Why elections have surprised us in recent years

On the instability of political coalitions

In his classic book, The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins made the following observation about the instability of human coalitions:

Pacts or conspiracies based on long-term best interests teeter constantly on the brink of collapse due to treachery from within. - Dawkins (1976)

This observation goes beyond the familiar instability of collusive agreements such as economic cartels. It encapsulates a deeper truth about the fragility of social coalitions. In this post, I discuss one illustration of this fragility: the recent shifts in political coalitions in Western democracies.

The evolution of the left-right coalitions

Is demography political destiny?

During the 2024 US Presidential campaign, Elon Musk claimed that if the Democrats were to win, it might be the last “real” election in America—a claim attributed to a mass influx of illegal immigrants who would eventually join the Democratic ranks.

While the suggestion of a deliberate plot to engineer US democracy is a stretch, Musk’s accusation is based on two facts. First, the Biden administration did oversee a substantial increase in illegal immigration at the Southern border. Second, voting statistics confirm that migrants are statistically more inclined to support the Democrats. Indeed, Musk’s assertion echoes a widely held view on the US left—that the growing proportion of Americans from ethnic minorities will eventually lead to the long-term dominance of the Democratic Party. This idea, sometimes labelled “demography is destiny,” is regularly discussed in the US and is explicitly stated in the 2016 book Brown Is the New White.

As Obama’s elections showed, the country’s demographic revolution over the past fifty years has given birth to a New American Majority. Progressive people of color now comprise 23 percent of all the eligible voters in America, and progressive Whites account for 28 percent of all eligible voters. Together, these constituencies make up 51 percent of the country’s citizen voting age population, and that majority is getting bigger every single day.

