There are no moral laws out there

A criticism of moral realism

In this series of posts, I tackle the big question of fairness and morality: what they are and where our moral sense comes from. In my last post, I argued that religion is not the cause of human concerns for morality. Here, I criticise moral realism, the appealing idea that there are objective moral truths.

This Substack is not for the epistemically faint-hearted (i.e. not for those afraid of what the truth might be), so let’s get something out of the way. I believe it does not make sense to talk of morality as being objective, in the sense that there would be absolute moral truths.

The reason is that, if you take a naturalistic approach without skyhooks, I do not see in what sense there could be moral truths external to us. Where would they come from? How would we access them? I share the incredulity Binmore expresses here:

Diogenes remarked that he had seen Plato’s cups and table, but had yet to see his cupness and tableness. I feel much the same about the Platonism of traditional theories of the Good and the Right. — Binmore (1998)1

The philosopher most well-known for rejecting the absolute reality of morality is Nietzsche. In Beyond Good and Evil, he stated:

There are no moral phenomena, only a moral interpretation of phenomena.

For him, moral statements do not reflect some objective moral truths. They are social and historical narratives, human inventions. But wait, isn’t this paving the way to moral relativism, and the justification of any horrible behaviour we can think of? Here, I discuss why there is no reason to believe that there are absolute moral truths. In the next post, I’ll discuss why this conclusion does not lead to the justification of asocial behaviour.

Preferences over ice cream and Nazis

One specific aspect of morality is that we tend to experience moral norms as objective and externally imposed, rather than as mere personal preferences. Philosopher Kyle Stanford illustrates this with the contrast between saying “I like chocolate ice cream” and “The Nazis were bad.” The first is clearly a matter of taste, but the second feels different, something we take to be true regardless of anyone’s opinions.

Humans experience the demands of morality as somehow imposed on us externally: we do not simply enjoy or prefer to act in ways that satisfy the demands of morality; we see ourselves as obligated to do so regardless of our subjective preferences and desires, and we regard such demands as imposing unconditional obligations not only on ourselves, but also on any and all agents whatsoever, regardless of their preferences and desires. — Stanford (2018)2

The notion that moral injunctions have some objective nature is associated with moral realism, the idea that moral rules are real laws, in the same sense as the laws of physics.3

The philosophers’ view

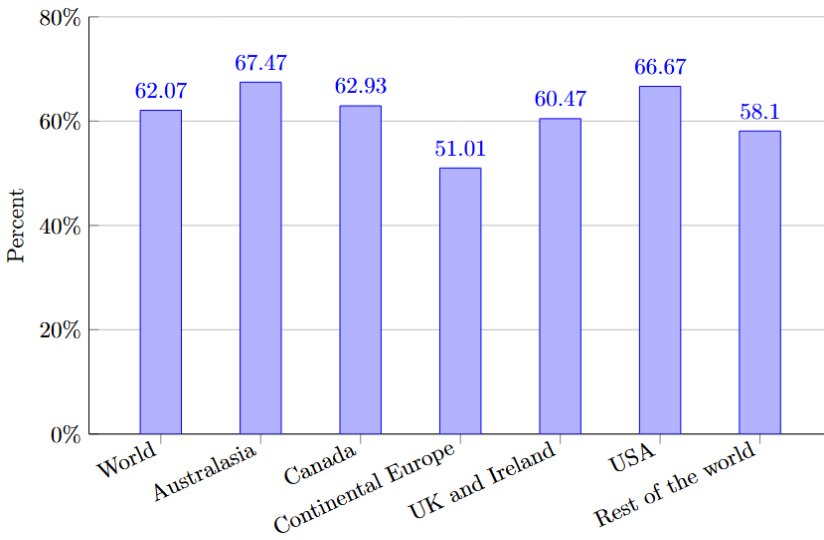

Modern philosophy has become mostly secular, but it is striking that the majority of philosophers seem to continue to support the view that there are absolute truths, independently of the question of the existence of a God. A recent 2020 PhilPapers Survey indicated a clear majority supporting moral realism among philosophers across the world.

On Substack, philosophers like Peter Singer, Michael Huemer, Eric Schwitzgebel, Richard Y Chappell, Amos Wollen, Bentham's Bulldog, are in favour of moral realism while Matt Lutz, Lance S. Bush, and Philosophy bear are opposed to it.

