Morality without skyhooks

Shedding light on what morality is and how it works

In this new series of posts, I will tackle the big question of fairness and morality: what it is and where our moral sense comes from. Having addressed these questions and defined what “ought” means, I will then turn to what should be done in society.

Soon after they learn to talk, children seem to grasp one somewhat abstract notion: fairness. They are quick to decry the unfairness of many situations: how food is shared at the dinner table, how their parents’ attention is divided among siblings, or how their teacher treats them compared with other pupils. This early disposition to identify what is morally wrong1 and what should be done to make it right further develops as they grow up. In the adult world, normative statements are commonplace. Turn on the TV, and an intellectual will tell you that society should be like this or like that; a politician will say that it is not right for the government to act that way; and an activist will state that social justice requires a change in policy to improve society.

But wait a minute, what do all these statements mean? What does it mean to say we ought to do that, or that it is right to do this? Asking these questions might surprisingly reveal that we typically don’t have very good answers! And, even more surprisingly, experienced thinkers’ answers often rely on intellectual tricks, skyhooks, whose weakness is overlooked only because they deliver the kind of answer our intuitions find comforting.

In this post, and upcoming ones, I argue that we can build a theory of morality without such tricks, a theory consistent with our understanding of natural and behavioural sciences. This theory provides strikingly simple answers to the deep questions that have been asked in philosophy about morality.

Morality put to the toddler’s acid test

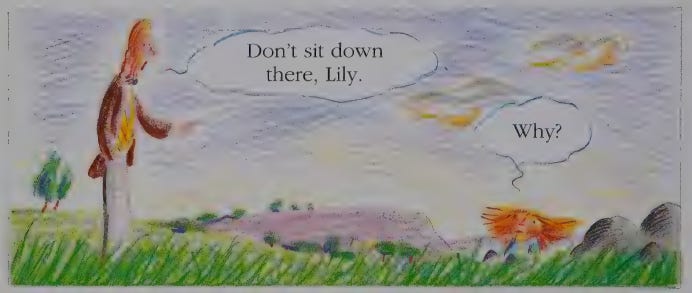

Because moral statements are so commonplace, it is easy to fail to appreciate how shallow our thinking about their meaning is. To see this, let’s put them to what I’d call the toddler’s acid test. Toddlers don’t know much, but they are often able to unsettle our confidence in our own “knowledge” with a simple trick: asking questions like “why?”, not just once, but repeatedly, until it becomes evident that we do not actually have all the answers.

Take a simple interaction from the 1990 children's picture book Why? In that book, a little girl, Lily, keeps asking “why?” to her father. Such an unrelenting line of inquiry quickly unveils the dangerously thin layer of knowledge on which adults’ daily confidence is actually based. Consider this possible exchange:

—Don’t sit down there on the grass, Lily.

—Why?

—Because it is not good to have stains on your dress.

—Why is it not good?

—Because you would not look respectable when our friends arrive.

—Why should I look respectable?

[Most dads who are not experts in the philosophy of social norms would start struggling here]

Adults typically end such discussions with “because that’s the way it is”, which is asking for faith in a pragmatic solution that works instead of providing a deep understanding.2

Now imagine a situation where the toddler asks a question about fairness. Let's say she observes on the news that a policy is implemented to increase the income of a category of the population. She inquires

—Why this policy?

—Because they face some hardship and the government is helping them.

—Why is the government helping them?

—Because it is good to help people who have difficulties.

—Why is it good to help people with difficulties?

In truth, most of us would struggle to articulate a meaningful answer to such a disarming toddler. In fact, many professional philosophers would too.3

The physicist Richard Feynman made a very interesting observation about “why?” questions: they are potentially endless.

When you explain a “why,” you have to be inside some framework that allows something to be taken as true. Otherwise, you’re perpetually asking “why.” — Feynman in an interview

One way to end the cycle of “why” questions about morality is to reach a solid and clear foundation. In the same way as mathematics can be grounded in initial statements, axioms, that are accepted as self-evidently true, one hope is that we can do the same about morality. Unfortunately, finding such principles, if ever they exist, has not proven easy.4 De facto, instead of relying on such foundations, theories of morality are often held by skyhooks.

