Why has the left gentrified?

How shifting social realities and ideological crises reshaped the left

In my previous post, I described the gentrification of the left, placing it within a decades-long process of demographic and ideological change in Western countries. I now turn to the explanation for this pattern. While I draw heavily on existing scholarship, the thesis I propose, grounded in a coalitional perspective, differs from those explicitly1 defended by most social scientists and commentators on the topic.

In their analysis of the growing popular support for right-wing, particularly populist, parties in the West, a trend that has paralleled the gentrification of the left, Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart rightly argue that such widespread developments require general explanations, not ones tied to individual countries:

Nation-specific events […] are proximate causes that help to explain why things worked out as they did within a given country—but they do not explain why the vote for populist parties across many countries has roughly doubled in recent decades. A general theory is needed, to explain this. — Inglehart and Norris (2016)

This post seeks to provide such a general explanation. I argue that two factors lie at the core of this evolution: the erosion of the working class as a large and cohesive electoral bloc due to socio-demographic trends, and an ideological crisis on the left that made left-wing parties more susceptible to ideological drift.

Too many discussions of this question, including by social scientists, begin from a partisan standpoint, judging the evolution as either desirable or regrettable. But starting from a normative position risks biasing our assessment of competing explanations, making it harder to cut through the complexity of events and see what is actually happening. This post seeks to analyse the evolution without passing judgment. It is about why the change happened, not whether it was good or bad.

A realist perspective on the evolution of the left-right ideological opposition

A criticism of existing explanations

"Idealist” explanations: the emergence of new ideas

One explanation for the evolution of the left is that social change has brought about the rise of “postmaterialist values.” The most well-known proponent of this view is Ronald Inglehart, who studied shifts in cultural and political values worldwide. His key idea is that as incomes grew, concerns rooted in economic scarcity and security gave way to issues of self-expression and quality of life.

Cultural change is gradual and generational: the values instilled during childhood persist through adult life, and when societies become more secure over time, younger cohorts tend to grow up with a greater emphasis on postmaterialist values.

— Inglehart, 1997

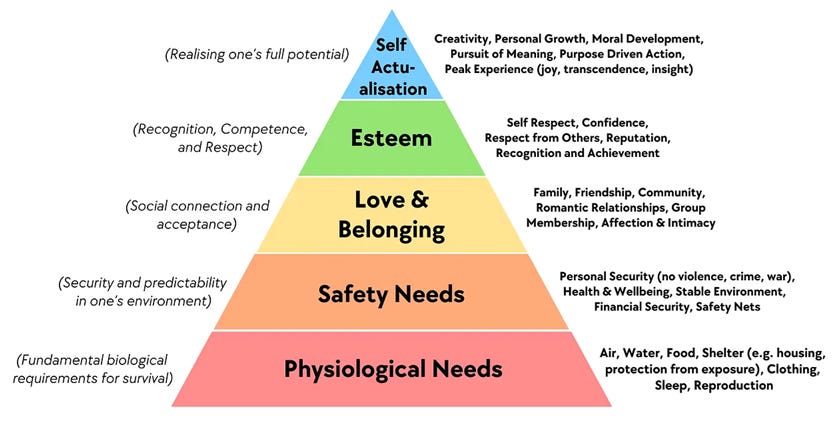

Inglehart’s findings, based on the World Values Survey conducted in up to 80 countries since 1981, are well supported by data. However, his interpretation of the reasons behind this evolution draws on Maslow’s popular pyramid of needs. He suggests that new generations climbed to higher levels of the pyramid, developing new political concerns along the way.

A problem is that this pyramid lacks grounding in modern behavioural science. It presents human needs in a fixed hierarchy, from survival to self-actualisation, and appears disconnected from a psychology grounded in behavioural principles emerging from an evolutionary process.2

Moreover, the theory is too idealistic: higher needs like creativity and meaning do not appear to involve conflicting interests (everyone can pursue them without affecting others). Inglehart’s approach implies that the evolution of political values on the left is autonomous from the material interests of the groups that carry those values. To caricature, it suggests that as we became richer and safer, we all turned a little more into hippies. By contrast, the realist approach I take in this Substack sees ideologies as articulating and rationalising the interests of a social coalition.

Cynical explanation: the betrayal of the left-wing political elite

It is easy to view the gentrification of the left and its shift in political foundations as a “betrayal” of its endeavour to defend the working class. This critique is voiced on popular forums, both by those on the left who regret the change, and by figures on the right seeking to appeal to working-class voters by claiming the left no longer represents them.

