The importance of a good reputation

What reputation is and how it works

In a famous commencement speech at Kenyon College in 2005, David Foster Wallace told the following story:

There are these two young fish swimming along when they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way. The older fish nods at them and says, ‘Morning, boys. How's the water?’ The two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, ‘What the hell is water?’”

The point of the story, Wallace continued “is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about” Like in this story, it can be surprisingly hard for us to understand some of the features of the social world we live in. In this post, I discuss one of these features: reputation. People clearly seem to care about it, but what is it and how does it work?

In her book Reputation (2018), the philosopher Gloria Origgi describes reputation as a “second self that guides our actions sometimes even our interests.” She refers to the fact that people are sometimes willing to incur substantial material costs to protect or enhance their reputation. In a recent tweet, Rob Henderson presented such an example from a story in Ancient China.

Origgi points out that, paradoxically, it is not straightforward to understand how reputation works:

Reputation is shrouded in mystery. The reasons it waxes or wanes and the criteria that define it as good or bad often appear fortuitous and arbitrary. Yet reputation is also ubiquitous. […] It seems to insinuate itself into the most intimate recesses of our existence. - Origgi (2017)

In a recent review of the literature on reputation, psychologist Jilian Jordan (2023) remarked that “our understanding of reputational phenomena has been limited by a disconnect between the game-theoretic and empirical reputation literatures.” It is certainly true that while we observe reputation’s importance in social interactions, game theorists have found it difficult to delineate its nature and mechanisms.1 Nonetheless, advances in game theory—including some developments that are not widely known—can help us understand it. I present here, in simple terms, some of the insights from that literature on what reputation is and how it works.

What is reputation?

The notion of reputation comes in when considering social interactions taking place over time. A business’ reputation for providing quality goods comes from its past interactions with customers, a newspaper's reputation for being unbiased comes from its past articles, and a person’s reputation for being honest comes from their past record. A feature of these examples is that reputation is relevant when you consider whether someone or a company is worthy of your trust when you interact with them. A good reputation in these examples comes with a record of having acted “well” in social interactions and being trustworthy.2

Reputation with mindless agents

It is often suggested that economics and game theory predict that people should behave selfishly in every interaction. In that perspective, there is no point in trusting other people to do the right thing towards you. However, this view is not accurate. One of the key contributions of game theory is to show that cooperative behaviour can perfectly emerge in social settings where people interact repeatedly. I explained in a previous post how this idea stems from the Folk Theorem:

The Folk Theorem, a cornerstone of game theory shows how cooperation can be rationally sustained in repeated interactions. The key idea from the Folk Theorem is simple: if individuals value the potential future benefits of sustained cooperation, it can be rational for them to resist the temptation to defect in the present. Trying to take advantage of others now can bring benefits in the short term, but it may also mean losing their trust, their willingness to cooperate in the future, and therefore the stream of future rewards from cooperation. The risk of losing future opportunities to cooperate can therefore act as a deterrent, enforcing cooperative behaviour in the present.

To give an example let’s consider John who regularly buys bread at Jane’s boulangerie. This regular exchange is mutually beneficial: Jane receives an income from selling bread and John gets bread he would not be able to cook himself. On a given day Jane could decide to sell yesterday’s (somewhat stale) loaves of bread to save on costs, rather than baking new ones. This would not be very kind to John who would pay full price for bread of lesser quality. However, if Jane were to do so, she would risk disappointing John and potentially losing him as a customer. Thus, the anticipation of future exchanges with John incentivises Jane to sell fresh loaves every day. This intuition extends Adam Smith’s famous quote from the Wealth of Nations.3

In their authoritative book on game theory about the subject, Repeated Games and Reputations (2006), George Mailath and Larry Samuelson point out that the notion of reputation can be used to describe this result. “In this approach, the link between past behavior and expectations of future behavior is an equilibrium phenomenon.” In other words, cooperation is sustainable in the long run because people only cooperate with people who have been cooperative in the past.

The notion of direct reciprocity describes such reciprocal behaviour between two individuals. An illustrative example of this concept is the scenario where John continues to patronise Jane’s bakery as long as she provides him with fresh loaves of bread. In this context, Jane’s consistent history of fulfilling her part of the mutual exchange effectively constitutes her “reputation”.