Skyhooks

Skyhooks are explanations that hold our thesis in the air without any further grounding.5 The clearest example of skyhooks is the assumption that morality comes literally from the sky: its rules are handed to us by divine beings.

Examples of divine codes of morality are the Law Code given by the Sun-god Shamash to King Hammurabi, or the Ten Commandments given to Moses on Mount Sinai. Such stories seemingly solve the problem of the foundations of morality. You just have to look at the sacred book of your religion to find out the rules of morality.

A secular alternative is the idea that there are moral truths independently of religious beliefs. It is a widely held intuition that morality is somehow objective, as if there were absolute laws of morality, woven into the fabric of the universe, and which only need to be unveiled. The philosopher Grotius proposed a formal version of this intuition. He argued that humans have natural rights that emerge from natural laws that exist out there, so to speak.6 It is as if there were an invisible book of morality out there in the sky, only requiring us to find ways to recover its content.

Skyhooks have a big flaw: they are not grounded in anything. They therefore require a logical leap, a leap of faith. Why would we make such a leap? Often, the explanation is: because we want to.

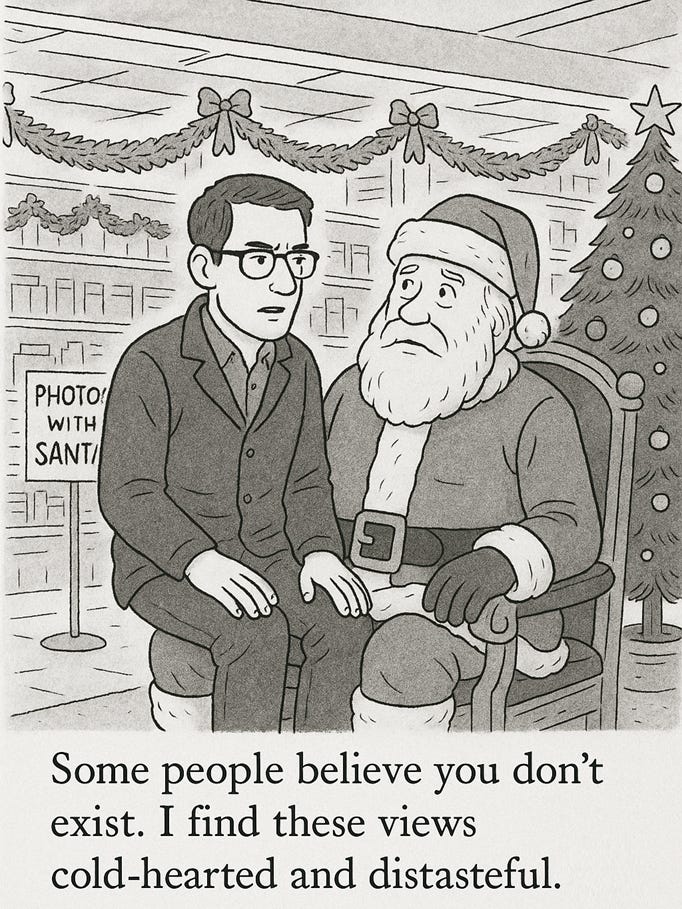

The Santa Claus fallacy

On issues of morality, one often hears as an argument something like: “it would be horrible if it were the case”. Versions of this argument take the form: “do you realise the implications of what you are saying?” or “This point of view is so cold-hearted” (i.e. you should not hold this view).

This argument is often made to justify the idea of God. A world without such a being would just be too horrible to think of. As written by Dostoevsky in The Brothers Karamazov: without God, everything is permitted. This argument is also used to back the existence of objective moral laws: “Why should there be objective moral truth? Well, imagine if moral truths did not exist, that would be horrible.”

