The delusion of political violence

Our fantasies about violence are an evolutionary mismatch

I interrupt my series on mundane topics to comment on big-picture questions surrounding the tragic political assassination of Charlie Kirk over two posts. In this one, I discuss how we likely over-fantasise violence as a way to settle political conflicts. In the next one, I’ll discuss the interplay between social power (including the threat of violence) and epistemic strength (the quality of arguments) in political debates.

In the wake of Charlie Kirk’s assassination, some (even if a minority) publicly cheered in approval. Observing these reactions, people on the right, and beyond, were understandably outraged.

This Substack is not about outrage but about making sense of the world we live in, and, in particular, the sometimes puzzling and strange aspects of social behaviour. In this post, I look into why such reactions are misguided. The glorification of political violence makes me think of this famous quote about Napoleon’s summary execution of the Duc d'Enghien, a potential pretender to the throne:1

It is worse than a crime, it is a mistake.

Our fantasies of violence as an evolutionary mismatch

Fantasies of political violence are a mistake, in the sense that they are not even advantageous from the perspective of those who hold them. They reflect a likely evolutionary mismatch between our psychological architecture and the modern environment in which we live.

Modern society rewards much more cooperation than violence

One of the key differences between our ancestral past and our present is the length of our time horizon when making decisions. It is much, much longer now. Think about our ancestors, who for eons lived in small communities, hunting and gathering food. For sure, they understood that life lasted decades. However, the time horizon practically relevant for them was relatively short.2

In such an environment, for most practical decisions, time horizons were anchored in seasonal and annual cycles.3 The human brain, designed to navigate successfully this type of decision situation, has been thrown into a very foreign world: the setting of modern large-scale urban societies. In this world, the time horizon that is practically relevant to humans has been stretched to incredible lengths. One mechanical reason is that our life expectancy has increased substantially. It is now around 80 in most Western countries.

The fact that the time horizon of interactions creates an opportunity for mutually beneficial cooperation is well-known to game theorists. The Folk Theorem states precisely this. As the time horizon gets longer, people are more and more able to approximate full cooperation. Take an extreme example and imagine two gangsters who would have no qualms robbing each other. If they have the opportunity to interact regularly over time (e.g. in a drug deal where one brings money and the other the substance) they can engage in regulated cooperation, respect rules and benefit from these interactions.4

Another, more fundamental, reason is that modern society is built around institutions that link present choices to distant consequences. Banks and pension funds, for example, allow people to set aside money now with the near certainty of reclaiming it decades later. Schools demand long years of early investment before productive work begins, but the benefits unfold over the course of a lifetime.

Other institutions make long-term cooperation easier to sustain. Modern legal systems, and the confidence that rules will be enforced, give people the security to enter into durable cooperative arrangements with a large number of people far from their close family circle. An employment contract, for instance, commits an individual to contribute to a collective endeavour in exchange for regular payment, often over an open-ended period.

The high levels of cooperation in modern society are made possible by rules that codify what people should do. A lot of these rules are informal social conventions. A small subset of them are formal laws. These rules are followed because deviating induces sanctions. Violating social conventions leads to loss of reputation and social opportunities (you lose your friends and you alienate people). Violating formal laws can lead to fines or prison.

Cooperation and civil interactions

The whole way of life we take for granted in civil society is a reflection of these high levels of cooperation. We walk unarmed every day in modern cities with little worry about being physically attacked. Traffic works with people ceding right of way to strangers all the time, according to formal and informal rules. We can buy food in the supermarket and eat it, being almost 100% confident that strict hygienic norms were followed to make it.

