Friendship politics

Everything you have always wanted to know about friendship

We are now reaching the end of my series of posts on coalitional psychology and game theory. This post is part of a short three-part series on how coalitional dynamics shed light on many aspects of our social life. This post is about friendship.

The importance and value of friendship are stressed in the Bible1 with these words:

A faithful friend is a strong defence: and he that hath found him, hath found a treasure. Nothing can be compared to a faithful friend, and no weight of gold and silver is able to countervail the goodness of his fidelity. — Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) 6:14, Douay-Rheims Bible

Friendship is about positive feelings and the willingness to support each other. So why is it sometimes hard and stressful to navigate our positions in groups of friends? The fact that managing friendships can lead to anxiety is represented in Pixar’s Inside Out 2, when Riley chooses to leave her original group of friends to join the cool girls from the hockey team.

The political calculus of friendship groups

It might seem uncouth to talk about political calculus in friendship groups. However, a purely idealist vision of friendship cannot explain the dynamics and tensions that exist within groups of friends.

Choosing one’s friends

The mystery of friendship?

At the start of any friendship, there is a choice: deciding to be friends with some people rather than others. These choices are clearly not random. We are selective about the friends we make.

An intuitive explanation of friendship is that people bond because they share similar tastes and therefore like to do things together. Tastes do matter when choosing friends, but it is not clear that they are the fundamental driver of friendship. Indeed, when people appear to have similar tastes to their friends, it is often because they choose to adapt their tastes to them. Fashion preferences are a good example: people often adapt how they dress to fit in with the group of friends they want to join.

The strategic importance of choosing the right partners

So what’s going on? We can answer this question by starting from the underlying reality of friendship groups: they are coalitions, and coalitions form because they are mutually beneficial. People are stronger when they are part of a group. They are less likely to be picked on, and they are more likely to find support and help in times of need.

Game theory provides a clear framework to understand why sustained cooperation naturally emerges in groups of individuals: there are plenty of gains from cooperation. From this, rules of cooperation can emerge. We follow these rules every day when we respect the traffic signs, when we stop at the supermarket checkout to pay, and when we remain polite with people we disagree with.

Evolutionary psychologists John Tooby and Leda Cosmides stressed that the highest downside risks we face in our lives might require specific groups whose support in these times of need can serve as insurance.

For hunter-gatherers, illness, injury, bad luck in foraging, or the inability to resist an attack by social antagonists would all have been frequent reversals of fortune with a major selective impact. The ability to attract assistance during such threatening reversals in welfare, where the absence of help might be deadly, may well have had far more significant selective consequences than the ability to cultivate social exchange relationships that promote marginal increases in returns during times when one is healthy, safe, and well-fed. — Tooby and Cosmides (1996)

One challenge is that reciprocating with other people is only mutually beneficial if both can participate. People in dire need of help are often in situations where they cannot reciprocate for a long time. Hence, our ancestors faced what Tooby and Cosmides call the banker’s paradox. Just as people find it hardest to borrow money from bankers when they need it most, they may also find it hardest to get support from others when they are in their most desperate situations.

Our psychological predispositions when choosing friends likely reflect this need to find people we can trust to turn up in our direst times of need.

The principles of friendship choice

Tooby and Cosmides criticised the simple explanation of reciprocity as an “I scratch your back, you scratch mine” type of deal that one might infer from a superficial reading of game theory, such as the tit-for-tat model of the emergence of altruism.2 They argue instead that reciprocity takes place in long-term partnerships that require careful initial choice and ongoing maintenance. They propose several principles likely at play.

1 - How many friends you already have. Any friendship takes time, so we are less likely to add new friends when we already have many.

prisoners of space and time, have finite time and energy budgets, and cannot be in more than one place at a time. The decision to spend time with some individuals is, therefore, the decision not to spend time with others. — Tooby and Cosmides

2 - The benefits (broadly defined) from having this person as a friend. Benefits can take many forms. Is this person handy and helpful? Are they likely to be available when we need help? Are they knowledgeable and able to provide useful advice? Are they well connected and able to open social doors for us?

3 - Ease of understanding each other. Are you good at grasping what the other wants and thinks? Mutual mind-reading is often key to coordinating effectively and solving problems together.

4 - Whether you are valuable to them. A person is more likely to stay by our side if we are valuable to them. Hence, being valuable to someone makes that person valuable to us.3

5 - Shared preferences and goals. People with aligned interests will find it easier to cooperate to achieve their joint aims.

Loyalty bonds and commitments

Choosing friends is the first step. Making that group work effectively as a friendship group is another challenge.

