Happiness and the pursuit of a good and meaningful life

What is it that we pursue and why

I conclude my series on happiness with two posts addressing big questions. In this first of the final two, I examine what an adaptive understanding of happiness suggests about what we should aim for in life. This post is longer than usual due to the depth of the topic. If you’re intrigued by these questions, I encourage you to read along, as you’ll find answers rarely discussed elsewhere.

The idea that we strive for happiness in life seems almost universally accepted. Even the austere Kant asserted in Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals that happiness is a universal goal.1 But philosophical debates about what true happiness is and how it can be attained have long seemed shrouded in mystery. What defines a good life, and why? What role does happiness play, and what exactly is happiness?

Should we aim for wealth and fame? Or for family and friends? Or perhaps for a meaningful life that transcends our own perspective? It’s easy to feel lost when trying to address such questions. The literature on happiness offers little help, as it rarely converges on a single answer.

In this post, I propose that what often feels like a profound mystery of human life—with its diverse and confusing answers—becomes clear when viewed through the adaptive lens I have developed in previous posts.

Hedonism?

A natural starting point is the idea that happiness might lie in the endless pursuit of pleasures. This view—hedonism—has frequently been rejected by thinkers who argue that a happy life must involve more than pleasure alone. In Plato's Gorgias, Socrates ridicules hedonism, comparing it to living like a “leaky jar,” always seeking to be refilled with more pleasure.2

A modern portrayal of this “leaky-jar” lifestyle is found in the film Wall-E, where humans spend their days passively consuming pleasures: eating, drinking, and watching entertainment. They experience what might seem desirable sensations without effort, but the picture just seems wrong as a representation of a good life.

Our intuitive dismissal of this pleasure-filled life as a “good life” points to a critical omission in hedonism. Not long after Plato, Aristotle argued that the ultimate goal in life should not be the pursuit of pleasures—hedonia—but the contentment of living a rational, virtuous life—eudaimonia.

More than two thousand years later, the modern field of positive psychology, which investigates happiness and its mechanisms, echoes this point. In his book Authentic Happiness, Martin Seligman proposes that pleasure is only one aspect of happiness. He argues that two additional components are essential: flow—a state of deep involvement in an activity that leads to a loss of self-consciousness—and meaning, which involves serving a purpose greater than oneself.

Still, one might find this answer unsatisfying. Why should these components make up true happiness? Seligman, for instance, does not explain why these aspects define happiness. Instead, he simply identifies these elements as part of happiness.3 Why accept this definition over others? Is there a coherent, unified framework for understanding happiness and its different facets? I believe there is.

Different types of hedonic signals

The mystery of happiness begins to dissipate if we consider that it is reasonable for our hedonic system to generate different types of hedonic signals. As I’ve argued before, our hedonic system can be understood as generating signals that guide our daily decisions, and it is designed to do this surprisingly well.

However, our decisions feature many dimensions to consider. It is therefore a good solution for our cognitive system to produce distinct values across different dimensions. For example, the positive feelings we experience from eating something good might not feel the same as the positive feelings we derive from feeling supported by friends. Both contribute to our life success in different ways, so it is unsurprising that they are encoded in different subjective feelings.

These various feelings are produced by different cognitive systems that process distinct types of information. Having various forms of positive and negative feelings can help us disentangle the factors influencing these emotions. If we are enjoying a good meal with a disgruntled friend, the appropriate actions will differ from those we should take if we were sharing a bad meal with a cheerful friend.