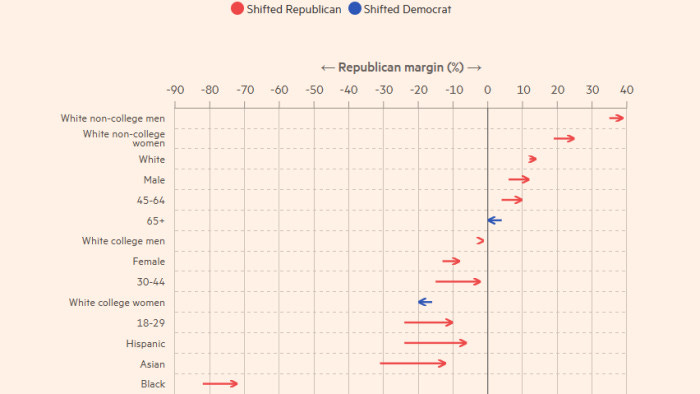

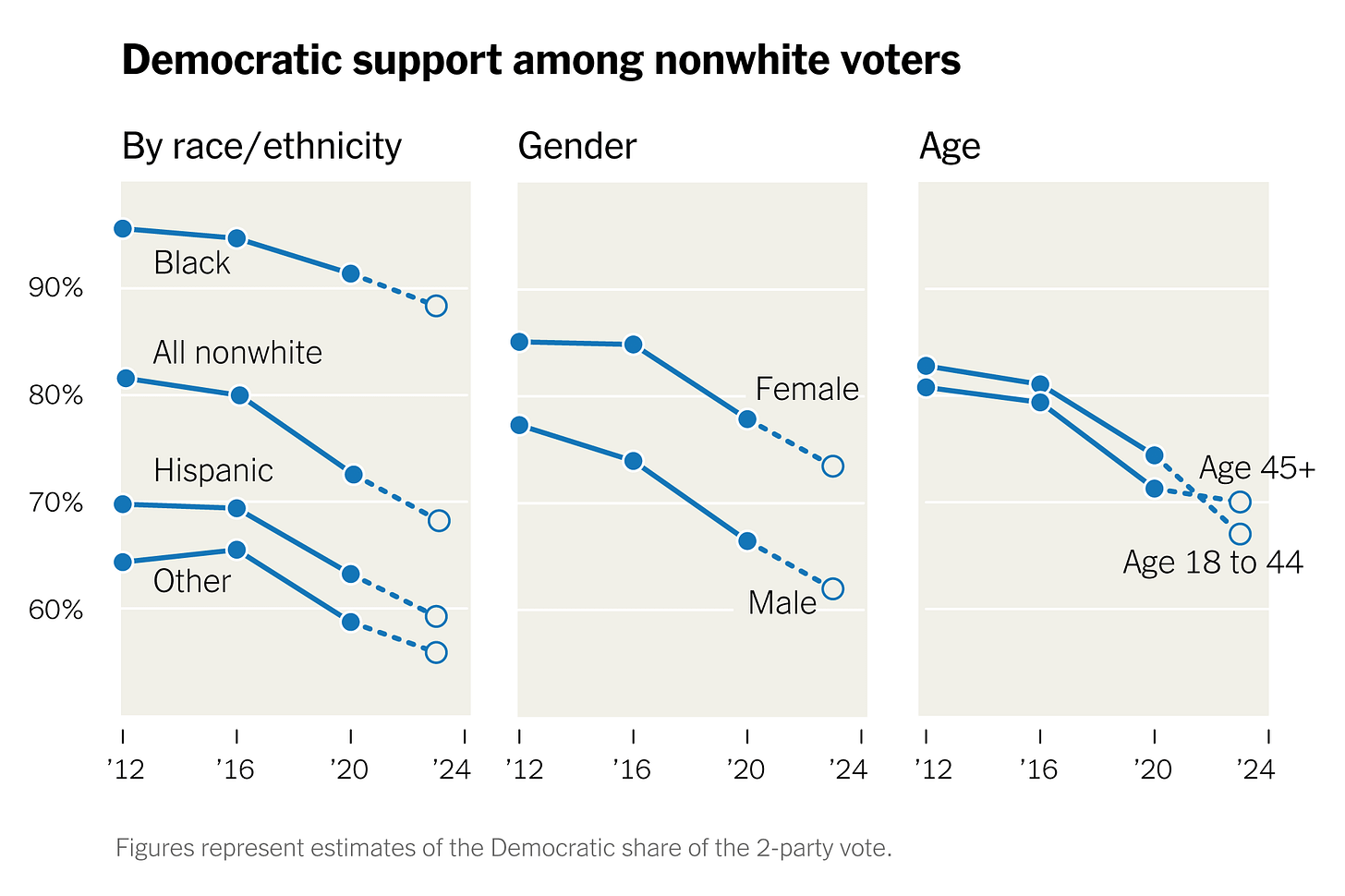

However, the presidential election dealt a severe blow to this perspective. It featured a substantial shift in minority votes toward Republican candidates, with Hispanic voters nearly splitting 50–50 between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris.

This outcome was not a freak accident; rather, it continued a trend observed in previous US presidential elections.

Thus, if the current trend continues, the notion of a long-term left-wing grip—secured by a demographic shift away from white America—appears unlikely. Both the predictions on the left and the worries of Elon Musk seem unwarranted.

