Why Reason Fails

Reason, touted as what makes us distinctively human, is not the tool we think it is

The achievements of human reason are impressive. In recent years, scientists have delved into the microscopic aspects of reality, finding proof of the existence of the Higgs Boson by smashing tiny particles at 99.99% of the speed of light in the Hadron Collider. At the other end of the scale of the universe, they have measured gravitational waves generated by the collision of black holes 1.3 billion light-years away.

Thus, it appears paradoxical, or in layman's terms, baffling, to observe that these achievements coexist with widely held unreasonable beliefs. Today, large proportions of the world population do not believe in well-supported scientific concepts like the theory of the Big Bang, biological evolution, or the efficacy of vaccines. To understand why this is so, we need to reevaluate our understanding of what reason is and why it exists.

The selection of reason

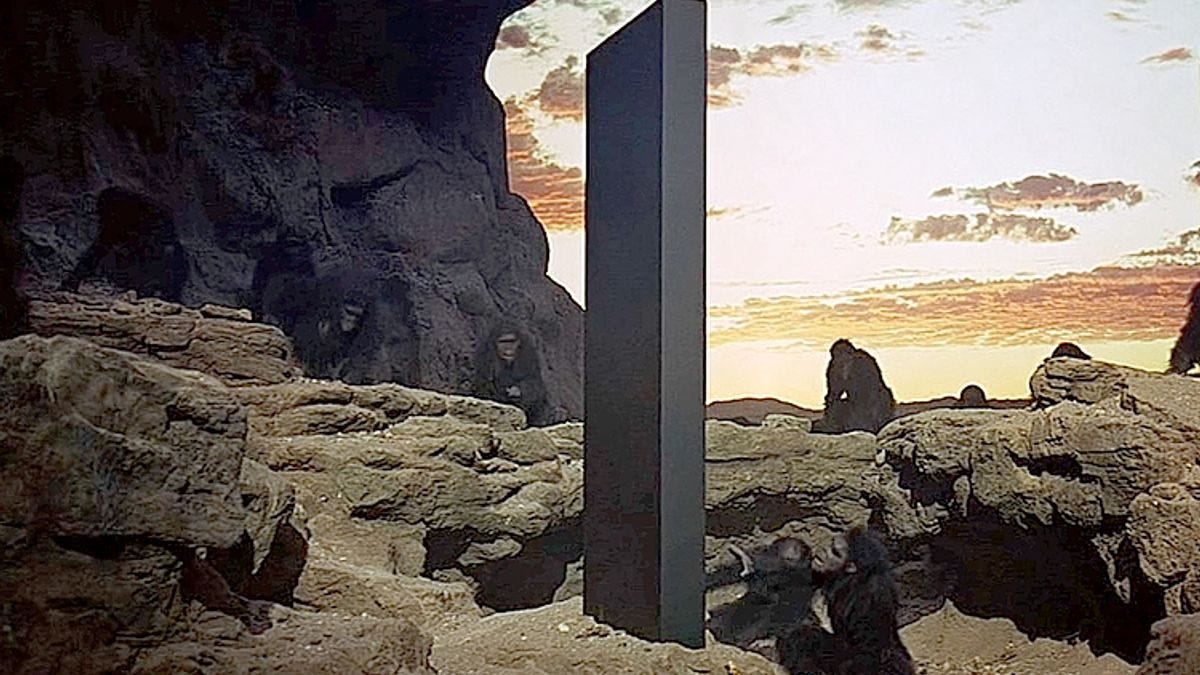

One of the most iconic scenes in 20th-century cinema is the opening of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), where a group of apes encounters a black monolith and suddenly learns to use tools. The monolith serves as a symbol of the evolutionary leap wherein humans acquired the superior cognitive abilities that set them apart in the animal kingdom. The scene concludes with a transition from a bone tool to a space station, emphasizing the role of these cognitive abilities in the scientific accomplishments of humanity.

