Epstein files: how arguments really make people change political side

The not totally ineffective nature of political arguments

How do people, if ever, change their views through argumentation? In this piece, I present insights from a paper I will release later this year on how rational arguments work. As an illustration, I draw on the Epstein file saga and the split it triggered within the MAGA coalition.

In a famous quip, physicist Max Planck mocked the idea that even scientists, who claim to do their utmost to find the truth, actually change their minds from listening to arguments and witnessing new evidence:

A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it. — Planck (1950)

If even scientists fail to follow the evidence laid out in rational arguments, do arguments work to change minds at all? The recent split in the MAGA coalition following the debate on whether or not to release the information on Epstein’s contacts is, in that light, very interesting. It shows that, even in the messy world of politics, the emergence of new evidence can lead some to change their minds.

The weakness of rational arguments

The key to understanding how people change their minds based on evidence is to start with a correct understanding of human reason. Philosophy and our intuition can easily lead us to think of reason as a way to be good at finding the truth in order to make good decisions: being logical, being accurate, and adequately incorporating new evidence. In that view, our reason pushes us towards the truth, while it is our passions that divert us from it.

But that view is misguided. Our reasoning ability has been selected by evolution to successfully navigate our world. As members of a social species, our world primarily consists of social interactions. Most of the time, we don’t use our reasoning abilities to solve objective problems like an engineer, but to argue with others, trying to convince them as lawyers would.

As a consequence, when people engage in arguments, they are not impartial participants aiming to find an objectively good common ground; they are press secretaries for themselves and their group, putting forward the best case they can find and brushing under the rug the potential weaknesses in their side of the argument. Indeed, a study found that people regularly continue to argue, even after having realised that their initial stance was wrong!1

In politics, people typically describe their belonging to a political side as a choice motivated by the good principles behind the policies it defends. This justification actually gets the causality backwards. Political views are mostly downstream of social group memberships (e.g. kin, ethnic, professional, or religious groups). People typically do not adopt a political position as the end result of a personal reflection about what the best moral principles are. Instead, they mostly adopt the political affiliation prevalent in their family, among their peers, and their social group. It is once they have picked a side that they then look for the arguments that support their stances.

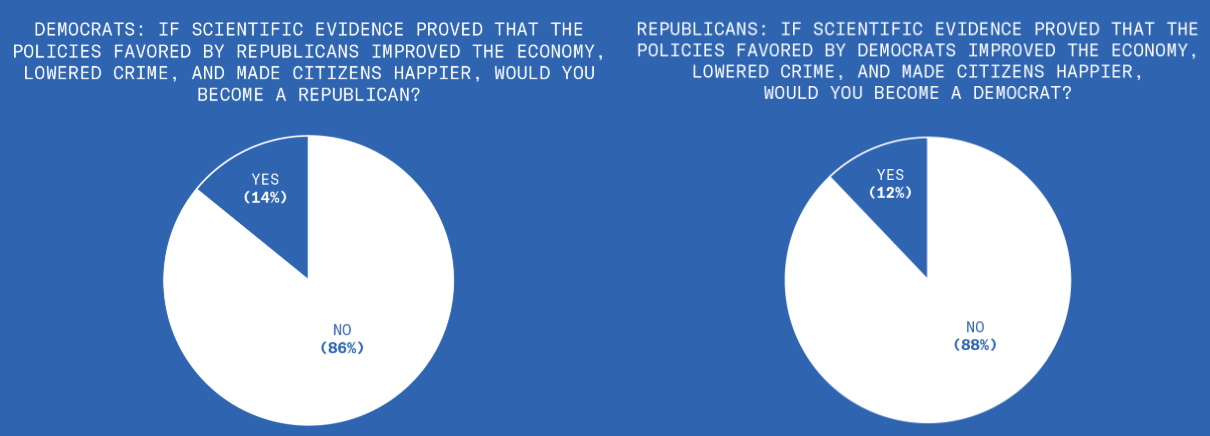

As an illustration that political affiliation is typically not downstream of impartial reasoning, David Pinsof pointed to this interesting poll suggesting, if the respondents understood the question correctly, that most Democrats and Republicans in the US would actually not want to change their political views even if it was shown by science that the positions of the other side improved the economy, lowered crime and made citizens happier.