The argument for moral realism

Moral realists argue that we can build a theory of morality. There are many different justifications for moral realism, but they often share similar features, such as the observations that we have strong moral feelings and experience them as objective, which might vindicate looking for the objective reasons behind these feelings.

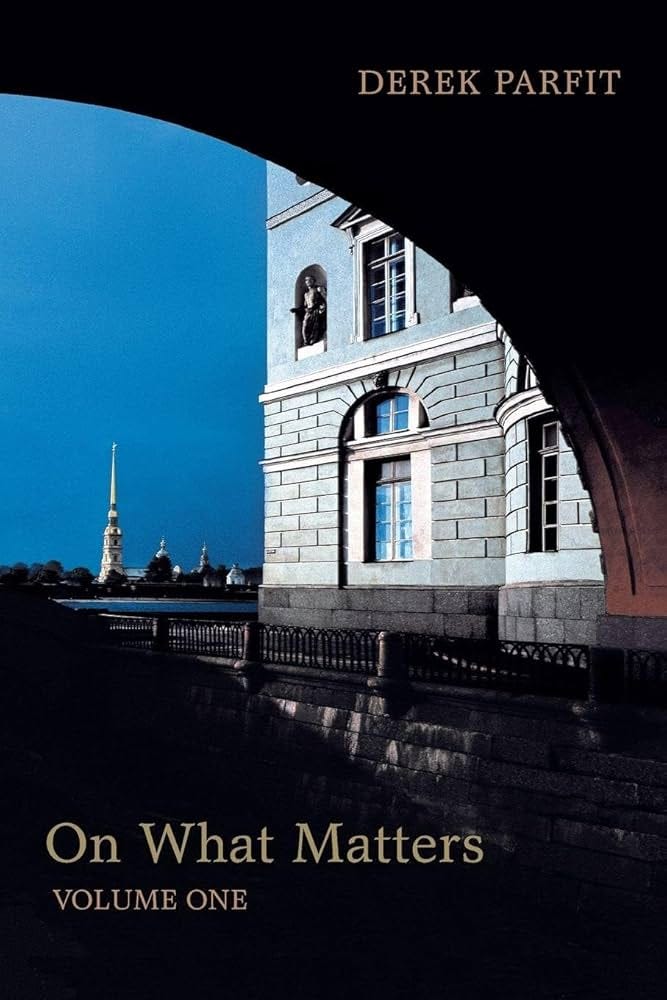

To engage seriously with moral realism, I’ll focus on the arguments of two influential thinkers: Derek Parfit, a leading moral philosopher, and Sam Harris, a well-known public intellectual with a wide popular impact.4

Derek Parfit’s non-naturalist moral realism

Derek Parfit is commonly seen as one of the most important moral philosophers of recent times, if not the most important. His views have had a major influence in academic circles and beyond. It therefore makes sense to turn to him when looking for one of the best possible advocates of moral realism. He defends the objectivity of morality in his book On What Matters (2011).

At the heart of Parfit’s view is the claim that, in addition to “internal” reasons we have for action (those that come from our personal desires), there are objective “external” reasons to act that apply to us whether or not we are motivated by them. Imagine a person who enjoys causing pain and feels no sympathy or guilt. Given his present desires, he would be happier if he tortured a defenceless prisoner. On a purely “internal reasons” view, this person has no reason not to torture; in fact, he has an internal reason to torture, because it satisfies his strongest desires. Parfit wants to say that, even if this person has no such internal motives, he still has a powerful reason not to torture. That reason does not depend on what he now wants; it is grounded in the suffering he would inflict. This is what Parfit means by an external reason, and he argues that such external reasons are real.

We all have reasons to regret anyone’s suffering, and to prevent or relieve this person’s suffering if we can, whoever this person may be, and whatever this person’s relation to us. We have such reasons to prevent or to regret the suffering of any sentient or conscious being. — Parfit (2011)

If there are external reasons, can we systematise them and build a moral theory that makes sense of them? Parfit thinks so, and he claims that, in the process, this theory unifies the main moral approaches, Kantianism, rule consequentialism, and contractualism, which, on his view, have been climbing the same mountain from different sides.5

This systematisation relies on making sure we uncover a moral theory that is internally coherent: it does not lead to contradictory injunctions. It also relies on checking that its conclusions align with our reasoned moral intuitions (those moral intuitions that withstand some scrutiny) about what the right thing to do is.

We might question what the epistemic status of such a systematisation is. Let us say Parfit is successful at building such a theory. What does that mean?