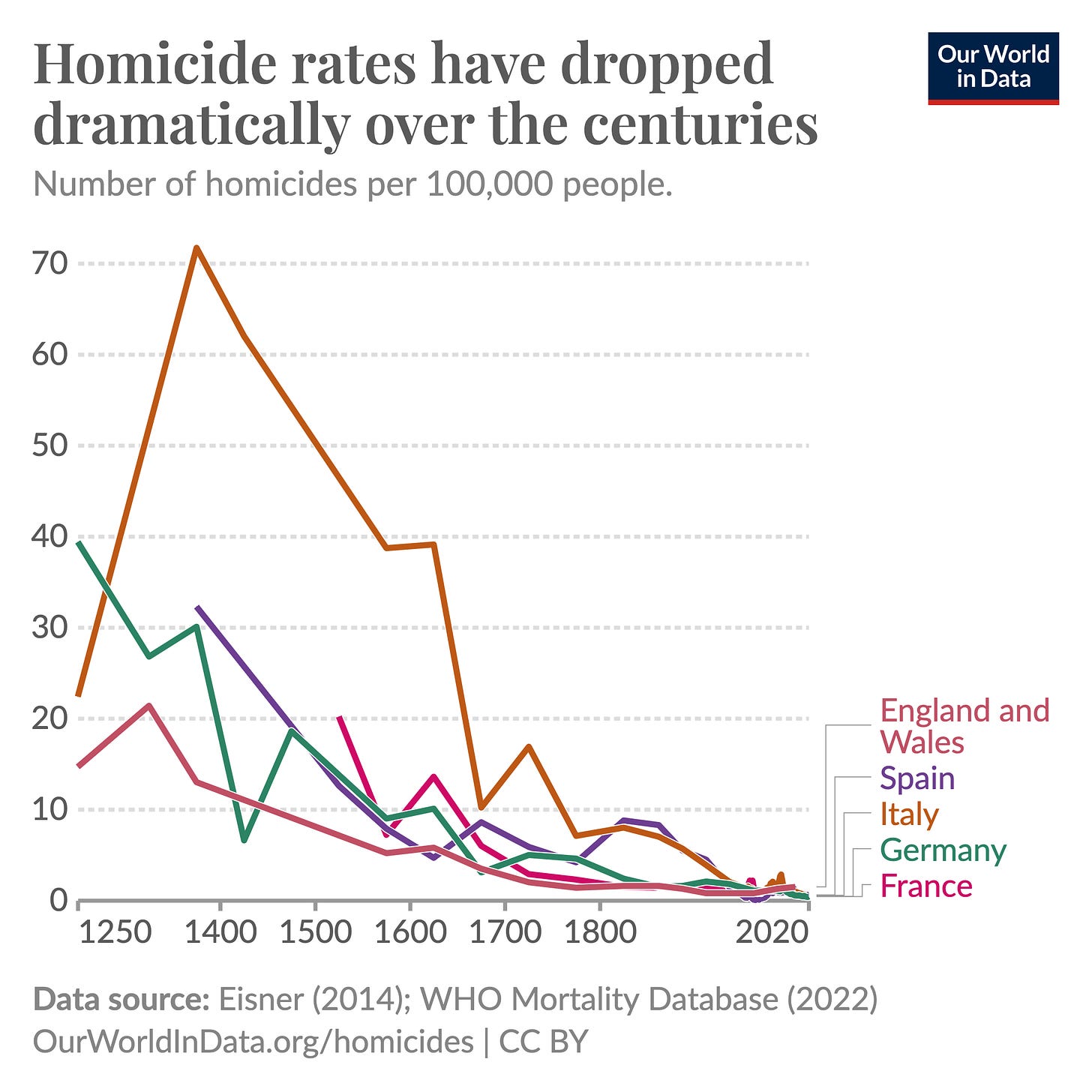

One fundamental aspect of social cooperation is the avoidance of physical violence, the common agreement to resolve disagreements by other means, such as arguing in a civil manner. That is why our modern societies have a historically low level of violence.5

In comparison, ancestral societies were relatively much more violent. You can forget about Rousseau’s vision of “noble savages”, living in harmony. The ethnographic evidence from small-scale societies presents a picture that makes seedy neighbourhoods of modern cities look like relatively safe havens. This is what I wrote in Optimally Irrational (2022):

The evidence on small-scale hunter-gatherer societies suggests a level of violence without comparison with our modern societies. The anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon famously estimated that, in the Yanomami, a tribe he studied in the Amazonia, nearly half of the males aged twenty-five or older had committed homicide and that a third of them ended up a victim of warfare or crime. — Page (2022)

Recent estimates suggest that the annual homicide rate in pre-agricultural societies was around 100 per 100,000, compared to an average of about 2 per 100,000 in OECD countries today.6 It is only over the more recent past that societies have become much less violent. Empirical data suggest that homicide rates were still many times higher in Europe over the period 1200-1600 than they are now.