The shift in socio-economic political coalitions

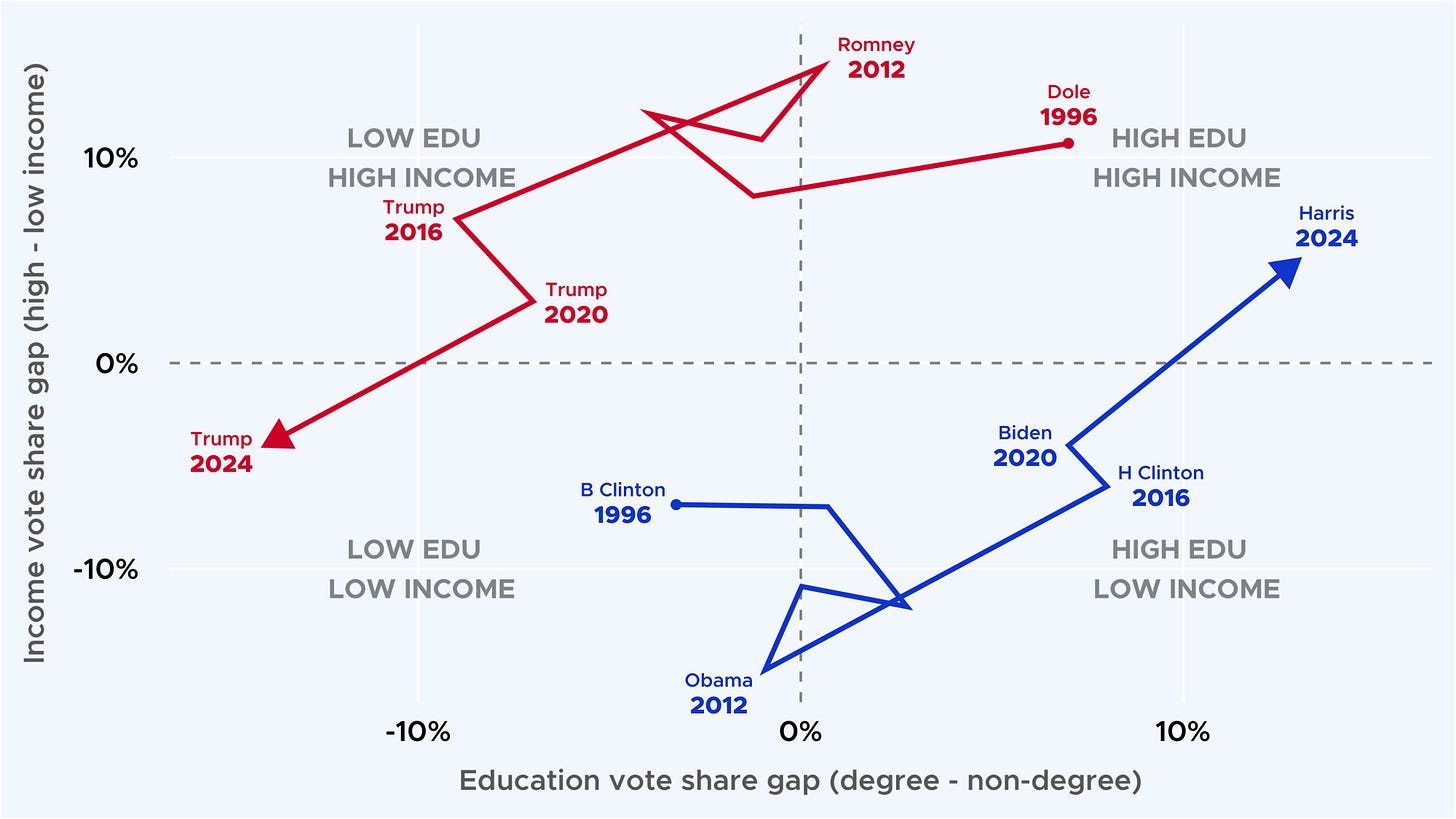

The other significant shift observed in the election was in the socio-economic composition of the Republican base. Over just 12 years, the Republican coalition shifted from being predominantly composed of high-education, high-income voters to a base of lower education and income. In that respect, the 2024 Trump coalition resembled the 1996 Bill Clinton coalition more than it did the coalition that supported Harris.1

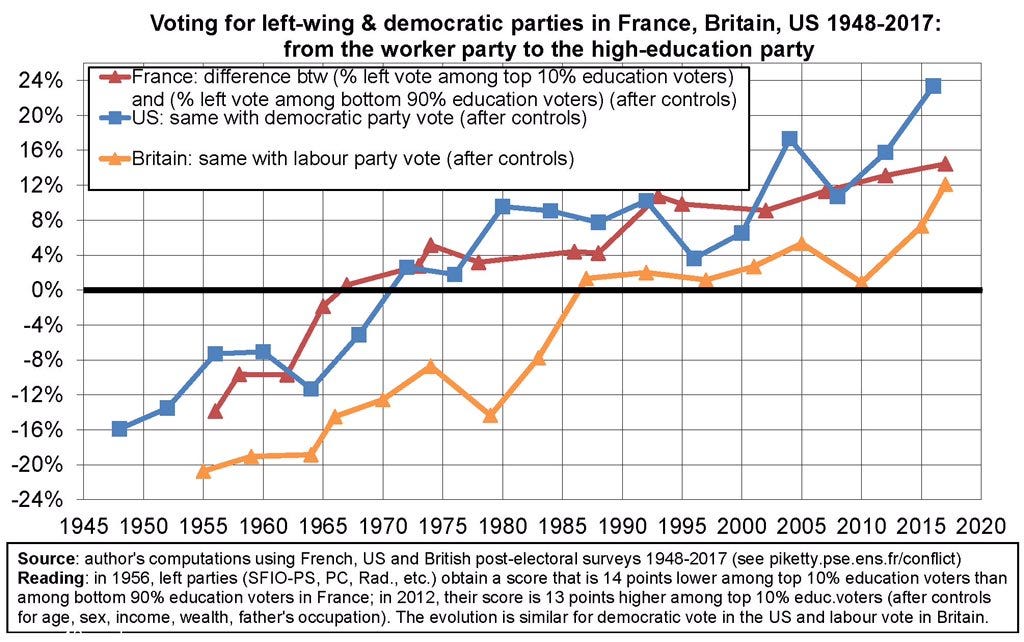

This evolution of electoral coalitions in the US is not unique. Economist Thomas Piketty has documented similar trends in various Western democracies. Over decades, voters and politicians in left-wing parties have become more educated, affluent, and urban. In a 2022 paper, Piketty and co-authors observe the rise of what he calls the “Brahmin left” (the elite and educated left) in 21 Western democracies (Gethin et al., 2022).

