The gentrification of the left

And the popularisation of the right in Western countries

I continue to discuss practical political dynamics using insights from coalitional game theory and psychology. Here, I address a major phenomenon in Western countries: the gentrification of the left and the popularisation of the right. This post builds on two ideas I have previously discussed. First, political coalitions are much more flexible than we tend to think. Second, political ideologies serve as a coalition-binding tool.

The terms “left” and “right” come from the French Revolution. In 1789, members of the National Assembly who supported radical change and the end of feudal privileges sat on the left. Those who defended the monarchy and the old order sat on the right. This spatial division became a shorthand for political allegiance.

Over time, the left became associated with change, seen either as progress or disruption, depending on one’s perspective, and the right with the preservation of the existing order. The advent of socialism in the 19th century and the rise of a large organised working class in Western democracies led the left to represent low-income groups and their demands for a fairer distribution of social resources. However, this pattern has shifted in recent years with a demographic reversal. In many countries, right-wing parties now often enjoy broader popular support than their left-wing counterparts. This reversal has also come with a notable evolution in the political ideas advanced by left-wing parties.

The arbitrary and flexible nature of political coalitions' ideology

The left–right opposition suggests that political ideologies naturally align along a single continuum, from the extreme left to the extreme right. To understand someone’s political position, it is then sufficient to locate them on this line. However, this one-dimensional opposition is misleading. Political positions on various issues do not necessarily correlate perfectly with one another. The left–right dimension is historically associated with a preference for greater redistribution (left) versus resistance to state intervention in the economy (right). But it is not clear a priori why this dimension should predict positions on every political topic.

Consider, for instance, three salient topics: women’s rights, religious freedom, and nuclear energy. There are historical and international variations in how different issues have aligned with the left and the right. Regarding women’s rights, many socialists in early 20th-century France opposed women’s suffrage because women were seen as more religious and conservative.1 On the topic of religion, the left has traditionally opposed it, viewing religion as part of the conservative order. Left-wing parties in Europe often adopted a militant secularism aimed at reducing the influence of religions and their formal institutions in the public sphere. Today, however, many left-wing parties have shifted toward defending the rights of minority religions and advocating for public space to accommodate their practices.2 As for nuclear energy, left-wing positions vary by country: in the United Kingdom, the left tends to support it; in Germany, the left tends to oppose it.

To understand the messy nature of political ideology, one must think of political space as multidimensional: each political issue generates its own dimension, with positions for or against it.3 In such a space, there may be some correlation in people’s positions, and a reasonable assumption is that the left–right dimension represents the main axis of opposition.4 However, the game theory of politics suggests that we cannot rely on this “natural” definition of left and right. In politics, coalitions compete for power, and politicians compete to propose ideological bundles capable of attracting a large enough coalition to win. According to economist Richard McKelvey’s “chaos theorem,” in a multidimensional political space, a majority vote can lead to virtually any point through a sequence of decisions.5 This implies that the ideological bundles that prevail can shift over time.6

