No, religion isn't required for morality

Our moral sense precedes religious doctrines

In this series of posts, I tackle the big question of fairness and morality: what it is and where our moral sense comes from. In the first post, I discussed the idea of building a morality from the ground up, following a naturalistic approach, rather than one held up in the air with skyhooks based on religious or metaphysical assumptions. Before I go into the nitty-gritty of its details, I will first address the most common alternative views about morality. This post is about the relation between morality and religion.

Religion is one of the most natural justifications for the existence of objective moral truths. Sacred texts handed out to us by a superior divine being provide a seemingly natural origin to morality.

This idea is so prevalent that the absence of belief in God is associated with an anxiety about the absence of morality. Sartre, an atheist, pointed out this concern:

[It is] extremely embarrassing that God does not exist, for there disappears with Him all possibility of finding values in an intelligible heaven. There can no longer be any good a priori, since there is no infinite and perfect consciousness to think it. It is nowhere written that ‘the good’ exists, that one must be honest or must not lie, since we are now upon the plane where there are only men. — Sartre

This belief that God is necessary to hold together our desire for morality to mean something is often used to justify explicitly or implicitly the existence of God, in what I call a Santa Claus fallacy—”Santa must exist because it would be too horrible if he didn’t”.

Here I explain why the idea that morality requires religion gets things backward, not only does religion not clearly underpin our moral sense, it is most likely our moral sense which has shaped religions.

The Euthyphro dilemma

Sartre’s quote reflects a widely shared belief that it is the existence of God which justifies the existence of moral truths. But is it really the case?

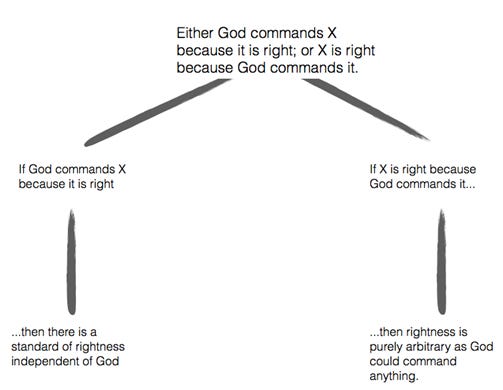

A problem with this idea was pointed out more than 2,000 years ago by Plato. In his dialogue Euthyphro, he presents a dilemma about morality and God. Is something moral because God said it is? Or does God give us injunctions to do something because it is moral?

If we accept the idea that something is moral because God said so, it makes morality arbitrary in the sense that we would have to accept as moral whatever God told us was moral. What if God told us that stealing or killing our neighbour is moral? To many, it would seem wrong for God to say that.

If, on the contrary, we say that God gives us injunctions because they are moral, then morality must be defined outside of God. In that case, we have not solved the question of the origin of morality.1

When religion conflicts with our moral intuitions

Evidence from psychology seems to suggest that believers behave as if they assume morality exists outside of God. This is illustrated by how they react to scenarios where God would recommend that we do things we unambiguously consider bad. Studying morality in children, psychologist Larry Nucci found that:

[…] the majority of children at all ages and from both religious groups rejected the notion that God’s command would make it right for a person to steal. […] Instead, children attempt to coordinate their notions of God with what they know to be morally right. — Nucci (1991)

He cites this interview with a conservative Jewish boy as an illustration:

Question. Let’s suppose that God had written in the Torah that Jews should steal, would it then be right for Jews to steal?

Answer. No.

Question. Why not?

Answer. Even if God says it, we know he can’t mean it, because we know it is a very bad thing to steal. We know he can’t mean it. Maybe it’s a test, but we just know he can’t mean it.

Question. Why wouldn’t God mean it?

Answer. Because we think of God as very good—absolutely perfect person.

Question. And because He’s perfect, He wouldn’t say to steal? Why not?

Answer. Well—because we people are not perfect, but we still understand. We are not dumb either. We still understand that stealing is a bad thing.2

A recent psychological study found that when asked whether it would be right for God to support a range of behaviour we typically reject, most children stuck to their moral norms instead of accepting the idea that they should simply follow a divine injunction.

Children of varying religious backgrounds identified moral norms… as authority-independent… even if God had made a commandment requiring people to steal, stealing would still be immoral. — Reinecke and Solomon (2023)

Another element in support of the primacy of our moral intuitions is that critics of religion often point to elements in them that conflict with our modern moral sense—like the justification of mass killings or of the inferior status of women.3 What would be the point of these criticisms if believers were just willing to accept that whatever God prescribes is the right thing to do? If critics resort to such criticisms, it is because they believe it will appeal to a moral sense that exists outside of religion and can be used to convince believers to disagree with religious teaching.

