Everything is relative... to others

How social comparisons shape our subjective satisfaction

The 13th-century Persian poet Saadi Shirazi described how social comparisons shape our subjective satisfaction in a way that has become famous:

I cried because I had no shoes, until I met a man who had no feet. - Saadi Shirazi (1258)1

We often assume that our life goals are defined by objective standards of comfort and aspiration, like having a good job and a happy family. Yet Saadi’s story encapsulates a simple truth: Our happiness largely depends on how our circumstances compare to those of others.

The social science of social comparison

The readers of this Substack know that I like the history of ideas. So let’s start with a brief history of the science of social comparison. With the rise of social sciences in the 20th century, the idea that we compare ourselves to others began to be studied systematically across sociology, psychology and economics.

Economics: People care about their relative income…

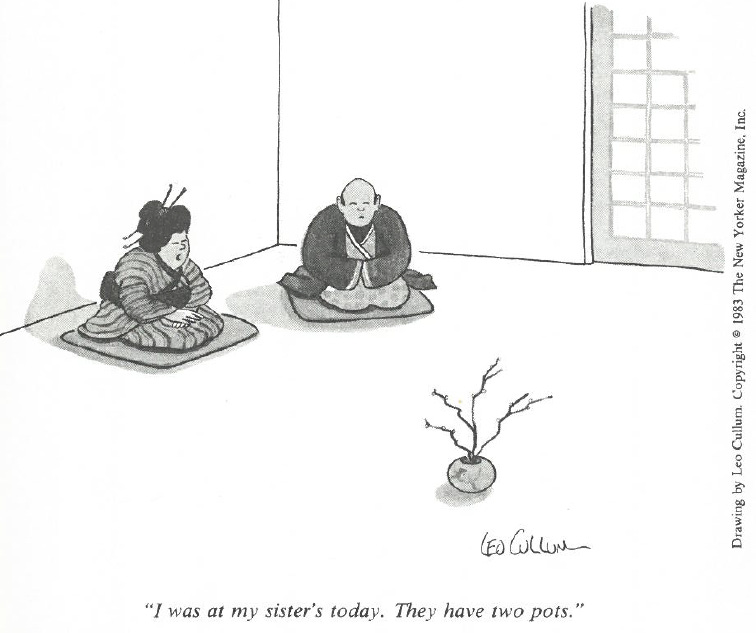

In his classic book on conspicuous consumption and social status, The Theory of the Leisure Class, Veblen emphasised the concerns for relative economic success:

The end sought by accumulation is to rank high in comparison with the rest of the community in point of pecuniary strength. So long as the comparison is distinctly unfavourable to himself, the normal, average individual will live in chronic dissatisfaction with his present lot. - Veblen (1899)

Economist Duesenberry argued, in his 1949 book, Income, Saving and the Theory of Consumer Behavior, that people’s concerns for how their income compares to others have an impact not only on their satisfaction but also on their consumption and saving decisions. This idea became known as the relative income hypothesis.

Sociology: …compared to a reference group…

Sociologists went beyond this observation and pointed out that when assessing our life achievements, we tend to compare ourselves to specific people. In his book The Psychology of Status (1942), Herbert Hyman proposed the term “reference group” to describe the people we compare to. Later, Robert Merton built on Hyman’s work to define reference group theory:

The theory of reference groups and relative deprivation starts with the simple idea, […] that people take the standards of significant others as a basis for self-appraisal and evaluation. - Merton (1957)

He noted, however, a lack of understanding of how these reference groups are formed.2

Psychology: … whose members look like you

A few years earlier, the psychologist Festinger had proposed a related theory, social comparison theory offering a possible answer to how reference groups are selected. In a highly cited paper,3 he suggested that people use others as a reference due to a drive to “self-evaluate”. In this perspective, the natural reference groups are those with people similar to us.

