What side are you on?

How coalitional thinking shapes our discussions

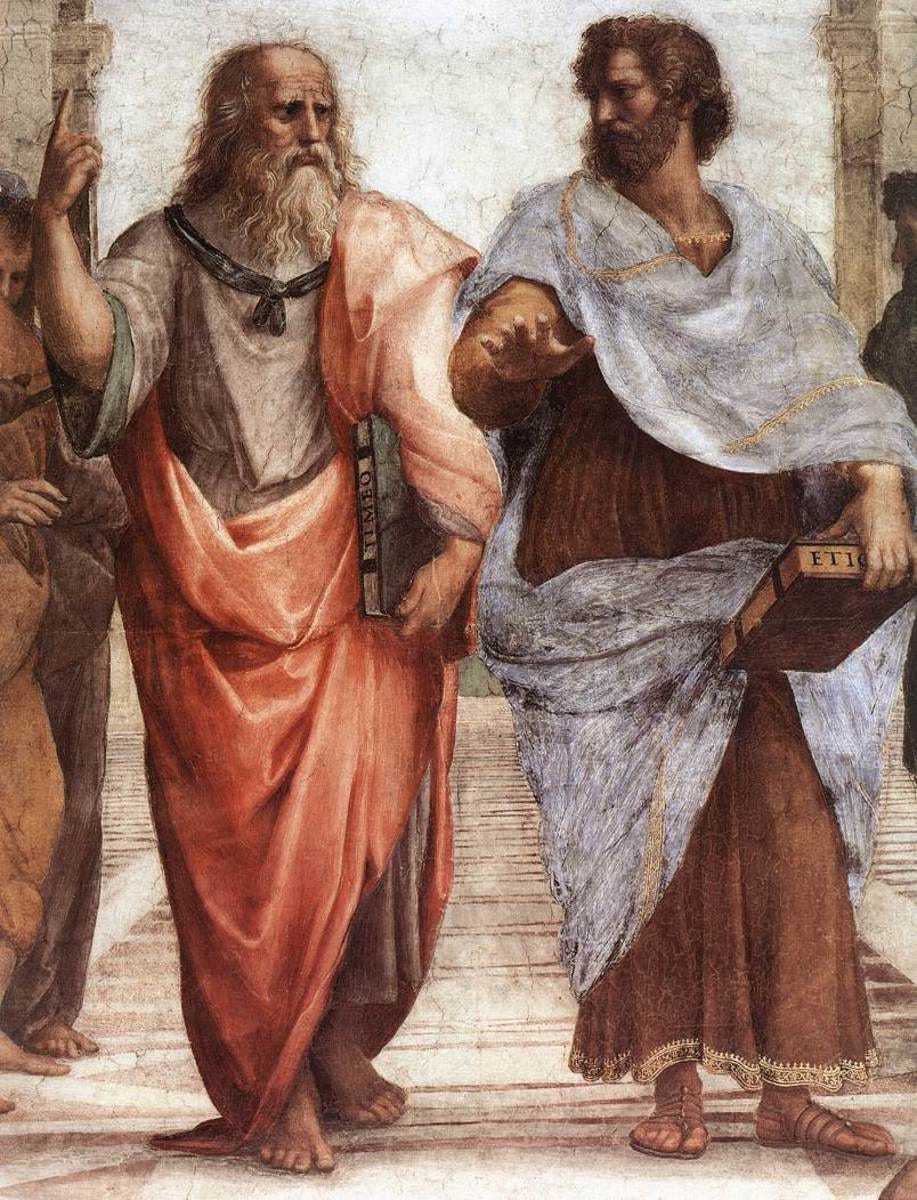

Rafael’s School of Athens fresco, completed in 1511 in the Vatican, is famous for representing Plato and Aristotle engaged in what seems to be an intellectual exchange. These two icons of wisdom appear to display calm and reason, pursuing the joint goal of finding the truth. In a way, it depicts an ideal of intellectual debate where ideas are assessed on their merit by all.