A key requirement for groups to work together is cohesion. What is cohesion? It is the ability to act together as a group, with people putting the group’s goals above their own. In a group of students working on an assignment, or in a team of office colleagues on a project, it means that people pull their weight instead of shirking. In a sporting team, it means everybody putting in their best effort. In a military platoon, it means each member being willing to take the right amount of risk (not too little, not too much) for the group to have the best chance to succeed.4

The difficulty is that people are typically willing to be team players only if they are confident others will be too. Nobody wants to be the quarterback holding on to the ball a few extra seconds to make the best pass when the blockers are not doing their job to protect him. There is, therefore, a key challenge of trust in groups: whether members can rely on one another to act collectively when needed. In our ancestral past, groups that were cohesive were more likely to succeed in collective actions such as hunting big game, winning wars, or building large projects. Hence, evolution has favoured the emergence of cognitive tools that help us build trust within groups: social bonds.5

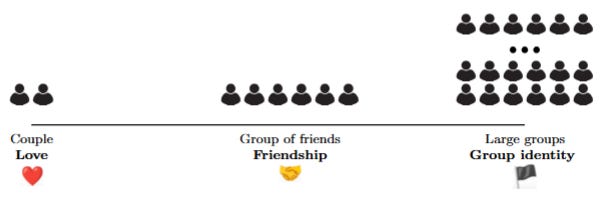

Social bonds are the emotions and feelings that tie us to others: love in a partnership, friendship within a group of friends, or social identity in larger groups such as nations and religions.

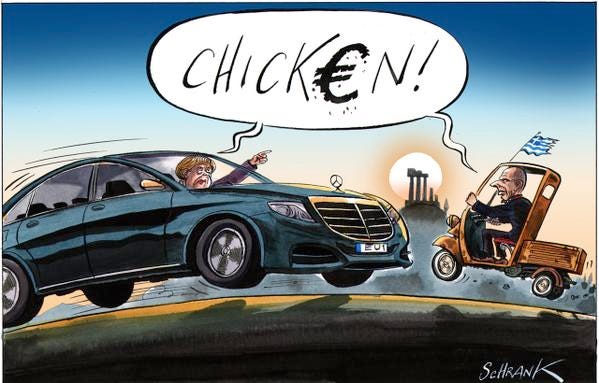

Game theorist Thomas Schelling (1960) pointed out that one is often better off in strategic interactions by committing oneself to a course of action.6 In his famous book Passions within Reason (1988), economist Robert Frank developed the idea that emotions can play a key role in social interactions by acting as commitment devices.

Two people who are considering cooperation might be concerned about each other’s intentions to invest properly in the partnership. If both experience and display genuine emotional bonds, this can serve as a signal of commitment and reassure the other that they can be trusted. As a consequence, both partners may feel confident enough to engage and invest fully in the relationship. 7

Signals of friendship

Signals of commitment

For these emotions to work and generate trust, two things are required. First, the emotions need to be real. If friendship feelings were always a pretence, there would be no reason to believe in them.8 Second, they need to be visible to others. As ironically put in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove, a commitment device is only useful if others know about it.9

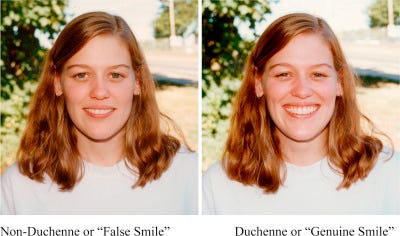

Hence, the signalling of friendship bonds is pervasive in friendship interactions. People sacrifice their narrow self-interest and expend time and resources on their friends.10 The signals of friendship are present even in our body language, which leaks cues of our social emotions. As pointed out by Ben Ho in his book Why Trust Matters (2021), genuine smiles—Duchenne smiles—are hard to reproduce if one is not truly happy. They therefore provide credible signals in friendship interactions of the positive feelings one experiences with another.

The cognitive vigilance in friendship interactions

While there is a lot of goodwill extended (because friendship feelings are real), pure, unconditional kindness would leave people vulnerable to guileful individuals who pretend to be friends while pursuing their own interests.

Friendship, therefore, requires trust to be built and then maintained. This calls for cognitive vigilance in monitoring signs of friendship, and for noticing when such signs fail to appear.

Once a friendship is well established, the main risk may not be outright betrayal, but rather that a friend’s investment in the relationship fades (for example, because they shift their attention to other friendship circles). This again calls for monitoring: signs of possible defection include reduced enthusiasm, less willingness to help, or diminished presence.

The gift economy of friendship

I explained in Optimally Irrational (2022) how the need to build and maintain trust in friendship partnerships helps explain the gift economy that takes place between friends. From formal gifts on notable occasions (e.g. birthdays) to informal gifts in everyday interactions (e.g. paying for drinks), gift exchanges are pervasive in groups of friends.