Reason, the power to think, understand, and form judgements logically is seen as typically human. It has led to incredible progress in knowledge in sciences that have allowed the human race to achieve control and mastery over the earth and its local surroundings.

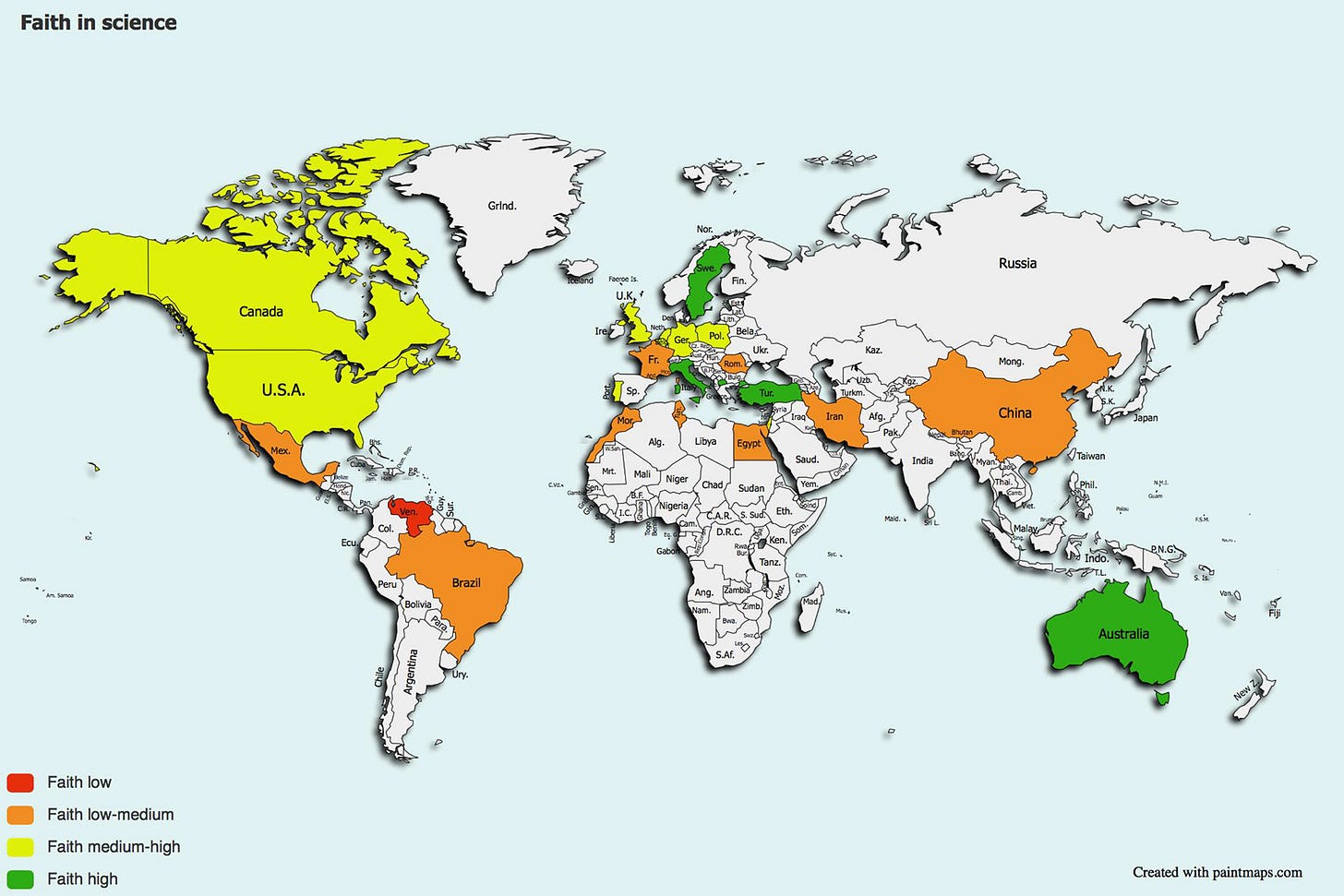

However, this notion of humans as beings primarily characterised by access to reason is somewhat at odds with several realities. Beliefs that starkly conflict with the best available evidence are common. Even in affluent countries, teeming with technologies born from scientific understanding, faith in science is not invariably strong.