This explanation for cooperation between two people can be extended to a population of people interacting regularly with different people. The biologist Alexander (1987) proposed the notion of indirect reciprocity to describe a situation where people cooperate with each other, even when they only meet other people once. Such behaviour can be sustainable if people’s history of cooperation gives them a public record.4 People can adopt as a rule to only cooperate with people who have a good public record.5 When everybody follows this rule, everybody has an interest in cooperating with others so as not to get a bad public record. These public records can also be thought of as people’s reputations.6

These approaches are very influential in game theory, but they seem to miss a key aspect from our intuition of how reputation works. When we think that somebody has a good or a bad reputation, it seems to tell us something more than just about their past record; it seems to also tell us something about their likely behaviour in the future. But “nothing in the repeated game captures this intuition” (Mailath and Samuelson, 2006).

To caricature, these explanations of reputation could describe mindless robots simply following the rule to cooperate with robots that have a good record of cooperation.7 They would not need to have any thoughts about whether other robots are nice or trustworthy. In his highly influential book The Biology of Moral Systems, Alexander stressed that, on the contrary, the assessment of potential partners is a key part of our social interactions.

Humans tend to decide that a person is either moral or not, as opposed to being moral in one time or context and immoral in another […] We use motivation and honesty in one circumstance to predict actions in others.” - Alexander (1987)

Reputation tells us something about people

Somebody’s reputation seems to tell us something about that person and, for that reason, about their future behaviour. To explain this, one needs to consider reputation as emerging from a situation where people differ in their traits.8 People may be more or less inclined to be cooperative. In that case, observations of past behaviour provide an informative signal about these unobserved traits.

In that perspective, people’s traits can vary in many ways and past cooperation informs us about their unobserved psychological traits. People are more likely to cooperate in the future if they are kind, empathetic, or even patient (and therefore value the long-term benefits of a partnership).9 When we choose people to interact with, we want to be confident that they have such traits so that we do not wrongly give them our trust. In a restaurant, we hope that the food has been made according to the required level of hygiene. When buying something on eBay, we hope that the goods will arrive in the condition described in the advert. When telling a personal story to a friend, we hope it won’t be widely shared.

A person’s reputation can then be defined as other people’s beliefs about that person’s propensity to behave well in social interactions (given that person’s past record). Reputation plays an important role in partner choice, how we choose people we want to interact with (Baumard et al., 2013).10 As a consequence, people need a good reputation to be successful socially, and everybody has some interest in behaving well to build a good reputation.

The best way to send the signal that cooperating with oneself pays is to actually behave as such, which is the very idea of having a good reputation - André et al. (2024)

Why reputation is valuable and can be lost in an instant

Reputation is valuable

Once understood like this, it becomes clear why reputation matters. A good reputation carries the prospect of future benefits from social interactions. It positions us favourably to be selected as partners, entrusted as colleagues, and backed as leaders. In that sense, it is “a universal currency that can be used in any other social interaction.” (Milinski, 2015)

