may want to influence public opinion in other countries. In recent years, this has been the case with two autocratic regimes: Russia and China.

Russia's foreign channels, Russia Today and Sputnik, have been used to broadcast narratives aligned with the Russian regime abroad. In 2017, after denying these channels press access to his campaign, French President Macron stated in front of Putin: “Russia Today and Sputnik did not behave as media organisations and journalists, but as agencies of influence and propaganda, lying propaganda – no more, no less.”

When these channels were banned from Western countries in 2022, following the invasion of Ukraine, some complained it was against freedom of speech. However, the rules of freedom of speech are designed by a society for its own benefit, in particular the functioning of its marketplace of ideas. It seems reasonable to limit the participation of external actors who have antagonistic interests to that society and no inclination towards helping the best ideas to emerge there.

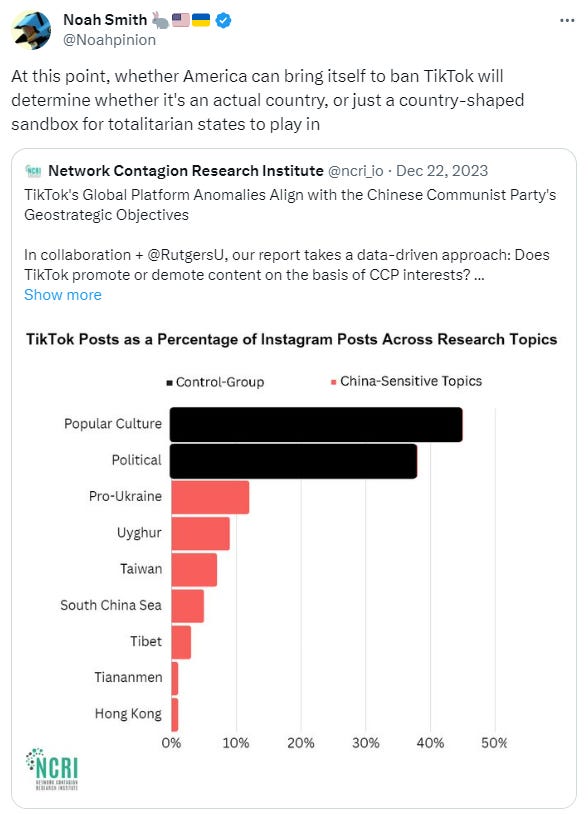

The highly influential video platform TikTok raises another, but similar, problem. It is not formally owned by the Chinese government, but the extent of the direct and indirect control of the Chinese communist party apparatus on Chinese firms is such that TikTok cannot be considered an actor independent from the Chinese government's interests. With its incredible reach in youth cohorts in the West—it is said to have 150 million users in the US alone5—it presents a substantial potential to influence public opinion in liberal democracies. Here again, it is reasonable to restrict the risk of the influence of a foreign autocratic regime on public opinion. This point was recently made by Noah Smith.

