Not Another Bias!

We have uncovered enough behavioural biases. It's time to understand where they come from.

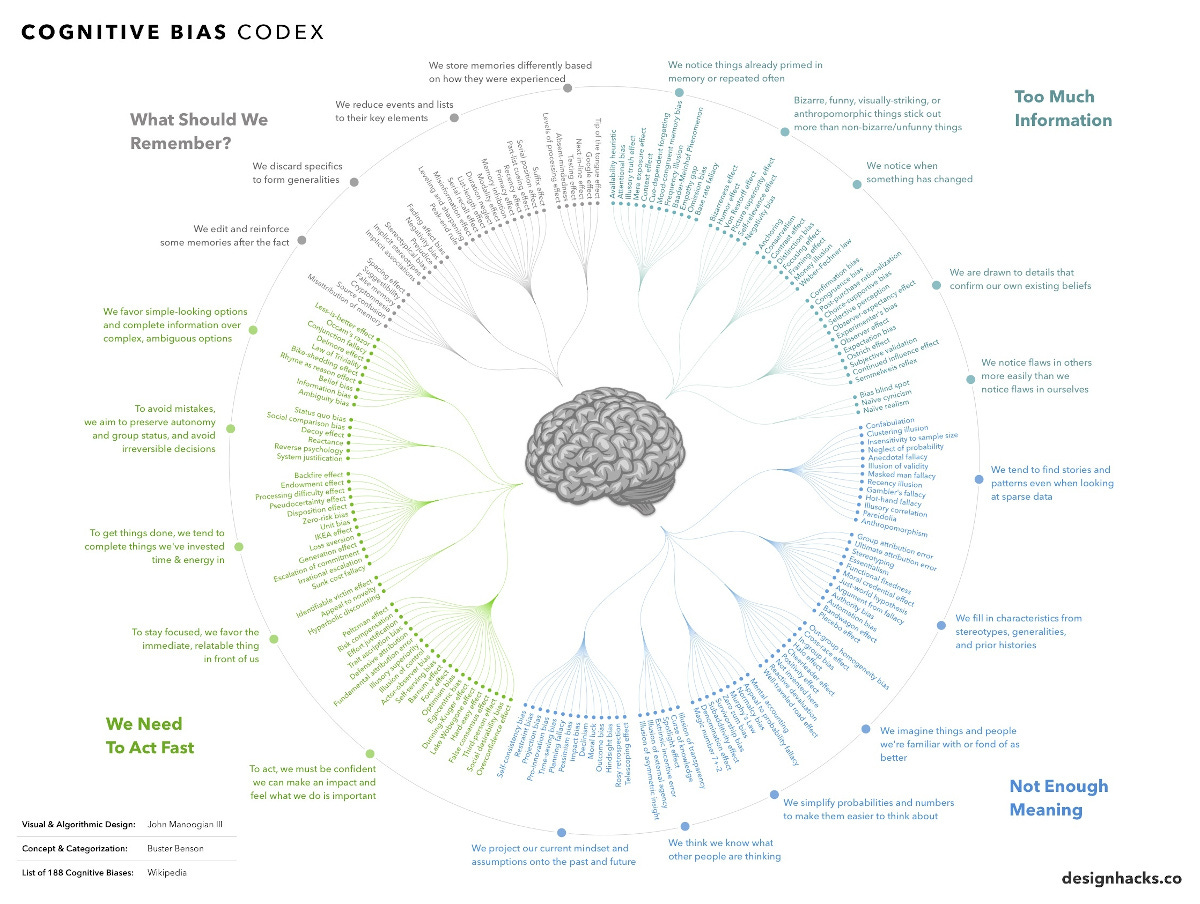

A few years ago, Jason Collins penned a blog post titled "Please, Not Another Bias," lamenting the ever-expanding collection of behavioural biases and cognitive limitations put forth by behavioural economists. I share his perspective on the discipline. A look at the endless list of “cognitive biases” established by psychologists and behavioural economists gives the impression that humans are dramatically flawed and poor at forming judgements and making decisions.

It raises a crucial question: How can we, as humans, be so ineffective at decision-making? After all, decisions carry substantial consequences and have been instrumental in shaping the survival and success of our ancestors across generations. Our inherited cognitive tools reflect the achievements of our predecessors in finding resources and mates to survive and have offspring. If we have made it this far, we cannot be entirely flawed.

Taking that perspective, this Substack will delve into the adaptive explanations for the quirks of human behaviour. Instead of pointing to seemingly surprising or strange behaviour as flaws, it will point to the good reasons behind them. By doing so, this Substack will reflect the renewed interest in adaptive explanations for human cognition as pointed out by Benabou and Tirole :

Over the last decade or so, the pendulum has started to swing again toward some form of adaptiveness, or at least implicit purposefulness, in human cognition. Benabou and Tirole - Mindful Economics (2016)

The old rationality wars

This resurgence of interest echoes the debates that unfolded two decades ago, known as the "rationality wars." At that time, Gigerenzer's school championed the idea that humans are not inherently irrational, emphasising the importance of heuristics and adaptive decision-making processes. In his terms, we exhibit ecological rationality, the ability to make good decisions in the environment we face. In contrast, Kahneman and Tversky's school focused on deviations from rationality, shedding light on cognitive biases and their significant impact on decision-making.