A gift is costly, and people who genuinely feel good about making their friends happy are more willing to give than those who are faking it. Gifts are therefore a credible signal of the giver’s friendly feelings. The practice of gift exchange can work as a screening device, since the willingness to participate in it reveals who is genuinely interested in a long-term relationship and who is not.11

The signalling role of gift exchanges explains their distinctive features: some delay is required between gifts, and obvious calculations about the relative value of gifts given and received should be absent. Gift exchanges are not commercial transactions where the aim is to “settle accounts.” As Tooby and Cosmides put it:

Explicit contingent exchange and turn-taking reciprocation are the forms of altruism that exist when trust is low and friendship is weak or absent, and treating others in such a fashion is commonly interpreted as a communication to that effect. — Tooby and Cosmides

This logic explains the awkwardness of commercial transactions in friendship relations. Offering to pay for dinner when you are invited to someone’s house would be interpreted as rude. It would, in effect, reject the friendship-building gift exchange by attempting to replace it with a low-commitment transaction.

Another key feature of gift exchange between friends is that, while people do not count their pennies as in a market exchange, there must be some symmetry. If there is a systematic asymmetry in the value of gifts, one recipient has a material interest in the exchange. Participating therefore does not signal that person’s genuine friendship. Hence, the seemingly paradoxical aspect of friendly gift exchange: nobody keeps precise count, but everybody is attentive to the possibility of systematic imbalance.

These logics of gift-giving were classically demonstrated by sociologist Marcel Mauss in his essay The Gift (1990), which studied gift exchanges among Native American populations on the Northwest Coast of North America and in the Trobriand Islands of New Guinea.

Mauss argued that behind the apparent generosity of the gift-giving practices, there were strict rules of obligations: the timing and the level of the reciprocation mattered greatly, and refusing to reciprocate was akin to declaring war. — Page (2022)

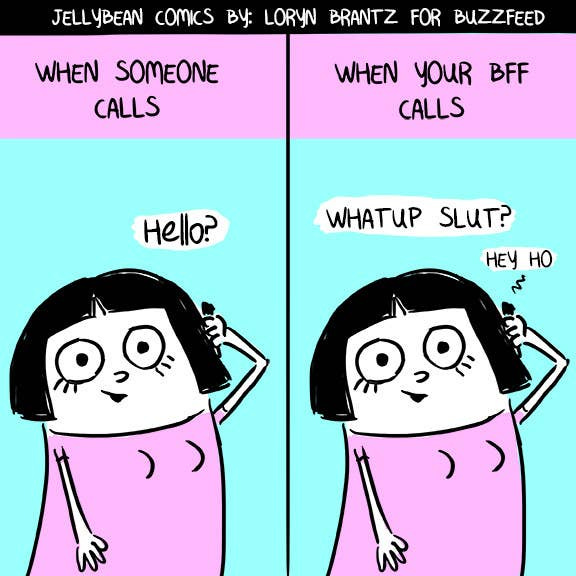

The signalling value of bantering

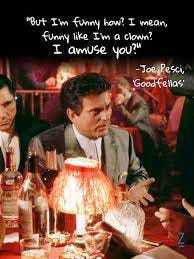

A seemingly surprising aspect of friendship interactions is bantering, which often looks like people treating their friends worse than their non-friends. As I argued in Optimally Irrational (2022), bantering can act as a signal of closeness, since only those who are genuinely close can afford to make potentially offensive digs at each other.

Bantering and mocking each other is common in groups of friends where such behaviour can be safely interpreted as not signalling a negative intent. If anything, the ability to banter and mock each other can then become a signal of real closeness in friendship, and somebody who stays too polite may signal a lack of confidence in the closeness of the relationship. — Page (2022)

A popular trope in comedy is when someone who is not close claims closeness by bantering or mocking in ways that only a real friend could. The result is usually awkward disapproval, revealing that the person has misjudged the strength of the relationship. An excellent illustration is Joe Pesci’s ominous comeback line, “I amuse you?” to somebody who said he was “a funny guy”. Saying that someone is “funny” could be a friendly compliment or a condescending jab. How it is interpreted depends on the closeness of the relationship.

The exchange of secrets

A feature of friendship groups is the intensity of private information and secrets shared both about oneself and about others. Both types of information are highly useful for people to learn about others and form a reputation.

Gossip, the exchange of non-public information about others, is pervasive in social interactions. It is valuable because it provides insights that help people navigate social life. But talking behind someone’s back carries costs. There is the potential cost that the target of the gossip may find out, which can damage one’s reputation. And there is the direct cost that simply engaging in gossip may signal to those we are speaking with that secrets are not safe with us, which can undermine their trust. Gossip is therefore a double-edged sword. You gain and provide useful information, yet you also risk reputational damage. For this reason, there is an optimal level of gossip one can safely engage in.

Beyond gossip about others, friends also exchange secrets about themselves—information they would not want revealed publicly. At first glance, this seems puzzling: why share potentially damaging information? The answer, again, lies in Schelling’s insight about commitment. By disclosing a personal secret, we make ourselves vulnerable and thereby commit to maintaining the friendship. To betray the relationship would risk having the secret exposed.