Demand-side biases

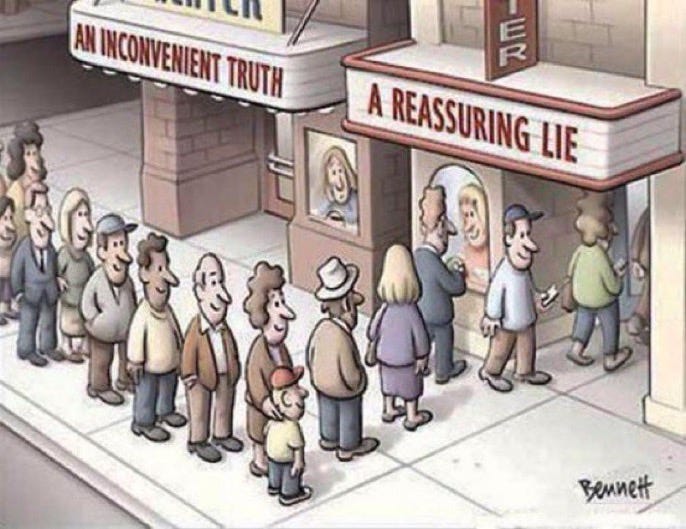

People are not looking for the best ideas

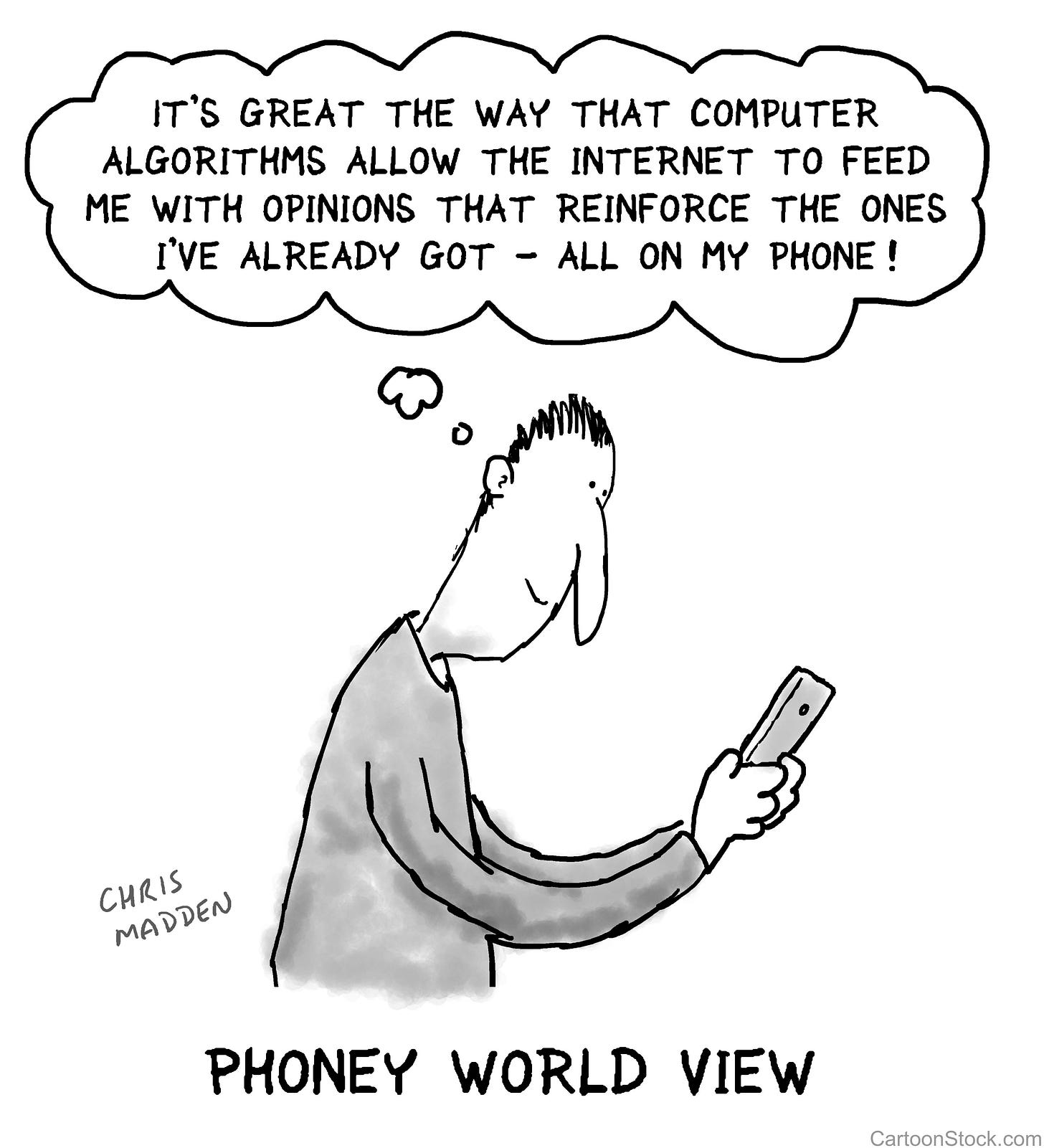

Even if barriers to entry and large actors with disproportionate influence are removed, the marketplace of ideas may predominantly work as a marketplace of rationalisations where people sort themselves into different informational corners. In these corners, they find providers of content that suit what they are looking for to uphold their beliefs and give them arguments in future debates.