The evolution of the left-right opposition in the political space

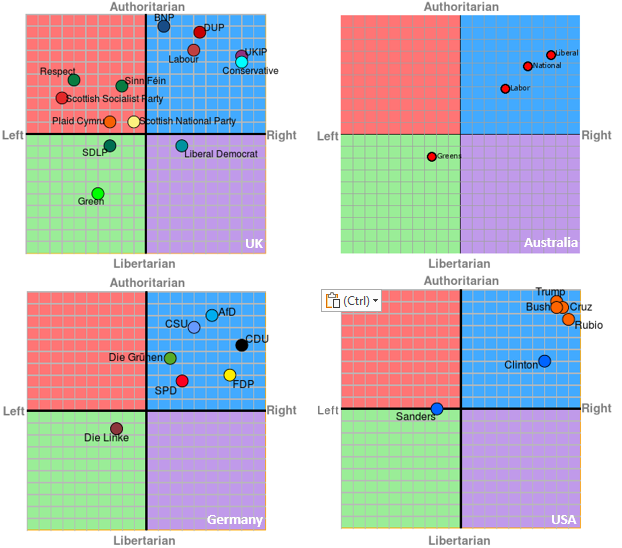

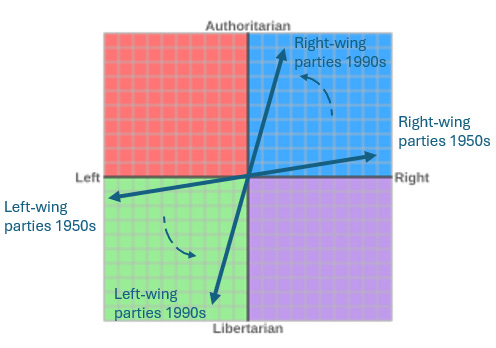

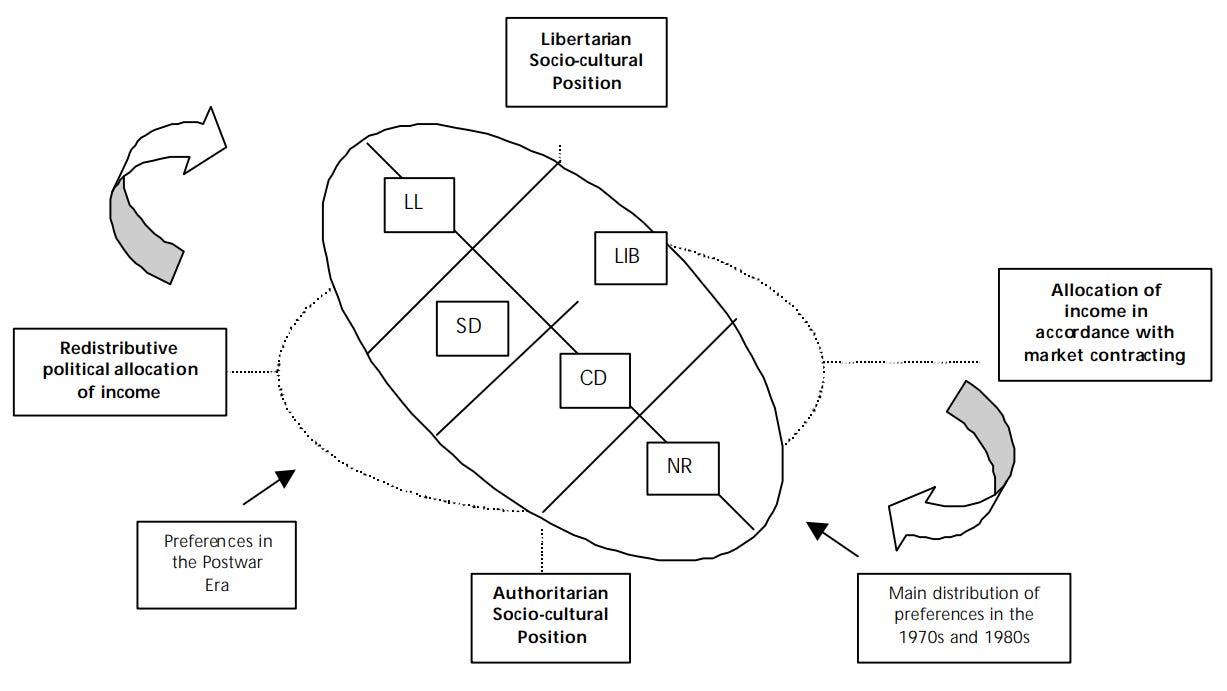

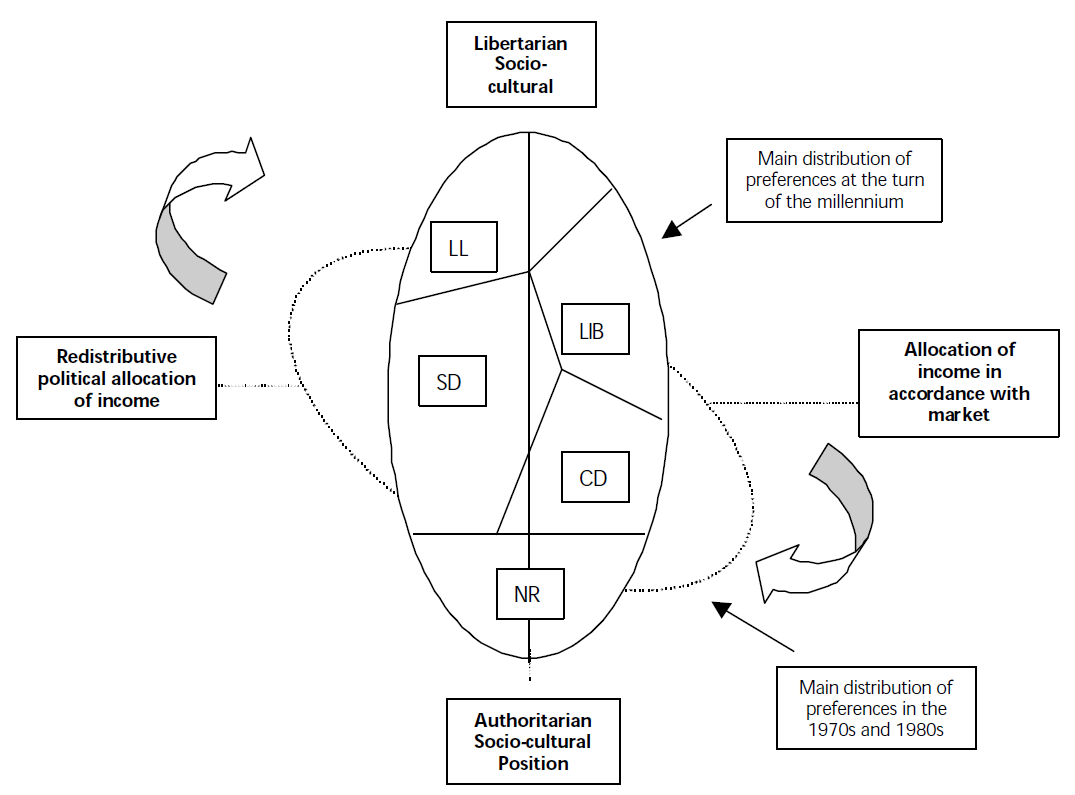

The fact that political space is multidimensional is reflected in a popular representation of political positions using a two-dimensional grid, where the horizontal axis captures preferences for or against economic redistribution, and the vertical axis reflects preferences for a more or less free society.7 The “political compass” has become a common way to represent these two dimensions, and online tests are easy to find to help you locate yourself within this space.

Applying these tests to the positions of major parties in Western countries shows that the left–right dimension generally extends from the left-libertarian to the right-authoritarian quadrant.

The historical transformation of the left

It is clear that the ideological makeup of the left has changed in recent years. Redistributive issues have declined in importance, while “cultural” issues have gained prominence, particularly through a growing focus on the rights and outcomes of women and minority groups. The so-called “Great Awokening” of the late 2010s made this evolution especially visible and widely discussed.

However, this shift reflects a much longer-term trend. Thirty years ago, in 1994, political scientist Herbert Kitschelt published The Transformation of European Social Democracy, in which he described how the left–right opposition had gradually evolved over time.

Using the same dimensions as those in the political compass, he showed that from the postwar era to the 1990s, the left–right axis had gradually shifted from a primarily economic opposition, between redistribution and laissez-faire, to one increasingly based on socio-cultural issues.8

In that long-term perspective, the great awakening of the 2010s is not a one-off event. It is rather the continuation of a decades-long trend, with cultural issues gaining prominence in the left-right opposition.