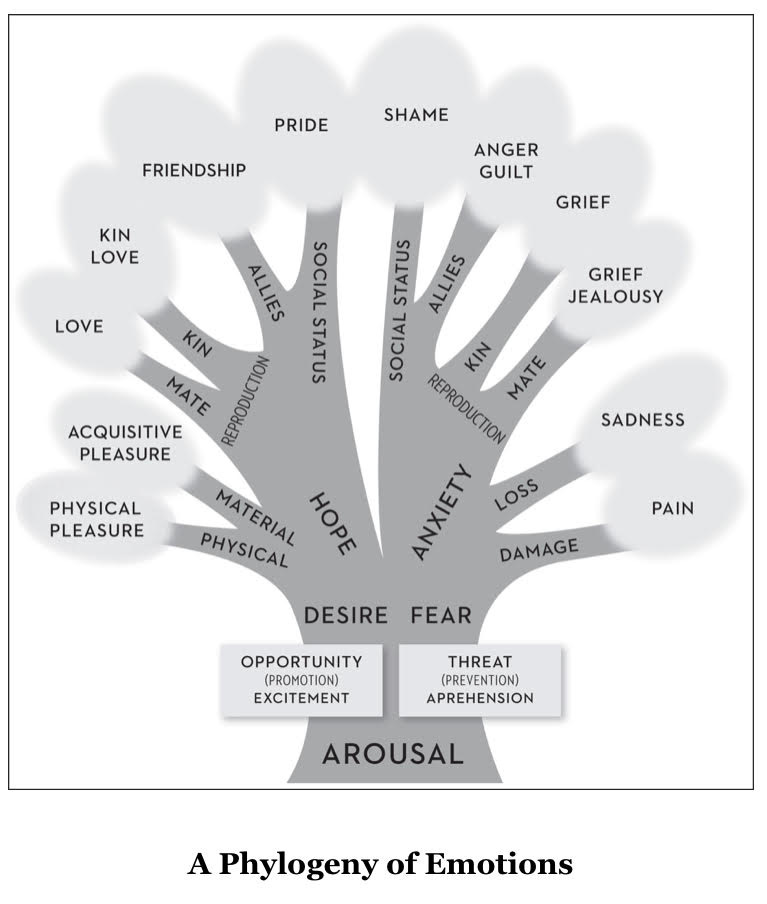

In his book Good Reasons for Bad Feelings, Randal Nesse identifies a range of positive and negative emotions that we may feel as a function of the outcomes we face in different settings: e.g. pleasure and pain in physical contexts, or pride and shame in social contexts. The feelings are the ingredients that blend into our overall perception of well-being.4

Different signals for different time scales

Time is one dimension in which different signals may be beneficial. While it’s useful for our brain to assess how well things are going right now, focusing solely on the present can prevent us from seeing the broader picture. Often, making sound decisions requires considering what we could achieve in the future if we were to change our behaviour now: a better education if we play fewer video games, a more caring partner if we invest time in relationships, or a more fulfilling career if we pursue new opportunities. To make such decisions, it is reasonable to have hedonic signals that assess our success over a time span beyond the immediate present.

Moods are an example of feelings designed for this purpose. They represent hedonic feelings that reflect our sense of how we’re faring in the current situation. Experiencing favourable circumstances that offer many opportunities might make us feel upbeat, motivating us to invest further in the situation. Conversely, inauspicious situations might dampen our mood, prompting us to consider alternative paths. Feelings of life satisfaction might be seen as extending this logic to large time spans, they work as hedonic stocktakes, integrating how we are doing overall in life.

In this light, it’s unsurprising to encounter conflicts between hedonic signals like pleasure and life satisfaction. Pleasures represent short-term hedonic signals of what is good in the moment, while feelings of life satisfaction represent long-term hedonic signals identifying situations that are likely to be good in the long run. Activities such as video gaming or consuming rich foods may provide pleasure, while also generating negative feelings as we recognise their conflict with broader life goals like achieving good grades or maintaining a healthy weight.

This possible conflict between feelings of life satisfaction and pleasure helps provide an answer to Robert Nozick’s experience machine paradox. Nozick proposed a thought experiment about a machine that could provide all the pleasurable feelings we might want for life. Once plugged in, we would experience any feeling we desired—becoming a famous actor, a successful influencer, or a sports star, without ever knowing we were in a machine. When asked if they would want to live in that machine, most people decline (De Brigard, 2010). Nozick argues that this is evidence against utilitarianism: that people desire more than just happiness.

An alternative explanation is that people’s responses reflect conflicting hedonic signals. On one hand, we may believe that being plugged in would feel good. Yet, we cannot help knowing that we would still be in the machine. Our system for assessing overall life satisfaction instinctively recognises that only experiencing artificial sensations generated in our brain would not constitute a successful life.5

A good life versus a pleasurable life

I believe that many beliefs of what makes a “good life” reflect our intuition about the inadequacy of mere pleasures to be the basis of a successful life.

Notably, a hedonistic pursuit of happiness is often associated with a lack of restraint. The pursuit of a higher form of happiness tends, instead, to be associated with a disciplined mind capable of controlling impulses.6 The negative view of hedonism can be understood as recognising that life success requires long-term planning and actions that may not be pleasurable in the short term.7

It is also interesting that many ideas about a good life relate to altruism and self-sacrifice. Aristotle described the eudaimonic aspect of happiness as rooted in a rational and virtuous life. Einstein is reported to have said, “Only a life lived for others is a life worthwhile,” and Martin Seligman defined a meaningful life as “using your signature strengths and virtues in the service of something much larger than you are.” In that view, a good life doing what is right. Chasing daily pleasures misses the deeper purpose of striving to be a good person.