The cultural evolution of religions and how our moral sense shaped it

There are indeed good reasons to think that our morality precedes religion: our moral sense is a tool to help us navigate social interactions and cooperate successfully with others without being pushovers. Nicolas Baumard developed precisely this view in his book The Origins of Fairness:

Our moral disposition is specialized, autonomous, universal, and innate because it was selected by evolution. — Baumard (2010)

It is then not religion that gave us our moral intuitions, but our moral intuitions that helped shape religions. In support of this view, one can first observe that religions are incredibly diverse and that many forms of religion observed across times and places differ radically from the large monotheist religions we are accustomed to.

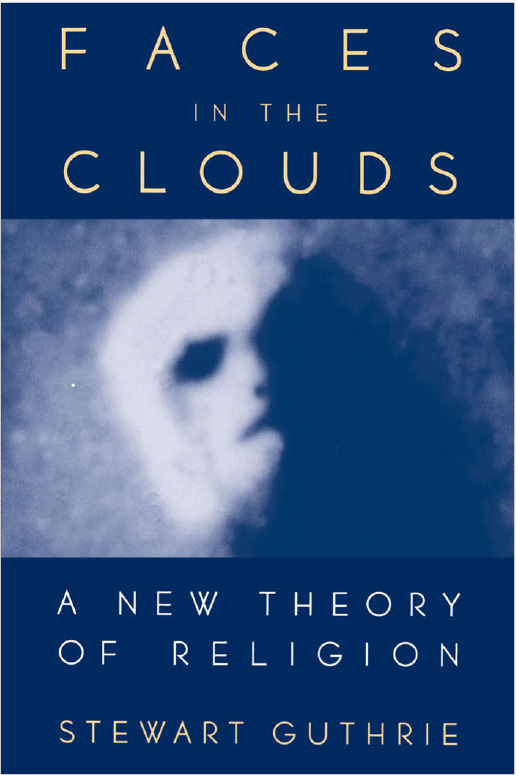

The anthropologist Stewart Guthrie discusses this diversity in his book Faces in the Clouds. This kind of comparison is useful to rule out some simple explanations of why religion arose in the first place.

Religion does not simply emerge to offer us a belief in an afterlife, because many religions do not place much weight on a consoling afterlife, and, in others, the afterlife is barely articulated or quite bleak.

Religion cannot have simply emerged to make sense of the world in some grand or ultimate way, because many religions are largely this-worldly and pragmatic, concerned with local misfortunes rather than with providing a comprehensive cosmology.

Religion cannot be simply about making us moral either, because many religions do not prescribe systematic moral behaviour, and some famous gods (such as the Greek gods) show little intrinsic interest in morality.

What Guthrie suggests is that religions arise, at least in part, from our evolved propensity to over-detect agency in the environment: we quite literally tend to see faces in the clouds. From an evolutionary point of view, this bias is useful because the cost of a false positive (thinking there is an agent when there is none) is usually small, while the cost of a false negative (failing to notice a predator, rival or ally) can be fatal. In ambiguous situations, it is therefore adaptive to be overly susceptible to assuming that some agent might be present. That is why we find creaking noises in old houses creepy and why we might jolt at the sound of leaves rustling in the bushes.

Guthrie’s claim is that religious concepts build on this general tendency: once the mind is primed to interpret ambiguous patterns as agents, it is a short step to populating the world with invisible persons, spirits and gods.

The anthropologist Pascal Boyer builds on Guthrie’s idea and argues that this propensity to over-detect agency helps explain the appeal of spirits and gods as minimally counterintuitive agents: agents that respect most of our intuitions about behaviour and even physics, with a few notable exceptions such as being invisible or able to perform miracles. Boyer suggests that religious traditions naturally blend such agents with our moral and social intuitions, so that gods and spirits have desires, likes and dislikes, form bonds with us, and take revenge if we break these bonds.

As such stories evolve, some themes are likely to act as cultural attractors4 because of how they resonate with our existing intuitions and preferences. This seems to be the case for moralising gods,5 who justify and enforce our moral sense. Moralising gods might be particularly appealing psychologically because they provide a justification for our feelings that good deeds should be rewarded and bad deeds punished. They satisfy our desire for a just world where no crime goes unpunished. Baumard and Boyer have argued that it is precisely this intuitive appeal that made such religious narratives historically successful.