Along these lines, studies have found that political arguments have limited effectiveness at changing people’s minds. In a highly cited study, political scientists Charles Taber and Milton Lodge (2006) found that when faced with arguments, people behave differently depending on whether it backs or criticises their view. They “counterargue the contrary arguments and uncritically accept supporting arguments.” In a recent field experiment, social scientists found that exposing people to opposite arguments on social media even made them more entrenched in their initial views.2

An ironic example of how our reasoning is tethered to our coalitional membership was given by a stunt organised by US talk show host Jimmy Kimmel. They had Trump supporters comment on statements allegedly made by Joe Biden, then they were told that the initial attribution had been mixed up and that the statement was actually from Donald Trump. The TV segment showed that, interrogated that way, several supporters switched without a blink from staunch criticism to neutral or supportive takes.3

The Epstein file saga and the MAGA coalition split

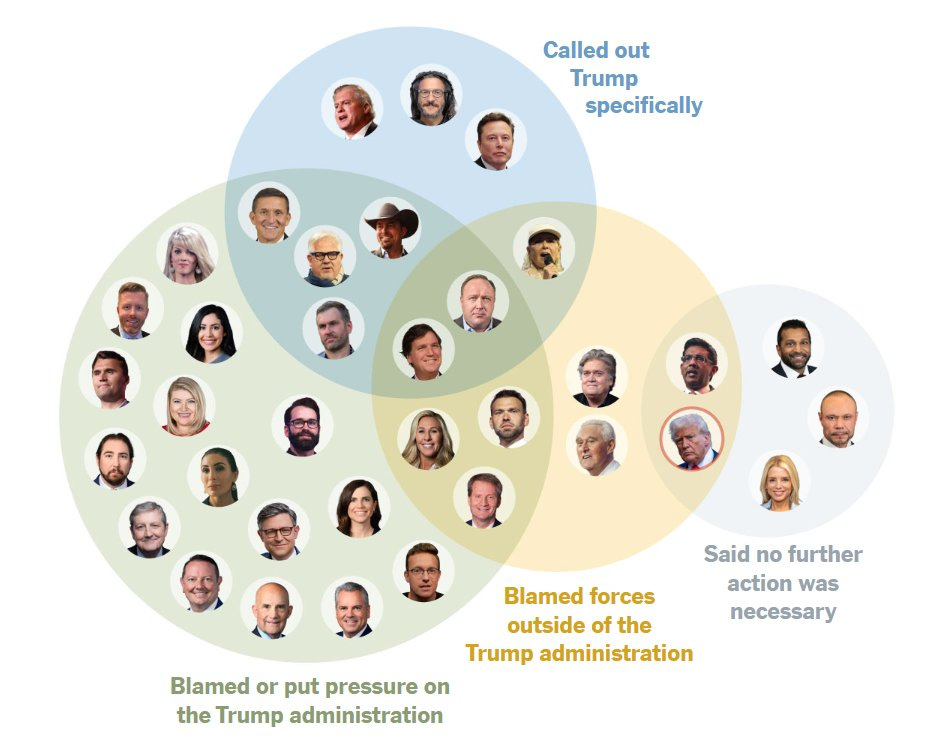

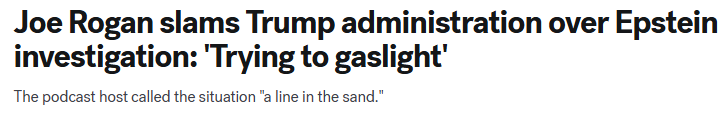

The Epstein file saga is, in that light, interesting as it showed a situation where an argument, on whether to release the information about Epstein’s connections and clients, mattered. While the supporters of Donald Trump have seemingly been willing to accept many twists and turns in the US president's stances and arguments, his decision not to release the files was noticeable for the split it created in the core of his ideological power base.

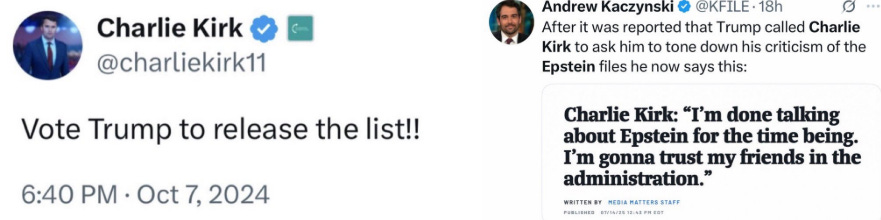

Why did that happen? The idea that arguments are very ineffective at changing political stances, given people’s coalitional bonds, could have predicted something more like Charlie Kirk’s turnaround:

If arguments were just artificial ploys to push forward one’s coalition, this is what you would expect: people realising that an argument has stopped being in favour of their coalition would just drop it and move on, like the Trump supporter interviewed by Jimmy Kimmel’s team.