The issue here is that it is the market mechanism itself that may lead to this outcome. The “selection of the best ideas” is a socially desirable outcome, not necessarily an individual one. It may therefore not emerge from the transactions in the marketplace. If consumers do not have a preference for the best ideas, but for the ideas that are most convenient to them instead, it is not clear why the marketplace of ideas would lead to the best ideas prevailing.

A justification for public good provision

Since the exchange of good ideas benefit society, they can be characterised as having a positive externality. Goods with positive externality are typically under-provisioned because consumers do not factor in the indirect social benefits in their personal choices. When a good with a positive externality is under-provisioned by the market, the solution is often for it to be provided as a public good by a publicly funded organisation. This perspective can therefore provide a justification for the existence of public providers of information funded by taxpayers: to provide citizens with content not strictly determined by market forces.6

Public media faces at least two limitations in this endeavour. First, to be relevant, it must be watched and therefore produce content that is to some extent competitive with privately owned media. A shop offering very healthy vegetables may struggle to sell anything when surrounded by chocolate and cookie shops. This issue is compounded in most countries—with the notable exception of the UK—by the fact that public broadcasting is partly paid for by advertising. It further drives public broadcasters to mimic the content of private ones.

The second limitation is that public broadcasting often fails to be politically neutral. In autocratic countries, public media understandably toe the government’s line. But in democratic countries, public media also seem to display political slants. Specifically, they tend to be on the left. This is, for instance, how public broadcasters in a range of English-speaking countries are classified in terms of political slant.

If you share that political stance, you may be tempted to answer that these positions are right and hence should be shaping the content of a public broadcaster. However, the slants here are perhaps not so much about factual reports that can be right or wrong—like whether climate change is real and man-made. Instead, they are often about social values and preferences. My impression is that these slants are more pronounced over cultural issues than economic ones.

A politically neutral public broadcaster can provide a public good by being trusted across partisan lines. By maintaining a neutral stance, a public broadcaster can earn the role of a respected adjudicator by all sides when discussing contentious topics. Doing so, it is possible that it would limit biases in other media by contributing to establish norms of good reporting of news and arguments. The high reputation of the BBC—which shows the least slant in the above figure—in terms of quality of reporting speaks to this possible role. It is one of the most trusted sources of news in the UK across the political spectrum.

Another possible role for public broadcasting is to offer a platform to minority views that are not provided by private actors in the marketplace of ideas. These may be views that question the consensus and raise questions that are being overlooked by the majority. Discussing Mill’s views on the marketplace of ideas, Gordon (1997) stated:

It is the [opinion] which happens at the particular time and place to be in a minority" that ought to be countenanced, the opinion "which, for the time being, represents the neglected interests, the side of human well-being which is in danger of obtaining less than its share. - Gordon (1997)

Offering a platform to some views does not mean to endorse them but rather to give, from time to time, the opportunity for minority views to be heard. Most of them are likely going to be ignored, but some may get the opportunity to catch on if they are making points that are convincing to a substantial share of viewers. On French television, at the time of political elections, every party is given some equal airtime to advocate for their position. It is a time when you can hear the views of revolutionary Trotskyists, or the party of farmers and hunters on prime time slots. In Australia, SBS gives time to migrant minorities and indigenous cultural content. These are contents that a media market may fail to provide and for which there is a role for public media.