Despite their differences, religious and non-religious movements owe their cultural success to the fact that these explicit, coherent accounts of moral prescriptions are congruent with universal, and much older, evolved moral intuitions. — Baumard and Boyer (2013)

In addition, moralising gods can help make societies more cohesive and cooperative, and therefore more successful. By creating beliefs that justify cooperative behaviour and increase the perceived costs of anti-social behaviour, moralising gods might help societies sustain a higher degree of social trust and a higher level of cooperation.6 In his sociology of religion, Max Weber has emphasised that one of the reasons for the economic success of Protestants was the effect of an ever-judging God (with the absence of the regular process of forgiveness of confession present in Catholicism):

[The puritan Protestant was characterised by] trust, especially his economic trust in the absolutely unshakable and religiously determined righteousness of his brother in faith. — Weber 1915

The game-theoretic foundations of our morality

So instead of religions being the foundation of our morality, it is our moral sense that likely led large world religions to evolve progressively into their moralising form. In support of this view, we have very good ideas about why our moral sense has precisely the features it has.

One of the most striking findings of the research in game theory in the second part of the 20th century was that it is rational to cooperate in repeated interactions7 and that very simple strategies like tit-for-tat (being kind to people who have been kind to you and not being kind to those who have not).8 The reason is simple. When people interact over time, being uncooperative now risks losing the gains from cooperation later. In his book The Evolution of Cooperation, Robert Axelrod stressed how the shadow of the future can make honesty and cooperation the best policy.

These findings left, however, one issue unresolved: there are many ways to cooperate and each way is associated with different splits from the gains of cooperation. Alice and Bob might be happy to form a family, but to have a happy and functional family they need to split the house chores, the childcare duties, the income-generating activities, and so on. There are many ways to split these things, and 50-50 everywhere is not necessarily a feasible or preferred solution. To start with, Alice cannot share the long and difficult process of making children with her partner, and she might expect him to pull his weight in other domains.

A key insight from game theorist Ken Binmore is that agreeing on how to organise cooperation, and split the gains it generates, involves some bargaining. He developed a theory where a key cognitive tool to solve this problem is for us to put ourselves in the shoes of other people, to take their side to be able to propose solutions that would be agreeable to all.

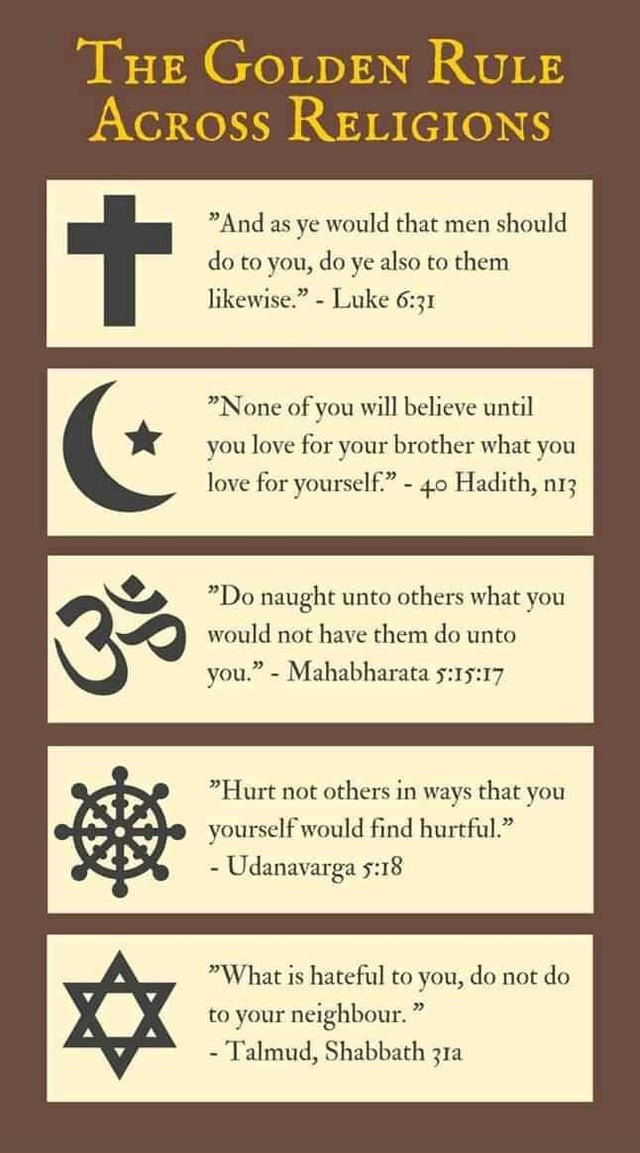

This cognitive tool is nothing else than the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”9 A striking aspect of this rule is how it can be found in pretty much the same form across widely different cultures and religions.10

It can also be found in secular ethical philosophy. Kant’s categorical imperative can be understood as a sophisticated elaboration of the Golden Rule:

Act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law. — Kant (1785)11

And John Rawls presents the original position with its veil of ignorance as a procedural way of applying Kant’s categorical imperative to the choice of social rules.