We often debate. From office politics around the coffee machine to proper politics on Twitter, we argue about our different views. Usually, the underlying assumption in this kind of exchange is that we use reasoning to reach a better common understanding. Reality, however, is often far from this ideal.

There is another underlying layer of interaction that often takes precedence over reasonable discussion to explain the dynamics of a discussion: coalitional thinking. Behind what appears to be an exchange of arguments and counterarguments, the key question we often ask our interlocutor is: What side are you on?

Who said that?

A while back somebody posted this citation below from Hayek to a libertarian page. The reaction was swift and angry. Posters did not appreciate the apparent misandry of the actress.

Except… it wasn't a quote from actress Salma Hayek, but from the free market economist Friedrich Hayek, famous to have inspired Margaret Thatcher. The quote, from his book The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism (1988), highlights F. Hayek's view that established institutions and traditions have been validated as effective ways to organize human activities. He argues that designing new institutions from scratch, say after a revolution, and expecting them to function effectively is a misconception.

Getting libertarians to disagree with this statement simply by changing its attribution to a Hollywood actress is undoubtedly funny. But it illustrates something more fundamental about how we make up our minds about political arguments. Our judgment of statements isn't solely based on their intrinsic merit. We also consider their origins and whether we perceive the speaker as a friend or a foe.1

Coalitional psychology

The anthropologist John Tooby passed away last week at the age of 71. With his wife Leda Cosmides, they founded one of the most influential schools in evolutionary psychology, integrating insights from cognitive sciences and game theory. Among their many contributions, one of them is the article “Groups in Mind: The Coalitional Roots of War and Morality” (2010). The key point made by Tooby and Cosmides in that article is that the ability to navigate coalitional politics was a crucial factor for success in our evolutionary history.

Theoretical considerations and a growing body of empirical evidence support the view that the human mind was equipped by evolution with a rich, multicomponent coalitional psychology. […]

Across human evolution, the fitness consequences of intergroup aggression (war), intimidation, and force-based power relations inside communities (politics), were large, especially when summed over coalitional interactions of all sizes. These selection pressures built our coalitional psychology, which expresses itself in war, politics, group psychology, and morality. - Tooby and Cosmides (2010)

Coalitions, as noted by anthropologist Pascal Boyer, permeate our social interactions and take various forms: “political parties, street gangs, office cliques, academic cabals, bands of close friends. They can include thousands or millions of individuals in ethnic or national coalitions” (Boyer, 2018). Success in social spheres often hinges on our ability to form and maintain coalitions. These considerations can often trump the search for truth. Better be wrong in a strong group than right alone.

Coalitional press secretaries

Coalitional psychology subtly yet significantly influences our engagement with ideas, often operating beyond the realm of our full awareness. In my last post, I described how we likely use our reasoning ability more as lawyers than as scientists: to win arguments rather than seek truth. In a recent article on how coalitional psychology influences our reasoning, Dan Williams (2023) further delves into this notion, proposing that in debates, we often play the role of press secretaries for our groups (e.g. political parties, religious groups). We do not engage in a dispassionate and rational assessment of ideas, rather we defend our team.

The theory does not just predict a correlation between partisan identities and beliefs; it predicts the direction of partisan bias […] partisans form factual assessments of things like the economy and crime rates that reflect favourably on their party; they inflate their party’s successes and rival parties’ failures; and they attribute responsibility and blame for good and bad political outcomes in characteristically partisan ways. - Williams (2023)

This press secretary mentality influences how we see arguments. We are inclined to view an argument as more credible if it aligns with our political beliefs, and less so if it contradicts them. In a meta-analysis including 51 experiments, Ditto et al. (2019) found that this “tendency to evaluate otherwise identical information more favourably when it supports one’s political beliefs or allegiances” is present both on the right and on the left.2

Moreover, our thresholds for accepting arguments vary depending on how they align with our group's views. We rigorously scrutinize arguments that clash with our beliefs, seeking counterarguments, while those in harmony with our views are often accepted with less critical examination. This phenomenon manifests as a selective demand for rigour.

