Explaining loss aversion

It's not a bug, it's a feature designed to help us make good decisions

This post is the first in a series on the psychology of happiness. Co-written with Greg Kubitz, we discuss the results of a recently released paper where we show that loss aversion may be thought of as a feature of our cognition that helps us make good decisions.

In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman stated: “The concept of loss aversion is certainly the most significant contribution of psychology to behavioral economics.” Loss aversion is the fact that, subjectively, losing feels worse than winning feels good. The idea has been expressed throughout human history. It can be found, for instance, in Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments:

Adversity, …, necessarily depresses the mind of the sufferer much more below its natural state, than prosperity can elevate him above it. - Smith, Theory of Moral Sentiments, Book I. Chapter iii

Kahneman and Tversky’s Prospect Theory

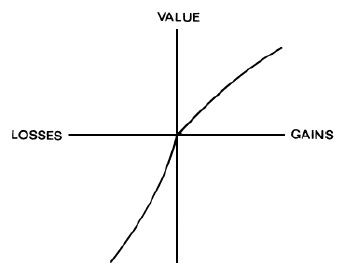

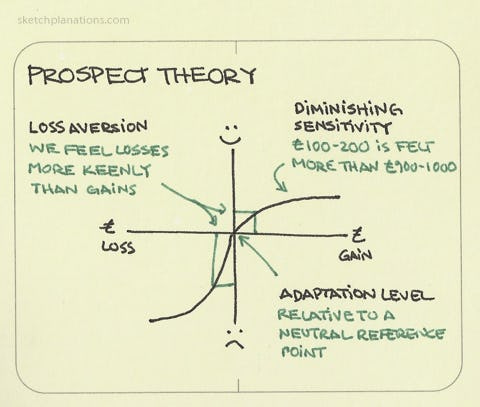

Kahneman and Tversky studied this psychological pattern carefully and convinced economists to include it in their models. Loss aversion is one of the three pillars of Prospect Theory which posits that subjective satisfaction is relative to a subjective benchmark, a reference point. When we consider a given outcome, if it is above our reference point, we feel gains; if it is below, we feel losses.

What is this reference point? In their 1979 article, Kahneman and Tversky focused on actual losses and gains relative to one’s current situation. But they also stressed that a reference point can differ from the status quo. It can be an aspiration level:

There are situations in which gains and losses are coded relative to an expectation or aspiration level that differs from the status quo. - Kahneman and Tversky (1979)

Loss aversion is typically included in the list of cognitive biases. In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman discusses its “paralyzing effects” on decision-making and how experimental participants can be “cured” of it.

Explaining the features of subjective satisfaction

One idea defended on this Substack is that there are often good reasons behind features of human cognition described as “biases”. Humans are the product of a long evolutionary process. If we observe a surprising aspect of human cognition, it makes sense to ask whether there could be a good reason behind it, before dismissing it as an error. This approach has been called reverse engineering: looking for the causes that may have generated the features of our human psychology.

At its core, the discovery of the design of human psychology and physiology is a problem in reverse engineering. - Tooby and Cosmides (1992)1

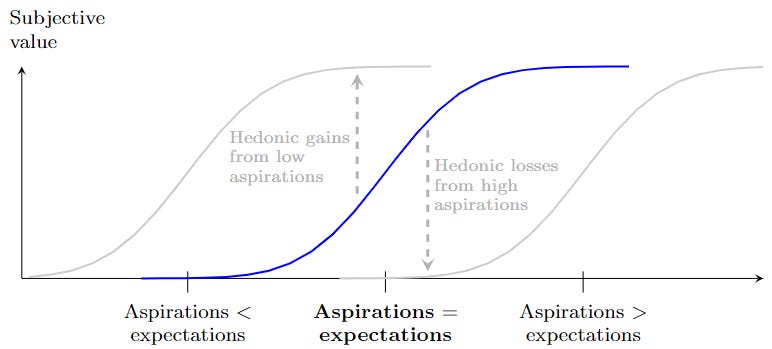

This approach has been used in economics to explain the origin of economic preferences (Robson and Samuelson, 2011). In a post last year, Lionel explained that the features of subjective satisfaction identified by Prospect Theory can be described as adaptive: they help us make good decisions.2 In that perspective, our reference point should be set at the level of our expectations. This way, our subjective satisfaction is more sensitive to small variations in outcomes in the range we are most likely to encounter.