Reputation is earned slowly and lost fast

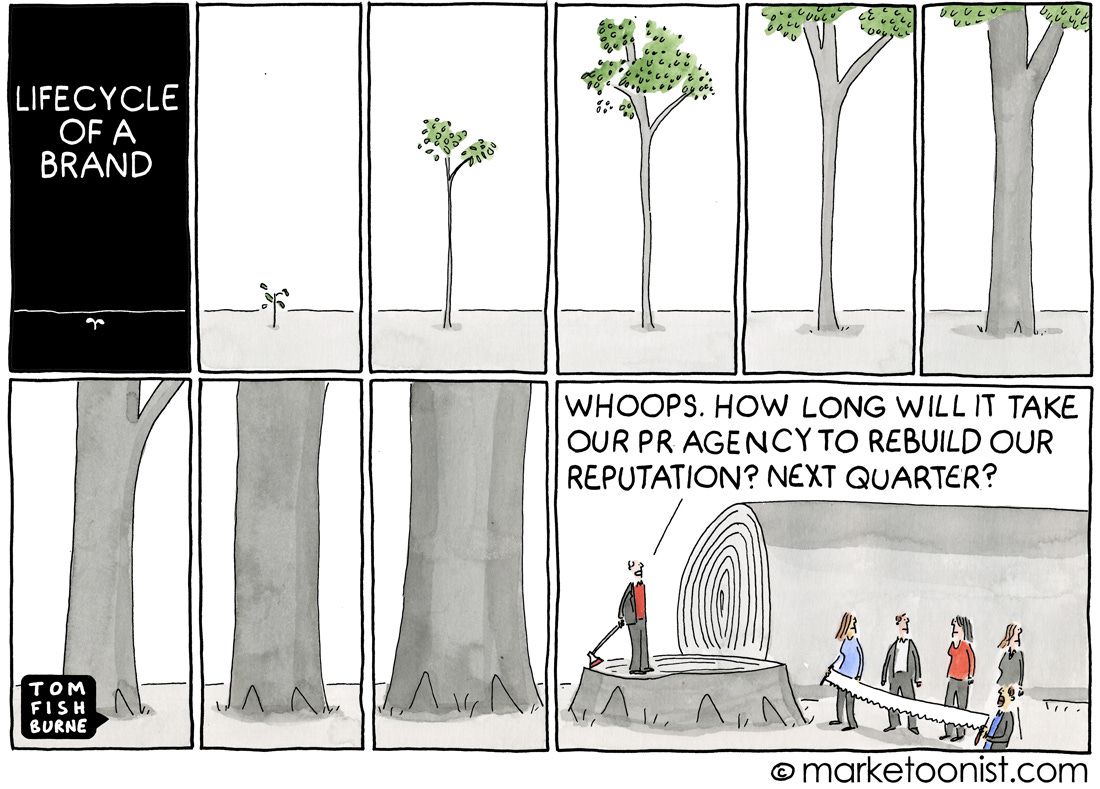

An important feature of reputation is that it takes time to build up but can be lost very fast. This asymmetry makes sense when we appreciate that reputation is the result of a signalling game where our record of good deeds is used as evidence that we are cooperative/trustworthy.

A good reputation comes with benefits and these benefits may attract some people who are not inherently motivated to be cooperative. Thus, individuals trying to build a good reputation can fall into two categories. First, there are those with genuinely good intentions who will always cooperate because it aligns with their internal preferences. Second, there are individuals who merely play along, and could very well adopt uncooperative behaviour if they believed they could escape detection.

Any misstep is therefore a strong signal that behind seemingly good behaviour, a person might be feigning their internal quality. Building a reputation requires time because the absence of missteps over a period is the most reliable indicator that a person is truly inherently cooperative. This reputation can collapse instantly if a clear misstep is observed—one that a genuinely cooperative person could not have made in good conscience.

Caring about one’s reputation is not irrational

Our success is deeply dependent on our ability to cooperate successfully with others. It is, therefore, understandable to place significant value on our reputation and to be highly concerned when it is adversely affected. Reputation is a capital of social trust built from a steady record of good behaviour in past social interactions. A person’s place and prospects in society depend on this social trust. A loss of reputation comes with very practical and material costs: the friends you lose, the colleagues who shun you, the opportunities that are not offered to you, and so on. It is therefore not surprising that we can behave as if our reputation is a “second self that guides our actions” and sometimes go to great lengths to protect it.

We can unpack what reputation is and how it works: it is the perception others have about our inner traits that they cannot directly observe. Building a good reputation requires time and effort, but it offers benefits because it serves as a credible signal to others that they can trust us when we interact with them. In the next post, I will use these insights to explain a wide range of seemingly strange features of how reputation works (and sometimes does not work well) in society.

References

Alexander, R., 1987. The biology of moral systems. Transaction Publishers.

André, J.B., Fitouchi, L., Debove, S. and Baumard, N., 2022. An evolutionary contractualist theory of morality.

Baumard, N., André, J.B. and Sperber, D., 2013. A mutualistic approach to morality: The evolution of fairness by partner choice. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(1), pp.59-78.

Gintis, H., Smith, E.A. and Bowles, S., 2001. Costly signaling and cooperation. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 213(1), pp.103-119.

Jordan, J.J., 2023. A pull versus push framework for reputation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

Kandori, M., 1992. Social norms and community enforcement. The Review of Economic Studies, 59(1), pp.63-80.

Lie-Panis, J. and André, J.B., 2022. Cooperation as a signal of time preferences. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289(1973), p.20212266.

Mailath, G.J. and Samuelson, L., 2006. Repeated games and reputations: long-run relationships. Oxford University Press.

Mas-Colell, A., Whinston, M.D. and Green, J.R., 1995. Microeconomic theory (Vol. 1). New York: Oxford university press.

Nowak, M.A. and Sigmund, K., 1998. Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature, 393(6685), pp.573-577.

Origgi, G., 2017. Reputation: What it is and why it matters.