A sceptical reader might question why this is the case. Why would happiness come from being virtuous? Is this belief simply wishful thinking, a comforting notion that the just find true happiness in a just world? History, unfortunately, is filled with examples of people who succeeded in life using non-virtuous ways and seemed unfazed by how their success was acquired.8

If one abandons, such moralistic wishful thinking, there remains a good reason to connect feelings of life satisfaction with more pro-social behaviours. Moral emotions likely evolved to help us navigate social interactions where gains from cooperation can be large if we adopt kind, though not naively altruistic, behaviour. The fairness norms in a society can be seen as equilibria of the social games of cooperation we play. In these interactions, goodwill, honesty, and helpfulness are rewarded by a positive reputation and greater opportunities for future cooperation

Hedonic feelings help us weigh the value of investing in our future by encouraging us to be good cooperators. Emotions like pride, shame, and guilt guide our decisions, countering the appeal of short-term selfish actions: should you take the last cookie (tempting!) or offer it to Alice, who hasn’t had one (thoughtful)? Similarly, when considering our lives in a broader context, we feel satisfied when we’ve successfully built a positive reputation as social cooperators and anticipate continuing to foster and enhance it.

The Aristotelian contrast between hedonic pleasure and virtuous eudaimonia can thus be seen as a conflict across time. Hedonism offers immediate pleasure, whereas aiming to have a good life leads to life conditions associated with long-term success: meaningful friendships, familial bonds, and social recognition at work.9

The secrets of happiness

It is not simple because trade-offs are everywhere

A lot of the self-help and happiness book industry is dedicated to helping readers find ways to be happy. Collectively, they offer a hodgepodge of often contradictory solutions: Should you strive for success or be content with what you have? Should you focus on building deep social connections or on becoming independent? Should you dedicate yourself to altruistic pursuits, or learn to say no and prioritise yourself?

This confusing landscape of advice becomes understandable once we recognise that our hedonic system is designed to manage complex trade-offs. We have many conflicting feelings, each pushing us toward balanced decisions. Advice about the “secrets of happiness” often zeroes in on one aspect, presenting it as though it holds a deeper meaning that outweighs others. The problem is that it ignores the trade-offs we always face. Let’s examine some of this contradictory advice about happiness.

Should you aim for success or be content with what you have? An optimal hedonic system induces you to have aspirations that are in line with what you can achieve. There is not much point in dreaming of an NBA career if one is 5’5 feet tall (1.65m). So, there is truth in the idea that setting overly ambitious goals leads to frustration. At the same time, success can bring a feeling of contentment, a sense of having done our best.

Should you prioritise building deep social connections or learn to be independent? Humans are a social species. Having social bonds with others in a solid social network that provides support and opportunities to cooperate is a critical factor for success. For that reason, we crave social connections and loneliness is a major driver of depression. But over-dependence on others has its own challenges; others don’t react well if you are overly demanding and needy. A balanced social life, then, requires us to avoid relying too heavily on others.

Should you invest yourself in altruistic endeavours or be willing to say no to others and put yourself first? Being a good social partner and having the reputation of being one is crucial for success. It fosters trust in others and helps us find social support. Thus, it is natural that we have a taste for pro-social actions, whether canvassing for a cause or baking for a school fundraiser. But pro-social behaviour cannot be unbounded. Someone who always says yes to others’ requests is bound to be taken advantage of. Therefore being able to say no is also essential.

In that light, statements of the form “the secret of happiness is…” are usually misguided. They might be intellectually appealing as they tap into intuitions about something that matters for happiness. However, they ignore the trade-offs one needs to take into account to make good decisions.

What to do

The perspective I propose here does not mean there is nothing to do. On the contrary. Much of life dissatisfaction results from evolutionary mismatches, where short-term hedonic signals (pleasure) conflict with long-term ones (contentment). There is real insight in Aristotle’s (and positive psychology’s) caution against chasing immediate pleasures. Being wary of these and mindful of long-term life goals is a good strategy to promote our long-term life satisfaction.