In Europe, this argument has been advanced by intellectuals such as historian Perry Anderson, sociologist Wolfgang Streeck, political theorist Chantal Mouffe, and critical theorist Nancy Fraser.3

The social-democratic parties in Europe have abandoned … the struggles of the popular classes. — Mouffe (Interview, 2016)

In the United States, a similar critique has been developed by historian Lily Geismer and Thomas Frank. They argue that the Democratic Party gradually turned away from its working-class base, shifting towards an urban, professional, highly educated electorate.4 Frank (2016) portrays this as a deliberate reorientation by party elites, particularly under Clinton, who embraced market-friendly policies, welfare reform, financial deregulation, and free trade, breaking the party’s traditional alliance with organised labour. The party, in this view, came to reflect the values and interests of professionals rather than the working poor.

A more neutral version of this explanation sees the shift as driven by the “supply side” of politics: left-wing parties changed their political offer to focus more on socio-cultural issues (e.g. feminism, minority rights, and environmentalism). This idea was clearly articulated by political scientists Edward Carmines and James Stimson in Issue Evolution (1989), who argued that partisan alignments shifted as parties introduced new moral and cultural issues into the political agenda. Sociologist Stephanie Mudge also offered a supply-side explanation for the growing economic liberalism of the left. In Leftism Reinvented (2018), she examined the US, the UK, and Germany, arguing that this shift largely stemmed from the growing influence of professional economists and policy experts within left-wing parties, who displaced traditional labour activists and socialist intellectuals.

Political scientists Peter Mair and economist Thomas Piketty also support a supply-side view, though they also consider structural factors such as demographic and educational changes. Still, they stress that party decisions played a key role, and that other choices could have been made. In Capital and Ideology (2020), Piketty traces how key decisions by European left-wing parties led to the adoption of less redistributive policies.5 For instance:

[France] the French Socialists decided in 1984–1985 on a radical change in their economic and political strategy. In the wake of the Single European Act of 1986, they gave in to the demands of the German Christian-Democrats for complete liberalisation of capital flows, which led to a 1988 European directive later incorporated into the Maastricht Treaty of 1992. — Piketty (2020)

[Germany] the SPD decided at its Bad Godesberg convention in 1959 to drop all references to nationalisations and Marxism.

[Poland] Eager to forget the communist past and join the European Union, the Polish Democratic Left Alliance adopted a platform that was social-democratic in name only. Its first priority was to privatise firms and open Polish markets to competition and investment from Western Europe.

In my view, the supply-side explanation has a key limitation. It does not explain why similar choices were made by left-wing parties across the West, not only in Europe, but also in Australia, New Zealand,6 Canada, and the US7. In each case, it is possible to identify pivotal leaders who steered their party toward more market-oriented, less redistributive policies: Tony Blair in Britain, Bill Clinton in the US, François Mitterrand in France, Gerhard Schröder in Germany, Bob Hawke and Paul Keating in Australia, Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin in Canada, Giuliano Amato and Matteo Renzi in Italy, and so on. It seems unlikely that all these leaders independently chose similar paths by coincidence. Rather than treating their choices as fully autonomous, we must examine the common structural constraints and pressures that shaped them.