This type of argument is called an appeal to consequences.7 I call it the Santa Claus fallacy because you can illustrate its absurdity with the case of Santa. Consider seven-year-old Alice, who starts wondering about the existence of Santa. Suppose that another kid points her to some piece of negative evidence, like the fact that Santa has too many kids to visit in one night. Weighing pro and con evidence, Alice decides to reject this counterargument, because it would be too sad if Santa did not exist. Clearly, that would be a reasoning error. Her preferences about the two states of the world—“Santa exists” and “Santa does not exist”—are irrelevant in determining which one is true. Given the fallacious nature of this line of argument, it is surprising how often adults are found using it.

Indeed, even expert philosophers juggling with abstract conceptual arguments are humans, all too human, and their apparently purely intellectual quest for the truth is often guided by strong underlying preferences about their final conclusions.

One of the most influential moral philosophers in recent times, Derek Parfit, is quoted in the introduction of his momentous 1400-page-long book on morality, On What Matters, saying:

it would be a tragedy if there was no single true morality. […] if we cannot resolve our disagreements, that would give us reasons to doubt that there are any true principles. There might be nothing that morality turns out to be, since morality might be an illusion. — Parfit (2011)

Parfit’s recently published biography8 even describes a scene where he made a clear appeal to the Santa Claus fallacy, during a course he was giving at Harvard in 2010:

He became visibly anguished when not all the students were convinced by his arguments about the objectivity of ethics. At one point, he fell to his knees, virtually pleading with the class: “Don’t you see, if morality isn’t objective, our lives are meaningless.”

Such appeals have a practical effect in arguments because reasoning evolved not primarily to find the truth impartially, as a scientist, but to justify our views and persuade others, as lawyers.9 The Santa Claus fallacy plays on this aspect of our reason: it is a rhetorical move that says, “come on, this is what you want to believe.” Once the listeners feel the pull of that appeal, they can use the flexibility of human reasoning to reinterpret conflicting evidence until it fits the preferred conclusion.10

Morality without skyhooks

What are we to do if we do not take a moral realist perspective held by some convenient skyhook? Are we bound to end up condoning egregiously unkind and violent behaviour? Are we paving the way for society to be the scene of a Hobbesian battle royale, where all are at war against all?

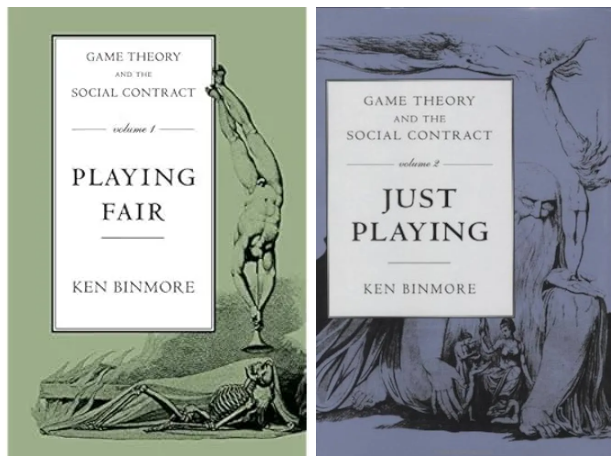

Binmore’s Game Theory and the Social Contract

Do not worry, this is not where we are going.11 Instead, we will build a different understanding of morality. The perspective I will take is naturalistic. It will largely be inspired by the work of game theorist Ken Binmore in the two volumes of his Game Theory and the Social Contract (1994-1998), later summarised in Natural Justice (2005). I view these books as among the most insightful and enlightening about political philosophy in the last 40 years. Unfortunately, they are little known outside of narrow economic circles. Binmore’s writing style is lively and entertaining, but it is also often technical and not easily accessible to the non-expert in game theory. It is a pity, as Binmore’s framework provides conceptual keys that unlock many of the most important questions of political and moral philosophy. Big mysteries about morality, what it is and how it works are seamlessly resolved.