The evolution of the leftwing coalition

In a little-known 2003 article published in a French intellectual review, economist Thomas Piketty discussed the results of a study he conducted in 1998 on political attitudes in France. He observed that the main line of political opposition was no longer centred on the level of inequality, as views on this issue were relatively similar across the political spectrum. Instead, cultural issues had become the primary source of division.

The reduction of income differences does not appear to be a crucial issue for the usual French political conflict […] the fact that individuals who place themselves on the far left of the political spectrum seem to favour roughly the same socially optimal level of inequality as those who identify with the right wing was a surprise to me […] the survey questions on the death penalty, the role of women, foreigners, or the issue of globalisation seem to characterise the nature of the left/right conflict much better than questions on income inequality or redistribution. — Piketty 2003 (my translation, emphasis mine)

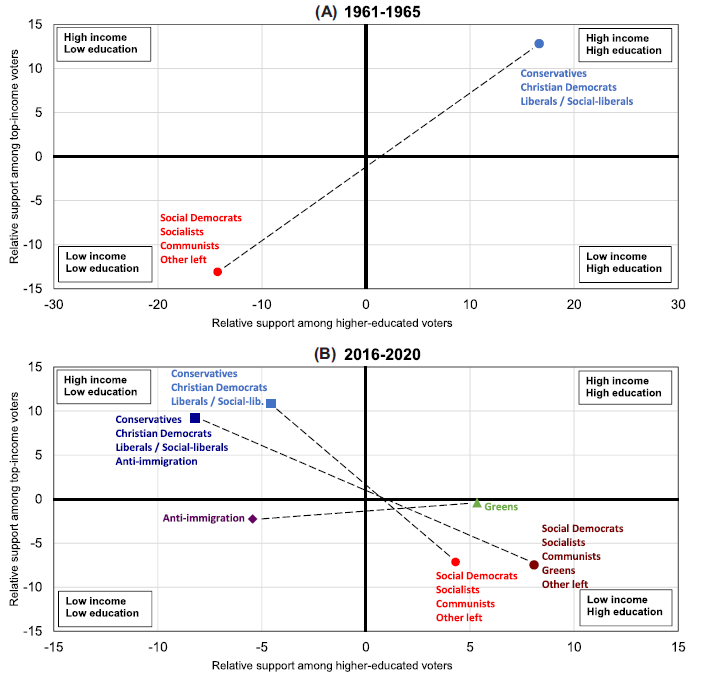

Piketty had found a result similar to that of Kitschelt, whom he cited at the time. Twenty years later, Piketty published evidence that a demographic shift was accompanying this political evolution, not just in France but in other Western countries too. From the postwar era to the 2010s, support for left-wing parties progressively gentrified, with highly educated voters increasingly voting more for the left than less educated voters.