The coalitional dynamics that have led to the gentrification of the left

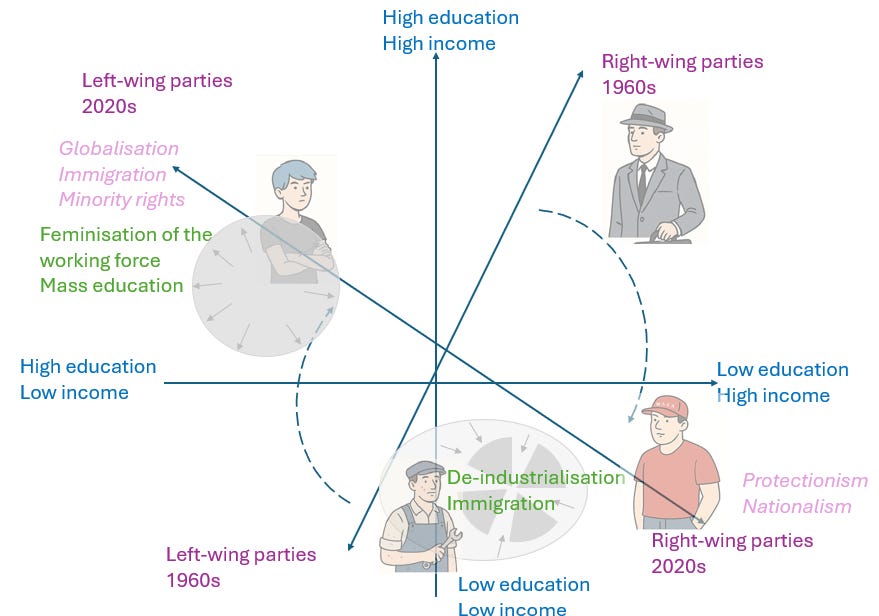

The view I put forward here is that the evolution of the left has been primarily driven by social changes common across Western countries, above all, de-industrialisation and globalisation. These changes have mechanically altered the possibilities for left-wing parties to build successful coalitions of voters. In response, left-wing parties have adapted their political offering, leading to a gradual increase in highly educated voters and a decline in working-class voters in their supporting coalition.

The breakdown of the working class

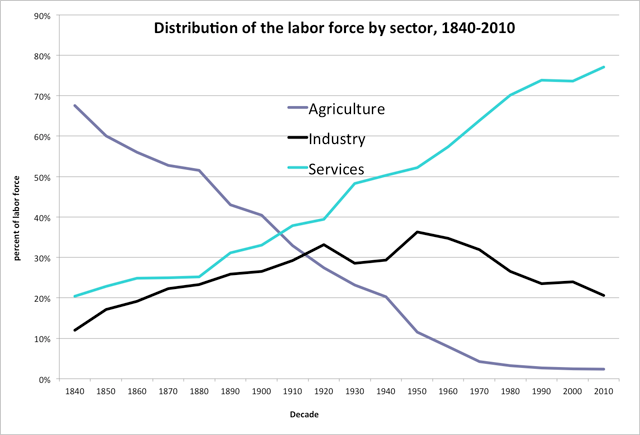

In the postwar period, Western countries had a large share of industry workers, often exceeding 30% of the labour force. These workers were typically employed on large industrial sites, where they were organised by left-wing unions, often closely linked to left-wing parties. This made the working class not only numerous but also politically organised and socially cohesive, united by shared experiences and practices.

Such a group was a natural cornerstone for political coalitions. It is far easier to build a majority starting from a large, organised bloc than from smaller, more fragmented groups.8 Left-wing parties, particularly those with socialist roots, relied on industrial workers as the backbone of their coalitions.

Since then, de-industrialisation has steadily eroded this foundation. The number of industrial workers has declined, and many low-wage workers have moved to small workplaces (such as fast food outlets), where they are less likely to be unionised. This has reduced the cohesion of low-income voters, both in their everyday experiences and in their political organisation, making it harder to secure their support as a bloc.

The rise of mass unemployment in Europe from the 1970s further fragmented low-income groups by pushing a large share of them out of the labour force, sometimes creating conflicting interests with workers in stable, protected jobs.

In addition, many Western countries have seen a steady flow of immigration from lower-income countries since the 1960s, often to meet the demand for low-skilled labour in industry. As a result, a significant share of lower-income earners today have different national origins from native-born workers. This fact creates the potential for new divisions within the working class along cultural or national lines, weakening the unifying role of occupational identity.9

The emergence of new groups with different priorities

Alongside the fragmentation of the working-class bloc, two major social transformations have led to the rise of new groups.