The physical elimination of opponents was a practical option our ancestors were far more likely to adopt. In such an environment, their psychology was shaped to ensure survival, equipping them with emotional responses that could shift rapidly from cooperation to lethal aggression. Among these were impulses of raging anger and the urge to act violently.7

This psychological architecture explains why violent fantasies, while usually kept private, are surprisingly common. Psychologists have found that around two-thirds of people have entertained the idea of killing someone else at some point.8 However, our propensity to entertain violence is likely miscalibrated to our modern world, where the cost of violence is very high for the perpetrator.9

The evolutionary mismatch of modern fantasies of violence

A lot of violence is based on a hot temper flaring up. In the heat of the moment, people burst in anger and feel the urge to hurt others. Among homicides where circumstances are known in the US, a larger share are the result of arguments than of criminal activities such as robberies.10

Such bursts are typically “mistakes”, in the sense that people often regret them and would not engage in them if they had taken more time to think.11 Nowadays, a murder is rarely a “solution” to social conflict. It can lead to decades in prison, impacting not only your life but also those of your family.

The delusion of political violence

Placed in the domain of politics, our aptitude to fantasise about violence leads us to entertain strategies that would “work” if we could eliminate or at least physically subjugate our opponents. Leaving aside that we might oppose violence on moral grounds (i.e. it is a “crime”),12 it is a delusional take because it is not even a practical solution bound to lead to a desirable endpoint for those engaged in the violence themselves (it is a “mistake”).

In the modern world, violence is rarely associated with positive pay-offs for the person committing it. It either leads nowhere (violence seldom changes the views of a political opponent) or it leads to legal sanctions and possibly prison (if you injure or kill your opponent). In the case of Charlie Kirk’s assassination, the perpetrator, Tyler Robinson, has inflicted irreparable damage to his own life prospects and to his family’s well-being.

The fantasies of political violence are not just delusions because they will be too costly for the perpetrator. They are also misguided for the social consequences they are bound to generate. Political violence rarely works as a solution to improve society.

Consider the motto, heard sometimes in part of the left to “punch a Nazi”. What next after that? The “Nazi” will still be alive and able to vote, possibly able to come back and punch you too. Once physical elimination is off the table, you still have to share the society you live in with the people you committed violence against. Political violence is typically not the end of a conflict but the start of more tension and violence.

The use of political violence as a tool for change underappreciates the deeply cooperative nature of modern society, which relies on a shared web of conventions to resolve disagreements peacefully and to generate win–win interactions. This architecture scaffolds our lives. We do not see it because rules and norms just feel the right and natural thing to do.

Political violence is, in that perspective, an ill-suited candidate to improve society. In the same way as you are unlikely to repair the tightly organised cogs of a clock with a hammer, you are unlikely to improve the web of conventions about the mutually beneficial ways to cooperate in society using violent means. If anything, you are likely to break the things that were still working.

One of my favourite podcasts is Revolutions, in which Mike Duncan discusses the unfolding of major historical upheavals. Revolutions have something in common: they feature the breakdown of the social order as a result of the disruptive strategies of political actors. The typical scenario of a revolution is when the social compromise between different social groups becomes contested, and the parties fail to come up with a new civil agreement. Either slowly or abruptly, groups opt for steps towards political brinkmanship, breaking existing conventions and threatening further disrespect for rules and conventions, to get an upper hand in the reshaping of the social compromise.

This process, in the case of revolutions, spirals out of control. Then, too often, all hell breaks loose. The breaking down of social order leads to a Hobbesian state of nature where every party is at risk of political violence, and often opts to use it themselves pre-emptively. Mass executions and situations bordering on genocide often ensue.

We too easily ignore that the only reason society stays civil and well-ordered is our shared expectations that it will continue to work that way. The fact that the crumbling of the social order can lead to unexpected levels of violence and social pain was one of the major insights of the British philosopher Edmund Burke after the French Revolution. People who are willing to break the social conventions of civility to support their political views are putting in danger a social contract that, even if imperfect and often worth improving, benefits all.