The popularisation of the right

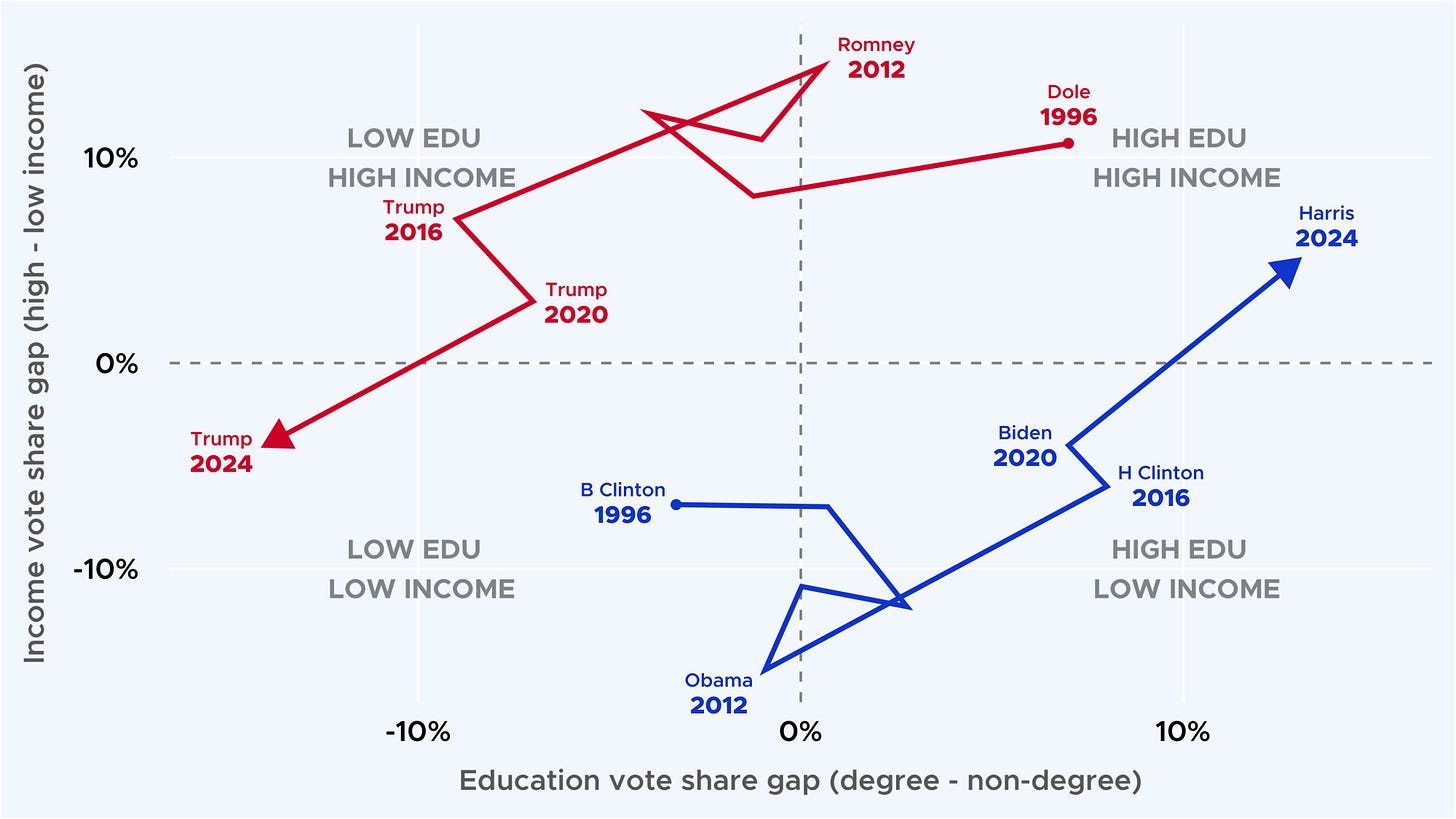

Recently, U.S. data journalist Patrick Flynn created an infographic that went viral on Twitter, illustrating how the demographic evolution of the left has been mirrored on the right, leading to Democratic and Republican candidates to nearly swap electorates over time. Trump’s coalition in recent years resembles Clinton’s in 1996, drawing support from lower-education and lower-income individuals.

Here again, this evolution is not limited to the U.S. Piketty and his co-authors found that, in the space defined by education and income, the left–right opposition has rotated across Western democracies. In the postwar era, high-income and highly educated voters were the most likely to support the right. Today, the right tends to attract lower-education voters, and in some cases, even lower-income voters.

This popularisation of the right has been illustrated by significant electoral outcomes in recent years beyond the U.S. In 2019, the British Conservatives won many seats in Labour’s “Red Wall”, constituencies in the Midlands and Northern England with traditionally working-class electorates. In France, Marine Le Pen was in 2022 the most popular candidate among workers.