There exists, in the human organism, a drive to evaluate his opinions and his abilities. […] To the extent that objective, non-social means are not available, people evaluate their opinions and abilities by comparison respectively with the opinions and abilities of others. […] The tendency to compare oneself with some other specific person decreases as the difference between his opinion or ability and one' s own increases. - Festinger (1954)

Bertrand Russell had already succinctly expressed this idea in The Conquest of Happiness:

Beggars do not envy millionaires, though of course they will envy other beggars who are more successful. - Russell (1930)

The evidence about social comparisons

The evidence for social comparison is pervasive, and economists now study its role in life satisfaction and economic decisions.4 A compelling example is a study on lottery winners in the Netherlands. When individuals won luxury cars (BMWs) as prizes, car purchases increased in their surrounding neighbourhoods (Kuhn et al. 2011).5

However, social scientists remain often uncertain about how reference groups are selected. In a survey on happiness economics, Ada Ferrer-i-Carbonell wrote:

The way in which individuals form their reference groups […] is not yet understood. - Ferrer-i-Carbonell (2013)

In Optimally Irrational (the book), I argued that integrating the evidence across behavioural sciences provides a good explanation of how reference groups are determined. There are two types of reasons why we care about others’ achievements when assessing our own.

The two reasons we care about relative comparisons

Information

First, others’ achievements inform us about our potential. As discussed in this previous post, our hedonic system is designed not just for us to make good decisions but for us to make the best decisions possible. Our peers provide valuable information in this context. In a recent paper, we argue that we should use peers as a comparison group to the extent that they are informative to set our aspirations (Kubitz and Page, 2024). We confirm Festinger’s idea that we compare ourselves to similar others, but not because of a drive to self-evaluate. Rather, our self-evaluation is critical for calibrating our aspirations and identifying the range of outcomes we should aim for.

The first reason why peers’ achievements are informative is that they can reveal something about our future opportunities. Albert Hirschman famously illustrated this idea with a traffic jam metaphor:

Suppose that I drive through a two-lane tunnel, both lanes going in the same direction, and run into a serious traffic jam. No car moves in either lane as far as I can see (which is not very far). I am in the left lane and feel dejected. After a while the cars in the right lane begin to move. Naturally, my spirits lift considerably, for I know that the jam has been broken and that my lane's turn to move will surely come any moment now. - Hirschman and Rothschild (1973)

The second reason is that others’ achievements can provide feedback about our past and current choices. We learn from our peers what could have been if we had made different decisions.6 This effect on our happiness tends to be negative when we observe others doing better than us. In Hirshman’s example, if you see the other lane moving, you may become frustrated not to have switched lanes earlier.

Suppose that you find out on social media, the professional outcome of an old classmate who had similar grades as you at school. This classmate took a job abroad that you thought was risky, while you opted for a secure local job. Let’s consider two scenarios:

Scenario 1. Your classmate’s decision was highly successful, leading to rapid career progression and a much higher salary than yours.

Scenario 2. Your classmate’s decision proved unfortunate, resulting in disappointing career evolution and frustration from being far from family and friends.

In the first scenario, you might feel that you could have done better, that your choice was too conservative. In the second, you might feel vindicated for resisting a risky career abroad. A hedonic system reacting to such information helps us make better decisions, either by reinforcing successful choices or encouraging changes when we are not doing as well as others.

Competition

We do not just care about social comparison for the sake of information. We also care about our social status, a social value granted to us by others (Storr 2021). Status is inherently valuable as it leads to greater access to resources and partnerships. Psychologist David Buss noted:

Social status is a universal cue to the control of resources. Along with status come better food, more abundant territory, and superior health care. […] In one study of 186 societies ranging from the Mbuti Pygmies of Africa to the Aleut Eskimos, high-status men invariably had greater wealth and more wives and provided better nourishment for their children. - Buss (2015)

