What are the chances you’re right about everything?

The somewhat (but not entirely) arbitrary nature of political ideological bundles

Politics is not just about abstract and intellectual disagreement on principles to organise society. It takes the form of a conflict between different sides. Whatever side we are on, we tend to believe that it is right and that the other side is wrong. Being right seems easy to us, you just have to be clear-minded. Those on the other side who are wrong must therefore be either stupid, intellectually dishonest, or both.

But what are the chances that your political side is right on everything? One possibility is that each political side articulates positions based on principles. Perhaps your side is the one with the right/just principles, while the other one isn’t.

The somewhat arbitrary nature of ideological bundles

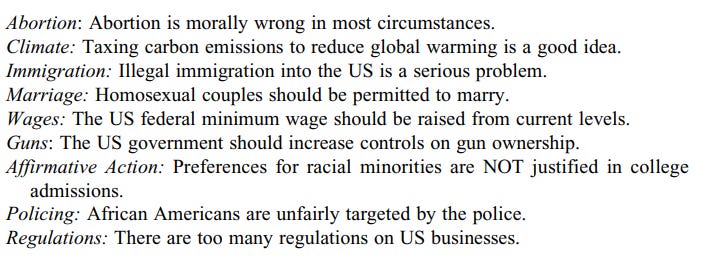

Looking at political positions, it is hard to identify simple principles at the root of the political bundles supported by a political side. In a 2020 article, “What are the chances you’re right about everything?”,1 philosopher Hrishikesh Joshi pointed out the uncanny correlation found in the answers to these political questions, in spite of their diverse nature:

These issues are about very different questions in diverse domains of social life. The positions one might have on these issues seem hard to relate to a few coherent principles. For that reason, it makes sense to think of the political space as multidimensional: many issues, not just the traditional opposition between more or less economic redistribution, form possible lines of opposition. Nonetheless, a survey in the US found that an answer to one of the questions above predicts pretty well the answers to other questions.2

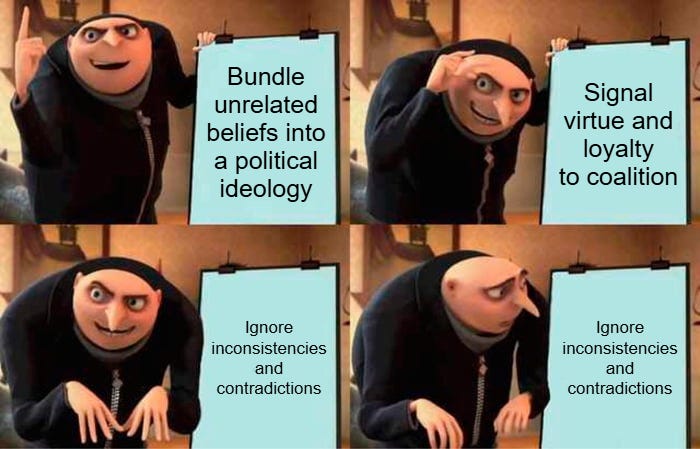

In other words, political ideologies come in bundles. Are you on the left? Then you are likely to be for more redistribution, women’s rights, the tackling of climate change, the fight against discrimination towards minorities, etc. Are you on the right? Then you are more likely to be for a small government, to oppose the erosion of traditional values, and to be critical of immigration.

The fact that these positions on different issues are bundled that way typically comes to us as natural. For those who care about politics, their side is the good side fighting, at best, misguided, at worst, nefarious political opposition. Being on the good side means being right on all these different topics.

How coalitional realities shape ideological bundles

But this vision is a chimera. Political ideologies are not perfect conceptual frameworks designed primarily for their logical consistency. They articulate the interests of political coalitions. This view was recently developed in a great paper by David Pinsof and co-authors: Strange bedfellows: the Alliance Theory of Political Belief Systems:

[…] political belief systems are not so much “philosophies” as collections of ad hoc justifications, rationalizations, moralizations, embellishments, and rhetorical tactics designed to advance the interests of complex political alliances in competition with their rivals. Moral principles are not so principled. Core values are not so core. Ideological worldviews are not designed to literally view the world but to serve strategic functions like signaling allegiance or mobilizing support. — Pinsof et al. (2023)

Furthermore, they point out the flexibility of coalition formation. The structure of political coalitions in a given country is historically contingent and somewhat arbitrary.