From a naturalistic point of view, there are basically two ways in which a theory can earn its keep. First, it should be logically coherent. Second, it should be answerable to experience in some way. Hume makes this point bluntly:

If we take in our hand any volume; of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion. — Hume

Parfit claims that his reasoning does not fit within this dichotomy, that it is possible to find irreducibly normative truths by rational reflection. In fact, I think he is in practice only doing a variation on it. To start with, he clearly aims to produce a consistent theory. That is central to his project. Then, how does he “test” whether this theory is acceptable? He says that he reasons with cases and principles. But in practice, on what grounds does a case lead him to accept or reject a conclusion? It is whether the injunction to act in a certain way in that case fits with our considered moral intuitions.6

In other words, Parfit uses moral intuitions as the raw material against which principles are tested, using clever thought experiments that set up unusual situations as stress tests for the general application of those principles. From a naturalist point of view, what he actually does is to organise our moral intuitions into a coherent system, rather than to open an independent window onto a further layer of moral reality.

A problem with this approach is that it gives a lot of weight to our moral intuitions as the primary substrate on which to build a theory. The fact that we have intuitions is obvious, but why should we treat our intuitions as pointing to some moral truth “out there” to be discovered?7

One reason given by Michael Huemer, who also defends moral realism, is that

It is reasonable to assume that things are as they appear, in the absence of grounds for doubting this. — Huemer8

Applied to morality, the idea is: moral truths appear to us to be objective, and unless we have strong reasons to distrust this appearance, we should take it at face value. Our intuitions about right and wrong are then treated as evidence for objective moral facts.

With all due respect to Huemer, this is a weak argument once we take seriously what we know about how our moral psychology evolved. We have very good independent explanations of why we have moral intuitions, without positing a realm of moral truths “out there”. Our moral sense appears to be an evolved tool for navigating social life: coordinating cooperation, managing conflicts of interest, punishing betrayal, and so on. Seen in that light, there is no particular reason to expect our intuitions to track some separate, non-natural moral reality. We should expect them instead to track what tends to work well for creatures like us in the kinds of social games we actually play.

Put differently: even if you can build a neat and coherent theory that organises these intuitions, that does not by itself show that the theory describes objective moral facts. It may simply be a good higher-level description of the strategies that help us do well in social interaction. If our shared moral intuitions are there to guide us towards sensible behaviour in repeated social interactions, they will need to be broadly compatible with equilibrium strategies of social games: strategies that it is in our interest to follow when others follow them too.

For instance, to the extent that it is good to cooperate with people who are willing to cooperate with us, and not to cooperate with people who just want to take advantage of us, we should have clear moral intuitions about reciprocity.

In pure epistemic terms, it is not clear why the enterprise Parfit undertakes would lead to objective moral truths that are “mind-independent”, as described by moral realists. This criticism was advanced precisely by philosopher Sharon Street:

The challenge for realist theories of value is to explain the relation between these evolutionary influences on our evaluative attitudes, on the one hand, and the independent evaluative truths that realism posits, on the other. Realism, I argue, can give no satisfactory account of this relation. — Street (2006)

Even if there were objective moral truths “out there”, there would be no reason to expect our moral intuitions to be special windows onto them, since these intuitions are shaped by evolution, which is a blind process with no reason to drive our cognition towards intangible moral truths. Instead, it shapes our cognition to help us be successful in the sense of surviving and having surviving offspring.9

Sam Harris’ naturalist moral realism

Sam Harris is a neuroscientist and public intellectual, with several New York Times best-selling books. He hosts the podcast Making Sense, which has a large international audience. Harris developed his perspective on morality in his book The Moral Landscape (2010).

I chose to discuss Harris’ views because many readers are likely familiar with them, and also because his starting point is naturalistic, like the one I adopt in this Substack. Harris wants to ground morality in facts about conscious creatures and their experiences, not in a religious or metaphysical realm. This makes it easier to engage with his ideas and to identify where disagreements lie.

Harris’ starting point is that we are evolved beings with nervous systems that generate conscious experiences of pain and pleasure. From this, he says that some types of experiences are better than others.

He asks us to imagine the “worst possible misery for everyone”: a world in which every conscious being suffers as much as possible, for as long as possible, with no compensating benefits. Opposed to that, we can imagine much better possible worlds. Harris then asks whether we are prepared not to call the first world “bad” and the others “better”. If we are, we have already accepted that there are objective moral facts: some states of the world really are better than others, because they contain more well-being.