Friend of foe? The key underlying question when judging arguments

Even more strikingly, the very same argument is judged differently depending on whom we attribute it to. In a psychological study, researchers asked people whether they agreed with several aphorisms (Hanel et al., 2018). To get an idea, here are three of these aphorisms with their source:

A gentle answer turns away wrath, but a harsh word stirs up anger – Prov 15:1

Do it or do not do it - you will regret both – Socrates

Abundance of knowledge does not teach men to be wise – Heraclitus

In a twist unbeknownst to participants, the sources of these aphorisms were randomly altered. The study revealed a striking pattern: when aphorisms were attributed to the Bible, Christians agreed more and atheists agreed less. Similarly, when the aphorisms were attributed to a politician, people from the same political side agreed more, and those on the other side agreed less.

Can we hope that scientists are not prone to such biases? Perhaps not. A recent study found the same result with economists. Mohsen Javdani and Ha-Joon Chang (2023) started by asking nearly 2,500 economists their views about how they should form their judgement when considering arguments. A large majority, 82%, answered that “a claim or argument should be rejected only on the basis of the substance of the argument itself.”

The researchers then investigated how economists actually formed their judgement about several statements. Similarly to the previous study, the “source” of the statement was randomly varied. It was either a mainstream economist (with widely accepted views in the profession) or a less/non-mainstream economist (more critical of popular views in the profession). Here are three excerpts of statements with their actual source:

“Academic economists, from their very open-mindedness, are apt to be carried off, unawares, by the bias of the community in which they live. […]” - Irving Fisher

“A realistic view of intellectual monopoly [e.g. patent, copyright] is that it is a disease rather than a cure. […]” - David Levine

“The market economy has depended for its own working not only on maximizing profits but also on many other activities, such as maintaining public security and supplying public services—some of which have taken people well beyond an economy driven only by profit. […]” - Amartya Sen

The study found that when the provided source was “mainstream”, economists were much more likely to support the statement than if they were told the source was not mainstream, or if they were not given any source at all.3

Even more striking than these different views on a given statement, the same effect has been found for visual images. In a telling experiment by Kahan et al. (2012) participants were asked to look at images of a protest and told that police had intervened to stop it. The researchers randomly varied the information provided about the protest: some participants were told it was an anti-abortion protest (right-wing), while others heard it was against a policy barring openly gay people from the military (left-wing). Participants were found to be more inclined to perceive the protestors as obstructive and threatening, thus justifying police action, if the protest opposed their political beliefs. While the saying goes “seeing is believing”, it seems that often “believing is seeing”.

Outside of politics, readers will certainly be familiar with the fact that this bias is on display in every stadium hosting sporting matches. Fans of opposing teams, watching the same game, often interpret on-field actions differently. This divergence is particularly noticeable when determining if a foul occurred.

Signalling allegiance

While group allegiances are often clear, they are also often ambiguous. Consider whether you can candidly discuss today's political issues with your friend Alice without wondering if she holds opposing views. In the workplace, can you confidently share criticism about Bob with Alan, or is Alan covertly aligned with Bob? Navigating these complexities of allegiance forms a crucial part of our social interactions.

Our coalitional psychology includes an alliance detection system, that is, a system that spontaneously attends to information about the social world that suggests a specific pattern of solidarity or affiliation between some individuals. - Boyer (2018)

In this quest to determine allegiances, those eager to join a group must demonstrate their loyalty. Merely expressing support for a group is an initial, albeit insufficient, step. A deeper question looms: Will this loyalty persist through challenges and adversity? This aspect of detecting loyalty and gauging potential betrayal is a critical dynamic within any coalition. According to Jonathan Haidt, it is a key part of our psychology:

The loyalty/betrayal foundation is just a part of our innate preparation for meeting the adaptive challenge of forming cohesive coalitions. - Haidt, 2012

The commitment to a group can be signalled by the willingness to bear entry costs. Examples include challenging initiation rituals like hazing in various institutions practised in many schools, teams, and fraternities. Another possibility is to increase one’s cost to exit the group. Getting a visible tattoo from a gang is not only a sign of allegiance, it also reduces one’s opportunities to join another gang or to find a normal job. It is a credible signal of commitment (Gambetta, 2009).