Small variations in initial social conditions can feed on one and another snowball into seemingly arbitrary alliance structures — Pinsof et al. (2023)

It explains why, across countries, parties on the same political side have often landed on different positions. An example is the attitude of left-wing parties towards nuclear energy: while many Green and left-leaning parties in Western Europe have long opposed nuclear power on environmental or safety grounds, the French left has traditionally supported it as a low-carbon energy source aligned with national industrial policy.

It also explains why, across time, parties can move to very different political positions. A very good example is the transformation of the US Southern Democrats over the 20th century. For much of the early to mid-1900s, Southern Democrats combined economic progressivism (support for labour rights, public investment, and elements of the New Deal) with social conservatism and segregationist positions. This ideological configuration reflected the coalition that sustained the Southern Democrats: an alliance of local elites and economically disadvantaged white voters. As national Democratic politics gradually aligned with civil rights and racial equality, the coalition fractured, and many conservative white voters shifted to the Republican Party in the South.3

As a consequence of the historically contingent formation of political sides’ positions they often bundle seemingly contradictory stances. The US right, for instance, contains support for pro-life positions (against abortion to protect the life of unborn fetuses) and pro-gun positions (against gun regulation that would limit mass shootings in schools, killing children). On the US left, there are calls to “believe the science” on topics like climate change or policies during pandemics against right-wing “deniers,” in parallel to descriptions of science as “Western” and merely “one way of knowing”.4

This view explains another aspect of coalitional politics: on any new issue, coalition members often do not have strong preferences initially, but wish to make sure they have the “right” position from their coalition. As a consequence, when a radically novel situation arises, there is often a time of uncertainty where it is not clear to coalition members what position the coalition should adopt. People look at each other, waiting to see where the positions will progressively align. A few key coalition leaders might show the way and lead an informational cascade that lands the coalition members collectively supporting one position or the other.

Ideologies are more than vacuous justifications

The alliance theory of political ideology rightly pushes back against a naïve view of political ideology. However, it faces a natural question: if ideologies are simply ad hoc justifications, why do people care about them? If political conflicts are, in the end, only raw conflicts of interest, why do people talk to each other, try to find reasons to justify their positions and sometimes spend a lot of time trying to convince people on the opposite side? In other words, what’s the point of ideologies? If it were common knowledge that they are just fig leaves on naked interests, why would people pay attention to them?

The perspective on political ideologies I have developed shares the observation that political ideologies are somewhat arbitrary while also explaining why people care about them: they play a role in the bargaining between social groups for the allocation of rights and resources in society.

Any group of people, large or small, working together needs a kind of understanding of how the costs and benefits of social cooperation will be split: who does what, and who gets what. When groups are as large as a society, such understandings are labelled “social contracts”, not in the sense of actual contracts agreed to by ancestors, but as de facto agreements that people are willing to follow. — Why and how political ideas matter

For these social contracts to work, their content cannot be entirely arbitrary:

ideologies are not just a bunch of fake principles simply putting a mask on the raw interests of social groups. […] For an ideology to work, it needs to have a binding force, making its respect somewhat credible. The principles of an ideology will point to specific solutions in specific situations. People adhering to an ideology know they can use the principles of that ideology to adjudicate their practical disagreements. — Why and how political ideas matter

To adjudicate how to organise society practically, a political ideology’s internal principles need to be consistent, and its factual assumptions must be compatible with reality. Otherwise, they are bound to lead to contradictory or unachievable practical solutions.

How ideologies get formed and evolve

The function of ideologies as legitimation of a coalition’s preferred position and the requirement to be conceptually consistent and factually right is the source of tension.

At the frontline of ideologies, political entrepreneurs face new problems that need adjudication: should we support A or B? Sometimes, the principles of the ideology or the jurisprudence of past decisions offer clear solutions. Other times, they do not, and new decisions have to be made on the spot. The main challenge political entrepreneurs face is pragmatic: to propose new positions that can be acceptable both to existing members and to potential newcomers, thereby increasing the size of the coalition.