There is an obvious question though: as much as we feel that the first world is awful, why should we call it bad in an absolutely-objectively-true way, rather than in a we-really-don’t-like-it way? Harris anticipates this question:

But you haven’t said why the well-being of conscious beings ought to matter to us. If someone wants to torture all conscious beings to the point of madness, what is to say that he isn’t just as ‘moral’ as you are?

His answer has two parts. First, he claims that consciousness is “the only intelligible domain of value”:

I think we can know, through reason alone, that consciousness is the only intelligible domain of value. What is the alternative? I invite you to try to think of a source of value that has absolutely nothing to do with the (actual or potential) experience of conscious beings.

Frankly, I do not follow. With his question “what is the alternative?”, he simply introduces the assumption that there must be some “value” in the world. This is a skyhook. If you assume there needs to be such an objective value, you have pretty much provided a justification for a normative theory out of thin air.10 But what tells us that such an objective value exists? Isn’t that the first question to answer?11

Also, Harris says that “through reason alone” we can know that consciousness is the only domain of value. But, actually, he does not show this using reason. He is really only saying: “come on, you know deep down it is true”.

So really, it is a call to our intuition, and Harris joins Parfit (and many other moral realists) using our intuitions as a primary source of evidence. Having argued for such a value, it is then easy to claim that there are objective rights and wrongs.

Once we admit that the extremes of absolute misery and absolute flourishing—whatever these states amount to for each particular being in the end—are different and dependent on facts about the universe, then we have admitted that there are right and wrong answers to questions of morality.

Why should we agree with his line of argument? Because it is obvious, and, if we don’t, Harris suggests we are a kind of psychopath:

Anyone who doesn’t see that the Good Life is preferable to the Bad Life is unlikely to have anything to contribute to a discussion about human well-being. Must we really argue that beneficence, trust, creativity, etc., enjoyed in the context of a prosperous civil society are better than the horrors of civil war endured in a steaming jungle filled with aggressive insects carrying dangerous pathogens? I don’t think so. (emphasis mine)

The key here is what sense is given to better. Obviously, pretty much everybody would prefer to live in a prosperous civil society rather than in a civil-war-ridden society. But that does not mean that there is an objective value out there saying so. Indeed, the whole exercise should be to prove it, not say it is self-evident.12 Saying so is relying on our intuitions shaped by evolution.

So, Harris is a naturalist who smuggles an ought out of thin air on the ground that it is obvious if we think about it. The problem is that an immaterial ought is anything but obvious. Starting from a naturalist point of view has the merit of grounding the theory in well-known facts about human psychology, but it also makes the leap of faith to a normative standpoint easier to spot in its arbitrariness.