A primer on Binmore’s theory of fairness

Instead of holding up a theory of morality with skyhooks, Binmore builds it up from the ground up with what Dennett called cranes:

Cranes can do the lifting work our imaginary skyhooks might do, and they do it in an honest, non-question-begging fashion. — Dennett (1995)

Cranes are built on our understanding of human behaviour and social relations. A naturalistic perspective on morality starts from a fundamental premise: humans are a social species composed of individuals with imperfectly aligned interests. They live in social groups where both opportunities for conflict and cooperation are present.

While this world presents risks (e.g. betrayal), it also presents opportunities for substantial gains from cooperation. These gains can be reached by following rules that make cooperation mutually beneficial. These rules are equilibria of the social games we play: following rules of cooperation leads to win-win situations. Moral behaviour is not strange or hard to explain; it is actually rational. This perspective goes back to the philosopher David Hume:

The rules of equity or justice depend entirely on the particular state and condition in which men are placed, and owe their origin to that utility which results to the public from their strict observance. — Hume

Following Hume, a substantial literature has blended game theory with political and moral philosophy to explain the nature of the social rules of cooperation we follow.

One of the insights Binmore brings to this literature is the importance of bargaining. There are many rules that could support cooperation, and different rules are typically associated with different splits of the gains and costs from cooperation. As a consequence, choosing a rule to organise social cooperation involves some bargaining as different people benefit differently from different rules.

Consider Alice and Bob, who are married and have to decide every day who cleans the dishes after dinner. They both prefer their dishes to be clean in the morning. Let’s assume two things. First, given their preference for cleanliness, each would rather do the dishes themselves than leave them unwashed. Second, given their distaste for chores, each would prefer the other to do the dishes. As a consequence of these preferences, they would like to agree on a sharing rule, but both would, if anything, prefer one that gives them a lighter share of the work.12

There is a nearly boundless number of rules that would be better than no agreement: they could alternate every day, or split the task in any way they like (e.g. weekdays vs weekends, the first 15 days of the month vs the last 15). In fact, given their preferences, even a very unequal sharing rule, where one of them always does all the dishes, would still be preferable to leaving the dishes unclean. When choosing among these possible rules and their corresponding divisions of work, Alice and Bob are de facto engaged in a form of bargaining.

Now, bargaining can be tedious, and it would be time-consuming and frustrating if we had to haggle over every situation of cooperation. Imagine our lives if every mundane request unfolded like this:

Alice: Can you pass me the salt please?

Bob: What am I getting in return for my effort?

So to successfully handle these ever-present bargaining situations, we have evolved meta-rules: fairness norms that are shared and allow us to reach a joint understanding about what bargaining solution will be accepted by all in a given situation. Fairness norms help us coordinate on one among the many possible rules of cooperation.

When we make claims about fairness and unfairness, we are making moves in what Binmore calls the game of morals. Fairness norms are rules of the game of morals. The result of this game determines the practical solutions we will agree on to cooperate in the game of life. Why is it useful? Because we benefit from having a shared understanding of what other people will be willing to agree to, and, similarly, they also know what we would be willing to agree to. This shared understanding can be leveraged in everyday situations for us to make the kind of propositions we know others will agree to (i.e. “Let’s alternate the dishes every day” or “I’ll do more of the dishes because you tend to work late”).13

Our moral sense reflects a cognitive architecture built to handle such problems. We have moral intuitions and emotions that help us play the game of morals well with others in order to go through the game of life seamlessly. Our psychology is well-tuned to identify “fair” solutions and recognise violations of the rules of the game of morals, so as to call them out.

That is why children very quickly learn to say “it’s unfair” without being moral philosophers. In the same way as their brain is equipped with intuitive physics, which helps them throw a ball and catch it without having studied Newtonian mechanics, they have moral intuitions that help them navigate their social interactions without having read a philosophy textbook.14

This naturalistic theory of morality clarifies what fairness and moral norms are and why we have our moral intuitions. In this series of posts, I will aim to present intuitively, and simply, Binmore’s key insights. Along the way, I touch upon many discussions by philosophers like Kant, Rawls, Dworkin, Parfit, Scanlon, Hare, Taylor, Singer, Nozick, and others.