Given how ideologies are made up in such a historically contingent way, they are riddled with contradictions, small and large. The different policy positions supported by a coalition might conflict with each other, or they might conflict with the proclaimed principles supported by the coalition. They might also rely on dubious factual claims that are accepted too readily by coalition members because they are convenient for the coalition’s positions.

These ideological contradictions are commonly papered over with motivated reasoning, making us downplay or ignore the cracks in our political positions. These contradictions are, however, not free of cost. In the public arena, political entrepreneurs compete to sway undecided people to join their coalition. Ideologies that are based on consistent normative principles and credible factual beliefs are more likely to be convincing and effective at attracting supporters. The ideological inconsistencies of a coalition are tracked by their opposition and brandished publicly as proof of hypocrisy or foolishness to undermine their credibility.

Within coalitions, expert ideologues track such inconsistencies. One seemingly reasonable solution could be to start by identifying fundamentally good and coherent principles and deduce from them all practical positions. This was explicitly the process proposed by Kant in building a moral philosophy.

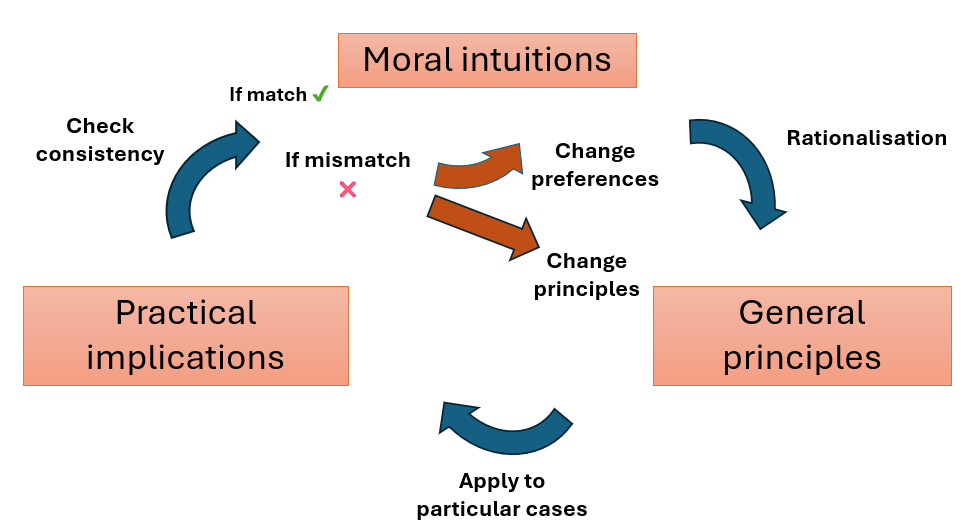

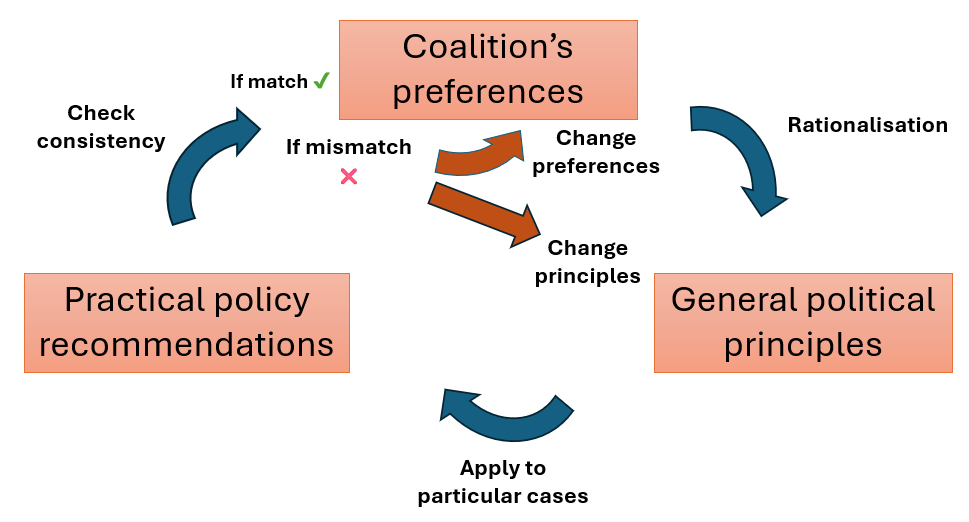

The political philosopher John Rawls famously criticised the idea of proceeding that way.5 He did not see general principles as a starting point, but as a way to make our positions consistent. If our current moral principles conflict with our intuitions, we might either change our intuitions for them to be compatible with our principles or change our principles, for them to reflect our intuitions. He described the consistency we can eventually reach from this back and forth between changing principles and changing intuitions as a “reflective equilibrium”.

I think that the idea of reflective equilibrium can usefully be applied to explain how ideologies progressively evolve. Similarly to what Rawls describes, political coalitions can go back and forth between changing their ideological foundations and changing their practical positions. Changing practical positions has costs and benefits: a coalition might lose some support from some groups by doing so and gain some support from others. Changing ideological foundations can have even more radical costs and benefits as it may lead to a range of practical policy positions different from the ones currently supported by the coalition (some of which might be clear now and some of which might only become clear later). Changes in ideological foundations can generate uncertainty about the future of the coalitional social contract.6

If an ideological innovation helps a coalition to justify its current positions and explain away tensions and apparent contradictions, it might be adopted easily. It then comes at little cost and brings great benefits. If, on the contrary, it requires revising a wide range of practical positions to make them consistent with these new principles, it is very costly to adopt. For that reason, fundamental ideological revisions are typically undertaken in times of crisis, when a coalition is failing and sees radical change as a last resort.