Economists Arthur Robson (2001), Luis Rayo and Gary Becker (2007) and Nick Netzer (2009) have provided formal backing to this intuition showing that an optimal subjective satisfaction system should somewhat follow the distribution of the values we face. Specifically, our subjective satisfaction should follow a subjective value function whose curve is S-shaped with an inflection point in the middle like the reference point in Prospect Theory. The curve is steepest around our expectations. It is represented in the figure below.

These features sharpen our perception of the value of small differences in outcomes in the range we are most likely to face. Consequently, they help us make good decisions more frequently.3

Consider the following scenario. Alice, Bob and Candice all work in the same company. They are considering asking for a raise, and, from past evidence, it seems that they could expect a raise of around 10%. They have different reference points. Alice aspires to get 10% while Bob has low aspirations, any raise would be good for him. Finally, Candice has very high aspirations, wanting 20%. Anything below and she will be frustrated about the outcome.

Given that the actual range of best offers they can get is likely around 10%, who do you think will do better in the negotiation? Let’s say they all get a first offer of 5%. Out of the three, Alice cares the most about the difference between 5% and 10%. She is likely to spend time and effort thinking about how she could make the best case to get 10%. In comparison, both Bob and Candice care less about an additional 5%. Bob is already happy with the initial 5%, and Candice will still be frustrated with 10%. Alice’s well-calibrated aspirations help her because she cares about getting the best outcome in the range where she is most likely to have to make decisions.

In this explanation, of the adaptive nature of the subjective value function, one ingredient from Prospect Theory is missing: loss aversion. In a paper we just released, we show that there are also good reasons to think that loss aversion has an adaptive role.

Agency

The starting point of our explanation is a challenge raised by Prospect Theory: if our satisfaction is relative to a reference point that acts as an aspiration level, why don’t we decide to have low aspirations? The idea that low aspirations are the secret to happiness was already expressed by ancient philosophers like Laozi (6th century BC) and Epictetus (2nd century AD).4

The adaptive explanation suggested earlier states that the best location of the reference point to make good decisions is at the level of expectations. However, what if people can choose to have aspirations below their expectations? What if, as suggested by research in psychology and our intuition, people are, to some extent, able to “manage their expectations” to avoid disappointment? Psychologists have found that, when waiting for important news, people often engage in defensive pessimism.

Several decades of research support the benefits of lowering one’s expectations at the moment of truth to brace for the worst and minimize the blow of bad news. - Sweeny (2018).

The gains from low aspirations are illustrated in the figure below. Suppose you have average expectations about your future success in a given project. You may choose to set aspirations around your expectations, higher than that, or lower than that. An optimal choice to make you good at discriminating the outcomes you face would be to set your aspiration level around your expectations.

If you decide to have lower aspirations—i.e. you get the left curve—you will always feel better because whatever you get you’ll judge it with a lower benchmark. Most outcomes will give you a level of satisfaction towards the top of the range of satisfactions you could experience. On the contrary, high aspirations—i.e. you get the right curve—are costly in terms of subjective satisfaction. Most of the outcomes will be associated with a low level of subjective satisfaction.

In our example, with no particular aspirations about a raise (a reference point at 0%), Bob is guaranteed not to be disappointed with the outcome. Any raise will feel good.

Preventing overly low or overly high aspirations

The fact that we seem to have some agency when we set our aspirations is a problem for our subjective satisfaction system. To prevent low aspirations, our subjective satisfaction could provide us with some satisfaction for setting high aspirations in the first place. Indeed, it does exactly this. When you get good news about your prospects, you get elated and raise your aspirations. Economists have called this anticipatory utility: the subjective satisfaction you experience from anticipating good outcomes in the future (Loewenstein, 1987).