The articulation of the change of ideology and the change in coalition underlying leftwing parties

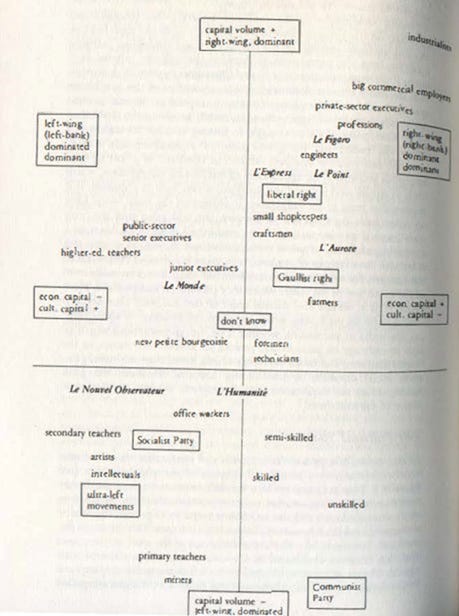

Piketty’s use of the conjunction of education and income to map changes in support for left- and right-wing parties echoes sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s emphasis on wealth and education as structuring social life, shaping who interacts with whom, and who thinks, consumes, and enjoys what. In his highly influential book Distinction, Bourdieu showed that wealth and education, and whether you have a lot of both, or more of one than the other, strongly influence social relationships and tastes.9

For Bourdieu, this two-dimensional space is relevant for thinking about political coalitions, as it reflects the relative distance between social groups in terms of common activities and interests.10 He found that in the 1960s, the left–right opposition in France was mostly between voters with high education and high income (right) and voters with low education and low income (left). The change observed by Piketty corresponds to a rotation of that opposition within this space, leading to an evolution of political coalitions, with the left attracting more highly educated, low-income voters, and the right drawing more low-educated, high-income voters.11

Ideologies are not just abstract systems of ideas, they help articulate a coalition whose interests they reflect. It is therefore not surprising that the evolution of the left’s ideological foundations has paralleled a shift in its demographic base. As its base has moved toward urban, educated voters, left-wing parties have shifted their focus from economic redistribution to cultural issues more in line with the preferences of this new part of their social coalition.

The left has undergone a noticeable process of gentrification in Western countries. This process appears to be general, and therefore not reducible to specific national factors. Commentators often blame individual politicians for ideological shifts, but these shifts reflect broader social changes that cut across national contexts. In short, this gentrification should not primarily be attributed to decisions by individual politicians like Bill Clinton in the US or Tony Blair in the UK. The politicians who carried this evolution seem to have followed strong underlying social trends that transcend substantial differences in political culture and political competition across countries. The evolution of political coalitions in Western democracies, therefore, calls for general explanations, which I’ll discuss in my next post.

References

Atkinson, W., 2021. The social space and misrecognition in 21st century France. The Sociological Review, 69(5), pp.990–1012.

Bennett, T., Savage, M., Silva, E., Warde, A., Gayo-Cal, M. and Wright, D., 2009. Culture, Class, Distinction. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P., 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Originally published in French in 1979)

Currid-Halkett, E., 2017. The Sum of Small Things: A Theory of the Aspirational Class. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gethin, A., Martínez-Toledano, C. and Piketty, T., 2022. Brahmin left versus merchant right: Changing political cleavages in 21 western democracies, 1948–2020. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(1), pp.1–48.

Kitschelt, H., 1994. The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kitschelt, H., 2003. Diversification and Reconfiguration of Party Systems in Postindustrial Democracies. Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Available at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/02608.pdf [Accessed 30 May 2025].

Lamont, M., 1992. Money, Morals, and Manners: The Culture of the French and the American Upper-Middle Class. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Piketty, T., 2003. Attitudes vis-à-vis des inégalités de revenu en France: existerait-il un consensus? Comprendre, 3(1), pp.103–139.