For any coalition aiming for power, there is a trade-off between pragmatism (making ideological compromises to build a winning coalition) and ideological consistency (only accepting new positions that are compatible with previous principles). Since survival in politics requires successfully forming a large coalition, pragmatism often wins. That is why coalitions’ ideologies are typically inconsistent and determined by a historically contingent aggregation of social groups. On any political issue, there might be a conflict between some of the coalition’s professed principles and its preferred practical position.

The pressure for consistency and accuracy is nonetheless always present,7 and political intellectuals spend time and effort codifying ideologies. They are political entrepreneurs working to make ideologies both more consistent and better able to provide suitable justifications for practical political positions desired by a coalition.8

We are unlikely to be “right” on everything

Reflecting on the uncanny correlation of attitudes on many diverse political issues, Joshi draws some conclusions about what this tells us about our own political views: we are unlikely to be “right” on everything.

The fact that doxastic attitudes toward orthogonal propositions cluster together among the population raises an epistemological problem. Suppose a person finds herself having the beliefs that are typical of one of the clusters of political opinion. Such a person, I shall argue, should moderate her political beliefs. For, the orthogonality of the issues involved makes it highly likely that something is going awry epistemically – either her beliefs have been subject to problematic irrelevant influences or she is in possession only of a biased subset of relevant evidence. — Joshi (2020)

A key question here is: what is being right? Joshi adopts the view that there are true moral principles. In that sense, you can be right or wrong about your political views. Without taking such an epistemic stance, we can still say that we are unlikely to be right about everything in the sense that a close examination of our practical political views and our professed political principles is unlikely to reveal perfect consistency. In other words, it is unlikely we have reached a reflective equilibrium. Achieving this is difficult. It requires either abandoning some cherished positions in order to be consistent with principles, or finding new general principles that rationalise our diverse positions. Unfortunately, our coalitional bonds tend to prevent us from achieving such a goal, as it would often require disagreeing with the positions of the people on our side.

For most of us mortals, who are not political philosophers like John Rawls, our views are likely riddled with inconsistencies that we are either unaware of or unwilling to openly admit. Political opponents’ criticisms create pressure to eliminate such inconsistencies. This pressure is, however, imperfect, and it is balanced by the benefits of pragmatic ideological compromises that help sustain large coalitions. To the extent that contradictions are small, political ideologies can accommodate them.9 We are therefore unlikely to be “right” on everything, and this fact should encourage humility in us when considering our political positions compared to others.