This discrepancy stems from a misconception. We are inclined to believe that reason emerged as a way to find what is right, to find the truth. From this perspective, there appears to be a direct link from discovering tool use to ultimately unravelling the laws of the universe and venturing into space. Yet, in actuality, reason likely did not evolve to help us be right, but to convince others that we are.

The argumentative function of reason

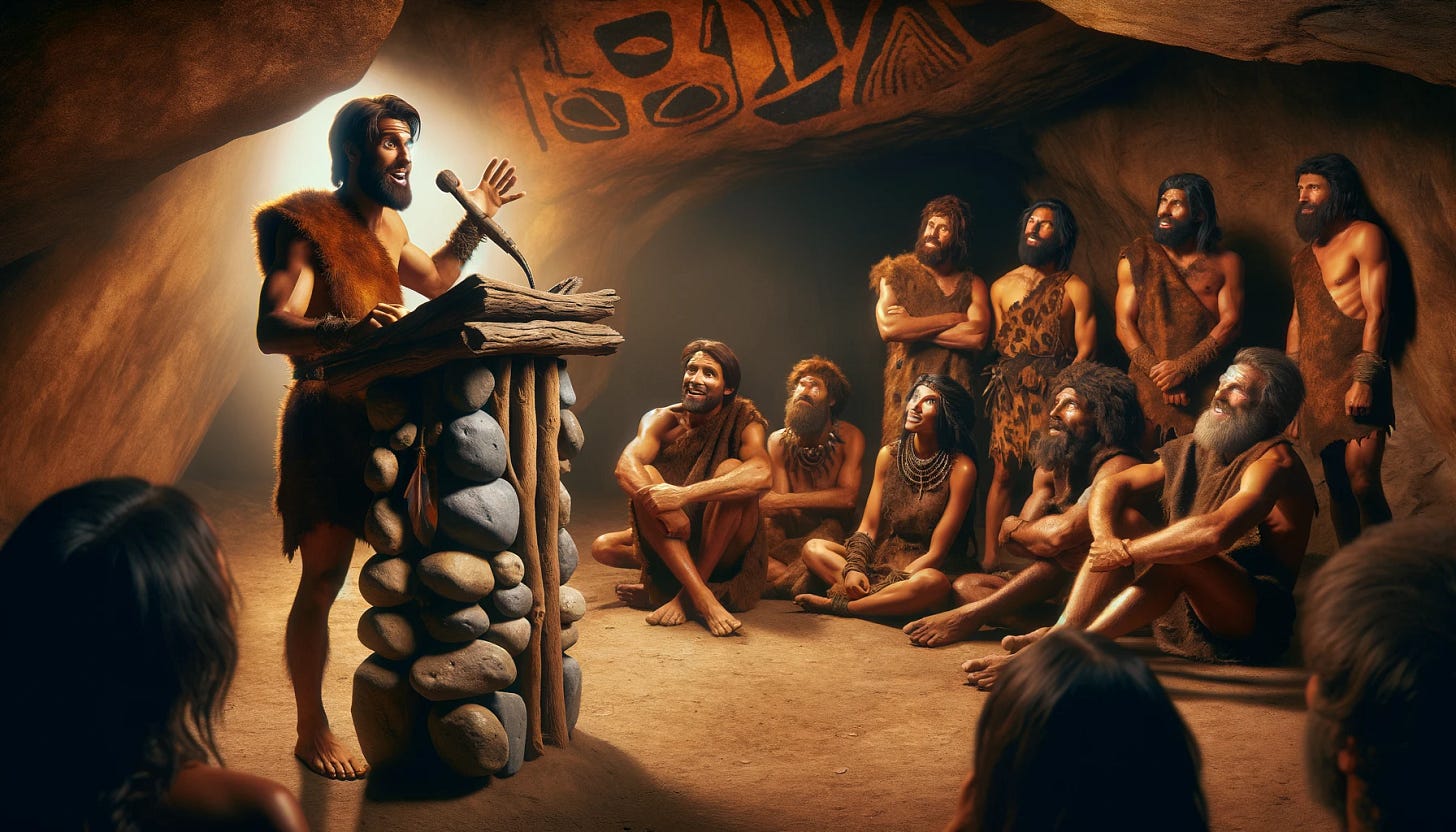

The psychologists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber have put forward the idea that the argumentative function of reason has been the main driver of its evolutionary selection. In their influential article “Why do humans reason?”, they explain:

Reasoning is generally seen as a means to improve knowledge and make better decisions. However, much evidence shows that reasoning often leads to epistemic distortions and poor decisions. This suggests that the function of reasoning should be rethought. Our hypothesis is that the function of reasoning is argumentative. It is to devise and evaluate arguments intended to persuade. - Mercier and Sperber (2011)

In short, our ancestors were not selected for their ability to understand the laws of Nature behind the motion of planets, but to convince others to cooperate with them, to trust them, and to be trustworthy themselves. This persuasive skill was crucial for our predecessors' success. Conversely, the ability to critically evaluate others' persuasions—spotting inconsistencies or flawed evidence—is also a vital skill that Mercier and Sperber term epistemic vigilance.

Our reasoning ability likely emerged as a by-product from an arms race between the ability to present compelling arguments to others, and the ability to scrutinise others’ arguments. The view emerging from Mercier and Sperber’s theory is that we have not been selected to think as scientists but to think as lawyers. Scientists may be more rigorous, but lawyers are those best at convincing others. The ability to reason logically and rigorously, in that perspective, was not selected because it helps us to have the right beliefs, but because it helps us navigate the games of social communication where convincing others and not being taken for a ride are key to being successful. In that perspective, the mere ability to reason rigorously is not necessarily associated with social success. In many situations, people with more accurate beliefs are superseded in social interactions by people who have less knowledge but navigate social interactions more successfully.