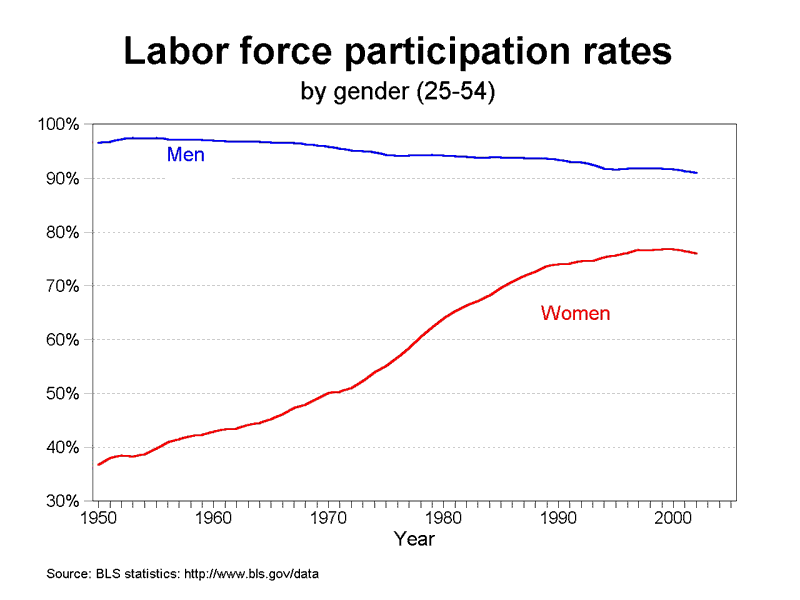

The first is the feminisation of the labour force. While women have always worked, Western countries have seen a marked increase in women’s access to paid employment in the second part of the 20th century. This shift brought greater economic independence, which translated into increased bargaining power within both households and society. Women gained the right to work and open a bank account without their husbands’ consent in 1965 in France and 1977 in Germany. Gender discrimination in the workplace was gradually reduced in the second half of the 20th century. These changes aligned women’s interests more closely with left-wing parties, which traditionally supported reforms challenging the existing social order. As a result, whereas women once voted more conservatively than men, they have progressively shifted left.

This feminisation of the left also influenced its policy focus. Women’s professional lives often differ from men's, with greater representation in services, education, care, and health. The political concerns of working women therefore diverged from those of the archetypal male factory worker who had long anchored the left's coalitions.

The second transformation is the rise of mass education. The expansion of the service economy and the growing need for technical skills have led to a sharp rise in university attendance, now exceeding 50% in many Western countries. Students occupy the high-education, low-income end of the social space. Though their turnout is lower, their growing numbers make them an attractive group for coalition-building. Young people also tend to be more open to change, making them a natural constituency for left-leaning parties. Here again, the priorities of students and higher-educated youth are not fully aligned with those of industrial workers. Their distinct experiences and concerns promoted new issues into the political agenda of left-wing parties, often different from, and at times in tension with, the traditional preoccupations of the working-class base.

Mass education hasn’t just increased the overall number of university graduates, it also likely plays a role in political socialisation. At university, students are exposed to a cultural environment that tends to be left-leaning. They are also surrounded by peers who are more likely to hold progressive views. This environment may contribute to shaping support for left-leaning parties later in adulthood among highly educated voters.10

This is particularly true among highly educated voters who do not move into high-paying careers. This includes, for instance, civil servants, teachers, journalists, artists, and people in the non-profit sector. These voters provide a potential base of support for left-leaning parties that back socio-cultural change and a degree of economic redistribution. Their middle-class circumstances, however, make them favour redistribution that is less radical than the programmes championed by working-class-led parties in the early twentieth century.11

The weakening of economically leftwing ideologies

The final set of changes occurred in the ideological space. Ideologies are tools for coalition-building, offering a shared vision of the social contract. Those that are conceptually coherent are more likely to succeed in attracting diverse groups who believe in their viability in case of political victory.

In the early 20th century, Marxism offered a compelling ideology. Rooted in a “science of history”, it presented communism as a necessary outcome. Marx’s dialectical materialism claimed that capitalism’s internal contradictions would inevitably cause its collapse and replacement by collective ownership of production.

While the West reeled from the 1929 crash and the crises of the 1930s, Russia’s rapid industrialisation made communism appear economically successful. It is easy today to overlook the strength the Soviet model seemed to project. In his 1961 textbook Economics: An Introductory Analysis, Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson noted that Soviet growth outpaced the U.S., predicting its GNP could surpass that of the U.S. between 1984 and 1997.12

In that context, communism offered a compelling and teleological ideological framework. It seemed like the natural cause for the working class, promising to turn the tables on the economic elite of their countries.

However, the glow of the communist ideology progressively faded. Politically, the ideals of progress and liberation were contradicted by emerging evidence of totalitarianism under Soviet rule. The suppression of dissent in the Eastern bloc in 1956 (Hungary) and 1968 (Czechoslovakia) further eroded its legitimacy. The collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989 marked the final blow. The proof of the pudding is in the eating: the communist model failed, not just politically but economically.

This left socialist parties without a guiding conceptual framework. Today, political philosophy textbooks typically include chapters on utilitarianism, Marxism, liberalism, libertarianism, and communitarianism, but not a distinct chapter on socialism. With Marxism discredited, there was not a fully fledged alternative socialist doctrine to take its place.