However, if political arguments were nothing more than expressions of coalition loyalty, we would face a contradiction. Unless listeners are completely naïve, they would eventually realise that such arguments convey no genuine information about the world, only the preferences of the speaker. As a result, their content would become meaningless for understanding reality.

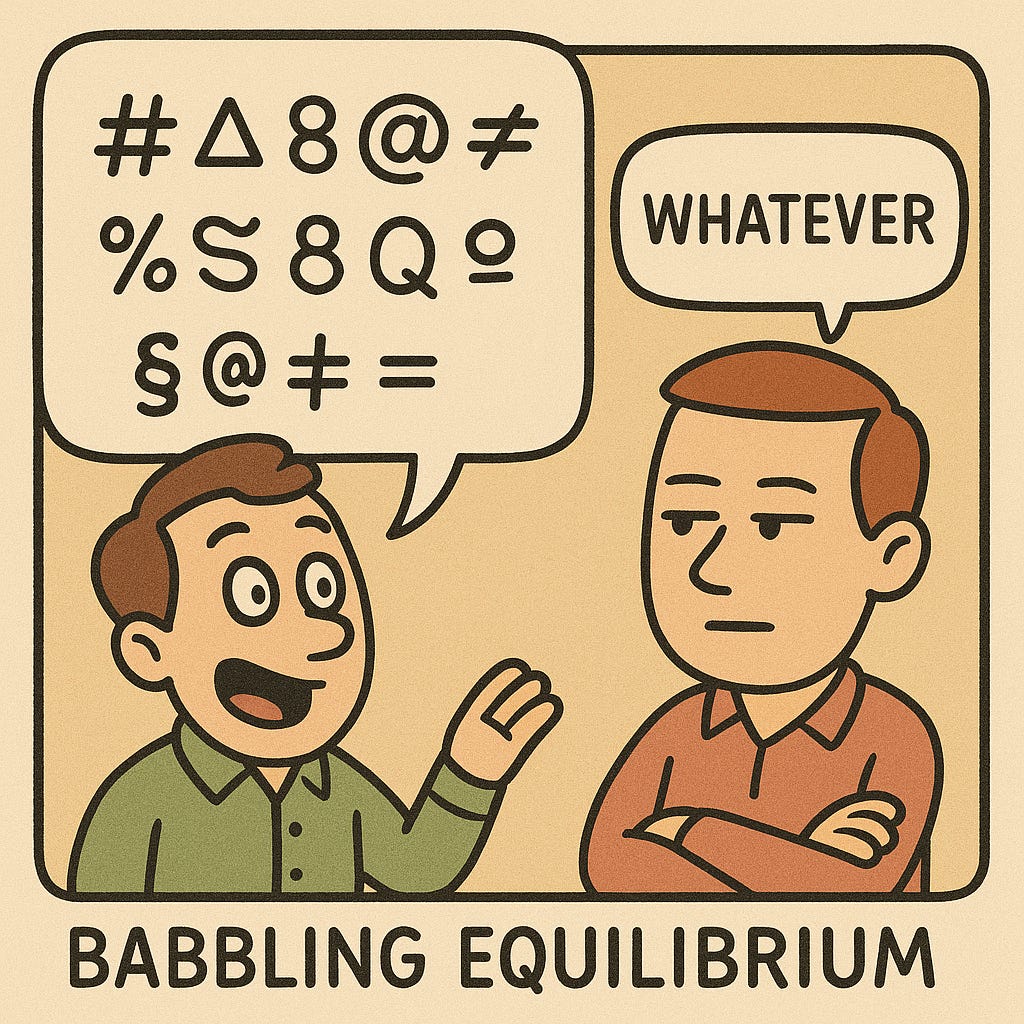

Game theory predicts that when messages carry no informational content, listeners will stop paying attention. If John claims that A is true when it suits him and denies it when it doesn't, his statements reveal nothing about A, only about his current interests. The outcome is what game theorists call a babbling equilibrium: John continues to say whatever is convenient, but others stop listening, knowing it carries no useful information.