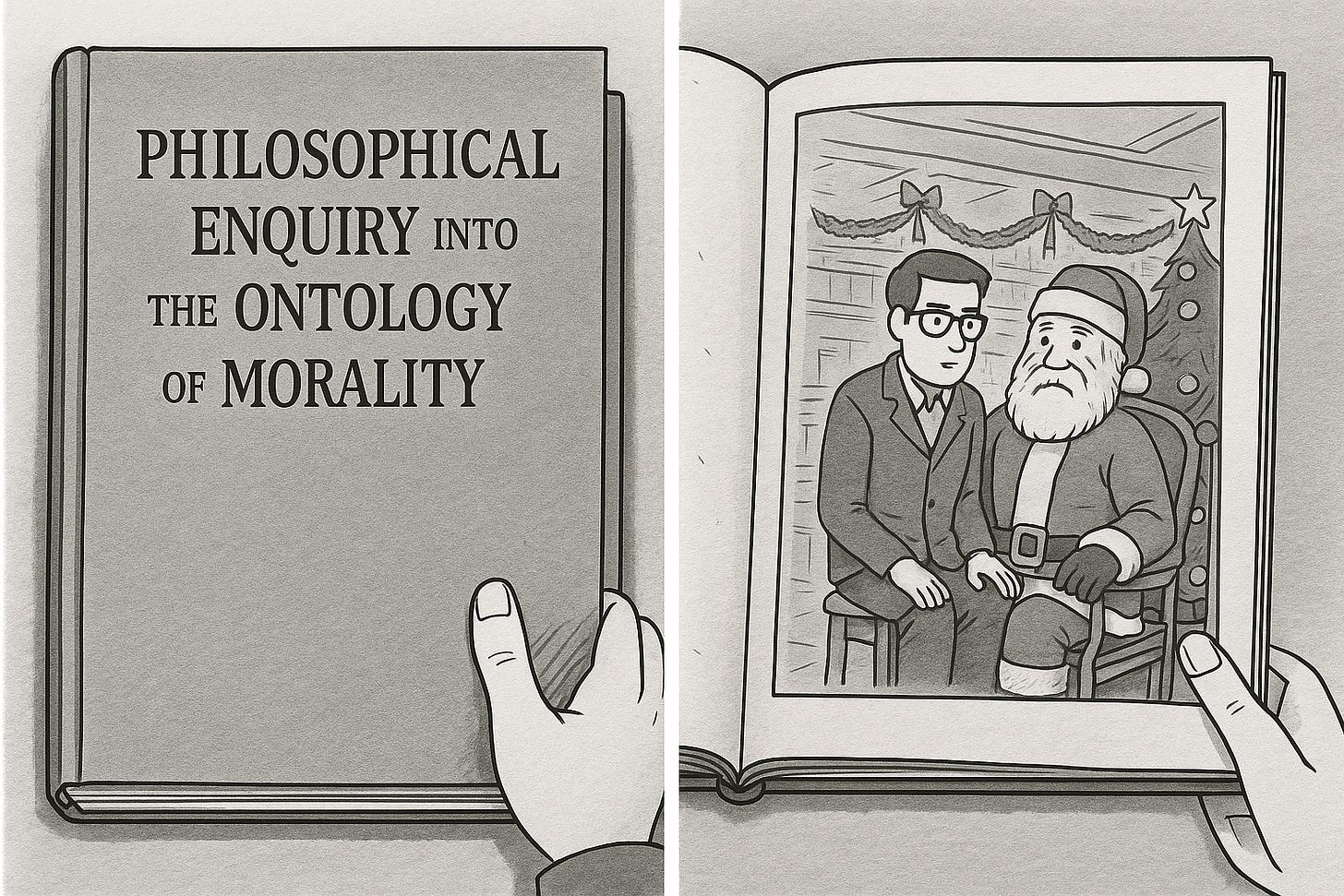

The motivation: appeal to consequences

Reflecting on his achievement, Parfit stated:

My life is my work. I believe I have found some good reasons for believing that values aren’t just subjective and that some things really do matter. If my arguments don’t succeed, my life has been wasted. — Edmonds (2021)

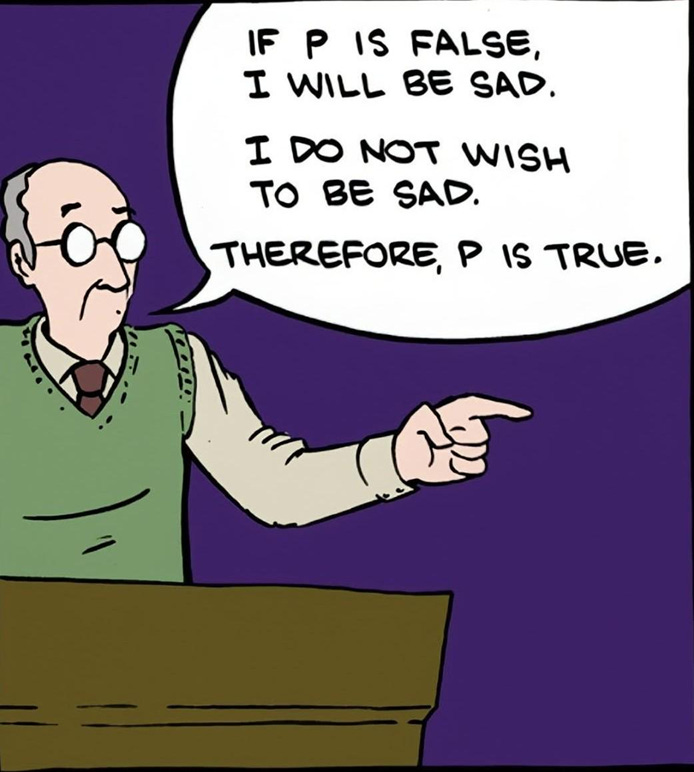

This existential motivation should, if anything, make us doubt Parfit’s intellectual impartiality. In a previous post, I described how the desire to believe something is true because we prefer it to be true, what I call the Santa Claus fallacy, often underlies technical arguments about morality.13

When looking at the motivations of moral realists, they often openly express a strong preference for the existence of moral truths, to the point of fitting the Santa Claus fallacy.14

Consider, for instance, David Enoch in Taking Morality Seriously:

In particular, under non-objectivist metaethical assumptions […] it would be morally impermissible to stand one’s moral ground in any number of conflicts or disagreements where it does seem permissible (perhaps even required) to stand one’s moral ground.15

In other words: if we want to be able to say that something is morally wrong, we need to believe there are objective moral truths.