Investing in the future. An important cause of mismatch arises from the longer time horizon of our lives in modern societies. Life expectancy was still around 35 years in Europe in the 19th century.10 It is now more than double that. With a longer time horizon, investments in the future (like education and savings) become more beneficial. Institutions like banks also make investments in one’s future possible over a much longer time horizon than before. Yet, our hedonic system may not be adequately future-oriented, making it difficult to make choices that promote long-term satisfaction over short-term pleasures. Being able and willing to invest in one’s future is, for that reason, likely to have a positive effect on long-term life satisfaction.

Resisting present temptations. The cause of what we call present bias, the fact that we often tend to succumb to present temptations of pleasure instead of following a long-term plan likely reflects this evolutionary mismatch. Modern life makes this mismatch all the more challenging because it provides us with ways to “hack” our ancestral hedonic system: overindulgent food, video games, drugs, social media scrolling, and so on.11 Just as we might reject entering Nozick’s machine because we feel it would not be a life we want, we may want to avoid living our lives in what Baudelaire (1860) called artificial paradises.

Leveraging opportunities from cooperation. A neglected cause of mismatch is the fact that modern society is much safer and much less violent than past ones. As a consequence, we can benefit from much higher levels of cooperation.12 Our hedonic system may not be fully calibrated for this new situation. In the end, Aristotle may be right that being mindful of being virtuous might be a path to life satisfaction, at least in low-conflict and high-trust societies. In support of this idea, it has been found in countries as different as the USA and China that people who are seen as moral by others around them tend to state a greater sense of subjective well-being (Sun et al., 2024).13

Resisting the omnipresence of social comparisons. A further feature of modern life is the widespread opportunity for social comparisons that shape our life satisfaction. Economist Richard Layard (2005) argued that the spread of television has led people to overestimate the wealth of others, resulting in increased dissatisfaction. Social media has likely intensified the effect of social comparison by exposing us to curated glimpses of others’ wealthy lifestyles, and selected and carefully retouched images.14 Curating the media we consume and recognising the limited representativeness of what we see is a useful strategy to counteract these negative feelings.

Recognising that chasing long-lasting happiness is a pipe dream. Finally, there is one way to achieve greater life satisfaction that is not linked to an evolutionary mismatch. It is, paradoxically, to recognise that we were not designed to be happy and to chase happiness per se. Happy feelings are just incentives for us to make good decisions (from evolution’s point of view). Chasing happiness through a life of pleasures is in that perspective misguided. Long-lasting happiness will always be escaping us because of habituation. Being at peace with that fact may help avoid an endless pursuit of happiness that is doomed to fail.

Meaning of life?

A naturalistic explanation

The question of life satisfaction is often intertwined with that of life’s meaning. What, if anything, are we meant to do to make our lives meaningful? The answer depends on how “meaning” is defined. In practice, it seems that it often implies something transcendent, that gives sense to a life beyond that life itself. The term “bigger meaning” captures this idea.

When people speak of meaning, they often refer to contributing to a broader social good. I believe the feeling of meaning is an echo of our intuitions about what makes for a good life. These intuitions are shaped by our hedonic feelings. They associate positive feelings to having a successful family life, strong social connections and a high social standing in one’s community.

Some long-term goals can help progress in that direction, for example, guiding our children to grow up or helping our community to thrive. Having as a goal to achieve things that are recognised as good for one’s family or for one’s community and progressing towards that goal over time can feel meaningful for that reason. We feel content when we think we are moving in life in the right direction to achieve these goals. These experiences give us the feeling that our life is going somewhere. In that sense, meaning is a personal feeling, it is not something transcendent that makes a life more or less valuable for external reasons.

My approach here is obviously naturalistic. If you believe in metaphysical explanations (e.g. religion) then you could argue that some metaphysical principle gives life an external meaning. A naturalistic approach aims to resist the temptation of using skyhooks (Dennett, 1995), principles holding our conceptual framework from the sky. Instead, it aims to build explanations from the ground up. This is what I have done here, proposing that our feeling of meaning emerges as a product of our hedonic feelings about what is a good life, with these hedonic feelings having been shaped by evolution.

A useful metaphor

To gain some perspective on our feelings about the meaning of life, consider a metaphor. Imagine that, in a distant future, space engineers design a robot for a mission on another planet. Its task is to collect samples and conduct analyses, with the ultimate mission of forming a precise assessment of the planet’s habitability and the challenges of a potential settlement.