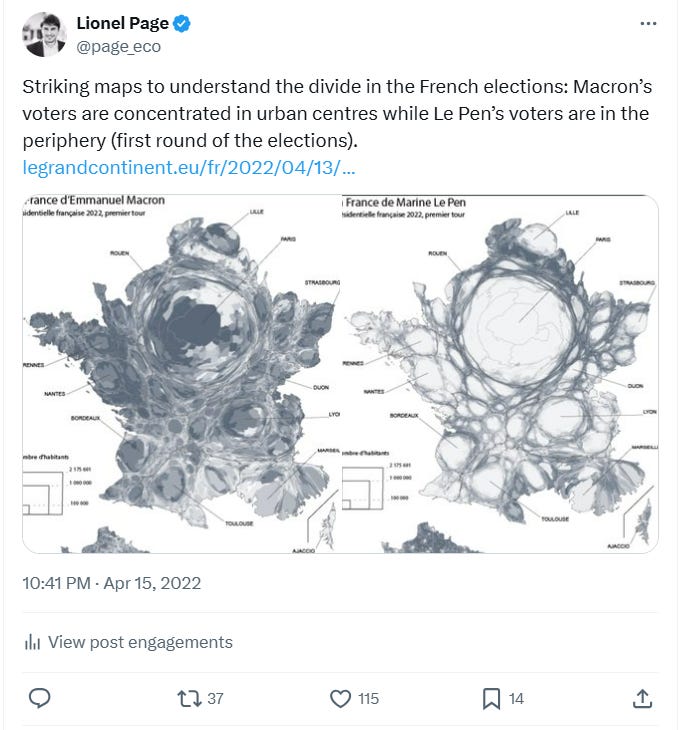

This socio-economic split has generated a new political geography. In several Western countries, we now observe urban centres filled with educated, high-income earners who tend to vote for left-wing parties, while peripheral areas with less economically advantaged citizens lean toward anti-establishment and often nationalist right-wing parties.2

The reasons behind these shifts are complex and cannot be solely attributed to national politics (e.g. “It is Obama’s fault”). They appear across diverse political systems, suggesting that broader structural forces are at work. This evolution intrigues political scientists and its precise causes are beyond the scope of this post.3 What is clear is that the nature of political coalitions on the left–right axis has undergone dramatic change over the past few decades.

A deep insight from coalitional game theory: coalitional stability can be hard

In my previous post, I presented a general framework for analysing situations in which coalitions form—any situation where individuals can choose to form groups and each group has a total payoff that depends on its members.

In the political context, game theorists look at a specific type of coalitional game: weighted voting games. In such games, players with different weights (for example, social groups of different sizes or political groups with different numbers of MPs in Parliament) aim to form a winning majority.4

The set of stable coalitions is often… empty

A central question in these games is how stable coalitions can be. Can a political coalition form and remain the same over time? To address this, Donald Gillies (1953) proposed examining the set of coalitions that would remain stable under renegotiation—that is, coalitions in which no subgroup of members has an incentive to break away and form or join a new alliance. He gave this set a somewhat cryptic name, “the core,” a concept now central to cooperative game theory.5

Looking for stable situations is kind of second nature for game theorists. If we want to explain the regularities of social interactions, it is useful to have strategic models that can predict that people will adopt regular patterns of behaviour. Game theorists are, for that reason, interested in the notion of equilibrium: a situation where no player has an interest to unilaterally deviate and change his or her behaviour. The notion of the core can be seen as similar in spirit to the notion of equilibrium but allowing for groups of players—instead of just one—to deviate together.

In 1950, John Nash had shown that every finite game has at least an equilibrium. Would it be the case that every coalitional game also has at least one coalition stable to deviations by groups of players? Gillies demonstrated that this is not the case. The core can be empty! Indeed, it is typically empty in weighted voting games.6

Example: the divide-the-dollar game

Consider a simple example of weighted voting games. Imagine that Alice, Bob, and Carol must agree on how to divide a dollar. They need a majority—any two agreeing on a division—for the decision to be implemented. For instance, they could decide to all agree to split the dollar equally: 1/3, 1/3, 1/3.

However, this “grand coalition” is unstable. Alice might suggest to Bob that they instead propose a division of 1/2 and 1/2 for themselves, excluding Carol. If Bob agrees, all seems well until Carol, facing the prospect of nothing, intervenes. She could tell Bob, “At the moment, you get 50% of the dollar under the deal with Alice. What if we arrange for 60% for you and 40% for me? We would both be better off.” Bob, tempted by a better payoff, might switch allegiance. Yet, before the new agreement is finalised, Alice—now set to receive nothing—could approach Carol with an even more attractive offer: “. In an instant, Bob is ousted, and a new cycle of negotiation begins.

This endless cycle of renegotiation demonstrates that no coalition in such a setting can be entirely stable if members are constantly tempted to defect for a better deal.