Binmore said he was tempted to subtitle his book "Life, the Universe and Everything." This hints at the intellectual ambition of his enterprise.

Asking “why” questions repeatedly about morality and its origin typically reveals that we don’t have foundational answers. Often, the definitive answers provided rely on skyhooks: religion, natural rights, and so on. It is, in a sense, surprising how often we use the terms “ought”, “fair”, “moral”, without a proper grounding for them. In the same way as we can navigate the world with our intuitive physics without a proper understanding of fundamental physics, we can navigate the social world with its social laws with an intuitive morality without a proper understanding of the foundations of morality.

However, while our intuitive morality is very effective for most of our mundane social problems, it might fail to help us solve complex problems like building sustainable institutions in modern countries where people live in multi-million-inhabitant cities. Understanding the foundations of morality is therefore not only interesting in itself, but also useful for conceiving how to shape modern societies for them to work well.

References

Alexander, R.D. (1987) The Biology of Moral Systems. Aldine de Gruyter, New York.

Basu, K. (2018) The Republic of Beliefs: A New Approach to Law and Economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Bentham, J. (1843 [1795–1796]) ‘Anarchical Fallacies: Being an Examination of the Declarations of Rights Issued During the French Revolution’, in Bowring, J. (ed.) The Works of Jeremy Bentham, vol. 2. William Tait, Edinburgh, pp. 489–534.

Bicchieri, C. (2006) The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Binmore, K. (1994) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 1: Playing Fair. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Binmore, K. (1998) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 2: Just Playing. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Binmore, K. (2005) Natural Justice. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Camp, L. & Ross, T. (1990) Why? Andersen Press, London.

Dennett, D.C. (1995) Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life. Simon & Schuster, New York.

Edmonds, D. (2023) Parfit: A Philosopher and His Mission to Save Morality. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Grotius, H. (1625) De jure belli ac pacis libri tres. Paris.

Hume, D. (1739–1740) A Treatise of Human Nature. 3 vols. Macmillan, London.

Kant, I. (1788) Kritik der praktischen Vernunft. Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, Riga.

Lewis, D. (1969) Convention: A Philosophical Study. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Mercier, H. & Sperber, D. (2011) ‘Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34(2), pp. 57–74.

Ostrom, E. (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Page, L. (2022) Optimally Irrational: The Good Reasons We Behave the Way We Do. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Parfit, D. (2011) On What Matters, vol. 1. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Pölzler, T. & Wright, J.C. (2019) ‘Empirical research on folk moral objectivism’, Philosophy Compass, 14(5), e12589.

Sidgwick, H. (1874) The Methods of Ethics. Macmillan, London.

Ullmann-Margalit, E. (1977) The Emergence of Norms. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Moral issues encompass more situations than issues about fairness, so here I’ll lump the two and I will address the difference in a later post.

The same initial question could also lead to a series of queries about the natural world with the same final outcome: because it is wet—why?—because it rained—why?—because there were big dark clouds yesterday—why?—[non-meteorologist dads drop from the discussion here].

Readers would be within their rights to point out that what I call the toddler’s acid test is very similar to Socrates’ approach. In the Apology, Socrates recounts that, while he was still a stonemason, his friend Chaerephon asked the Delphic oracle who was wisest, and the Pythia replied that no one was wiser than Socrates. Puzzled, Socrates set out to test this by questioning politicians, poets, and craftsmen. By repeatedly asking questions from a professed ignorance—something like the Columbo of philosophy—he gradually unravelled the confidence of those who thought themselves wise but whose views rested on epistemic sand.

I prefer the image of toddlers asking questions, because it is even more damning to be cornered by an ignorant toddler than by a cunning philosopher.

Sidgwick attempted to follow this axiomatic approach in The Methods of Ethics. While highly influential, his axioms have not been accepted as “self-evident” by moral philosophers.