Because the engineers cannot predict the planet’s conditions precisely, they equip the robot with a value system that assigns higher value to actions aligned with its mission. This system allows the robot, “Bob,” to make its own decisions (e.g., when to collect samples or conduct analyses). As part of this system, the robot places value on activities such as recharging its battery in the sun (for survival) and making new discoveries (aligned with its mission).

Now, suppose the engineers decide to allow the robot to develop self-awareness but do not inform it of its overall mission and how it shaped its value system. Bob would be aware of the values he experiences, but not why he experiences them. He might then reflect on its activities, thinking, “I spend my days basking in the sun, collecting samples, and running analyses. Is this what gives my life meaning?”

In many ways, we are much like Bob: equipped with a hedonic system that guides our actions on this planet. This system works without requiring us to know how it was shaped—by evolution, a blind, impersonal process. It was not designed with any grand purpose for life or the universe. Our sense that certain actions give our lives “meaning” is a personal feeling; it doesn’t imply anything beyond that individual experience.

In an interview shortly before his passing, Daniel Kahneman—who dedicated the latter part of his career to studying happiness—shared a candid response to Peter Singer’s question about finding meaning in life.

Martin Seligman was trying to convince me that my life has meaning and his argument was that I could not have done what I had done if I thought that it was all meaningless and that comes back to the beginning of our conversation well you know, I can get up in the morning really eager to do my work and eager to solve a problem or to devise an experiment or to do whatever it was I was doing at the time without necessarily feeling that there is any higher objective [...] You are starting from a position where there is a general solution to what is good and I don't have that so I just don't follow you as far as I am concerned. [...] There isn't an objective point of view by which my life can be evaluated if you look at the universe and the complexity of the universe, what I do with my day cannot be relevant. - Kahneman15

While this perspective may sound bleak, recognising that feelings of happiness are signals designed to guide us in the world suggests that a sense of higher meaning is likely not essential to living well.16 Kahneman described himself as a “cheerful pessimist”. This term describes well someone whose pessimism about an overarching metaphysical meaning doesn’t prevent him from feeling cheerful and functioning well in everyday life.

The veil of mystery surrounding happiness and the meaning of life simply reflects our limited conscious understanding of what hedonic feelings are and how they function. These feelings are informative signals that guide our actions, selected over eons of evolution to help our ancestors survive and leave descendants.

The sense of living a “good life” and the contentment that comes from experiencing meaning are likely hedonic responses generated when we take a broader perspective beyond the immediate present. It makes sense to feel that “true happiness” cannot be found solely in short-term pleasure. Things like investing in one’s future, contributing to making one’s family grow and one’s community thrive can provide life satisfaction.

These feelings, however, are just that—signals produced by the brain to indicate whether we are on a path aligned with success, as calibrated by our ancestral past (which, of course, introduces some mismatches in the modern context). They do not imply a deeper, transcendent meaning. This may seem disheartening initially, as we often seek a bigger-picture justification for “doing the right thing.” Yet, these bigger-picture justifications are often not what drives our decisions. Ultimately, we can set aside the idea that there is an objective meaning of life or that we need to pursue it in order to find happiness.17

This is the before-last post in the series on happiness. In the final one, I will discuss the policy implications of this perspective on happiness. Does it make sense for public policy to aim to generate the greatest happiness in the population?

References

Aristotle, c. 350 BCE. Nicomachean Ethics.

Baudelaire, C., 1860. Les Paradis Artificiels. Paris: Poulet-Malassis et de Broise.

Bourdieu, P., 1979. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by R. Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

De Brigard, F., 2010. If you like it, does it matter if it's real?. Philosophical Psychology, 23(1), pp.43-57.

Dennett, D.C., 1995. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Fardouly, Jasmine, Phillippa C. Diedrichs, Lenny R. Vartanian and Emma Halliwell (2015) “Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood,” Body Image, Vol. 13, pp. 38–45.

Kant, I., 1785. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals.

Krasnova, Hanna, Helena Wenninger, Thomas Widjaja and Peter Buxmann (2013) “Envy on Facebook: A hidden threat to users’ life satisfaction?”, in Proceedings of the 11th International Conference onWirtschaftsinformatik (WI2013), Universität Leipzig, Germany, 27 February–3 January 2013

Kringelbach, M.L. and Berridge, K.C., 2010. The functional neuroanatomy of pleasure and happiness. Discovery medicine, 9(49), p.579.

Layard, R., 2005. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science. London: Penguin Press.