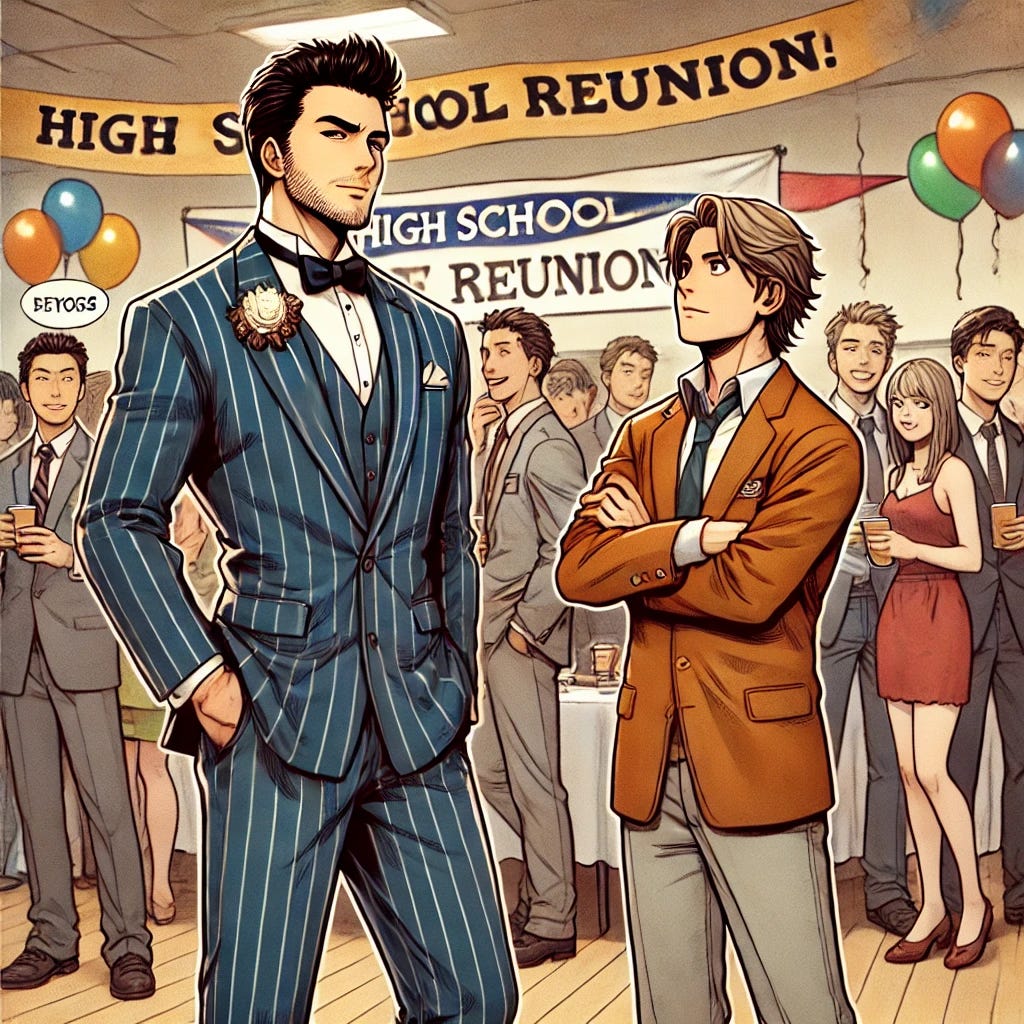

We should therefore expect our hedonic system to associate positive emotions with status rises and negative emotions with status decreases. Importantly, our status reflects our position in a social ranking and is always relative to others. Others’ success in our close social circles impacts our well-being for this reason too. Consider a third scenario about your classmate’s success:

Scenario 3. Your classmate’s decision was highly successful, leading to rapid career progression and a much higher salary than yours. Now your classmate is returning to settle in your city.

Here, your old classmate’s success isn’t just abstract information. Back in your local social circle, your classmate’s success may outshine yours. You might already feel less enthusiastic about the upcoming 10-year class reunion.