Parties with socialist foundations in Europe ended up adopting moderate positions as a de facto compromise without consistent ideological principles. They came to embrace democracy, despite Marxism's earlier scepticism of democratic institutions, dismissed as bourgeois. They came to accept capitalism and markets in their policies, even though they retained official narratives often critical of capitalism and markets. The members of the French Socialist Party still sang the communist anthem The Internationale until 2010, even as their presumed presidential candidate was the de facto quite liberal economist Dominique Strauss Kahn, who headed the IMF.13

Social democrat parties that had already distanced themselves from Marxism, such as Germany’s SPD fared somewhat better.14 The SPD officially accepted capitalism and market mechanisms as early as 1959 in its Bad Godesberg convention.15

Parties that were never fully aligned with the Marxist tradition, such as the Labour parties in Britain and Australia, or the Democratic Party in the US, were less directly affected by the ideological decline of communism. Yet these moderate left-wing parties often lacked a clearly defined ideological corpus. Their platforms tended to reflect pragmatic compromises between socialist and liberal ideas, with few foundational principles to guard against ideological drift toward more centrist or market-oriented positions.

The ideological woes of the left were compounded by the fact that the alternative moderate economic theory to defend redistribution and state intervention, Keynesianism, appeared to systematically fail to work in the 1970s. Popular in social democratic parties and in the US Democratic party, Keynesianism purported to solve unemployment by increasing government spending. However, after the petrol crisis of 1973, the attempt to support the economy with government spending failed to bring down unemployment and instead caused stagflation (unemployment plus inflation). In the UK, Labour governments in the 1970s struggled to reduce unemployment through Keynesian policies, which were repeatedly followed by austerity measures aimed at controlling inflation. This cycle of “stop-go” economics ultimately failed to deliver stability, contributing to growing disillusionment and paving the way for Margaret Thatcher’s right-wing economic revolution.

To understand the political evolution of the left, one must recognise that by the 1980s it was on the ideological back foot in economic matters, a stark contrast to the 1930s and 1950s, when left-wing ideologies appeared to offer credible solutions to the world’s problems.

Globalisation made things worse by reducing the feasibility of left-wing economic policies. Wealth and capital became highly mobile. Any increase in income tax risked prompting high earners to move abroad, while higher corporate taxes could incentivise firms to relocate their headquarters to lower-tax jurisdictions.16 A well-known result from Roger Gordon (1986) showed that in open economies, mobile sources of income like capital tend to be taxed less heavily than less mobile ones like labour. In short, globalisation made it harder to tax wealth than to tax work.

Globalised financial markets also made governments accountable not only to their voters but also to investors, who continuously assess whether a country’s policies are likely to support long-term economic stability. When markets lose confidence, capital exits and currencies come under pressure, creating a politically and economically unmanageable situation. As a result, left-wing governments have often faced a “wall of money” that constrained their ability to implement redistributive policies. A classic case is France in 1981: elected on a joint platform with the Communist Party, the Socialist government soon faced capital flight, pressure on the franc, and market backlash. By 1983, it had to abandon much of its programme and pivot to austerity.17

As left-wing ideologies faced mounting crises in the latter half of the 20th century, especially on economic issues, left-wing parties became increasingly porous to new ideas. In this context, socio-cultural issues outside the economic domain offered a valuable alternative battleground. As these parties struggled to implement their economic programmes and grew uncertain about their effectiveness, causes like women’s rights, gay rights, and minority rights emerged as useful substitute arenas where conservative parties could still be challenged and defeated.

A socio-economic evolution articulated on an ever-present coalitional challenge for socialist parties

In their influential 1986 book Paper Stones, political scientists Adam Przeworski and John Sprague argued that socialist leaders in Europe faced a coalitional dilemma from the outset: a purely worker-based appeal was insufficient to secure electoral majorities. Across fourteen Western European countries, they found that industrial workers “never were and never would become” a numerical majority, and socialist vote shares routinely stalled at what they called the “magic barrier” of around 40–50 per cent of the electorate.

Once parties reached that ceiling, they faced a trade-off: they could try to broaden their coalition to include clerks, smallholders, or salaried employees, but only at the risk of weakening their support among workers.

Socialist parties had to seek allies who would join workers under their banner if they were to be effective in elections at all […] The dilemma appears at this moment. When socialists seek to be effective in electoral competition they erode exactly that ideology which is the source of their strength among workers — Przeworski and Sprague (1986)

The cohesion and size of the working class led many socialist parties to opt for staying “classpure”.18 But as de-industrialisation and mass education reshaped the social and electoral map, the costs of not adapting became higher for left-wing politicians seeking power. What Przeworski and Sprague wrote nearly 40 years ago helps explain the steady gentrification of the left since the postwar period:

The post- 1945 orientation of several parties is not a result of a new ideological posture but rather a reflection of the changing class structure of Western Europe. […] The new middle classes replaced the old ones […]. Party strategies reflected, with some lag, the numerical evolution of the class structure. — Przeworski and Sprague (1986)

These various mechanisms help explain what has happened since the 1960s. The solid base of industrial workers shrank and fragmented, while new groups, working women and university students, emerged as potential support for left-wing parties. These groups were often inclined to challenge the social order and offered natural constituencies for parties seeking to rebuild their coalitions. At the same time, the strong ideological coherence once provided by Marxism faded, leaving left-wing parties without clear principles that might have constrained their adaptation to the concerns of these new supporters. In the next post, I will explore how these developments also help account for the concurrent rise in popular support for right-wing parties.