Sharing secrets is therefore a credible signal of commitment to friendship. Those who disclose little are often described as “guarded,” a term tinged with suspicion about whether the strength of their friendship can be fully trusted.

The willingness to exchange secrets also helps explain the practice, common in friendship groups, of sharing mind-altering substances—alcohol in particular—that lower inhibitions and make people more likely to talk openly. The link between drinking and trust is captured in the quip attributed to American comedian W. C. Fields:

Never trust a man who doesn’t drink. — Fields

Friendship groups’ internal hierarchies

A group of friends is usually not entirely flat, giving everyone the same standing and respect. Instead, it often features an internal hierarchy: some people are more central to the group, while others are more peripheral and could leave, or be left out, with only a limited impact on the group’s persistence. Why does such a hierarchy exist? How does it emerge? Why isn’t everyone simply “equal” in a friendship group?

The answer is that coalitions are often like Russian dolls: within a coalition, there are sub-coalitions, and within those, smaller sub-coalitions again. In friendship groups, the central clique is a smaller group, large enough to influence decisions for the wider group, for example, deciding what activities to do together or who gets accepted into the group.

Our psychology is highly attuned to these dynamics. We care not only about being in a group but also about our place within it: whether we are close to the centre or drifting toward the periphery. We constantly monitor our standing, worrying about signals that we might be moving outward (for example, when a best friend starts spending more time with someone else) and feeling reassured or proud when we move closer to the centre (for example, when a central member of the group values our input or includes us in key decisions).

Gender differences in friendship groups

In his book The War of the Sexes (2012), economist Paul Seabright conjectured that women and men differ in the features of their social networks, with women having smaller networks with “strong ties” that require considerable investment to maintain and men having larger networks with “weak ties” that require less investment.12

The available data supports key elements of this conjecture. In regards to the nature of friendship networks, women tend to include closer people, often family members, while men include more distant contact.13 In regards to activities with friends, women spend more time just talking with friends, while men are more likely to do practical things.14 The literature on gender differences in friendship also points to the greater willingness of women to share personal stories and emotional feelings with their friends.15

female same-sex friendships tend to engage in interaction, supportiveness, and openness more than male same-sex friendships. — Oswald, Clark and Kelly (2004)

The evidence does not strongly suggest differences in the size of friendship groups or broader networks, as Seabright initially conjectured.16 But it does support his view that men’s ties tend to be weaker and require less maintenance, while women’s ties tend to be stronger and more demanding of investment.

Why?

Why do such gender differences exist? Sociologists often explain them as the result of socialisation (men and women are taught to behave differently) and of social opportunities typically advantaging men. This is the view put forward by Claude Fischer and Stacey Oliker:

We propose that the differing positions of women and men in the work force, in marital roles, and in parenthood create different sets of opportunities for and constraints on friendship building — Fischer and Oliker (1983)

Similarly, Gwen Moore suggested that these differences reflect women’s traditional gender role as “kinkeepers”:

This result is consistent with women's roles as “kinkeepers,” persons who keep members of the extended family in touch with one another. — Moore (1990)

There is, however, a more fundamental explanation. As ecologist Bobbi Low put it in Why Sex Matters (2015):

Coalitions, like so many other phenomena, can be a reproductive strategy; and if this is true, male and female coalitions will tend to be different.

The anthropologist and evolutionary psychologist Sarah Hrdy emphasises the critical role of support groups for women in her book Mother Nature (1999). Raising children in our ancestral past was especially challenging. Human children are unusually immature at birth and dependent for many years, requiring constant care. Mothers were more likely to succeed in raising children if they were embedded in tight networks of supportive allomothers (“all the caretakers other than the mother who help care for or provision young”).

The real constraint on working mothers has little to do with imagined ideals of Pleistocene motherhood, far more to do with locating and enlisting reliable, motivated, long-term allomothers. Human infants need mothers and allomothers to keep them warm, safe, mobile, stimulated, clean, fed, hygienically hydrated, and, most important, to communicate tenderly and responsively their commitment to go on caring. Hour by hour, supplying this kind of care is tedious. — Hrdy (1999)

Supportive allomothers likely engaged in reciprocal arrangements: you help me with my child, and I’ll help you with yours. Because childcare is so costly in time and resources, the number of such reciprocal relationships was necessarily limited. Moreover, entrusting children to others required very high levels of trust. As Hrdy observes:

Like a modern working mother agonizing over when to go back to work, or whether or not to leave her baby at the nearby daycare center, whose staff she does not quite trust, mothers have always found themselves calculating whether it's safe to leave baby with an allomother. — Hrdy (1999)

Since childcare is difficult to monitor (one may not know how a babysitter treats a child when unsupervised) tight, high-trust coalitions among women would have been favoured.