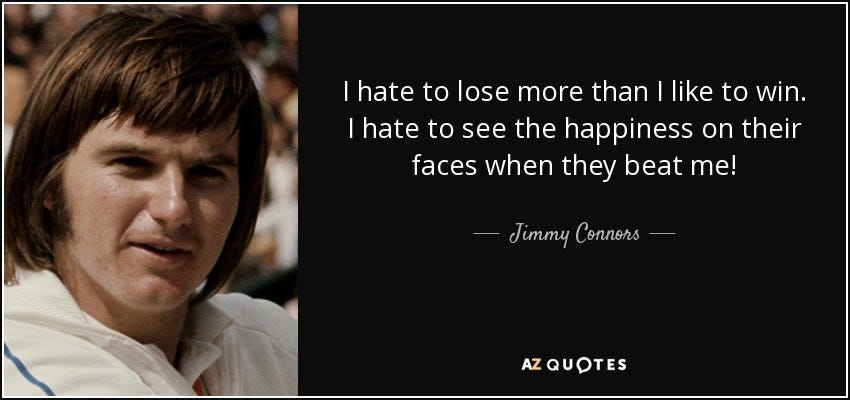

These competitive feelings explain spiteful behaviour, where people are sometimes willing to incur costs to lower the standing of others. In his book Spite, psychologist Simon McCarthy Jones pointed out that some of our emotions are designed to nudge towards reducing others’ advantages.

Emotions, such as envy (displeasure at another’s gain) and schadenfreude (pleasure at another’s loss), can […] drive us to undertake spiteful actions. - McCarthy Jones (2021)

The game theory of contests shows that concerns for relative standing may increase conflict in competitive environments, leading people to invest more effort and resources, not just to win but also to prevent others from winning (Konrad, 2009).

Our multifaceted reactions to others' achievements

In addition to the feelings we experience from social comparison, we also experience positive emotions when we observe success in our friends, partners, and in-group members. Feeling supportive of people we are close to is part of the psychological architecture that supports sustained cooperation. This is even more evident in situations where we can indirectly benefit from others’ success, like when we are on the same team. An individual succeeding in our team can be a champion for us all, like a colleague securing a deal for our company or an athlete winning a medal for our country.

When we see others succeed, we can experience a blend of complex emotions: When your colleague achieves something significant, you might feel both happy for your company and frustrated that his status is rising relative to yours in the office. When your friend announces her child’s acceptance into a prestigious school, you might feel happy for her while also stinging from the feeling that you could have done better for your own child who did not pursue the same path.

This blend of emotions reflects the different meanings and implications for us of others’ success: positive feelings when we realise that the same path to success may be available to us, negative feelings when we learn we could have performed better, negative emotions stemming from status competition, and positive feelings towards the success of friends and fellow team members.

This post is part of a series on the psychology of happiness. In the previous posts, I have looked at what happiness is, why we are averse to losses, and why we give ourselves high goals and aspirations that are hard to reach.

References

Buss, D., 2015. Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind. Routledge.

Clark, A.E., Frijters, P. and Shields, M.A., 2008. Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), pp.95-144.

Duesenberry, J.S., 1949. Income, Saving and the Theory of Consumer Behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., 2013. Happiness economics. SERIEs, 4(1), pp.35-60.

Festinger, L., 1954. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), pp.117–140.

Hirschman, A.O. and Rothschild, M., 1973. The changing tolerance for income inequality in the course of economic development: With a mathematical appendix. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(4), pp.544-566.

Hyman, H.H., 1942. The psychology of status. Archives of Psychology (Columbia University).

Konrad, K.A., 2009. Strategy and dynamics in contests. Oxford University Press.

Kubitz, G. and Page, L., 2024. “If you can, you must.” Information, utility, and loss aversion.

Kuhn, P., Kooreman, P., Soetevent, A. and Kapteyn, A., 2011. The effects of lottery prizes on winners and their neighbors: Evidence from the Dutch postcode lottery. American Economic Review, 101(5), pp.2226-2247.

McCarthy-Jones, S., 2021. Spite: The Upside of Your Dark Side. Basic Books.