Political arguments, therefore, must be more than that, since, in spite of their limitations, people expend a lot of effort refining them or fighting them, and they (at least sometimes) change people’s minds.4

The reason arguments are not entirely meaningless is that switching positions without an apparent justification, like Charlie Kirk did, carries a reputational cost.5 Political entrepreneurs (commentators and leaders) build their brand on proposing ideological narratives that support a coalition’s interests. While these narratives are self-serving, they have to be somewhat coherent and compatible with reality to be effective.6 The credibility of political entrepreneurs is tied to their ability to produce such compelling narratives. If they offer illogical or obviously untrue arguments, that would not convince anybody outside of their coalition, the value of what they offer drops and their reputation as valuable political entrepreneurs goes down as a result.

One of the clearest signs of providing poor ideological narratives is changing them simply because they have become inconvenient rather than because of a change in evidence. This is exactly what Kirk did, and people opposing Trump are pointing at it because it harms his credibility.

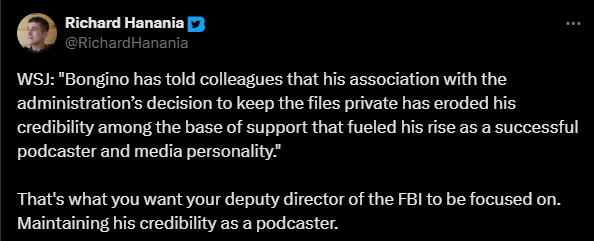

This reputational cost means that political entrepreneurs face a trade-off when an argument becomes inconvenient for their coalition: follow coalitional incentives and drop it, or follow their own reputational incentives and stick to it, at the risk of inducing tension or a split with their coalition. This trade-off was explicitly stated by Bongino (ex-podcaster, now deputy head of the FBI), as mentioned in the Wall Street Journal:

When new evidence contradicts an ideological argument used by a coalition, the way political entrepreneurs react will be heavily influenced by the source of their social status. Those who are indebted to the coalition leader(s) will be more likely to toe the line and abandon their previous argument.7 Those whose status is tied to their personal reputational capital will face greater costs to move on without a good justification. They are the ones more likely to diverge from the change in coalitional narratives and start “asking questions” and possibly eventually split off due to disagreements.

This is precisely what unfolded among pro-MAGA figures. Many had staked their personal reputations on the Epstein files, presenting them as a politically critical issue. Some, like Bongino, built personal followings through their content on social media platforms. Inconsistency carries real reputational costs, which led many MAGA commentators to hesitate, or outright refuse, to publicly abandon the issue.

Trump’s handling certainly made it even more difficult for his supporters. First, he did not leave them an exit door. His refusal to discuss the Epstein files was sudden, explicit and without enough ambiguity to provide a way for his supporters to rationalise for themselves and their audience a change in priority. Second, and even more important, he blamed his supporters who were still interested in the Epstein files and said he did not want their support anymore.

My PAST supporters have bought into this ‘bullshit,’ hook, line, and sinker. Let these weaklings continue forward and do the Democrats’ work, don’t even think about talking of our incredible and unprecedented success, because I don’t want their support anymore! - Trump statement on his Truth Social account

Given the coalitional nature of the motivation to agree or not with a political argument, such a stance is bound to make a range of supporters feel betrayed and tempted to move away from him. As a result, commentators who speak to this audience had even stronger incentives to oppose Trump’s request and to articulate and explore their concerns.8

How to help truth emerge in public debate: setting up the right reputational incentives

The discussion above highlights a key condition for public debate to be effective in uncovering truth and discarding bad ideas: contributors must be rewarded with social recognition for the quality of their arguments, not for their coalitional loyalty.

This dynamic can arise in a decentralised marketplace of ideas, where aspiring political entrepreneurs build personal audiences through the content they produce. Their social standing, measured, for example, by follower counts, emerges in a decentralised way from the match between the narratives they offer and the interests of their audience. This gives them both the freedom and the incentive to pursue their own lines of argument, rather than necessarily conforming to an official coalitional narrative.9