References

Anderson, P. (2009) The New Old World. London: Verso.

Berman, S. (2006) The Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Making of Europe’s Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Campbell, C. and Horowitz, J., 2016. Does college influence sociopolitical attitudes? Sociology of Education, 89(1), pp.40–58.

Campbell, C. and Horowitz, J. (2016) ‘Does college influence sociopolitical attitudes?’, Sociology of Education, 89(1), pp. 40–58.

Felsenthal, D.S. and Machover, M. (2002) ‘Annexations and alliances: When are blocs advantageous a priori?’, Social Choice and Welfare, 19, pp. 295–312.

Fraser, N. (2017) ‘The end of progressive neoliberalism’, Dissent, 64(2), pp. 41–49.

Frank, T. (2016) Listen, Liberal: Or, What Ever Happened to the Party of the People? New York: Metropolitan Books.

Geismer, L. (2015) Don't Blame Us: Suburban Liberals and the Transformation of the Democratic Party. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gethin, A., Martínez-Toledano, C. and Piketty, T. (2022) ‘Brahmin left versus merchant right: Changing political cleavages in 21 western democracies, 1948–2020’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(1), pp. 1–48.

Golder, S.N. (2006) ‘Pre-electoral coalition formation in parliamentary democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 36(2), pp. 193–212.

Gordon, R.H. (1986) ‘Taxation of investment and savings in a world economy’, American Economic Review, 76(5), pp. 1086–1102.

Inglehart, R. (1997) Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R.F. and Norris, P. (2016) ‘Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have-nots and cultural backlash’, HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series, RWP16-026. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Kennedy School.

Leech, D. (2005) ‘Voting power and voting blocs’, Public Choice, 122(1–2), pp. 183–208.

Leone Sciabolazza, V. (2022) ‘Bargaining within the Council of the European Union: An empirical study on the allocation of funds’, Italian Economic Journal, 8(2), pp. 227–258.

Magness, P.W. and Makovi, M., 2023. The Mainstreaming of Marx: Measuring the effect of the Russian Revolution on Karl Marx’s influence. Journal of Political Economy, 131(6), pp.1507-1545.

Marx, K. (1870) ‘Letter to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt, 9 April 1870’, in Marx, K. and Engels, F. Collected Works, Vol. 43. London: Lawrence & Wishart, pp. 472–475.

Maslow, A.H. (1943) ‘A theory of human motivation’, Psychological Review, 50(4), pp. 370–396.

Mair, P. (1997) Party System Change: Approaches and Interpretations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McBride, S., & Whiteside, H. (2011). Private Affluence, Public Austerity: Economic Crisis and Democratic Malaise in Canada. Fernwood Publishing.

Mouffe, C. (2018) For a Left Populism. London: Verso.

Mudge, S.L. (2018) Leftism Reinvented: Western Parties from Socialism to Neoliberalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Piketty, T. (2020) Capital and Ideology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Redden, G., Phelan, S. and Baker, C. (2020) ‘Different routes up the same mountain? Neoliberalism in Australia and New Zealand’, in Dawes, S. and Lenormand, M. (eds) Neoliberalism in Context: Governance, Subjectivity and Knowledge. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 61–82.

Samuelson, P.A. (1961) Economics: An Introductory Analysis. 6th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Shayo, M. (2009) ‘A model of social identity with an application to political economy: Nation, class, and redistribution’, American Political Science Review, 103(2), pp. 147–174.

Streeck, W. (2016) How Will Capitalism End? Essays on a Failing System. London: Verso.

Tørsløv, T., Wier, L. and Zucman, G. (2023) ‘The missing profits of nations’, The Review of Economic Studies, 90(3), pp. 1499–1534.

I put “explicitly” here, because some accounts of the gentrification of the left can be reinterpreted as compatible with the coalitional mechanism I describe here. There is considerable overlap between the factors I highlight and those discussed by Piketty, for instance. The key difference lies in my emphasis on how socio-economic changes led to changes in political coalitions.