Another moral realist, Russ Shafer-Landau, writes in Moral Realism: A Defence:

[if modesty, liberality, and tolerance were human constructs], then the illiberal and the intolerant, who have constructed things differently, would be making no error. — Shafer-Landau

In other words: if we want to be able to say that the illiberal and intolerant are morally wrong, we need to believe there are objective moral truths.

Huemer says in Ethical Intuitionism:

Lastly, moral anti-realism undermines our sense of meaning in life, and this brings me to one of the reasons why I find anti-realism unbelievable. I think anti-realism really boils down to the view that nothing matters. […] Life has no meaning, because “meaning” is one of those ‘spooky’, non-natural properties that anti-realists do not believe in.16 — Huemer

In other words: if we want our lives to have meaning, we need to believe that there are objective moral truths.

Turning back to the two thinkers I discussed earlier, Parfit wrote in On What Matters:

On subjective theories, nothing matters. We should reject the arguments for this bleak view.

And Harris wrote in The Moral Landscape:

Few people seem to recognize the dangers posed by thinking that there are no true answers to moral questions.

These appeals to consequences are flawed arguments. Whether I prefer something to be true or not should not influence my belief in it being true. I might have a very strong preference for Santa Claus to be real; it won't make it in the least more real. Similarly, the fact that I would very much like moral rules to be objective because of the judgements they would allow me to make is irrelevant to assessing whether these rules exist objectively.17 That such brilliant minds resort to such a flawed type of argument is testimony to the fact that our reason is a tool selected for us to convince ourselves and others, not primarily to find the truth.

In the end, the search for a justification for an objective theory of moral truth might be seen as an attempt to retain, within a secular framework, the type of absolute moral mindset that Judeo-Christian traditions had until now provided. This criticism was explicitly made by Sartre

Towards 1880, when the French professors endeavoured to formulate a secular morality, they said something like this: God is a useless and costly hypothesis, so we will do without it. However, if we are to have morality, a society and a law-abiding world, it is essential that certain values should be taken seriously; they must have an a priori existence ascribed to them. It must be considered obligatory a priori to be honest, not to lie, not to beat one’s wife, to bring up children and so forth; so we are going to do a little work on this subject, which will enable us to show that these values exist all the same, inscribed in an intelligible heaven although, of course, there is no God. […] nothing will be changed if God does not exist; we shall rediscover the same norms of honesty, progress and humanity, and we shall have disposed of God as an out-of-date hypothesis which will die away quietly of itself. — Sartre (1946)

William James suggested that philosophers often fall into two temperamental camps: the tender-minded, who are drawn to idealistic, and often more comforting, views, and the tough-minded, who insist on sticking to experience, facts, and logic, even when the resulting conclusions are not especially appealing.

This Substack definitely stands on the tough-minded side. There is no point in trying to argue that Santa exists just because we would like it to be the case. If we agree there is a reality out there, it does not depend on what we would like it to be. Understanding it as it is requires us to follow where logic and facts guide us. Furthermore, given the design of human reason—filled with reasoning biases that conveniently land us on our preferred conclusions—we should lean towards being suspicious of, rather than drawn to, our own preferences. In the domain of morality, this means that while we may find the idea of absolute moral truths appealing, we should be particularly vigilant about the reasons we accept in support of this view. The view I present in this post is that, when we do so, there are no good reasons to believe that it makes sense to talk of an objective moral reality out there.18

This conclusion leads to a natural question. Does the rejection of moral realism imply a radical relativism that takes the form of subjectivism (moral judgements are nothing more than personal preferences)? Does it mean that anything goes and that we have to agree that things like torture, slavery, and genocide are fine?

The answer here is negative. If morality is understood as being about social rules of cooperation, moral judgments are not just meaningless drivel. In that sense, the naturalistic perspective I develop here is different from the conclusions Nietzsche draws about morality. Discussing this, Binmore states:

[…] the classic error that Nietzsche makes on behalf of all the other thinkers who contrive to muddle the distinction between relativism and subjectivism is to confuse moral values and personal tastes. Morality evolved to regulate interactive human behavior. All the members of a particular society need to be playing the same morality game for its rules to serve any purpose. What would be the point of morality if it differed not only from one society to another, but also from one individual to another? — Binmore (1998, emphasis in the original)

A natural question is: what exactly is morality in this naturalist perspective? This will be the topic of my next post.