The original position may be viewed, then, as a procedural interpretation of Kant’s conception of autonomy and the categorical imperative within the framework of an empirical theory. — Rawls (1971)

Binmore thinks that such philosophies have been attractive because the Golden Rule, which he sees as a “simplified version of the original position,”12 is a fundamental principle of our psychology to navigate social interactions and negotiate with others. In short, we put ourselves in other people’s shoes to find a solution that works for all.13

For me, the original position is merely a stylized representation of a fairness norm that evolved along with the human race for the purpose of resolving small-scale coordination problems. — Binmore (1998)

In that perspective, it is not just reciprocity that is one of the foundations of our psychology; it is also about how we organise this reciprocity to coordinate on mutually agreed solutions. These deep intuitions exist universally because they are solutions to problems of cooperation faced for eons by our ancestors. Our moral sense is based on these deep intuitions. They do not derive from religion; instead, they shaped world religions.

In his article on Morality and religion in the Encyclopedia of Religion, Ronald Green observed the uncanny commonalities of religions’ moral principles in spite of their large diversity in traditions and beliefs.

One of the most striking impressions produced by comparative study of religious ethics is the similarity in basic moral codes and teachings. […] It is sometimes assumed, because religious traditions hold widely different religious beliefs, that their ethics must correspondingly differ; what is remarkable, however, is that these great differences in beliefs apparently do not affect adherence to at least the fundamental moral rules. — Green (1987)

This striking commonality makes sense once we understand that it reflects deep moral intuitions that precede the existence of large world religions, because they are part of the cognitive tools evolution has handed us to be successful as part of a highly social species.

It is common to hear the concern that without religion, morality is impossible. This perspective gets things backward. It is not religions that induce moral motives in humans. Instead, our moral motives pre-existed religions and world religions built on these and gave them a supernatural justification.

References

Atkinson, Q.D. and Bourrat, P. (2011) ‘Beliefs about God, the afterlife and morality support the role of supernatural policing in human cooperation’, Evolution and Human Behavior, 32(1), pp. 41–49.

Axelrod, R. (1984) The Evolution of Cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

Baumard, N. (2010) Comment nous sommes devenus moraux: Une histoire naturelle du bien et du mal [English translation: The Origins of Fairness]. Paris: Odile Jacob.

Baumard, N. and Boyer, P. (2013) ‘Explaining moral religions’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(6), pp. 272–280.

Binmore, K. (1998) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 2: Just Playing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Binmore, K. (2005) Natural Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boyer, P. (2001) Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. New York: Basic Books.

Darwin, C. (1871) The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: John Murray.

Dawkins, R. (2006) The God Delusion. London: Bantam Press.

Green, R.M. (1987) ‘Morality and religion’, in Eliade, M. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Religion, Vol. 10. New York: Macmillan, pp. 92–106.

Guthrie, S. (1993) Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kant, I. (1785) Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Riga: Johann Friedrich Hartknoch.

Norenzayan, A. (2013) Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Nucci, L.P. (1991) ‘Doing justice to morality in contemporary values education’, in Benninga, J.S. (ed.) Moral, Character, and Civic Education in the Elementary School. New York: Teachers College Press, pp. 21–39.

Plato (c. 399 BCE) Euthyphro. In: Cooper, J.M. (ed.) (1997) Plato: Complete Works. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing.

Rawls, J. (1971) A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Reinecke, M.G. and Solomon, L.H. (2023) ‘Children deny that God could change morality’, Cognitive Development, 68, Article 101393.

Roes, F.L. and Raymond, M. (2003) ‘Belief in moralizing gods’, Evolution and Human Behavior, 24(2), pp. 126–135.

Russell, B. (1927) Why I Am Not a Christian. London: Watts & Co.

Sartre, J.-P. (1946) L’existentialisme est un humanisme. Paris: Éditions Nagel.

Sperber, D. (1996) Explaining Culture: A Naturalistic Approach. Oxford: Blackwell.

Trivers, R.L. (1971) ‘The evolution of reciprocal altruism’, The Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1), pp. 35–57.