The metaphor of a marketplace of ideas is interesting to think of the benefits of a free public sphere but also of its limitations. A marketplace of ideas can have market failures leading to bad ideas prevailing over good ones. To limit supply-side biases, restricting the market concentration of providers, and regulating their conflict of interest are reasonable approaches. To cater for demand-side biases, providing non-partisan information and views as a public good also seems a good solution.

One limitation of this post’s discussion is that it has been focused on the mass media, which are being challenged by the growing role of the internet. By decentralising the production of content, the internet may be progressively making the above concerns less relevant. Not only are people able to access a greater array of content on the internet than in the TV-newspaper media sphere of the 20th century, but the competition from these new actors drives mainstream media to adapt their content to stay competitive.

The issues raised by demand-side biases are therefore exacerbated by the rise of the internet. Likely as a consequence, the criticism of the public sphere as being manipulated in a top-down way by media corporations has lost some of its importance, while greater attention is now given to bottom-up risks of “misinformation” being generated via echo chambers and politically motivated users on the internet.

This is the second post in a series of three posts on how to improve the marketplace of ideas. My next piece will focus on how to tweak the incentives of content producers on the internet to correct these risks of demand-side biases.

References

Bourdieu, P., 1998 (1996 original edition). On Television. New York: New Press.

Coase, R.H., 1974. The market for goods and the market for ideas. The American Economic Review, 64(2), pp.384-391.

Dahl, R.A., 1989. Democracy and its critics. Yale University Press.

Dahl, R.A., 2000. On democracy. Yale University Press.

DellaVigna, S. and Kaplan, E., 2007. The Fox News effect: Media bias and voting. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), pp.1187-1234.

Gordon, J., 1997. John Stuart Mill and the" Marketplace of Ideas". Social theory and practice, 23(2), pp.235-249.

Haidt, J. and Lukianoff, G., 2018. The coddling of the American mind: How good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure. Penguin UK.

Qian, R. and Wu Y.,,2023. Whither Journalism? The Impact of Social Media on News Production in China. Working paper

Even in the case of Elon Musk—who has professed a public defence of freedom of speech on his platform—the economic interests of his company Tesla are heavily influenced not only by the US government but also by the Chinese government. This represents a risk of conflict of interest when designing the Twitter algorithm which orders content on the platform.

Large media holdings or social networks in the hands of single wealthy owners also raise questions about the “competitive” nature of the marketplace for ideas. Limiting the ownership concentration of media corporations is worth considering from that perspective.

One important insight from game theory is that coalitions can be unstable and change in very flexible ways. The right-left dimension is often seen as reflecting the fact that richer people have an interest in supporting low redistribution (right) while poorer people have an interest in supporting more redistribution. But a social group with advantaged members may also benefit from allying itself with some disadvantaged social group when competing with another advantaged social group. I’ll discuss this important insight from coalitional game theory in a future post.

Criticising the view of a single economic elite controlling power in society in a top-down manner, the political scientist Robert Dahl proposed instead to describe Western “liberal democracies” as polyarchies, where power is spread among competing groups and organisations, without one elite group monopolising power and shaping society’s institutions in a top-down way (Dahl, 1989).

A recent study looking at the early penetration of the social network Weibo in China supports this idea. This introduction “decreased newspapers’ production of politically biased content while prompting them to produce more investigative reports” (Qian and Wu, 2023).

Source: https://backlinko.com/tiktok-users

If one takes the example of court trials, the aim of which is to identify the truth, accusers and defendants can hire private investigators and lawyers who will present the best case for them. However, in addition, public services, like the police, will provide information in a neutral way, aiming to show no bias towards either party.

Want a secret technique to cut through all of these very valid complexities you note?

Weaponized "pedantry".

Not only can it cut through the initial problem, it also allows one to objectively identify the delusional among the *relatively* intelligent (which is a huge part of the problem: *our very best intellectuals are quite literally delusional*).

Granted, this is well beyond most neurotypicals, but luckily we have non-neurotypicals who can teach them.