References

Carmines, E.G. & Stimson, J.A. (1989). Issue Evolution: Race and the Transformation of American Politics. Princeton University Press.

Cullen, S. (2018). Partisans align across unrelated ethical topics. Retrieved from https://osf.io/38axf

Joshi, H. (2020). What are the chances you’re right about everything? An epistemic challenge for modern partisanship. Politics, Philosophy & Economics, 19(1), 36–61.

Pinsof, D., Sears, D.O. & Haselton, M.G. (2023). Strange bedfellows: The alliance theory of political belief systems. Psychological Inquiry, 34(3), 139–160.

Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Justice. Harvard University Press.

Dan Williams included this article in his syllabus on politics, truth and ideology.

The list of political positions was designed by philosopher Simon Cullen (2018), who also conducted a survey finding the correlation between answers among US respondents.

This transformation is a textbook case of what political scientists call a “realignment”: a deep, lasting shift in party coalitions, often triggered by changes in the social makeup of coalitions and the issues that define them (see Carmines and Stimson 1989).

Maarten Boudry has a related post on the paradoxical evolution of parts of the left against the rationalist Enlightenment values that characterised it in the past.

He developed this argument in his book A Theory of Justice (1971).

In fact, once we follow this angle, it justifies the use of the procedure suggested by Rawls to agree on normative principles. We should aim for a reflective equilibrium, not because consistency is a higher good (after all, why would it be?), but because agreeing on normative principles is looking for rules we would want to be applied to social situations. Consistency is required for these rules to work in practice. Like proper contracts, a social contract needs clear principles to cater for all situations and avoid loopholes, but also to ensure that these principles lead to clear and unique solutions in each situation.

Because we aim for such an agreement on consistent principles, the principles are not coming first. They need to reflect our preferences. However, since our preferences might contain contradictions, we may need to adjust our proposed principles or compromise on some of our preferences. This gives a realist justification to a process that Rawls presented primarily as a desirable endeavour to form a moral system.

Consistent ideologies relying on accurate facts provide more reliable social contracts. Inconsistencies may generate conflicting recommendations in specific situations and therefore fail to provide a solution commonly agreed upon in the coalition, and factual inaccuracies are bound to lead to wrong solutions. Political adversaries look for inconsistencies and inaccuracies in a coalition’s ideological positions to point them out and peel off some of its members by promising an alternative more consistent with their practical views.

This epistemic pressure is imperfect: political debates are not scientific debates, the degree of fact and logic checking is looser, and the potential reputational costs for failing to respect principles are lower.

Karl Popper described science as an evolutionary process where the best ideas eventually win. It is telling that this process is imperfect even in science. Many bad ideas can persist for a long time, in spite of the institutional aspects that are geared towards preventing this: the vetting of new ideas by peers, the requirement for statements to be as clear as possible, the use of commonly agreed techniques and argument, and the long record of ideas previously put forward that can be revisited at any time. Politics is far from this ideal and, given the obvious limitations of science, those in the formation of ideas in politics will only be much larger.

These aspects of political debates weaken the ecological pressure to weed out logical inconsistencies and factual inaccuracies. That is why we can expect a lot of incoherence to persist over time in political ideologies.

Political ideologies work, in that sense, very much like scientific paradigms (sets of methodological principles and accepted facts that guide scientific inquiry) that can accommodate some anomalies and contradictions, as long as, in practice, they work well to guide the actions of scientists.

Great post, Lionel, and thanks for referencing my work. I largely agree with you here. In the Alliance Theory paper, we write that, "allies must support one another in conflicts—for instance, by defending their allies’ reputations, attacking their rivals’ reputations, and mobilizing support from third parties." Naturally, reputational attacks and defenses will be more effective if they are (or appear to be) factually correct. Likewise, third parties will be more effectively mobilized by (the appearance of) truth and consistency than by blatant deception and hypocrisy. We write in our response to commentaries that partisans often "try as hard as they can to rationalize [their inconsistent beliefs]--that is, to make them seem perfectly reasonable and not at all odd. They might even succeed." We also write that "Political discourse is a competition to satisfy people’s moral intuitions, to rally them to our side, and to draw them away from the other side. We must all recognize and feel these moral intuitions; otherwise, we could not use them to rally supporters."