I have written several posts on naturalistic explanations of our drive for happiness and meaning. The idea that self-actualisation—an intrapersonal feeling—sits at the top of a universal pyramid of needs is difficult to reconcile with the view that our needs evolved to help us succeed in the real world (survive, have surviving offspring) and progress through the intermediate steps required to do so (secure resources, find a mate, gain supportive allies).

This is why I find the idea that shifts in societal values result from people becoming richer in absolute terms unconvincing. As countries grow wealthier, those at the bottom still experience frustration due to their relative position. Happiness is largely determined by one’s place on the social ladder, not just absolute income.

Anderson (2009), Streeck (2016), Fraser (2017), Mouffe (2018)

Geismer (2014), Frank (2016).

In a 2022 paper, Piketty and co-authors suggested that party decisions have shaped the new left–right divide by elevating socio-cultural issues. They called for further work to measure the causal impact of political supply on these shifts:

A promising avenue for future research lies in establishing more directly the causal impact of political supply on the transformation of political cleavages. — Gethin et al. (2022)

See Redden, Phelan, and Baker (2020)

See Frank (2016), Geismer (2014), and McBride & Whiteside (2011).

In coalitional game theory, a group’s bargaining power refers to its capacity to form a winning coalition. The Shapley value is a formal measure of this power. While it can theoretically fall when a group becomes larger, studies have shown that blocs have higher Shapley value and higher payoffs in the case of parties bargaining to form a government (Golder, 2006), countries bargaining for the EU budget (e.g. Leone Sciabolazza, 2022), and shareholders voting in companies (Leech, 2005).

Political scientist Moses Shayo (2020) offered a theoretical account of why people may choose group identities not only for cultural affinity but also for social status. For many working-class individuals, identifying as nationals may carry more symbolic prestige than class identity. This may lead them to support policies like immigration restrictions that reinforce national belonging, even if these policies were to actually offer little direct material benefit.

See, for instance, the study by sociologists Campbell and Horowitz (2016) on the likely effect of university education on the adoption of more left-leaning positions.

On this “Brahmin left” (highly educated left-wing voters), Piketty writes:

The Brahmin left may prefer somewhat higher taxes than the merchant right: for instance, to pay for the lycées, grandes écoles, and cultural and artistic institutions to which it is attached. But both camps are strongly attached to the existing economic system and to globalization as it is currently organized, which ultimately serves the interests of both intellectual elites and economic and financial elites. — Piketty (2020, p. 773)

In fact, it is possible that the Bolshevik revolution in Russia is what gave Marxism its historical preeminence on the left in the West. At the turn of the 20th century, Marxism also faced a credibility problem, and, strikingly, the same political alternatives as today rose up. Here is what political scientist Sheri Berman wrote about it:

Around the turn of the twentieth century, therefore, many on the left faced a troubling dilemma: Capitalism was flourishing, but the economic injustices and social fragmentation that had motivated the Marxist project in the first place remained. Orthodox Marxism offered only a counsel of passivity – of waiting for the contradictions within capitalism to bring the system down, which seemed both highly unlikely and increasingly unpalatable. […] The forward march of markets had caused immense unease in European societies. Critics bemoaned the glorification of self-interest and rampant individualism, the erosion of traditional values and communities, and the rise of social dislocation, atomization, and fragmentation that capitalism brought in its wake. As a result, the fin-de-siècle witnessed a surge in communitarian thought and nationalist movements that argued that only a revival of national communities could provide the sense of solidarity, belonging, and collective purpose that Europe’s divided and disoriented societies so desperately needed. — Berman (2006)

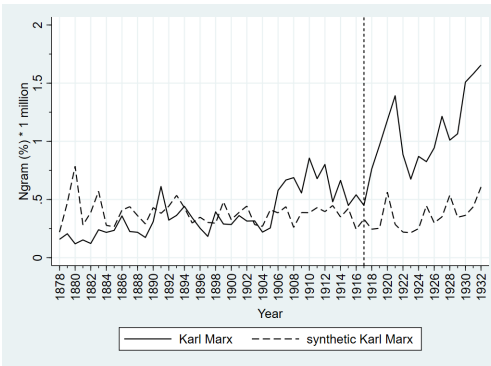

A recent paper in economic history by Magness and Makovi (2023) showed the impact of the Russian revolution on Marx's cultural influence by comparing the evolution of his citation to a “synthetic” control (a fictitious writer made as an aggregation of writers similar to Marx before the Russian revolution.