While you may be tempted to keep low aspirations, anticipatory utility compensates for that by making you feel good now about the possible things you may achieve tomorrow. In our example, Alice may be disappointed if she does not get a raise. But when she thought about it and considered she had a good chance of getting one, she felt good about the prospect.

So that’s it, isn’t it? The problem of miscalibrated aspirations is solved! Not really, because feeling good about having high aspirations may lead to another problem—wishful thinking—when we bask in the good feelings of aspirations that are too high. In our example, Candice may enjoy the idea that she could get 20% too much, leading her to set aspirations above her expectations.

An optimal system of subjective satisfaction therefore needs to provide the right balance between two possible miscalibrations of aspirations: defensive pessimism and wishful thinking. What we show in our study, is that a system of subjective satisfaction that features loss aversion provides the right incentives to set our aspirations at the level of our expectations.5

To incentivise us to set our aspirations correctly, the optimal subjective satisfaction function bulges upward around its middle part. That feature has two simple consequences: First, it reduces the hedonic gains from low aspirations. It does not pay as much to have low aspirations because you already feel very good from having the correct aspirations and reaching them. Second, it increases the cost of high aspirations. Since you have high levels of satisfaction from reaching your aspirations, it is more costly to set higher aspirations that you are likely to fail to reach.

The consequence of this distortion of the subjective value function is that it is not symmetric anymore around the level of aspirations. It exhibits a steeper drop below than a rise above it. These characteristics are what’s called loss aversion. What we showed in our paper is that loss aversion features as part of an optimal system of subjective well-being.6

The fact that the optimal subjective value function bulges up around the level of expectations can be interpreted as rewarding people for choosing an aspiration that corresponds to their expectations. It fits with observations from psychology that the baseline level of subjective satisfaction people experience around their expectations is not neutral but positive (Diener et al., 2009).

What about the kink?

Loss aversion has traditionally been presented as inducing a kink in the subjective value function at the reference point. This feature is notably absent from our result.

The first point we can make is that a kink has never been a result of the empirical study of subjective value. Rather it is implied mechanically by the assumption that the value function is composed of two parts, one for the gains and one for the losses with the part in the losses having a steeper slope. The kink is a property of the limit of the slopes on the right and left sides of the reference point. As a consequence, it is, in practice, impossible to test empirically.

The kink has become a canonical part of Prospect Theory. But we do not see it as a necessity. Instead, we can think of the assumptions made by Kahneman and Tversky as “working” to describe the available data. The figure below shows our solution featuring loss aversion with Kahneman and Tversky’s 1979 solution superimposed onto it. The assumption of a piecewise function around the reference point, with a kink at the reference point provides a close approximation of our solution.

Loss aversion is typically seen as a behavioural bias. What we have shown here is that it can instead be thought of as a feature of an optimal system of subjective satisfaction designed to use our knowledge about the likely outcomes we may face to set our aspirations around our expectations.

In an interview given to Peter Singer, shortly before he passed away, Kahneman said with incredible humility:

I expect everything that I have done to be overwritten. It's nothing of eternal value. I am surprised that the work that Amos and I did has survived for half a century. That's remarkable. [...] I am seeing that happen. I am old enough and seeing the beginning of the overwriting. The future is going to be different. There is going to be, it seems in psychology, a return to rationality. - Kahneman

Kahneman was too harsh using the word “over-written”. Instead, the modern convergence of economic theory and cognitive neuroscience is shaping a rewriting of Kahneman and Tversky’s insights into a conceptual framework that explains them as adaptive. We see our work on loss aversion, which builds on the previous works by Robson, Rayo and Becker and Netzer, as contributing to such an enterprise.

References

Agassi, A. (2009). Open: An Autobiography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Arrow, K.J., 1984. The economics of agency.

Dennett, D.C., 1990. The interpretation of texts, people and other artifacts. Philosophy and phenomenological research, 50, pp.177-194.

Diener, E., Lucas, R.E. and Scollon, C.N., 2009. Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. The science of well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener, pp.103-118.