As often in science, rifts between scientific schools appear, in retrospect, less fundamental than they appeared at the time. Gigerenzer emphasised that—since we face computationally complex problems when having to make decisions in the world—we use cognitive shortcuts selected by evolution to help us make good decisions most of the time. On the other side, Kahneman and Tversky—who were criticising economics’ assumptions of hyperrationality—indicated that our cognitive shortcuts can result in errors in a significant range of situations. As argued by Gilovich and Griffin in a review of this debate, the rift reflected more of a difference in emphasis, with Kahneman and Tversky’s school overly focusing on biases in judgement and decision-making.

There is… one version of this critique to which researchers in the heuristics and biases tradition must plead ‘no contest’ or even ‘guilty’. This is the criticism that studies in this tradition have paid scant attention to assessing the overall ecological validity of heuristic processes… It is ironic that the heuristics and biases approach would be criticized as inconsistent with the dictates of evolution because it is an evolutionary account…. there is no deep-rooted conflict between an evolutionary perspective on human cognition and the heuristics and biases approach. Gilovich and Griffin (2002)

Twenty years after these exchanges on the rationality wars, behavioural economics has successfully transformed economics. In his 2015 presidential address to the American Economic Association, Richard Thaler stressed that behavioural economics is now part of the core of economics as a discipline. Its tools and concepts are consensual and routinely used in subfields like labour economics, development economics, political economy, etc.

What next?

In short, behavioural economists have effectively persuaded their colleagues that the former notion of humans possessing god-like computational skills was misguided. Now that it is granted, focusing on documenting yet another bias here and there is less interesting. A more compelling scientific approach is to move to a new stage in our study of human behaviour and try to make sense of the often puzzling aspects of human behaviour unveiled by behavioural economists.

Cognitive neuroscience and the comeback of optimality

This approach is certainly the future of behavioural economics, it is in a very practical sense already happening in neuroscience and economic theory. Ironically, while economists were finally listening to criticisms coming from psychology about economic rationality, in another area of psychology—cognitive neuroscience—researchers were turning their interest to economic models of rationality to suggest that the brain may work as a very efficient computational machine.

In that perspective, the brain is well-designed to quickly aggregate the evidence collected from our perception to make judgements and guide our decisions. These computations are not conscious. They are processed in the background by our networks of neurons and result in our positive or negative impressions of the different options we face when making decisions.

Developments in economic theory and the explanation of “biases”

At the same time, economic theory has made tremendous progress since the 1970s-1980s, when psychologists were finding it too simplistic. Many developments now make it possible to study human decision-making with richer and more realistic assumptions about the problems people face.

A very good example is the study of the effect of limited information on decision-making. For a long time, economists assumed, mainly for simplicity, that people are perfectly informed. This made formal models easier to solve, and it could sometime be defended as an approximation: even if people are not perfectly informed, they may be informed enough for this assumption to give good predictions about human behaviour. But this assumption is obviously very strong. For example, it means that a consumer buying a computer would have a technical understanding of all the components inside it and how they work together, as well as an understanding of the legal clauses of the lengthy terms and conditions signed at the time of purchase. It is obviously not the case.

Thankfully, the progress in information economics and game theory has improved economists’ ability to study how people make decisions when they are imperfectly informed. It leads to a new synthesis between economics and psychology. In this view, "biases" can often be seen as natural results of people not having perfect information, and the costs they face to get more. So, biases might actually be good solutions, given the informational constraints people face.

Looking into Adaptive Explanations

The arguments above are nice, but abstract. To flesh them out, I will put them to task in the next threes posts by looking at three of the most iconic biases uncovered by behavioural economics:

The hot hand fallacy,

The confirmation bias,

Our sensitivity to gains and losses relative to a reference point.

I will examine each bias and show how recent developments in economics overturn the negative view of these behavioural features as crippling limitations. If you have learned these biases from traditional behavioural economic sources, prepare yourself to be surprised.

To make sure you get the notification about the next three posts, you can click “subscribe”. The content of this Substack is free.

Very interesting Prof. Page. I am a 3rd year PhD student in Economics, interested in behavioral topics and have been struggling to deal with some of the points you write about in this post. I can't help but feel discouraged that some of behavioral economics has devolved into clever hair splitting, e.g. identifying a new bias in a new context, and that there are few policy implications that can be drawn from the research. As I start to narrow in on a dissertation topic (I am interested especially in the intersection of behavioral and environmental economics) do you have any advice as to how to avoid this trap?

I am a 4th-year Applied Psychology PhD student specializing in behavioral economics and Optimally Irrational is a book I wish existed at the start of my doctorate. My advisor is a hardcore Skinnerian and his approach to behavioral economics downplays cognitive biases while placing more emphasis on how behavior is selected by consequences in the environment. In other words, behavior is neither rational or irrational but adaptive to the context. Because of my training, I'd consider myself relatively immune from "bias bias". I have purchased the book and subscribed to the blog and I look forward to learning more from you.