An illustration: Elite power and coalitional flexibility

The insights from the divide-the-dollar game can easily be applied to politics. It is not uncommon to hear claims that society is ruled by a cohesive elite—the “capitalists,” the “military-industrial complex,” and so on. Such views were popularised by works like C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite (1956) and G. William Domhoff's Who Rules America? (1967). Elite forums such as Davos or the Bilderberg Group are often cited as evidence of a top-down, elite-driven world order.7

In contrast to this view, political scientist Robert Dahl argued in his book Who Governs? (1961) that elites are most often divided by internal competition rather than united by a singular purpose. This view is supported by insights from game theory: We should not expect an elite coalition ruthlessly dominating the masses to be necessarily a stable coalition. Divisions can occur both within elites and within the masses.

The populist case. Consider the case where a powerful member of the elite leverages mass support to monopolise power at the expense of other elites.

This strategy is not new. In Ancient Rome, Caesar adopted such an approach against the traditional political elite that controlled the Senate. By introducing debt relief, granting land to veterans and poor citizens, and expanding Roman citizenship, Caesar mobilised popular support. In Plutarch’s words:

He had the people’s support; with it he would conquer everyone, and win the highest place of all.8

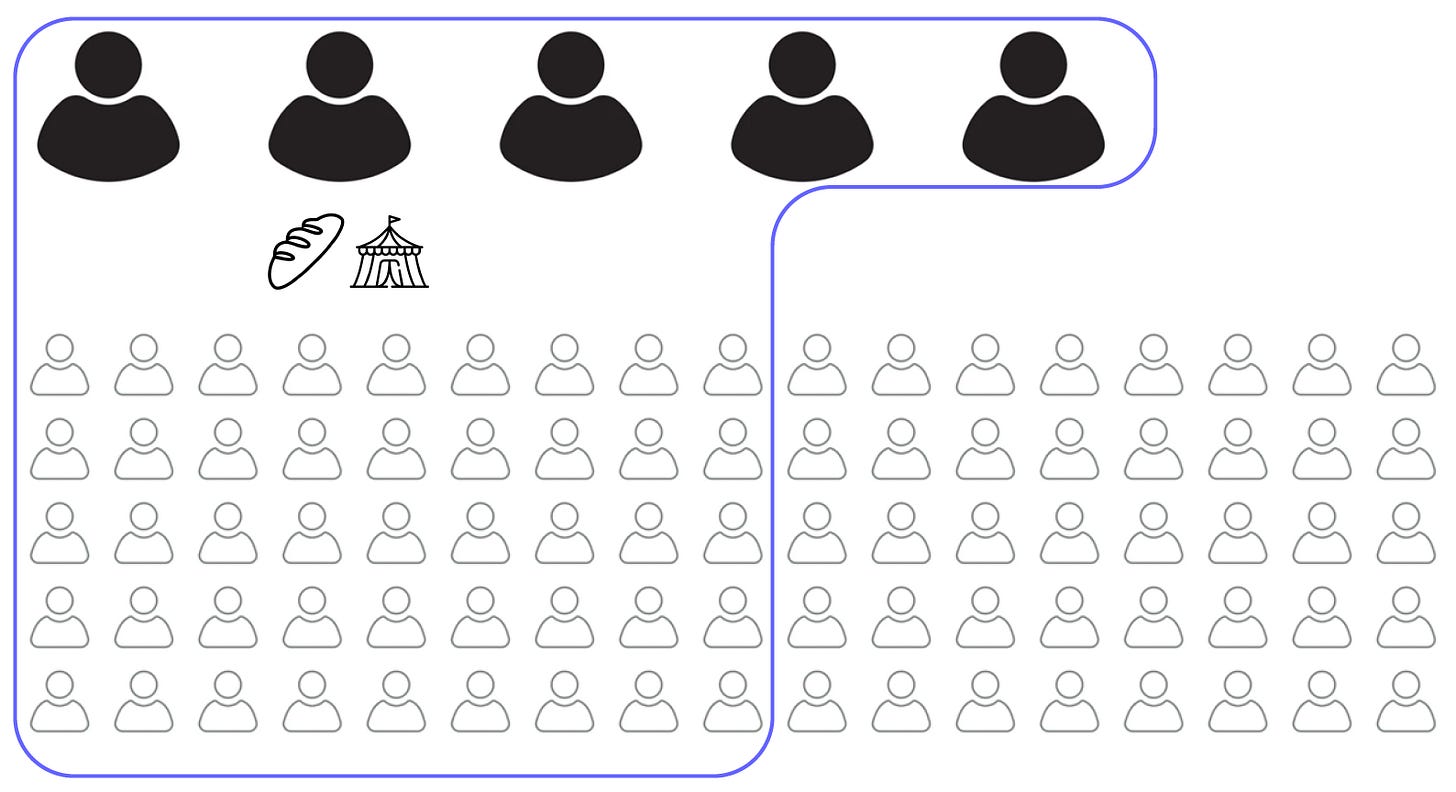

The buyout case. Another type of alliance between elites and the masses is when the elite improve the welfare of the masses to prevent revolt.