So the propagandistic biases we discuss are constrained by (the appearance of) reality and morality. The constraints are pretty loose, as reality and morality can be mimicked by sophistry and moralism--mimicry that political zealots will be eager to accept and promulgate. Third parties might even have some motivation to accept the mimicry--they might possess a certain level of ideological gullibility--insofar as this gullibility helps them join up with powerful alliances. Even those within the coalition may benefit from the propagandistic narrative if it enhances commitment and support for the group. The cost of any deception may be outweighed by increased success in collective action and intergroup competition.

You pose the question: "If it were common knowledge that [ideologies] are just fig leaves on naked interests, why would people pay attention to them?" The answer is, of course, that they wouldn't. This implies that if ideologies *were* just fig leaves on naked interests, partisans would have a *very strong political incentive* to hide that fact and prevent it from becoming common knowledge. They would construct elaborate excuses and rationalizations designed to make their naked interests seem high-minded, beneficent, and truthful. They would shun and condemn anyone who rejected such excuses and rationalizations, because they would be a threat to their coalition. If they failed in preventing the ugly truth from becoming common knowledge, their coalition would lose power. A lot of political discourse is about calling out the other side's ugly truths and covering up our own side's ugly truths.

So if ideologies *were* just fig leaves on naked interests, they would almost certainly lack the *appearance* of being fig leaves on naked interests. While I think ideologies serve several functions beyond covering up ugly truths about naked interests, I think covering up such ugly truths *is* one of their functions, along with bolstering commitment to the group, signaling group loyalty, competing for ingroup status, and winning over third parties.

If there is any disagreement here (and I'm not sure there is), it may relate to moral asymmetries between political coalitions. It seems like you're suggesting that each side has different moral principles they're fighting to implement? If so, I disagree. I think partisans share the same basic moral psychology: our shared moral intuitions are the "high ground" that we compete to capture. As we write in the paper: "Rather than disagreeing about justice in the abstract, partisans may merely disagree about who deserves status (and how much), who deserves condemnation (and how much), and who deserves sympathy (and how much). Indeed, much of political discourse plays out against a backdrop of tacit moral agreement. Disputants compete to frame their opponents as immoral—e.g., unfair, selfish, disrespectful—while relying on shared assumptions of what counts as moral."

Plus, I don't think partisans know much, or care much, about how practically effective their policies are in upholding their apparent moral principles. What they mainly care about is their group gaining power, status, and resources in competition with rival groups, and themselves gaining power, status, and resources in competition with their fellow group members. It's a cynical view, I know, but I think it's essentially correct. For instance, there is some polling data indicating that most partisans would refuse to switch parties even if scientific evidence proved that their party's policies failed to promote the common good: https://thepulseofthenation.com/#the-common-good

Of course, this cynical view is something that both sides will have an incentive to cover up and deny, in favor of their more uplifting and group-mobilizing narrative. And they will busily search for theories of ideology that vindicate the moral superiority of their side--or at least, theories that try to soften the reputational damage that the truth might inflict. That some theories of ideology are more emotionally threatening than others is, in my view, one of the many empirical facts that any good theory of ideology should be able to explain. I think Alliance Theory (along with my work on social paradoxes) can explain it. https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/avh9t_v1

I agree with much of this analysis, but I think that it neglects deeper causes of ideologies. I believe that ideologies are not so much justifications of ad hoc political coalitions (as you argue) as rationalizations of non-rational psychological perceptions of the world.

Voters choose between ideologies based on their underlying psychological temperament (i.e. they use the non-rational part of their brain).

That temperament is largely determined by genetics, but parenting, culture, and life experiences also play a role. This explains why 30-60% of the variance in ideological views can explained by by genes.

For those who are interested, I go into more detail here:

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/where-does-ideology-come-from