Sowerwine, C., 1982. Sisters or Citizens? Women and Socialism in France since 1876. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Here is a long quote from Charles Sowerwine’s history of socialism and feminism in France, offering a valuable historical insight into the mindset of French socialists at the beginning of the 20th century:

Women's suffrage was beyond the pale of practical politics, unlikely to be realised and still less likely to interest voters. Electoral statements of socialist candidates rarely mentioned women. Apart from general party programmes—and even these were occasionally doctored to leave out women's rights—only one or two socialists mentioned women's suffrage in their individual programmes for each election.

Not only did socialists avoid the issue of the suffrage, but also some actually opposed women's suffrage, fearing that women would bring the clerical influence out of the confessional and into the voting booth. After the international socialist congress of Stuttgart in 1907, the socialist deputy Bracke wrote that, despite the quasi-unanimity obtained in the vote on the resolution for women's suffrage, he found in the corridors 'the old arguments that stop more than one comrade at the moment of action. Women's suffrage, to be sure! But later, when they've been educated.' Even many feminists, following in Richer and Deraismes's tradition, thought it advisable to leave women's suffrage aside until the question of proportional representation was settled.

Thus it was that in 1906, as we shall see, the party voted to present a bill for women's suffrage which was never written and that in 1907 the SFIO deputies named a sub-committee on women's rights which never met. — Sowerwine (1982)

This shift explains the fate of the New Atheists, intellectuals like Hitchens, Dawkins, and Harris, who militantly opposed religious (mostly Christian) ideas in the early 2000s. They were later rejected by large parts of the left in the 2010s when they applied the same uncompromising attitude to Islam. Similarly, in France, the historically left-libertarian and anti-clerical magazine Charlie Hebdo (a product of irreverent 1970s nihilism) received muted support from parts of the left after the terrorist attacks it was subjected to in January 2015.

“Issue” here should be understood as the most disaggregated level of questioning, where a position is reflected by support for or opposition to a specific proposition. Suppose that, on a general topic like nuclear energy, people oppose it when it involves older-generation reactors but support it when it concerns new-generation reactors. In that case, instead of a single question about being for or against nuclear energy, one would consider two distinct questions to map individuals’ positions in a multidimensional political space: for or against old-generation reactors, and for or against new-generation reactors.

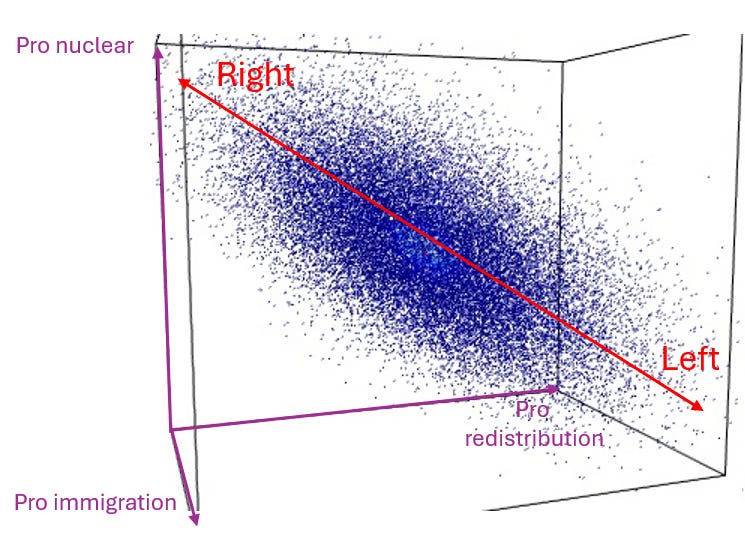

Consider, for instance, a hypothetical political space based on responses to just three issues: support or opposition to redistribution, nuclear energy, and lowering immigration. Given an individual’s answer to each of these questions on a scale from –10 (strongly opposed) to +10 (strongly in favour), that person can be located in a three-dimensional space. When a large number of individuals are placed in this space, they form a cloud of points. If answers are somewhat correlated (e.g. people relatively more in favour of redistribution also tend to be relatively more supportive of immigration), then the cloud will take on an oval shape. The line connecting the opposite poles of this oval shape, technically, the principal component, can be thought of as the natural dimension of political opposition that best summarises the main divide in the population.