Weber, M. (1904–1905) ‘Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus’, Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, 20–21.

Bertrand Russell discussed this exact question in his text Why I am not a Christian:

The point I am concerned with is that, if you are quite sure there is a difference between right and wrong, you are then in this situation: is that difference due to God’s fiat or is it not? If it is due to God’s fiat, then for God Himself there is no difference between right and wrong, and it is no longer a significant statement to say that God is good. If you are going to say, as theologians do, that God is good, you must then say that right and wrong have some meaning which is independent of God’s fiat, because God’s fiats are good and not bad independently of the mere fact that He made them. If you are going to say that, you will then have to say that it is not only through God that right and wrong came into being, but that they are in their essence logically anterior to God. — Russell (1927)

For a discussion of how our moral intuition can often conflict with religious and traditional injunctions, see Baumard (2010).

See, for instance, what Richard Dawkins wrote about the Old Testament in his book The God Delusion

The God of the Old Testament is arguably the most unpleasant character in all fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control-freak; a vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a misogynistic, homophobic, racist, infanticidal, genocidal, filicidal, pestilential, megalomaniacal, sadomasochistic, capriciously malevolent bully.

Notion coined by the cognitive scientist Dan Sperber (1996)

See Roes and Raymond (2003).

See Atkinson and Bourrat (2011) and Norenzayan (2013)

In parallel to this insight coming from game theory, the biologist Robert Trivers developed the theory of reciprocal altruism, which posits that reciprocity might have emerged as a way to foster cooperation for mutual benefits between individuals who are not necessarily related by family ties.

The effectiveness of tit-for-tat is, however, often exaggerated. It is not an evolutionarily stable strategy, and other strategies have been found to beat it.

Binmore’s version is slightly more sophisticated: “Do as you would be done by—if you were the person to whom something.” This version emphasises that you should do to others what they would like to be done to them, not what you would like if you were them. Hence, if you like coffee ice cream but they prefer chocolate ice cream, you should give them a chocolate one, not the coffee one, which you would personally prefer.

And beyond religions, in a wide range of small-scale societies:

[…] the Golden Rule is almost universally endorsed in primitive societies. Modern work on pure hunter-gatherer societies is equally striking in the strong parallels it has uncovered between the social contracts of geographically distant groups living in starkly different environments. — Binmore (2005)

In plain English: behave only in a way you think everybody else could do as well.

Binmore (2005, p. 139)

Interestingly, Darwin had already discussed our moral sense and the Golden Rule in The Descent of Man. However, while he saw moral emotions as shaped by evolution, he described the Golden Rule as emerging from our higher cognitive abilities.

The moral sense perhaps affords the best and highest distinction between man and the lower animals; but I need say nothing on this head, as I have so lately endeavoured to shew that the social instincts,- the prime principle of man’s moral constitution* - with the aid of active intellectual powers and the effects of habit, naturally lead to the golden rule, “As ye would that men should do to you, do ye to them likewise”; and this lies at the foundation of morality. — Darwin (1871)

Binmore, instead, sees the Golden Rule also as an evolved cognitive device. In short, we do not follow the Golden Rule because we use our supreme reason. We come naturally equipped with the intuition to put ourselves in other people’s shoes to respect what they want in our interactions.

“No, religion isn’t required for morality”

I agree that this is a true statement. And there is no doubt that many atheists and agnostics are in fact quite moral.

I like to think I am one of them.

But it does not change the fact that the substantial reduction in morality in our country and indeed the entire Western world - most notably and obviously in the former Soviet bloc countries, but by no means only there - has occurred simultaneously with a steep drop in religiousity.

And beyond this, many leftists are openly hostile to religion and many of them are openly hostile to “Judeo-Christian values”. This last is, if not completely equivalent to morality, a near-perfect proxy.

So just because your title is a true statement doesn’t mean that we don't have a massive problem in transmitting moral values now that religion and religiousity are treated with hostility by left elites.

Or that in fact said problem is the *biggest* problem we have regarding the loss of morality.

And not coincidentally, one of the biggest problems we have in maintaining civil society and the neoliberal (a.k.a. capitalist) system that has created and can continue to grow the world’s wealth and prosperity.

Thanks for tackling a contentious topic with clarity and honesty. This straightforward argument, which you’ve well articulated, has surprisingly lost ground in the last decade. The fact that moral necessity precedes religious doctrines (which differ and often conflict) doesn’t necessarily preclude a moral god or gods, but it does demonstrate how moral intuitions that facilitate a cooperative equilibrium can arise independent of scripture.