References

Binmore, KG (1998) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 2: Just Playing. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Bourget, D & Chalmers, DJ (2023) ‘Philosophers on Philosophy: The 2020 PhilPapers Survey’, Philosophers’ Imprint, 23(11).

Edmonds, D (2023) Parfit: A Philosopher and His Mission to Save Morality. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Enoch, D (2011) Taking Morality Seriously: A Defence of Robust Realism. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Golub, C (2021) ‘Is there a Good Moral Argument against Moral Realism?’, Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 24(1), pp. 151–164.

Harris, S (2010) The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values. Free Press, New York.

Huemer, M (2005) Ethical Intuitionism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Hume, D (1748) Philosophical Essays Concerning Human Understanding. A. Millar, London.

Hume, D (1755) ‘Of Suicide’, in EF Miller (ed.) Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary. Liberty Fund, Indianapolis.

James, W (1907) Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking. Longmans, Green & Co., New York.

Mackie, J.L. (1977) Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Nietzsche, F (1886) Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. C. G. Naumann, Leipzig.

Parfit, D (2011) On What Matters. 2 vols. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Pölzler, T & Wright, JC (2019) ‘Empirical research on folk moral objectivism’, Philosophy Compass, 14(5), e12589.

Sartre, J-P (1946) L’existentialisme est un humanisme. Les Éditions Nagel, Paris.

Shafer-Landau, R (2003) Moral Realism: A Defence. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Stanford, PK (2018) ‘The difference between ice cream and Nazis: Moral externalization and the evolution of human cooperation’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 41, e95.

Street, S (2006) ‘A Darwinian Dilemma for Realist Theories of Value’, Philosophical Studies, 127(1), pp. 109–166.

This question has been developed more formally in J. L. Mackie’s argument against the queerness of objective moral values:

If there were objective values, then they would be entities or qualities or relations of a very strange sort, utterly different from anything else in the universe. — Mackie (1977)

In their review of empirical studies on moral realism in the general population, Pölzler and Wright (2019) point out that whether people endorse realist positions depends heavily on how questions are framed and on context. When studies include a wider range of response options or highlight cultural disagreement, a majority of laymen often adopt non-realist views, treating moral judgements as dependent on personal or cultural perspectives rather than as reflecting objective moral facts.

To be accurate, not all moral realists adopt the position that moral laws are like laws of physics.

Note that there is a range of different defences of moral realism. To give this view a fair assessment within the limited space of this Substack post, I focus on two of its most influential supporters, Parfit and Harris.

An early title for his book was “Climbing the Mountain”.

Parfit would not describe this as appealing to “deep feelings”, but as using rational insight into what we have most reason to do. However, what he calls “rational insight” is still expressed through our considered moral intuitions, which are precisely what the theory is built to fit.

From a naturalist point of view, we can think of intuitions as designed to help us make good decisions in a rich world. In particular, we have quite good explanations of why creatures like us would have strong and systematic moral intuitions – roughly, because they helped our ancestors manage cooperation, conflict and punishment.

On that foundation, he then builds reasoning about moral facts:

Once we have a fund of prima facie justified moral beliefs to start from, there is great scope for moral reasoning to expand, refine, and even revise our moral beliefs, in exactly the manner that the contemporary literature in philosophical ethics displays. — Huemer (2005)

Let’s suppose there are indeed objective moral truths. Street (2006) considers two possibilities for our moral intuitions to track these truths:

Our moral intuitions were shaped the way they were because they track these moral truths.

Our moral intuitions were shaped the way they were without regard for these moral truths.

The first case does not fit what we know about evolution, which only pushes organisms toward fitness maximisation. The second case means there is no reason to expect our moral intuitions to have landed on these supposed moral truths.

Harris initially defines values as

the set of attitudes, choices, and behaviors that potentially affect our well-being, as well as that of other conscious minds.

This fully behavioural definition does not, by itself, imply that there is some value out there that has to be found. But saying, “value must be X, because no alternative works,” seems to shift the definition of value to something substantive, which must exist beyond our attitudes. Harris can then say that:

it is objectively true to say that there are right and wrong answers to moral questions

since moral questions are about something real: value.