The reason is that multidimensional spaces frequently lack a Condorcet winner — a position that would defeat all others in direct pairwise comparisons. As a consequence, multidimensional spaces are often filled with rock-paper-scissors–like cycles. For example, if you have three policies A, B, and C, you might find that a majority prefers A and B over C, another majority prefers B and C over A, and yet another prefers A and C over B.

This result arises when there is no Condorcet winner, that is, no candidate who would win in every pairwise contest against any other candidate. In a multidimensional space, a Condorcet winner corresponds to a combination of political positions across all dimensions that would defeat any alternative combination. For instance, if there are two dimensions (an economic dimension and a cultural dimension), there would need to be a position in that space that beats every other. As the number of political dimensions increases, it becomes harder to find a Condorcet winner, increasing the likelihood that no stable coalition exists, as every coalition contains a subset of players who could obtain higher payoffs by forming a different coalition.

The idea of these two political dimensions was promoted by Eysenk (1954), Nolan (1971) and Kitschelt (1994).

Here are original diagrams from Kitschelt (2003). Note that the vertical axis is reversed compared to the political compass, with authoritarian positions at the bottom.

Technical detail for the interested reader:

This conclusion is based on the use of Multiple Correspondence Analysis, which identifies the main dimensions that stretch the cloud of observations in a multidimensional space. In a multidimensional political space, the primary dimension stretching the cloud might correspond, for instance, to the left–right opposition (see footnote 4). In the space of cultural practices, education, and income, Bourdieu finds that the two most relevant dimensions for explaining social differences are, first, a dimension opposing those with high income and high education to those with less of both, and second, a dimension distinguishing those with relatively more education and less income from those with relatively more income and less education.

Having conducted this analysis, Bourdieu is then able to “place” votes for political parties in that space to observe how political allegiances tend to cluster in relation to these axes.

Here is the original graphic published in Distinction. The vertical axis distinguishes individuals with high levels of both economic capital (wealth) and cultural capital (education) from those with low levels of both. The horizontal axis contrasts those with relatively more cultural capital on the left and those with relatively more economic capital on the right.

While France differs in many ways from the US, Bourdieu’s findings are generally considered relevant to other Western countries. His statistical results showing how the education/income space structures social practices have been reproduced in the UK by Bennett et al. (2008). In the US, Lamont (1992) argued that Bourdieu’s analysis did not naturally extend to the American context, as people there were less likely to use differences in education and culture for social distinction. However, a more recent analysis by Currid-Halkett (2017) suggests that the role of education has grown as a marker of social distinction alongside income.

This is a great deep dive into the concept of left and right being multi dimensional axes of political orientation: authoritarian versus libertarian and economic leftism that seeks redistribution versus economic rightism that opposes it. I think maybe it should not be called libertarian but liberal. Libertarian implies a belief in minimal government but liberalism implies a government that does not impose on people but it doesn’t necessarily imply a minimal government. I’m definitely going to read that author who writes about the nature of shifting political alliances! Thanks for this great post! Also I think that writer is named Richard not Norman https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/McKelvey–Schofield_chaos_theorem

The description of the voting coalitions is about right, but the claim that conflict over income distribution has ceased to be a defining feature is wrong. The most extreme example is the Republican tax bill, but the same division is evident in Australia with the fights over the Stage 3 tax cuts and the taxation of super

One fact that has surprised many observers is that as high education high income voters have shifted to left parties, they have also shifted left on economic issues, while the reverse has happened on the right, particularly in the US.