Their uncertain ideological ground is also illustrated by a famous statement from their leader Lionel Jospin during the 2002 presidential campaign. He declared that while he was a socialist, his political project was not. He did not seek to transform capitalism but to regulate it. This statement is often seen as contributing to his failure to reach the second round, losing narrowly to far-right leader Jean-Marie Le Pen.

Sheri Berman (2006) wrote a very interesting history of social democracy in Europe in the 20th century. While she did not focus on the coalitional dimensions of ideology, her analysis of ideological supply and demand complements the ideas explored in my earlier post on political ideas.

The different political trajectories of the socialist movement in Germany and France can also be understood through coalitional dynamics. In West Germany, the banning of the Communist Party in 1956 left the Social Democratic Party (SPD) as the sole representative of the working class, giving it the strategic freedom to redefine its platform. This culminated in its formal break with Marxism in the 1959 Bad Godesberg Program. In contrast, in France and Italy, large Communist parties regularly secured 25–30% of the vote, acting as ideological anchors on the left. Socialist parties in those countries could not entirely disavow Marxist rhetoric without jeopardising electoral cooperation to gain power. This constraint explains the tension between their often radical public positions and narratives and the more moderate policies they implemented once in office.

Indeed, international firms frequently optimise accounting to shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions, even where they have little or no real activity. For instance, a company may assign ownership of trademarks or intellectual property to a subsidiary in a tax haven. Other parts of the firm then pay large fees or royalties to that subsidiary, allowing the group to report higher profits where taxes are lowest. For an overview of the scale and consequences of such strategies, see Tørsløv, Wier, and Zucman (2023).

A comparable fate befell British PM Liz Truss in 2022, when she proposed a mini-budget with large tax cuts for high earners. Financial markets reacted with alarm, triggering a fall in the pound and a surge in bond yields. Within weeks, the policy was reversed and Truss resigned after just 45 days in office.

Staying “classpure” limits the opportunity to reach a majority. The history of the British Labour Party offers an illustration of this dilemma. The Labour Party’s return to more explicitly socialist rhetoric under Michael Foot’s leadership, beginning in 1980, prompted a breakaway by centrist Labour MPs. In 1981, they founded the Social Democratic Party (SDP), which aimed to appeal to middle-class and professional voters disillusioned with Labour’s leftward turn. The SDP later merged with the Liberal Party in 1988 to form the Liberal Democrats, a centrist party that remains a small but significant party in British politics.

The move by Tony Blair to “New Labour,” which formally abandoned the reference to common ownership, marked a shift to the centre and a successful attempt to build a broader coalition beyond the working class. The Labour party became electorally dominant by appealing to middle-class and professional voters while maintaining redistributive commitments.

This is a very interesting article about an exceptionally important topic. I believe that what you call the "Gentrification of the Left" is one of the most important trends of the last 60 years.

I am not sure, however, that I am convinced by your argument.

The decline of the traditional factory working class does not necessarily present problems for parties of the Left maintaining their social coalition. There were still plenty of service workers with below-average income and education to appeal to with economically distributive policies. And there still are.

And women did not tilt heavily left until quite recently.

If you look at it historically, one can see a large expansion in the support for the parties of the Left among the highly educated young people in the late 1960s, with the Baby Boomers coming to age. Those people chose to join the Left long before these long-term trends that you mention in this article were fully in effect.

Those Baby Boom activists on the Left brought with them a concern for a very different type of inequality: race, gender, plus environmentalism and anti-militarism. Those activists gradually worked their way up the organization of Leftist parties and gradually changed what Leftism meant.

In the following decades, working-class voters reacted to this by gradually leaving Left parties. This reinforced the hold of affluent activists over the party organization, thereby reinforcing the trend.

Party leaders tried hard to balance the view of the two coalition, but the activists who worked their way up the party were invariably college-educated professional, so their views took precedence.

There is no fundamental reason why Left parties could not have combined redistributionist economic policies plus more traditional cultural views. That is, in fact, what much of the so-called Populist Right that is growing so strongly now advocates for.

So the Gentrification of the Left is not about parties looking for new social coalition as much as a relatively small group of activists gradually capturing the party and reorienting policy platforms towards their views. Then voters react to that as the change becomes obvious over repeated election campaigns.

I admit that this theory does not explain why the affluent activists and professional-class voters became Left in the first place, but it does better fit with the history of how parties of the Left have changed over the last 60 years. The trend were created by activists, not demographic change.

Great post, Lionel. Looking forward to the next one in this series You should collect your posts in a book!