For economist readers there is an interesting parallel with the theory of the value of goods. In the past, economists believed that there was a “value” embedded in goods, a kind of property that came with the good. But the theories of value faced too many issues. For instance, what is more valuable, a diamond or a glass of water? Our tendency would be to point to the diamond right away. But what if you were dying of thirst in the desert and offered either one or the other? You’d likely take the glass of water, as you’d have little use for the diamond to survive.

This diamond-water paradox and other such problems led to the abandonment of theories of objective value in the 19th century by the marginalists. The radical idea they adopted is that there is no objective value in goods. Value is only in the eyes of the beholder: we give value to things to the extent that we want them, that is to the extent that they give us utility. Hence, a diamond will have lots of value when I already have lots of water, but if I am dying of thirst, I will give a higher value to the glass of water.

You would likely not be convinced if I told you that pretty much everybody likes chocolate, so there must be an absolute value in chocolate.

I fully understand the appeal. As I’ll discuss in a later post, our cognition has likely been shaped by evolution to find the idea of objective moral truths compelling. Note that these arguments are not the only or necessarily the main ones made by philosophers, but their use is nonetheless telling. A preference for a conclusion should, if anything, count against that conclusion because we should be more sceptical about our propensity to impartially assess the evidence in its favour.

He admits that his motivation starts, before any reasoning, from the desire to prove that morality is objective:

I suspect that as a psychological matter, I hold the metaethical and metanormative view I in fact hold not because of highly abstract arguments in the philosophy of language, say, or in the philosophy of action, or because of some general ontological commitments. My underlying motivations for holding the metaethical view I in fact hold are – to the extent that they are transparent to me – much less abstract, and perhaps even much less philosophical. Like many other realists (I suspect), I pre-theoretically feel that nothing short of a fairly strong metaethical realism will vindicate our taking morality seriously. — Enoch

This point is a clear appeal to the Santa Claus fallacy. In another part of his book, he however acknowledges that such a dislike for anti-realism does not formally prove that it is false.

We are now in a position to see how belief in anti-realism undermines morality. It undermines both our moral beliefs and our motivation for behaving morally. This fact does not show that anti-realism is false. But it shows that, if anti-realism is false, it is also pernicious. — Huemer

The appeal to consequences often even takes a moral tone:

Moral realism―the view that there are objective moral facts, to which we have reliable access―is often defended with moral arguments. Only realism, it is argued, can make good on commitments that we hold most dear, e.g. that genocide is wrong no matter what anyone thinks about it, while anti-realist views such as subjectivism or relativism have unpalatable consequences with respect to such first-order moral issues, so we have moral reason to accept realism. — Golub (2021)

But how can we prove that morality is objective by presupposing that morality justifies this stance? There is a circular proof: morality is real because morality (coming from where?) imposes on us the conclusion that it is.

Given that the existence of moral truths is often seen as a prerequisite for life to have meaning. My “tough-minded” post on happiness and the meaning of life is a relevant complement to the present post.

Something that always amuses me about moral realists: they assume that the "objective moral truths" that they hold so dearly just happen to correspond precisely to their own moral values.

But what if we (somehow) found out that the moral truth was that Genghis had it right: it is objectively best to slaughter one's enemies and rape their women? Would the moral realists all start saddling up the horses and riding out accordingly? Or would they perhaps start coming up with long-winded explanations as to why that can't really be the moral truth?

Kind of like how if you found out that Santa Claus wasn't coming down the chimney to give you presents, but to kill your parents... so you started trying to prove that Santa *has* to give out presents rather than gruesome endings.

A problem not faced by those of us who concluded that Santa doesn't exist.

Excellent post, Lionel. Very much agreed about Santa Claus fallacies and appeals to intuition being unproductive. I used to be an antirealist, but then I started getting curious why we talk about morality as if it were objective. It seems to me we have no good naturalist theory for why moral talk is objective if it’s not. Why do we need so much false talk? Wouldn’t evolution favor an accurate view of the kind of thing morality is? Then I realized that a good naturalist explanation for why moral talk is objective is that we are referring to objective things in the world: the objective triggers of our moral emotions, absent any biases, defects, or misinformation. This makes sense of our moral talk and explains why people who don’t share our moral judgments seem “inhumane,” like defective humans. Their moral emotions aren’t working properly—they’re psychopaths. Or they were fed bad information—they’re brainwashed. Curious what you think of this view. It is a weaker, more human-centric kind of moral realism than one typically sees, but it is a realism no less. And it requires no skyhooks.