Juvenal’s recommendation to give bread and circuses to the Roman population illustrates this idea.

The buyout strategy can also serve to undercut a populist challenge. Plutarch recounts the actions of Cato, defending the Republic against Caesar:

He was particularly afraid that the poor might start a revolution: they were the spark that could set the populace alight, and all their hopes rested with Caesar. So Cato persuaded the senate to give the poor a monthly allowance of corn. This added 7,500,000 drachmas a year to the state’s expenditure, but it was clearly most effective in damping down the immense immediate danger. It also broke up and dispersed most of Caesar’s power. - Plutarch (110AD)

Two thousand years later, Bismarck explicitly acknowledged the buyout strategy when he introduced a social security system in Germany to thwart the rise of socialist ideas among the working class:

My idea was to bribe the working classes, or shall I say to win them over, to regard the state as a social institution existing for their sake and interested in their welfare.9

Notably, the buyout strategy need not rely solely on economic incentives. An elite may also adopt cultural stances that resonate with the masses. In his book Political Competition, John Roemer explains how an economic elite might receive the support of poorer voters by taking culturally conservative positions that are popular.10 This explains the seemingly paradoxical but often-seen alliance between culturally conservative and economically liberal political parties.

Then why do political coalitions seem stable?

Given the lack of stable coalitions in weighted voting games, it is striking that real-world political alliances often endure as long as they do. The answer likely lies in the repeated nature of political contests. Sustained cooperation likely persists due to the risk of punishment in the future, if a party betrays a coalition agreement. A party that betrays its coalition may find itself excluded from future alliances. Likewise, a party that shifts its positions too rapidly risks being branded as opportunistic and unreliable by voters. Reputation for keeping one’s word, being faithful to one’s ideas, and being loyal to one’s coalition partner would increase the chance of being part of a coalition. However, these constraints might not prevent gradual shifts in positions that lead a coalition to shift over time as we have observed in recent elections in Western countries.

What it means for democracy

Coalitional instability might paradoxically be good news

The fact that no coalition is likely stable in voting games can seem disappointing at first sight, but it is in fact likely a blessing for the democratic process. It means that any group has the potential to become part of a winning coalition. No segment of society is forever under the tyranny of a permanent majority, which in turn promotes widespread acceptance of democratic conflict resolution. If you lose today, you know that you might win tomorrow. Robert Dahl, known for his work on democracy, emphasised the importance of the instability of a majority for the democratic process to work.

The stronger the expectations among the members of a political minority that they will enter into tomorrow's majority, the more acceptable majority rule will be to them, the less they will feel a need for such special guarantees as a minority veto, and the more likely they are to see these as impediments to their own future prospects as participants in a majority government. - Dahl (1989)

The possibility for each social group to be part of a coalition also gives each of them bargaining power in the political process. Lloyd Shapley's work provides a key intuition that payoffs are divided among possible coalitional partners as a function of their bargaining power. The instability of majority coalitions means that every group can claim a slice of the pie generated by society.

Coalitional stability might impede a functional democratic state

On the other hand, when coalitions are formed along rigid cultural, ethnic, or religious lines, they tend to be less open to change. This rigidity can lead to long-term minority status for some groups, fostering persistent distrust in democratic institutions and resistance to the growth of state authority leading to limited state capacity—the ability to enforce laws, maintain order, implement policies, and deliver public services.11

The negative impact of social divisions on mutual trust and state capacity is well documented. Empirical studies have found that countries characterised by ethnic fragmentation tend to have lower public good provision (Easterly and Levine, 1997; Alesina et al., 1999). Such fragmentation may explain the weakness of state structures in countries like India (Dahl, 1998; Banerjee et al., 2005), Lebanon (Khatib and Gardiner, 2015),12 Bolivia and Ecuador (Eaton, 2007), and Kenya (Miguel and Gugerty, 2005).13

Political coalitions are not immutable. They can evolve when a group in the majority identifies a more advantageous opportunity on the opposition side. Any political party that takes a specific social group for granted is misguided.