Madigan, J., 2015. Getting Gamers. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Nozick, R., 1974. Anarchy, State, and Utopia.

Nesse, R.M., 2019. Good reasons for bad feelings: Insights from the frontier of evolutionary psychiatry. Penguin.

Nettle, D., 2005. Happiness: The Science Behind Your Smile. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pinker, S., 1997. How the mind works. WW Norton&Company.

Plato, c. 375 BCE. The Republic.

Plato, c. 380 BCE. Gorgias.

Seligman, M.E., 2002. Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Simon and Schuster.

Sun, J., Wu, W., & Goodwin, G. (2024). Are moral people happier? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Forthcoming

The hypothetical imperative that represents the practical necessity of an action as a means to the promotion of happiness is assertoric. It may be set forth not merely as necessary to some uncertain, merely possible purpose but to a purpose that can be presupposed surely and a priori in the case of every human being, because it belongs to his essence. - Kant (1785)

The life of self-disciplined men is like that of the man who fills his jars, and when they are full he has enough and does not need to pour in more, and does not care about it anymore. But the life of undisciplined men is like the life of the man who is forced to keep on eternally filling leaky jars, under pain of extreme discomfort. - Plato

I have explained, in a previous post, how Seligman does not really define happiness. Instead, he offers what he thinks should be included in happiness. As pointed out by psychologist Daniel Nettle:

he muddles the waters with his definition […] if happines is defined to include activities that don’t make the actor feel good, who is to be the arbiter of whether they are “positive” or not? It looks like an evaluative moral framework is being smuggled in strapped to the underbelly of psychological science. - Nettle (2005)

Even though these feelings are produced by different cognitive systems, it makes nonetheless sense for them to be integrated and compared with each other by some brain processes in charge of making the right trade-offs when these feelings conflict. Recent evidence in neuroscience suggests hedonic feelings are all processed to some extent in the same brain area:

All pleasures from sensory pleasures and drugs of abuse to monetary, aesthetic, and musical delights would seem to involve the same fundamental hedonic brain systems. Pleasures important to happiness, such as socializing with friends, and related traits of positive hedonic mood are thus all likely to draw upon the same neurobiological roots that evolved for sensory pleasures. - Kringelbach and Berridge (2010)

Remember that these systems have been shaped to guide our actions toward fitness maximising actions, while an experience machine is not a scenario our sense would have been designed to handle, the vision of being inert forever in a machine might trigger negative feelings in terms of life satisfaction.

This judgment often has a social dimension, where physical pleasure is perceived as a pursuit for those of lower social standing. In The Republic, Plato opposes those enjoying pleasures and desires with those enjoying simple and moderate desires.

the manifold and complex pleasures and desires and pains are generally found in children and women and servants, and in the freemen so called who are of the lowest and more numerous class. […] Whereas the simple and moderate desires which follow reason, and are under the guidance of mind and true opinion, are to be found only in a few, and those the best born and best educated. - Plato

Sociologist Bourdieu (1979) is famous for having studied how the judgements of tastes are used to discriminate between social groups with privileged groups describing their pleasurable activities (opera, classical music, fine dining) as superior to lower class pleasure (popular movies, easy listening music, fast food).

Esop’s fable of The Ants & the Grasshopper provides a classical example of the danger of focusing on short-term pleasure. To the hedonic grasshopper who enjoyed summer and asks for food when winter arrives, the ants answer: "Making music, were you? […] Very well; now dance!"

In Plato’s Gorgias, the cynical and ambitious politician Callicles scoffs at Socrates' argument that a good life is rooted in virtue. Callicles, in a manner foreshadowing Nietzsche’s view that the strong should not be bound by moral rules designed to protect the weak, openly defends the idea that might makes right. Ultimately, Socrates is unable to convince Callicles through rational argument (even though it is, of course, a fictional debate crafted by Plato to give Socrates the upper hand!). Instead, Socrates concludes by warning Callicles that he will face consequences for his cynicism in the afterlife, where his soul will be judged by divine figures.

By “success” one has to understand “biological success”, that is fitness (surviving and having offspring). But two caveats need to be made, first people do not consciously aim for fitness, they are simply guided by their hedonic system to do things that increase their fitness. Second, our hedonic system was calibrated in an ancestral environment that was very different from the modern environment and it is likely to lead to evolutionary mismatches (footnote 11).