Epictetus, 2nd century AD. The Enchiridion.

Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A., 1979. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), pp.263-291.

Kahneman, D., 2011. Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Kubitz, G., and Page, L., 2024. “If you can you must.” Information, utility and loss aversion. Working paper

Laozi, 6th century BC. Tao Te Ching.

Loewenstein, G., 1987. Anticipation and the valuation of delayed consumption. The Economic Journal, 97(387), pp.666-684.

Netzer, N., 2009. Evolution of time preferences and attitudes toward risk. American Economic Review, 99(3), pp.937-955.

Rayo, L. and Becker, G.S., 2007. Evolutionary efficiency and happiness. Journal of Political Economy, 115(2), pp.302-337.

Robson, A.J., 2001. The biological basis of economic behavior. Journal of Economic Literature, 39(1), pp.11-33.

Robson, A.J. and Samuelson, L., 2011. The evolutionary foundations of preferences. Handbook of Social Economics, 1, pp.221-310.

Sweeny, K., 2018. On the experience of awaiting uncertain news. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(4), pp.281-285.

Tooby, J. and Cosmides, L., 1992. The psychological foundations of culture. The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture, 19(1), pp.1-136.

The idea of evolutionary psychology as a process of reverse engineering was suggested earlier by Dennett (1990).

That post, which attracted significant interest at the time, explained the general “S-shape” of subjective satisfaction around a reference point. It ended with the following words: “loss aversion? That... is a topic for another post.” This other post is the present one!

Our subjective perception of the value of the possible outcomes we face is not perfectly precise, making outcomes that are close in value feel similar.

Laozi’s quote is from the Tao Te Ching and Epictetus wrote in The Enchiridion:

Demand not that things happen as you wish, but wish them to happen as they do, and you will go on well. - Epictetus

For the technical readers: We model evolution using a mechanism design approach, following Rayo and Becker (2007). We ask: What is the best subjective satisfaction system evolution could design for optimal decision-making? Previous works (Robson, 2001; Rayo and Becker, 2007; Netzer, 2009) considered biological constraints. We add informational constraints: the agent has hidden information about his expectations in specific contexts. It is a principal-agent problem with hidden information (Arrow, 1984). Section 2 of our paper presents an intuitive explanation of why loss aversion emerges as a solution of this problem.

This explanation differs from Kahneman’s own evolutionary explanation: loss aversion exists because threats are more dangerous than opportunities are beneficial:

This asymmetry between the power of positive and negative expectations or experiences has an evolutionary history. Organisms that treat threats as more urgent than opportunities have a better chance to survive and reproduce. - Kahneman (2011)

This idea, while intuitive, has not been formally theorised, it seems. We agree organisms must prioritise survival threats, but this does not fully explain loss aversion as described in Prospect Theory.

For instance, Prospect Theory assumes diminishing sensitivity to increasing losses, while a “threat’ explanation might suggest increasing sensitivity. Also, loss aversion applies to high aspiration levels. Former number 1 tennis player Andre Agassi wrote about his experience of winning his first slam:

Now that I’ve won a slam, I know something that very few people on earth are permitted to know. A win doesn’t feel as good as a loss feels bad, and the good feeling doesn’t last as long as the bad. Not even close. - Agassi (2009)

The “threat” explanation doesn’t provide an intuitive explanation for loss aversion at high levels of outcomes.

It’s really interesting. Your visualisation of the curve makes it intuitive to see the goal as a trajectory & this got me reading about the principle of least action. The curve made me think about energy in motion & I realised that you could see loss aversion as an adaptation to overcome inertia to set the system (goal seeking) in motion. Once the system is in motion, the energy input needed will quickly decay past a certain reference point. Hence the kink/inflection. You can see it in the trajectory of a ball that has a shallow rounded curve on the upwards journey & then a steep decay as a reference point is passed. We intuitively seek the path of least action & rule out paths that would impede our success (too much aspiration or too much anxiety).

Thanks. Very interesting article.

Have you seen this article?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7538829/