Merton, R. K., 1957. Continuities in the Theory of Reference Groups and Social Structure. In: R. K. Merton, ed. Social Theory and Social Structure. Rev. ed. Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press, Chap. IX.

Page, L., 2022. Optimally irrational: The good reasons we behave the way we do. Cambridge University Press.

Russell, B. (1930). The Conquest of Happiness. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Sherif, M., and Sherif C., 1956. An outline of social psychology. Harper

Storr, W., 2021. The Status Game: On Social Position and How We Use It. London: William Collins.

Veblen, T., 1899. The Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Macmillan.

This quote is the usual way the following passage in his collection of poems, The Rose Garden (1258), is summarised: “I never complained at the vicissitudes of fortune, nor murmured at the ordinances of Heaven, excepting once, when my feet were bare, and I had not the means of procuring myself shoes. I entered the great mosque at Cufah with a heavy heart when I beheld a man who had no feet. I offered up praise and thanksgiving to God for his bounty, and bore with patience the want of shoes” (ch. 3, Tale 19). This quote is nowadays often attributed to modern personalities.

Under which conditions are associates within one's own groups taken as a frame of reference for self-evaluation and attitude formation, and under which conditions do out-groups or non-membership groups provide the significant frame of reference? Reference groups are, in principle, almost innumerable. - Merton (1957)

Festinger’s paper currently has 34,000 citations on Google Scholar.

Despite all these theories, social comparison was not commonly adopted in economics until recently. Standard models assumed people are self-centred and care about their own material situation. As late as 2008, economists Clark, Frijters, and Shields stated that “taking relative income seriously is an important step toward greater behavioral realism in Economics”. However, the role of social comparisons in subjective satisfaction is now fully accepted in economics.

Evidence of “keeping up with the Joneses” isn’t new. Muzafer and Carolyn Sherif recounted in 1956:

In many companies executives continuously play the game of “one-upmanship,” the gentle art of being a jump ahead of colleagues in acquiring everything from better ashtrays to air conditioners. In general, the president and board chairman, who get the best of everything anyway, are rarely involved; the struggle takes place among the vice presidents, and below. A few years ago, a Dallas company set up a new subsidiary with five brand-new vice presidents installed in identical offices. Everything was peaceful until one used his expense account to replace his single-pen set with a two-pen set. Within four days all five worked their way up to three-pen sets. - Sherif and Sherif (1956)

Hirschman’s example continues with a description of frustration:

But suppose that the expectation is disappointed and only the right lane keeps moving: in that case I, along with my left lane cosufferers, shall suspect foul play, and many of us will at some point become quite furious and ready to correct manifest injustice by taking direct action (such as illegally crossing the double line separating the two lanes). - Hirschman and Rothschild (1973)

Note that while the paper is co-authored by Albert Hirschman and Michael Rothschild, the latter is only credited for the mathematical appendix in the paper and the quote is usually attributed only to Albert Hirschman.

Great post as usual, Lionel. I hadn’t considered that there are also epistemic benefits to social comparison (gaining knowledge about what’s possible for me to achieve) independent of status concerns—that’s a good insight. But it still leaves the puzzle unsolved as to how we determine the reference group. It seems like the optimal way to choose a reference group—at least to fulfill the epistemic function—is to select people who are as similar as possible on whatever dimensions are most causally relevant to achieving the goal in question. We may even have different reference groups for different goals. I may not care if my tennis equal (in terms of skill level), gets a promotion at his job, but it stings if he wins a tournament and I don’t. So there may not be one, singular reference group, but it may be tailored to the specific goal under consideration, focusing on whatever variables are most relevant for the achievement of that goal.

Informative read, Lionel! I'm always quietly frustrated with myself when I notice envy creeping up within me. Siblings being treated differently, Boomers effortlessly owning multiple properties, people my age "affording" 5k/mo apartments. It's true, some of these comparisons can serve to guide our decisions to better outcomes, I've also found a lot more peace from turning inward and comparing myself to - well, my previous self. My life now is a dream I once had, and for that I am grateful.