This, I conjecture, helps explain the gender differences in friendship groups. Women set a higher bar in what evolutionary psychologists call “partner choice” (Barclay 2016). Female friendships are often closer and more frequently involve family members. Kin are a safer source of support in childcare, while close friends can be chosen and monitored in ways that build trust and safeguard reputation. Close friendship ties, however, require continual investment. High trust is not automatic; it must be reinforced through regular interaction and mutual care.

On the other hand, men’s coalitions in ancestral times were likely less centred on a specific task. They may have involved larger groups of people, where the defection of any individual was less costly and more publicly observable. Male groups appear to have cared about loyalty and to have monitored signs of defection, but defection in collective actions might have been easier to detect than defection in more private settings. If so, this would have placed a lower bar on the level of trust that needed to be built into each partnership within a male coalition.

Perpetual calculation coalitions of males are both unstable and flexible: they form and dissolve according to the needs of the moment, and breakdown of cooperation at one moment is rarely inimical to its reestablishment a short while later. Female coalitions are more stable and loyal, but although female friends rarely turn on one another, grudges are equally rarely settled, and never just in order to take advantage of some passing foraging opportunity. — Seabright (2012)17

The gender differences in friendship networks are not the result of “defects”—with men being socially impaired or women overly emotional. Nor are they merely the product of cultural “brainwashing.” They are more likely the reflection of deep evolutionary differences in the challenges faced by men and women, and of the best coalitional strategies to solve them.18

How this explains the deep features of friendship interactions

Back to Riley

We can now return to the case of Riley and her friendship dilemmas. Her choice is between her old group of friends, with whom she has an existing commitment and real friendship feelings, and the option of joining the group of top hockey players. The new group Riley wants to join revolves around the team captain, who is popular and charismatic. Being part of that group is bound to elevate Riley’s standing in the hockey team and, likely, in her broader school social circles.

Her old friends feel betrayed because she is breaking the friendship partnership they had built together. By forming and nurturing their relationship, Riley had de facto committed to them. They had invested in her as a partner, and now they have lost her. Riley, in turn, feels both the guilt of breaching trust and the sadness of abandoning her old friends, while also experiencing the pull of joining a high-status group.

This mix of warm feelings and strategic motives makes sense once we understand the deeper strategic layers at play in friendship groups and the strategies we use, consciously and unconsciously, to navigate them.

Is it all fake?

Talking about strategies and calculations often makes us uncomfortable when it comes to friendship. Does this mean it is all fake?

The picture I have presented here suggests something very different. Friendship feelings are real, and they are central to how we interact with friends.

the phenomenology of friendship unsurprisingly reflects the pleasure you experience in someone’s company, the pleasure you feel knowing they enjoy your company, the affection generated by an ease of mutual understanding, the desire to be thoughtful and considerate, the satisfaction in shared interests and tastes, how deeply you were moved by those who helped you when you were in deep trouble, how much pleasure it gave you to be able to help friends when they were in trouble, the trust you have in your friends, and so on. — Tooby and Cosmides

Feelings of friendship are real because their existence is part of the solution to the problem of making groups of people coordinate around high cooperation. But unconditional kindness on its own is not a viable solution. The underlying strategic nature of friendship interactions explains the whole choreography of friendship: smiles and laughter, the giving of gifts and the ostentatious absence of narrow calculation, the exchange of gossip and secrets. All of these practices make sense as ways of building trust and strengthening mutual bonds.

Friendship is thus characterised both by genuine positive feelings and by genuinely kind actions, and by a constant layer of vigilance: the anxiety that our feelings may not be fully reciprocated, and the monitoring of others’ friendship signals to detect any sign that they might be lacking.

References

Barclay, P. 2016. ‘Biological markets and the evolution of cooperation’, Current Opinion in Psychology, 7, pp. 33–38.

Benenson, J.F. and Christakos, A., 2003. The greater fragility of females' versus males' closest same‐sex friendships. Child development, 74(4), pp.1123-1129.

Benenson, J.F. and Wrangham, R.W., 2016. Cross-cultural sex differences in post-conflict affiliation following sports matches. Current biology, 26(16), pp.2208-2212.

Caldwell, M.A. and Peplau, L.A. 1982. ‘Sex differences in same‐sex friendship’, Sex Roles, 8(7), pp. 721–732.

Carmichael, H.L. and MacLeod, W.B. 1997. ‘Gift giving and the evolution of cooperation’, International Economic Review, 38(3), pp. 485–509.

Fischer, C.S. and Oliker, S.J. 1983. ‘A research note on friendship, gender, and the life cycle’, Social Forces, 62(1), pp. 124–133.