Recently, several authors have suggested that beliefs too can function as signals of commitment (Boyer, 2018; Mercier, 2020; Funkhouser, 2022; Williams 2023). Aligning one's beliefs with the group enhances others’ trust, while deviating from core group beliefs risks reputational damage. Others may wonder: If you don’t support that view the group is defending, what else are you not supporting?

In that perspective, radical (and even absurd) beliefs may be valuable as signals of allegiance. By being costly to advertise to people outside of the group, absurd beliefs credibly indicate your allegiance and future commitment. This signalling logic (not necessarily fully conscious) may explain why we often see absurd political statements on social media.4

How to really change people’s minds

The points above offer new perspectives on how people change their minds. Often, we rely on rational arguments to sway opinions, but this approach’s effectiveness may be limited due to our inherent coalitional psychology. Philosopher Erik Funkhouser (2022) suggests that several alternatives are de facto likely to be more effective:

Challenging the tribal affiliation: trying to peel off somebody from a group by getting that person to join another group instead. The incentives to hold the previous group’s beliefs will disappear.

Identifying in-group dissenters: pointing to people in the opposite group who agree with your position (e.g. a Republican who believes in climate change). It will indicate that the belief is not a requirement for group membership.

Denying that the belief reflects tribal values: fighting a given view from a group with other values held by the group. Such arguments are less likely to be seen as implying that a criticism of that view is against the group.

We often believe that in debates, we use reason and compelling arguments to persuade others. However, beneath the surface of these argumentative exchanges lies a layer of coalitional thinking. The pivotal question at this level is not about the strength of the arguments, but rather if the person we're engaging with aligns with our coalition. The likelihood of changing minds in such dialogues hinges significantly on how this perception of coalitional alignment is resolved. This understanding reveals that our discussions are not just about logical persuasion but also about identifying and navigating group affiliations.

This post is the third of a series of posts on the good reasons behind our wrong beliefs. The first one was on the gains from self-deception and overconfidence, the second one was on how we use reason to convince others. In the next post, I will discuss the emergence of a marketplace for justifications.

References

Boyer, P., 2018. Minds make societies: How cognition explains the world humans create. Yale University Press.

Cosmides, L. and Tooby, J., 2010. Groups in mind: The coalitional roots of war and morality. Human morality and sociality: Evolutionary and comparative perspectives.

Ditto, P.H., Liu, B.S., Clark, C.J., Wojcik, S.P., Chen, E.E., Grady, R.H., Celniker, J.B. and Zinger, J.F., 2019. At least bias is bipartisan: A meta-analytic comparison of partisan bias in liberals and conservatives. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(2), pp.273-291.

Funkhouser, E., 2022. A tribal mind: Beliefs that signal group identity or commitment. Mind & Language, 37(3), pp.444-464.

Gambetta, D., 2009. Codes of the underworld: How criminals communicate. Princeton University Press.

Haidt, J., 2012. The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Vintage.

Hanel, P.H., Wolfradt, U., Maio, G.R. and Manstead, A.S., 2018. The source attribution effect: Demonstrating pernicious disagreement between ideological groups on non-divisive aphorisms. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79, pp.51-63.

Hayek, F., 1988. The fatal conceit: The errors of socialism. University of Chicago Press.

Javdani, M. and Chang, H.J., 2023. Who said or what said? Estimating ideological bias in views among economists. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 47(2), pp.309-339.

Kahan, D.M., Hoffman, D.A., Braman, D., Evans, D. and Rachlinski, J.J., 2012. " They Saw a Protest": Cognitive Illiberalism and the Speechconduct Distinction. Stanford Law Review, pp.851-906.

Mäki, U., 2005. Models are experiments, experiments are models. Journal of Economic Methodology, 12(2), pp.303-315.

Morgan, M.S. and Morrison, M. eds., 1999. Models as mediators: Perspectives on natural and social science (No. 52). Cambridge University Press.