This perspective explains many of the travails of how we “reason” in real-world situations. In adversarial debates, the objective for lawyers isn't necessarily to pursue truth diligently; selective evidence presentation, overlooking inconvenient truths, and employing suggestive language are tactics that muddy our discussions and obscure the path to a shared understanding based on a reasonable interpretation of the evidence.

Even when cornered at the losing end of a debate, people seem to often—consciously or subconsciously—reject the logical implications of the discussion and refuse to admit that they were wrong. In a study involving 120 participants over two weeks, people reported 72 instances where they thought they were wrong about something but did not admit it to their interlocutor (Fetterman et al., 2019). Instead of conceding, we may keep maintaining the façade that we believe in our arguments.

Rigorous arguments are not entirely ineffective at changing our minds, but they are not as effective as we ideally think they should be when we usually picture reason, as guiding how we form and change our beliefs. Instead, we have vested interests in our personal beliefs and the beliefs of our social groups. And these interests can make us very resilient to reasonable counter-arguments.

Education an unlikely solution

Education is often seen as the solution to improve public debate, allowing enlightened citizens to converge on common positions. This view is, for instance, developed by Gutmann and Thompson in their book Democracy and Disagreement (2009).

To prepare their students for citizenship, schools must go beyond teaching literacy and numeracy, though both are of course prerequisites for deliberating about public problems. Schools should aim to develop their students' capacities to understand different perspectives, communicate their understandings to other people, and engage in the give-and-take of moral argument with a view to making mutually acceptable decisions. - Gutmann and Thompson (2009)

In that view, many social conflicts would be resolved if people were more educated. They would then be more prone to share a common agreement about the most sensible positions. But if reason is a tool we use primarily to convince others, there's no guarantee that higher education levels would yield this result. Instead, it may just make everybody better at arguing about their position.