Recent decades have shown that voters from lower social backgrounds are no longer irrevocably tied to left-wing parties. The idea of a fixed demographic destiny consigning minority voters almost exclusively to the left has also been undermined by recent electoral shifts. The possibility that conservative parties might broaden their appeal across ethnic lines can only be seen as a positive development for the health of liberal democracies. The very contestability of each group in coalition bargaining ensures that their interests and views are bound to be taken into account.

This is the second post in a series on coalitions. The first post introduced the game theory and psychology of coalitions. The next post will discuss the paradox of power.

Reference

Acemoglu, D. and Robinson, J.A., 2019. The Narrow Corridor: How Nations Struggle for Liberty. Penguin UK.

Alesina, A., Baqir, R. and Easterly, W., 1999. Public goods and ethnic divisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(4), pp.1243–1284.

Apprioual, A. (2016). Lebanon's Political Stalemate: The Failure of the Sectarian Regime. POMEAS Policy Brief, No. 11, February. Available at: https://ipc.sabanciuniv.edu/Content/Images/CKeditorImages/20200413-23041889.pdf

Banerjee, A., Iyer, L. and Somanathan, R., 2005. History, social divisions, and public goods in rural India. Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(2–3), pp.639–647.

Bondareva, O.N., 1963. Some applications of linear programming methods to the theory of cooperative games. Problemy Kibernetiki, 10, pp.119–139.

Codevilla, A.M., 2010. The Ruling Class: How They Corrupted America and What We Can Do About It. Beaufort Books.

Collier, P., 1913. Germany and the Germans from an American Point of View. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

Dahl, R.A., 1961. Who Governs? Yale University Press.

Dahl, R.A., 1989. Democracy and its Critics. Yale University Press.

Dahl, R.A., 1998. On Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Easterly, W. and Levine, R., 1997. Africa's growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, pp.1203–1250.

Eaton, K., 2007. Backlash in Bolivia: regional autonomy as a reaction against indigenous mobilization. Politics & Society, 35(1), pp.71–102.

Fukuyama, F., 2014. Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Gethin, A., Martínez-Toledano, C. and Piketty, T., 2022. Brahmin left versus merchant right: Changing political cleavages in 21 Western democracies, 1948–2020. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(1), pp.1–48.

Gilles, R.P., 2010. The Cooperative Game Theory of Networks and Hierarchies. Berlin: Springer.

Khatib, L. and Gardiner, M., 2015. Lebanon: Situation Report-Carnegie Middle East Center.

Kitschelt, H., 1994. The Transformation of European Social Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kitschelt, H., 2003. Diversification and reconfiguration of party systems in postindustrial democracies. Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Available at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/02608.pdf

Kotkin, J., 2020. The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. Encounter Books.

Lasch, C., 1994. The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy. W.W. Norton & Company.

McKelvey, R.D., 1976. Intransitivities in multidimensional voting models and some implications for agenda control. Journal of Economic Theory, 12(3), pp.472–482.

Miguel, E. and Gugerty, M.K., 2005. Ethnic diversity, social sanctions, and public goods in Kenya. Journal of Public Economics, 89(11–12), pp.2325–2368.

Piketty, T., 2003. Attitudes vis-à-vis des inégalités en France: Existerait-il un consensus? Comprendre, 4, pp.209–241.

Plutarch, c. 110 AD (2011). Caesar. Translated with an introduction and commentary by Christopher Pelling. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roemer, J.E., 2009. Political Competition: Theory and Applications. Harvard University Press.

Shapley, L.S., 1967. On balanced sets and cores. Naval Research Logistics Quarterly, 14(4), pp.453–460.

Singh, P. and vom Hau, M., 2015. Ethnicity, state capacity, and development: Reconsidering causal connections. In: The Politics of Inclusive Development: Interrogating the Evidence, pp.231–258.

As Musa al-Gharbi puts in an analysis of the US electoral results, this coalitional shift—as well as the shift in the vote of ethnic minorities—was part of a graveyard of electoral narratives.

In his influential 2017 book The Road to Somewhere, David Goodhart characterised these new political coalitions as the opposition of the “anywheres” (the educated elite favouring openness) and the “somewheres” (economically less advantaged people whose lives are grounded in a specific place).

I might discuss the possible causes behind this evolution in a later post.

In a weighted voting game, players have different weights that reflect their importance when they join a coalition (for example, the number of votes a group’s representative holds). For a coalition to win, the sum of its weights must exceed a quota (commonly 50%, though sometimes higher, as in a 75% supermajority).

To be precise, the core is the set of stable coalition agreements—payoff allocations that no coalition has an incentive to reject (Gilles, 2010). A given coalition may sustain several stable agreements.

It is empty in weighted voting games if there is no player with a veto and if players can switch from one coalition to another one. In other words, the core is empty—there is no stable coalition—in weighted voting games that have the characteristics of typical bargaining situations to form a majority in a democracy.