The original definition of a skyhook is “An imaginary contrivance for attachment to the sky; an imaginary means of suspension in the sky.” (Oxford English Dictionary). The term was popularised in its philosophical meaning by Daniel Dennett in Darwin’s Dangerous Idea as a metaphysical or miraculous mechanism invoked to explain complexity, design, or purpose without grounding it in natural processes. He makes this interesting comparison about it:

The skyhook concept is perhaps a descendant of the deus ex machina of ancient Greek dramaturgy, when second-rate playwrights found their plots leading their heroes into inescapable difficulties, they were often tempted to crank down a god onto the scene, like Super man, to save the situation supernaturally. — Dennett (1995)

The idea of natural rights was famously derided by Bentham:

Natural rights is simple nonsense: natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense,—nonsense upon stilts. — Bentham

For the philosopher readers:

The appeal to consequences is the move of claiming that something is true because of its consequences. What I call the Santa Claus fallacy is broader: it is asking someone to believe a claim (or to raise their credence in it) because of the consequences if it were true, even without pretending to have proved it.

William James argued that, in some limited cases, a “will to believe” can justify adopting a belief when the option is live, forced, and momentous, and the evidence does not decide. Many contemporary philosophers, working within standard Bayesian decision theory, allow that preferences over outcomes can rationally influence thresholds for acceptance and action, but not the credences themselves. In Bayesian terms, expected consequences guide choice (via expected utility), but they do not change beliefs about the state of the world. In plain English: you can choose to act as if a claim is true because the pay-offs matter (as in Pascal’s Wager), but you cannot rationally increase your belief in the claim just because of those expected consequences. I take this view here: whenever consequences are invoked to justify changing belief itself, we face what I call the Santa Claus fallacy.

Edmonds (2023)

Mercier and Sperber (2011)

Another high-profile case of the Santa Claus fallacy is often attributed to Immanuel Kant’s discussion of God in the Critique of Practical Reason. He argues that the highest good is possible only if God exists; hence, we need to assume that God exists:

The summum bonum is possible in the world only on the supposition of a Supreme Being […] it is morally necessary to assume the existence of God. — Kant

Philosophers are divided in their interpretation. Some charitably read Kant as making a practical argument: we ought to act as if God existed (“assume”), given the consequences for pursuing the highest good. This interpretation is compatible with Bayesian decision theory, since it concerns acceptance for action, not a change in belief. I am inclined to be less generous, as Kant does not say this explicitly. His statement, therefore, invites many readers to treat it as a reason to increase our belief that God exists, which is a Santa Claus fallacy.

I present these in Chapter 10 of Optimally Irrational (2022).

You have to understand this as “before any consideration of fairness” i.e. I am just saying that neither of them likes to do the dishes.

In the example of the interaction “Can you pass me the salt, please?”, the costs and benefits are small but nonetheless present. Fairness norms may give us detailed guidelines about when to accept gracefully (e.g. when the person is far away and the salt is within our reach), when to express some discontent at the request (e.g. when the person has already made several requests before this one), and even when it is acceptable to refuse (e.g. when the salt is far away and the other person could just as easily fetch it themselves).

This perspective also explains why our moral intuitions might be misguided in some cases, in the same way as a study of physics can help us understand why our intuitive physics works most often but sometimes fails dramatically.

if you take away this kind of appeal to consequences theres basically nothing left of metaethics

Hi Lionel. I've had Binmore's Natural Justice on my reading list for a long time, I'm gonna push it to the top of the pile now. In any case, I think something like the contractualist / game theory approach must be right.

But one question/thought. A key part of morality is its phenomenology. There is a strong emotional element, and indeed you write that "We have moral intuitions **and emotions** that help us play the game of morals well with others in order to go through the game of life seamlessly" (my emphasis). Why? As you know, there are other social arrangements (e.g. institutions) that are also social contracts but don't have the same phenomenology as morality. Explaining this seems to me to be a key part of the story.

I sketched my own answer in this short comment on Pinsof.

https://www.everythingisbullshit.blog/p/utilitarianism-is-bullshit/comment/164507278