Modern life has both increased the availability and strength of pleasurable stimuli. Video games are designed by experts in behavioural science to hook as many as possible participants (Madigan, 2015) and modern food are abnormal stimuli as Pinker’s description of a cheesecake illustrates:

We enjoy strawberry cheesecake, but not because we evolved a taste for it. We evolved circuits that gave us trickles of enjoyment from the sweet taste of ripe fruit, the creamy mouth feel of fats and oils from nuts and meat, and the coolness of fresh water. Cheesecake packs a sensual wallop unlike anything in the natural world because it is a brew of megadoses of agreeable stimuli which we concocted for the express purpose of pressing our pleasure buttons. - Pinker (1997)

In a sense, it is a mechanical consequence of the fact that you are likely to interact with the same people over a much longer time span. In our ancestral past, a substantial number of conflicts might end up in ostracism or the death of one of the protagonists. An important result from game theory is that a longer horizon of mutual interactions can allow greater cooperative behaviour in the present. Even when interacting with different people, our past record of action follows us (e.g. CVs and references).

The sceptical reader may worry that I am smuggling back in a “just world” perspective, where true happiness is equated with being a good person. My point, however, is different: modern societies offer incentive structures that favour long-term strategies. With extended time horizons and greater rewards for sustained cooperation, a more pro-social attitude—one that may not be immediately prompted by our short-term inclinations—can, in expectation, lead to a more successful life in the long run. This does not exclude the possibility that some individuals may achieve success through cynical strategies, such as amassing wealth by betraying others or gaining political office through deception. Attempting to convince such people that they are not truly happy—much like Socrates’ attempt to persuade Callicles—would likely be futile. Instead, we should consider how society might structure incentives to make such behaviour less appealing as a life strategy.

I pointed out in Optimally Irrational (the book):

Facebook and other social media give people access to personal information from a wide network of people. This information is self-curated and, most often, positive. People post their beautiful (and carefully chosen) holiday pictures, and announce their positive news (promotion, engagement, awards). When exposed to such news and photos, people have regularly been found to experience negative feelings (Krasnova et al. 2013), and young women, in particular, can experience a lower mood and a greater dissatisfaction with their facial appearance (Fardouly et al. 2015).

In that same interview, he gave this insightful answer about his own research on life satisfaction and the feeling of meaning in life:

We ran a study to make a point on this, we asked people at the end of a day what was their best moment of their day, and we were thinking that if meaning is very important, then people would say that the most important moment of the day was a meaningful moment. It was actually a social moment, a moment they spent with somebody else, happily. There was no mention of transcendental experiences. That's very rare. So when you start thinking about it, putting diapers on a baby is a meaningful experience but when you are doing it, most of the time it is not a meaningful experience. Meaning is something that comes up when people ask themselves about meaning. That is my view. It is disproportionately important when you evaluate your life so when you evaluate your life, the question of whether your life has meaning looms quite large.

Evolution does not need us to hold beliefs in a higher meaning to make good decisions. Instead, these beliefs probably arise as a by-product of our advanced cognitive abilities and our efforts to interpret our hedonic feelings. As a consequence, our hedonic feelings (e.g. life satisfaction) are likely not dependent on whether we hold these beliefs or not.

I cannot help quoting here the simple wisdom of Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life:

Now here's the Meaning of Life. […] Well, it's nothing special. Try and be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in and try and live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations.

This series has been most helpful in providing a frame of reference which other life advice can be related to and analysed through (such as the conflicting advice found in self help books you mention). I was happily suprised that the complex information I was looking for was provided through enjoyable metaphors, easy to follow trains of thought and clear descriptions in your articles.

I'm happy Chris Wiliamson recommended your substack.

Thoughts related to what can be deemed important and/or worthwhile pursuits has been on my mind quite a lot the past few years, and this has provided much-needed clarity for me.

Fascinating, helpful and thought provoking, thank you! I kept thinking about the price of non-conformity which obviously has evolutionary disadvantages. If you want to stay alive, you don't piss off your tribe. But isn't the pursuit of truth a higher ideal (kind of sky hook?) that can bring a sense of purpose and contribute to happiness? Science and human progress depend on people like Galileo insisting that facts are real (Eppur si muove!) even when the social group forces them to say otherwise.

The question of whether principled non conformity is worth the social cost seems especially timely now with communities, families and friends being torn apart by political differences. It's definitely real to me personally since social justice dogmatism took over my social circles and workplace. What would Socrates say?