Frank, R.H. 1988. Passions within reason: The strategic role of the emotions. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Gillespie, B.J., Lever, J., Frederick, D. and Royce, T. 2015. ‘Close adult friendships, gender, and the life cycle’, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 32(6), pp. 709–736.

Granovetter, M. 1973. ‘The strength of weak ties’, American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), pp. 1360–1380.

Green, E. and Singleton, C. 2009. ‘Mobile connections: An exploration of the place of mobile phones in friendship relations’, The Sociological Review, 57(1), pp. 125–144.

Henderson, R.K. 2024. Troubled: A memoir of foster care, family, and social class. New York: Gallery Books.

Hirshleifer, J. 1987. ‘On emotions as guarantors of threats and promises’, in J. Dupre (ed.) The latest on the best: Essays on evolution and optimality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 307–326.

Ho, B. 2021. Why trust matters: An economist’s guide to the ties that bind us. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hrdy, S.B. 1999. Mother nature: A history of mothers, infants, and natural selection. New York: Pantheon Books.

Low, B.S. 2015. Why sex matters: A Darwinian look at human behavior. Revised edition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Moore, G. 1990. ‘Structural determinants of men's and women's personal networks’, American Sociological Review, 55(5), pp. 726–735.

Oswald, D.L., Clark, E.M. and Kelly, C.M. 2004. ‘Friendship maintenance: An analysis of individual and dyad behaviors’, Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(3), pp. 413–441.

Page, L. 2022. Optimally irrational: The good reasons we behave the way we do. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reis, H.T. 1998. ‘Gender differences in intimacy and related behaviors: Context and processes’, in Canary, D.J. and Dindia, K. (eds.) Sex differences and similarities in communication. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 203–231.

Seabright, P. 2012. The war of the sexes: How conflict and cooperation have shaped men and women from prehistory to the present. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schelling, T.C. 1960. The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schelling, T.C. 1978. ‘Altruism, meanness, and other potentially strategic behaviors’, American Economic Review, 68(2), pp. 229–230.

The book of Sirach is part of the Catholic Bible, but not of the Protestant one.

The vision they criticise is only a narrow interpretation of the game theoretic results as the richer patterns of friendship formation they suggest is compatible with the formal models about cooperation in groups. See my post on reputation.

Tooby and Cosmides call this a “mirroring effect.”

As you unpack coalitions within coalitions, the final outcome may be the discovery of small groups without a clear hierarchy. These can function as “grand coalitions,” giving all members an equal standing.

For the game theory–interested reader: in Optimally Irrational I explain how these problems often boil down to a collective Stag Hunt game.

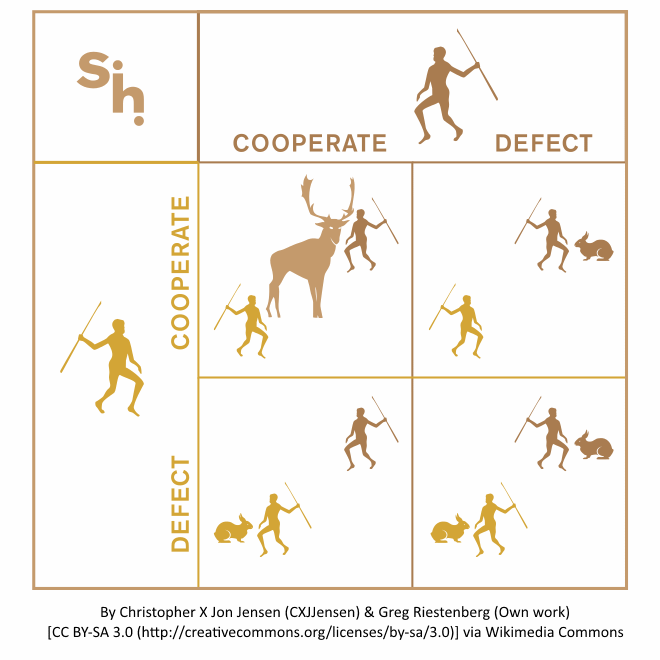

First described by Rousseau, the Stag Hunt involves two hunters who can either wait together for a stag or each choose to hunt a hare alone. Hunting the hare provides a guaranteed but smaller payoff. The stag provides a higher payoff, but only if both cooperate. If one defects and goes after a hare, the other—left waiting—gets nothing.

At first sight, the choice seems obvious: sharing the stag provides the highest payoff. But the risk is that cooperation requires mutual trust. Waiting for the stag is risky because it depends on the other also waiting, while going for the hare always pays off. Players must choose between the risky, high-payoff strategy (stag) and the safe, low-payoff strategy (hare).

Whenever players trust each other to “do the right thing” for the group, they cooperate and get the stag. Without trust, they defect and settle for hares.