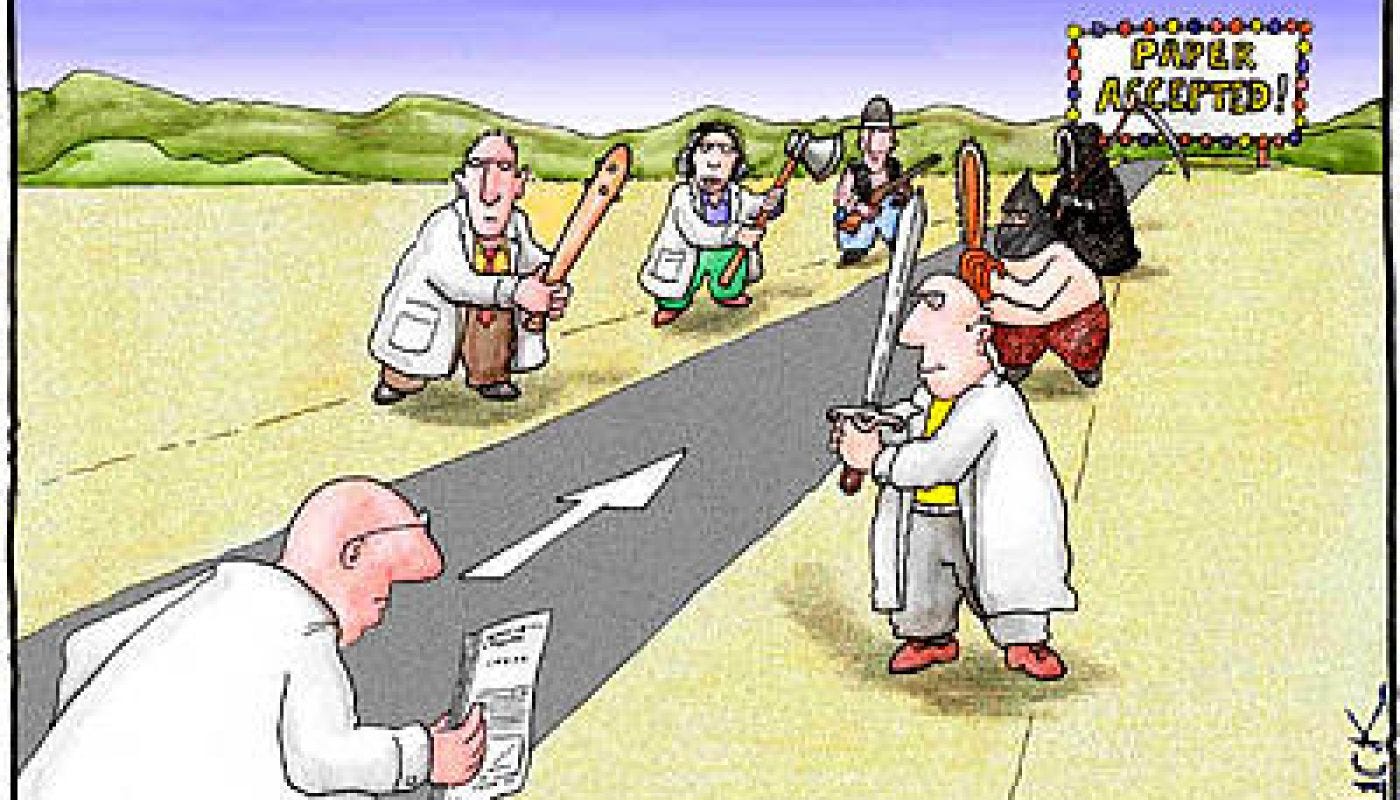

Science provides a model for such a marketplace of ideas: new ideas must to be presented in a detailed and standard way that allows close scrutiny, they are checked by peers before being published, and they are kept on record for a long time so that any silly thing you published 10 years ago might come back to haunt you today. These conditions heighten the potential reputational costs for making wrong statements.10 No wonder scientists are masters of hedging: “on the one hand, on the other hand” is the start of many of their answers to layman questions about the world. They dread bold and radical statements that come with risks of being on record as having said something wrong.

Social media platforms like Twitter, YouTube, and Substack are marketplaces of ideas with free entry for all. While they have raised a lot of concerns, they have the potential to raise the quality of public debate if contributors’ reputational concerns drive them to produce quality content.

Such an outcome is, however, not guaranteed. As he was praising freedom of speech, John Stuart Mill warned, nevertheless, that ideological conformism can still arise from a tyranny of the crowd, sanctioning anything said outside of a small Overton window allowed within a given coalition. In a polarised political environment, loyalty to one’s side and the reputational costs for failing such loyalty may trump the concerns for intellectual rigour. The public debate may decay into echo chambers where non-overlapping crowds build narratives that face less contrarian pushback. Such narratives can end up diverging radically from each other (and, incidentally, from reality as well).