Osborne, M.J. and Rubinstein, A., 1994. A course in game theory. MIT press.

Roberts, G., 1998. Competitive altruism: from reciprocity to the handicap principle. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 265(1394), pp.427-431.

Roberts, G., Raihani, N., Bshary, R., Manrique, H.M., Farina, A., Samu, F. and Barclay, P., 2021. The benefits of being seen to help others: indirect reciprocity and reputation-based partner choice. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 376(1838), p.20200290.

Sugden, R., 2004. The economics of rights, co-operation and welfare (pp. 154-165). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Suzuki, S. and Kimura, H., 2013. Indirect reciprocity is sensitive to costs of information transfer. Scientific reports, 3(1), p.1435.

It is obvious that reputation matters greatly for economic interactions (consider the importance of reputation for a business) and for human psychology (given the effort and resources people are willing to invest to protect and enhance it). Yet, it is a concept largely absent from economic textbooks, and most students graduating in economics would not be able to define what it is and how it works within an economic model. The word “reputation” is not mentioned once in the nearly 1,000 pages of the most influential textbook in microeconomics by Mas Colell et al. (1997, 17,000 citations) and only mentioned twice in informal comments in the more than 600 pages of the classic game theory textbook by Osborne and Rubinstein (1994, 11,000 citations).

In this post, I look at the reputation for being prosocial (kind and trustworthy). Reputation can also be for other traits, for instance being tough and not being a pushover. I’ll discuss this type of reputation in the next post.

For an introduction to Adam Smith’s insights see this joint post with Koenfucius .

Such a record has been called “label”, “score” or a “standing” by different authors (Kandori, 1992; Nowak and Sigmund, 1998; Sugden, 2004).

For the readers interested in the research in that domain:

Models showing that indirect reciprocity can be an equilibrium of a game where players are regularly rematched with new players have been studied in standard game theory (Mailath and Samuelson, 2006, chap 5). They are also widely used in evolutionary game theory (Roberts et al., 2021). This approach, which tends to be more popular in biology, differs from standard game theory in that it examines decision-makers who follow fixed rules of behaviour and investigates which rule would be selected through an evolutionary process.

In the case of Jane, such a public record could be the ratings she gets on Google. To avoid getting bad ratings and losing future customers, she has an interest in selling fresh bread to all customers, even those who are unlikely to come back.

In the case of standing, only cooperation with past cooperators contributes to standing while not cooperating with players in low standing does not hurt your standing.

The previous explanation of reputation comes from assuming that repeated games are in complete information. Participants know all the characteristics of other participants. They can condition their actions on the record of past actions of other participants, but they do not learn anything from this record. When participants do not know some of the traits of other participants (e.g. preferences), the game is in incomplete information. In that case, participants form beliefs about other participants’ characteristics and these beliefs can be influenced by other participants’ past records.

For the readers interested in the research in that domain:

Models of partner choice—where people choose their social partner based on their reputation—have been developed in standard game theory (Mailath and Samuelson, chap 5) and evolutionary game theory (Roberts, 1998; Gintis et al., 2001; Lie-Panis and André, 2022).

Another argument for the partner choice explanation is the cost of maintaining a reputation system. In the label/score/standing explanation, people benefit from playing the equilibrium strategy of cooperating with past cooperators. However, maintaining a reputation system is costly (even if only in terms of cognitive ability for the participant). This reputation system is a kind of public good, therefore any cost individuals face to sustain this system of reputation may prevent it from working because everybody has an interest in free-riding by letting others do the monitoring (Suzuki and Kimura, 2013). In the signalling explanation, everybody benefits from monitoring the reputation of others because it determines whether one is going to interact with a good partner or not.

Really enjoyed this! Pre-dating some of the work you cite (though not pre-dating Adam Smith) is Robert Axelrod's work "The Evolution of Cooperation" in which he describes the 'discount parameter'--a.k.a., 'the shadow of the future'--in the context of his famous tit-for-tat strategy in a repeated interaction tournament. That seems very parallel to your example of Jane and John and their exchange of bread.

Great post! As it turns out, reputation is part of a more general process in the establishment and development of interpersonal relationships. See the work of John Thibaut and Hal Kelley on the transformation of the basic, given outcome “matrix” to a higher level “effective” matrix accumulated into attributions of dispositions (i.e., reputations), especially Kelley’s “Personal Relationships” (1979).