A slightly more technical point: the Stag Hunt has two equilibria: cooperate/cooperate and defect/defect. Hence both cooperation and non cooperation can be stable situations in groups. Note that in games that seem to have only one equilibrium, like the one-shot Prisoner’s Dilemma, when the game is repeated indefinitely the Folk Theorem applies: there are multiple equilibria. The repeated game thus resembles a Stag Hunt, with the challenge being how to coordinate on a good equilibrium with high payoffs from cooperation over time.

In plain English: equilibria of repeated games take the form of conventions or rules about how to cooperate and how to divide the gains. A key challenge in repeated interactions is coordinating on the right conventions so cooperation can emerge and generate higher payoffs. But people will only follow rules if they believe others will too. You are likely to follow traffic laws carefully in Singapore, but you may feel silly doing so if you are the only one following them in Cairo. Shared trust that others will act in the group’s interest is therefore critical for cooperation.

For evolutionary biologists: this is not a naïve group selection argument. The gains from cooperation arise at equilibrium, where it is individually rational to act collectively. What is selected are psychological traits that help us coordinate on better equilibria.

Consider a drive hunt where beaters flush animals toward waiting hunters. If even one beater is careless and leaves a gap, the prey may escape. But if every beater knows that all the others are doing their best, each one has reason to do the same—this is the cooperate/cooperate equilibrium of the Stag Hunt.

Psychological features that generate collective trust, enabling coordination on the cooperative equilibrium, would be selected for, because they are individually beneficial. The mechanism can proceed through culture–gene coevolution: cooperative conventions emerge culturally, and then individuals better tuned to use and navigate these conventions are favoured by selection (e.g. conditional cooperators).

Committing is abandoning some course of action one might have found appealing in the future. A priori, more choices seem better, but Schelling showed that in some contexts restricting one’s options can be strategically advantageous.

For example, in bargaining situations resembling a game of chicken—where both sides push until one backs down—each may want to reduce its option to retreat. A good illustration is the 2015 Greek referendum on the bailout plan proposed by European creditors. The referendum seemed to tie the government’s hands. [Yet the creditors did not budge, and the Greek government ultimately backed down when faced with the risk of being expelled from the Eurozone.]

The insight that commitment can be strategically advantageous was one of Thomas Schelling’s most important contributions. Later, Jack Hirshleifer (1987) and Robert Frank (1988). Note that without presenting this idea as such, Thomas Schelling (1978) had suggested in a one-page article that altruism could be strategic in itself.