For that reason, a marketplace of ideas is not enough in itself for the truth to tend to emerge; it also needs incentives shaped to sanction the reputation of political entrepreneurs who spread arguments that are found illogical or unsupported by evidence. This is a key question when designing a public sphere: how can we make participants’ incentives closer to a scientific exchange than to a shouting match between supporters of different social groups?

How to prevent the truth from inconveniencing you as a ruler

Coalition leaders who want to eliminate the inconvenient accountability generated by a marketplace of ideas have an interest in breaking reputational incentives and ensuring that all incentives are tied purely to coalitional loyalty. Here, we get an insight into a famous quote by Hannah Arendt about the role of lies and propaganda in authoritarian states: by reducing people's ability to distinguish what is true from what is not, such regimes eliminate the reputational cost of spreading falsehoods.

In 2016, Donald Trump made a notable remark about his repeated attacks on the mainstream media, one that closely echoes Arendt’s point:

You know why I do it? I do it to discredit you all and demean you all so when you write negative stories about me, no one will believe you. —Trump in 2016

By undermining the credibility of the mainstream media, Donald Trump’s modus operandi erodes the system of accountability that news media provide within the public sphere. As imperfect as it may be, this system imposes reputational costs on commentators who put forward visibly weak or dishonest arguments. In the absence of such accountability, what remains are primarily coalitional incentives, with each side promoting whatever narrative serves its interests, with little regard for rigour or accuracy.

How do people change their minds in response to rational arguments? The idealist view holds that people simply follow the force of reason: good arguments prevail because they are right. In contrast, the cynical view claims that arguments never truly change minds, they are merely fig leaves for underlying interests, easily replaced when no longer useful.

The perspective I propose lies somewhere in between. Arguments can shift people’s views, even when they are primarily motivated by personal or group interests. This is because the communication games we engage in create reputational incentives: they punish bad faith and reward those who acknowledge strong arguments.

But for arguments and debate to effectively filter out bad ideas and elevate better ones, reputational incentives must be strong enough to outweigh personal and coalitional loyalties. Only in contexts where this condition is met, like in science, are arguments likely to change minds on the basis of their merits.

References

Arendt, H. (1951). The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

Bail, C.A., Argyle, L.P., Brown, T.W., Bumpus, J.P., Chen, H., Hunzaker, M.F., Lee, J., Mann, M., Merhout, F. and Volfovsky, A. (2018). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(37), pp.9216–9221.

Fetterman, A.K., Curtis, S., Carre, J. and Sassenberg, K. (2019). On the willingness to admit wrongness: Validation of a new measure and an exploration of its correlates. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, pp.193–202.

Mercier, H. (2020). Not Born Yesterday: The Science of Who We Trust and What We Believe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Planck, M. (1950). Scientific Autobiography and Other Papers. London: Williams and Norgate.

Taber, C.S. and Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), pp.755–769.

Fetterman et al. (2019).

Bail et al. (2018).

Such segments obviously can select a few interviews among many and should not necessarily be seen as representative.

Mercier (2020)

For a full treatment of this question, see my posts on what reputation is and my post on what communication games are and what role reputation plays in them.

I discussed this in these two posts: Why and how political ideas matter, and What are the chances you are right about everything?

Indeed, adopting obviously wrong and preposterous ideological narratives in favour of the coalition and its leader is a signal of loyalty and of how the individual incentives are purely to stick to their existing coalition. [ref]

Because making up one’s mind in politics is primarily about choosing a coalition the Wall Street Journal’s publication of an alleged letter from Trump to Epstein actually prompted some of his supporters to rally to his defence. Whatever the content of the argument, criticism from outside a coalition can help mend internal tensions.

Though they risk falling to audience capture.

Compare how the careers of star scientists were wrecked by evidence of fraud with those of politicians, who are often (re)elected even after being convicted in a court of law.

Some qualifications on this

1. Since Trump always lies, it's reasonable to reject even a superficially reasonable statement when you learn that Trump said it. And conversely, you need strong reasons to reject a statement from someone you know to be truthful.

2. The usual bogus symmetry. Republicans believe loads of false things, non-Republicans far less. So, any explanation that doesn't predict this must be wrong.

3. Weight of evidence. It's not rational to abandon a belief based on extensive evidence because of a single piece of contrary evidence, especially one presented to you by a psychological experimenter (a group notorious for trickery and deception).