Page, L., 2022. Optimally irrational: The good reasons we behave the way we do. Cambridge University Press.

Rivlin, A.M., 1987. Economics and the political process. The American Economic Review, 77(1), pp.1-10.

Williams, D., 2022. Signalling, commitment, and strategic absurdities. Mind & Language, 37(5), pp.1011-1029.

Williams, D., 2023, The Case for Partisan Motivated Reasoning. Synthese, 202(89), pp. 1-27.

Arguably, the misattribution can be read as changing the meaning of the quote. From a criticism of the enticement of social planning (“what they imagine they can design”), the quote can be read as a criticism targeting men and not women.

One possible counter-argument is that people are Bayesian and use their prior beliefs (favourable to their political opinions) to judge new arguments. Hence they found arguments running against their prior beliefs less credible. I share Dan William’s (2023) assessment that coalitional psychology offers a better explanation of the empirical findings.

Edit: For the record, the Twitter account Crémieux has raised concerns about how this study was conducted.

One criticism is that people do not need to hold these beliefs to make such statements. One possible answer, from their perspective of my post on self-deception, is that it is easier to convince others that we have these beliefs if we believe in them to some degree.

![Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, [IMAGE] | EurekAlert! Science News Releases Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, [IMAGE] | EurekAlert! Science News Releases](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4_TW!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8cf9617f-8893-4e3e-9d0b-4b763c61e4a1_400x310.jpeg)

First of all, I want to say that this is a really good article! 👏 It explains something that we often observe in others (of course we see it more in others than in ourselves).

We tend to think that rationality and discussions are both meant to help us evaluate information based on its merit so we can find and adopt the best beliefs and arguments out there. But like you say, this is not what usually happens. Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber argue that reason evolved to create reasons (so we can justify our behavior to others) and to evaluate reasons (so we are not fooled by the reasons other people give to persuade us). They believe that when we discuss something, the first reasons we share are often weak and it is only when we are challenged that we try to come up with better reasons. Aside from the fact that this understanding of reason makes us seem a bit pathetic (in my opinion) and not as wise as we want to think we are, this interpretation also reveals a great opportunity to foster rationality: debates with people who disagree with us!

I've realized that when someone disagrees with me, I see it as a challenge and this forces me to make an effort: to try to find relevant information, express it clearly and persuasively, and to craft better arguments – more so than when I just think about that topic on my own. So I think that when two people disagree, they can challenge each other which can help them reason better. Of course, for this to happen many things must go right (people need to be somewhat rational, educated on the topic, and open to learning more or able to admit they may be wrong). But I think that, if we can focus more on the beliefs or topics discussed and leave the group identity behind, we can evaluate ideas on their merit (more than usual). If both people act like lawyers or press secretaries for their beliefs, they are determined to make the best case for them and that's what we want. But the other person will do the same. So then we then need to try to find the best information, perspective, or arguments presented - regardless of who shared them and which groups they belong to.

But of course, doing this takes effort and we need someone else to help us reason better. When we just assess information on our own, we don’t put in as much effort and we often rely on heuristics that save us time – at the expense of accuracy. In my opinion, judging a piece of information based on what the group thinks about it is not just about proving our allegiance, but about avoiding effort. If we like and trust our group, we assume that they know better than us, so we adopt the group’s beliefs and values (as long as they do not seem too irrational). It’s the same with people assuming that whatever an expert says, it must be true – it’s easier to trust them than to go and look for scientific studies and figure out what’s true or false. Plus, when we evaluate information, it’s much easier to think that whatever is familiar and makes intuitive sense is true, and we’re likely to be more familiar with the beliefs and arguments shared by someone in our group or someone we already like and trust.

I think that *good* debates are very valuable – they give us the chance to think deeply about what we think and why we think that and to refine our beliefs and arguments. I just wish we had more opportunities to practice this. What we see and experience on social media is almost always the opposite of this (in my opinion). Anyway, this was my contribution to the topic; maybe you or someone else will find this interesting.

The Hayek trick relies on the ambiguity of the word "men", which changes its meaning depending on whether it's used by a man last century or a woman today.