Motivated reasoning—reasoning so as to form self-serving beliefs—may be constrained by our cognitive skills and the repertoire of ideas we have access to. In her highly cited article on that topic, Ziva Kunda (1990) stated that people’s ability to arrive at the conclusions they want may be “constrained by their ability to construct seemingly reasonable justifications for these conclusions”.

By extending people’s ability to use reason to form arguments, education may actually increase the strength of opposing positions. This possibility has been backed by studies on political beliefs that have found that political polarisation is more pronounced among more educated voters.

In the graph below from Drummond and Fischoff (2017), the polarisation of respondents on different topics increases markedly as a function of their education/cognitive sophistication.

These results also should incite us to be sceptical of the idea that people in disagreement can bridge their divide by “thinking it over”. Instead, taking time to think over your position and how it compares to that of the person you disagree with may help you sharpen your position with better arguments.

This body of evidence explains why people all over the world still widely maintain beliefs that contradict the scientific insights that shape countless aspects of their lives. It is not because they are stupid; it's because being correct about science is often of secondary importance when it comes to achieving social success. When the findings of the scientific community challenge a group's long-held convictions that define its identity1 (e.g., superstition) or threaten its material interests (e.g., advice to discontinue a lucrative practice), members of that group are likely to resist adopting the scientific perspective.

This view about how we use our reasoning abilities should lead us to be more self-reflective about how vindicated we feel that our arguments support our positions. Indeed, we often do not hold these positions because our arguments were strong, but we found these arguments because we favoured these positions in the first place. If we wish to be more honest in our interactions with others, we should practise epistemic vigilance towards ourselves and question whether our views really hold up to scrutiny, or whether we hold them because we want to, and have avoided the tough questions that could lead us to change our minds.

At the level of society, education is unlikely to be the panacea for improving public debates. Indeed, we should be sceptical of solutions aiming to change people. The failings of reason emerge because it is in people’s interests not to be the most rigorous, but the most convincing. Improving public debates requires changing these incentives, which in turn typically requires changing institutions. But that’s a topic for another post.

This post is the second of three posts on how and why our beliefs are wrong but for often good reasons. The previous post looked at the strategic benefits of overconfidence, the next post will look at the coalitional nature of our thinking (what we think is heavily determined by who we side with).

References

Drummond, C. and Fischhoff, B., 2017. Individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on controversial science topics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(36), pp.9587-9592.

Fetterman, A.K., Curtis, S., Carre, J. and Sassenberg, K., 2019. On the willingness to admit wrongness: Validation of a new measure and an exploration of its correlates. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, pp.193-202.

Gutmann, A. and Thompson, D.F., 2009. Democracy and disagreement. Harvard University Press.

Kahan, D.M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L.L., Braman, D. and Mandel, G., 2012. The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change, 2(10), pp.732-735.

Kunda, Z., 1990. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), p.480.

Mercier, H. and Sperber, D., 2011. Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 34(2), pp.57-74.

Mercier, H. and Sperber, D. eds., 2017. The enigma of reason. Harvard University Press.

Rutjens, B.T., Sengupta, N., Der Lee, R.V., van Koningsbruggen, G.M., Martens, J.P., Rabelo, A. and Sutton, R.M., 2022. Science skepticism across 24 countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(1), pp.102-117.

This identity matters in practice, if anything because it justifies the network of social interactions that benefits the group’s members.

I stumbled on this article of yours while I'm writing about the same thing - the interactionist theory proposed by Mercier and Sperber. I'm glad people are writing about their ideas! The book "The Enigma of Reason" changed the way I think about this topic.

> Today, large proportions of the world population do not believe in well-supported scientific concepts like the theory of the Big Bang, biological evolution, or the efficacy of vaccines.

How can an average person without a decent background in astrophysics, evolutionary biology and medical data science know whether these concepts are actually well supported?