The general condition for a core to be empty was established independently by Olga Bondareva (1963) and Lloyd Shapley (1967). For readers interested in the topic, see Gilles (2010).

In the 20th century, criticisms of dominant elites primarily emanated from the left side of politics and targeted the economic elites. In recent years, criticisms have also appeared against the educated and liberal elites that prevail in many institutions (e.g., Lasch 1994, Codevilla 2010, Kotkin 2020). The points made in this section apply equally to these elites.

As Caesar’s power grew, he won a high office in a close election. This worried the political elite.

The senate and the best people were terrified. He would encourage the ordinary people to be reckless and aggressive. - Plutarch (110AD)

Illustrating this, Plutarch recounts that during a Senate debate in which Caesar was accused of complicity in the Catiline affair, a large crowd of his supporters gathered outside.

When Caesar had gone into the senate and was defending himself against the insinuations of complicity. His opponents heckled him loudly, and the senate-sitting was lasting longer than normal: so the people marched noisily on the senate house and surrounded it, shouting for Caesar and insisting that he should be allowed to leave. - Plutarch (110AD)

This quote, which I found via Ruxandra Teslo, is cited by Collier (1913).

Roemer, an analytical Marxist—that is, a scholar who uses rigorous tools from rational choice theory, game theory, and empirical social science to provide a foundation for Marxist ideas—interprets this type of buyout strategy as a disingenuous ploy.

We may finally reflect upon a view, which has often been held in Left circles, that the Right deliberately “creates” a certain noneconomic issue—or tries to increase the salience of some such issue for voters—as a means of pulling working-class voters away from Left parties, thereby driving economic policies to the right. In this view, the Right party pretends to care about, say, the “religious” issue, while in fact being interested only in lowering tax rates (or rolling back nationalization and so on). Right may implement this masquerade by attracting political candidates who do, indeed, feel strongly on the “religious” issue.

But in fact, this interpretation of motives is not necessary. Such an alliance could also just happen if economic elites really harbour conservative views on cultural issues.

In his book Political Order and Political Decay, Fukuyama stressed the importance of trust in institutions for a country to be able to build state capacity. When the population does not trust its government, it resists delegating the required power upward of fear that it might not be in their best interest.

Putting loyalty to the state ahead of loyalty to family, region, or tribe requires a broad radius of trust and social capital. Britain and the United States are traditionally societies with good endowments of both. - Fukuyama (2014)

The same argument was made by Acemoglu (Nobel Prize winner in 2024) and Robinson, in their book The Narrow Corridor (2019). Like Fukuyama, they emphasised that a balance between state and civil society is required for institutions to function properly. A state that is too weak cannot fulfil its role, while an overly strong state is likely to support extractive institutions that exploit the population.

Lebanon provides a dramatic example. The country’s population is roughly divided among Christians, Sunni Muslims, and Shia Muslims. Although formally a democracy, its political system follows a power-sharing model in which government positions and institutional representation are allocated by religious group rather than determined by electoral majorities. This arrangement was designed to prevent any single group from dominating, but it also limits governance flexibility and frequently leads to political deadlock. As a result, the state has been described as “weak by design” (Khatib and Gardiner, 2015), with limited capacity to implement decisions independently of entrenched political leaders.

Lebanese political institutions are plagued by corruption, gridlock, and intergroup tensions, leading to severe failures in state capacity. The state’s inability to enforce laws, maintain order, implement policies, and deliver public services is evident in daily life—power cuts lasting between 3 and 12 hours, unpredictable water shortages, and uncollected garbage piling up in Beirut’s streets for months (Apprioual, 2016). The most catastrophic consequence of this institutional failure was the 2020 Beirut explosion. Due to corruption and negligence, 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate had been stored unsafely at Beirut’s port since 2013. Several government agencies were aware of the danger but failed to act, ultimately leading to one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history.

For a rich discussion of the effect of ethnic fragmentation on public good provision, see Singh and Hau (2015).

I am not a serious researcher like you, but I actually wasn’t surprised. Maybe I am an idiot savant, lol

"Over decades, voters and politicians in left-wing parties have become more educated, affluent, and urban. In a 2022 paper, Piketty and co-authors observe the rise of what he calls the “Brahmin left” (the elite and educated left) in 21 Western democracies (Gethin et al., 2022)."

This is why today's Left spend such energy debating burning topics such as the rights of sexual minorities so oppressed that they have not even been discovered yet.

At the same time, the PMC take it as granted that as the smarter, better educated, more virtuous, tasteful and enlightened people, they are naturally entitled to the lion's share of The Goodies.