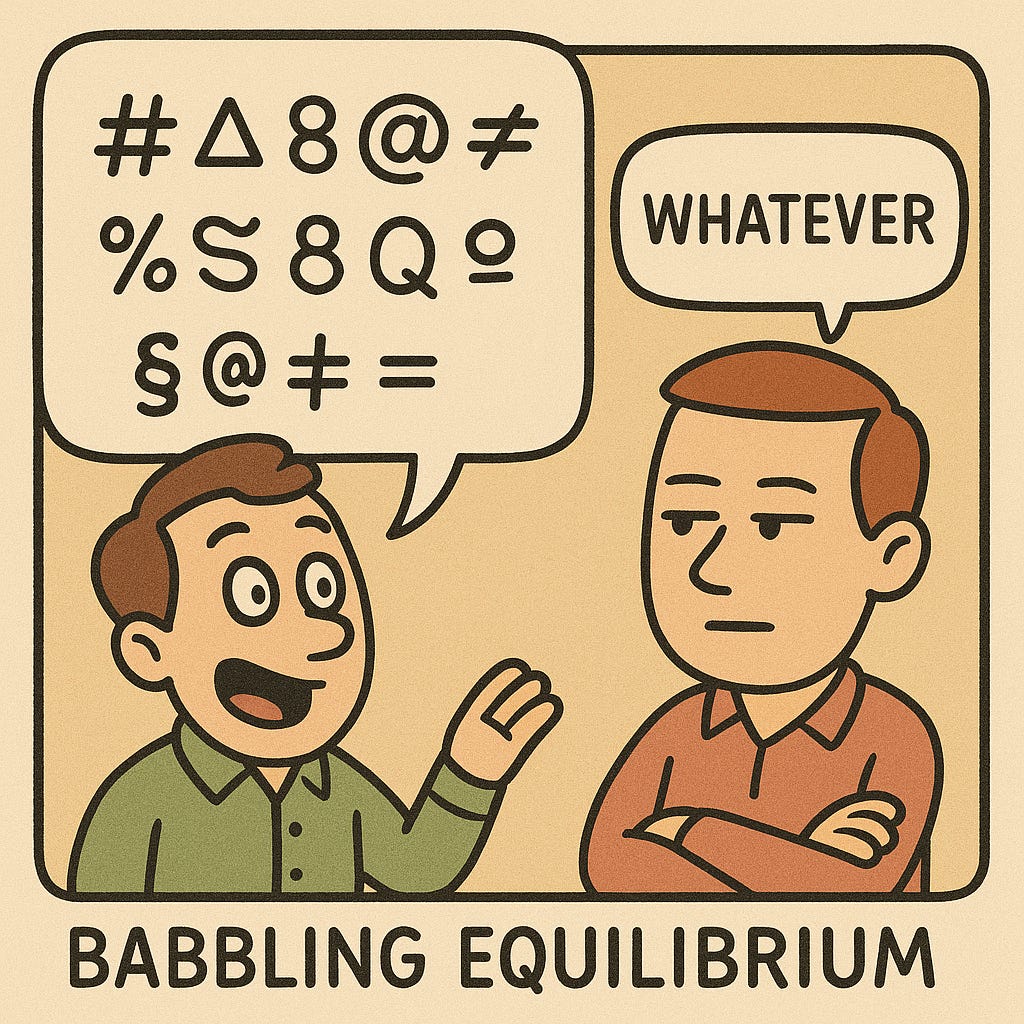

Why do people, generation after generation, continue to believe others when they signal friendship? Why not assume that all such claims are lies? A key game-theoretic insight is that “universal lying” is not a stable outcome. If everyone lied about friendship, no one would believe such signals. Game theorists call this outcome a babbling equilibrium.

This film features a ‘Doomsday machine’ that automatically reciprocates to a nuclear attack with a mass counter-attack. The purpose of the machine is to commit to retaliation and leave no doubt in the enemy’s mind, removing the possibility that humans might hesitate before engaging in mass nuclear warfare. The screenplay was directly inspired by Thomas Schelling’s work on game theory in the Cold War context.

In large groups, this logic explains many seemingly puzzling customs: dress codes, body modifications, culinary practices, dances, or collective singing. These practices allow individuals to publicly signal their group loyalty, and for others to monitor those signals.

Violating such customs can incur strong sanctions. If you refuse to eat, dress, or sing like the group, you signal that personal preference outweighs group loyalty. If you cannot signal allegiance in these small ways, how can the group trust you in larger, riskier endeavours?

This idea was formalised by Carmichael and MacLeod (1997).

The notions of strong and weak ties come from the sociologist Mark Granovetter (1973).

See the highly influential study by Caldwell & Peplau (1982).

In a study of Pakistani-British men’s and women’s use of mobile phone, sociologists Green and Singleton found that

Whilst men used mobiles primarily to arrange activities with friends, women’s use of mobiles demonstrated the creation and maintenance of a space devoted to ‘doing friendship’ — Green and Singleton (2009)

In a study on same-sex friendship using participants in California, sociologists Caldwell and Peplau found that men gather in larger groups of friends while women tend to have more intimate gatherings.

Men typically get together with more friends than women, while women more often meet their best friend just to talk — Caldwell and Peplau (1982)

See Caldwell and Peplau (1982) and Reis (1998).

See Caldwell & Peplau (1982) and Gillespie, Lever, Frederick & Royce (2015).

This difference pointed by Seabright is backed by empirical evidence, with female friendship being less likely be repaired after conflict, while males are more willing to re-establish interactions (see Benenson and Christakos 2003; Benenson and Wrangham, 2016).

Illustrating this fact, classical literature depicts idealised cases of male friendship emerging after a physical fight. In Homer’s Iliad, Diomedes and Glaucus meet as enemies on the battlefield but, upon discovering a bond of ancestral guest-friendship, lay down their arms and exchange armour. In Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West, Sun Wukong and the pig-demon Zhu Bajie first clash violently, but Pigsy eventually joins the pilgrimage, and their rivalry turns into camaraderie.

In his autobiographical Troubled (2024), Rob Henderson describes this move from violent conflict to friendship in his neighbourhood: “fights here were more frequent, but it was also more likely that friendships formed and endured after fighting.”

These differences arise from the different strategic challenges faced by women and men in their friendship networks. Female friendships tend to be strong ties: they involve closer relationships and forms of allomothering support that take place in private, less observable settings. Because what happens in such contexts cannot easily be monitored, only highly trusted partners are admitted. Breaches of trust, whether through conflictual behaviour or a lack of friendliness, send strong signals of unsuitability and can be hard to repair. Male friendships, by contrast, often take the form of weaker ties, built around collective activities where actions are public and easier to observe. In such contexts, the threshold of trust required for inclusion is lower, because the strategic challenge is different: the key problem is coordinating to reap the benefits of collective work. Conflicts can therefore more readily be put aside so that mutually beneficial cooperation can resume.

Because these strategies were shaped to solve ancestral problems, they sometimes misfire in modern contexts. For example, Seabright suggests that women’s tighter, trust-based networks may disadvantage them in modern careers, where weak ties to distant acquaintances often provide access to more diverse opportunities.

You may want to change the part about the quarterback away from referencing the defense to instead reference the blockers failing to protect the quarterback.