Fantasies of political violence are delusions that divert from the type of strategies that are effective at resolving conflicts in the modern world. While disagreements can be deep and fierce, looking for a minimal common ground and peaceful ways to settle conflicts is likely more valuable in the long term.13

Whatever one thinks about Kirk’s positions, his modus operandi—to engage and argue with his opponents to win their minds—was a positive approach.14 He was, in particular, clearly right in making this observation in one of his debates:

When people stop talking, that’s when you get violence. — Kirk

For this reason, his murder is not just a tragic event at the individual level; it is also a corrosive political event, where violence (which might beget further violence) replaced words as a way to settle social disagreements.

References

Abrahms, M., 2012. The political effectiveness of terrorism revisited. Comparative Political Studies, 45(3), pp.366–393.

Auvinen-Lintunen, L., Häkkänen-Nyholm, H., Ilonen, T. and Tikkanen, R., 2015. Sex differences in homicidal fantasies among Finnish university students. Psychology, 6(1), pp.39-47.

Chenoweth, E. & Stephan, M.J., 2011. Why civil resistance works: The strategic logic of nonviolent conflict. New York: Columbia University Press.

Elias, N., 2000. The civilizing process: Sociogenetic and psychogenetic investigations. Rev. ed. Translated by E. Jephcott. Oxford: Blackwell.

Gurven, M. & Kaplan, H., 2007. Longevity among hunter–gatherers: a cross-cultural examination. Population and Development Review, 33(2), pp.321–365.

Jones, B.F. and Olken, B.A., 2009. Hit or miss? The effect of assassinations on institutions and war. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1(2), pp.55-87.

Kaplan, H. & Hill, K., 1985. Hunting ability and reproductive success among male Ache foragers: preliminary results. Current Anthropology, 26(1), pp.131–133.

Kenrick, D.T. and Sheets, V., 1993. Homicidal fantasies. Ethology and Sociobiology, 14(4), pp.231-246.

Pinker, S., 2011. The better angels of our nature: Why violence has declined. New York: Viking.

Rutar, T., 2024. Establishing an inverted U-shaped pattern of violence and war from prehistory to modernity: towards an interdisciplinary synthesis. Theory and Society, 53(3), pp.673-699.

Schelling, T.C., 1966. Arms and influence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Wasow, O., 2020. Agenda seeding: How 1960s Black protests moved elites, public opinion and voting. American Political Science Review, 114(3), pp.638–659.

The quote is commonly attributed to Joseph Fouché, Napoleon’s Minister of Police at the time.

Their experience of seasons must have made it useful to anticipate being prepared for the cold winters (e.g. stacking food), or to be ready for migrating herds to hunt. Their experience of aggression by other bands must have made it useful for them to make long-lasting decisions to adapt to this risk preventively (e.g. choosing camping sites that were easy to defend).

Note, however, that within these societies some activities did imply slightly longer horizons. Ache hunters, for example, lived from day to day in their subsistence, yet the advantages of skill in hunting were realised over years in the form of child survivorship and mating opportunities (Kaplan & Hill, 1985). Demographic studies also show that many hunter-gatherers lived into their 50s and 60s, long enough to raise children to adulthood and even see grandchildren (Gurven & Kaplan, 2007). These longer spans of consequence sat alongside the predominance of daily and seasonal cycles in decision-making.

Formally, consider a single interaction, like the drug exchange. If there is a probability that each time this interaction occurs it will re-occur in the future, then as this probability gets closer to one, two things happen. The expected duration of the interaction gets longer and the ability for players to reach higher pay-offs by cooperating increases. For instance, our gangsters might behave in a more trustworthy manner, which eliminates the need to check the drug or to get bodyguards for the transaction.

Note that the increase in cooperation over time is also due to the emergence of institutional solutions that generate incentives to cooperate by tracking violations of social rules in a more accurate way (e.g. traffic cameras, tax audits, use of DNA in criminal convictions). All these would have little effect if our horizon was very short, but conditional on our horizon being long, they allow us to coordinate society on higher levels of cooperation.

Rutar (2024).

This is not a value judgement on my part. It is not saying that deadly violence can be good. I am only talking about pay-offs, i.e. whether it is the one that is likely to deliver higher fitness outcomes in practice. This is a practical, empirical statement. A value judgement would require a normative theory of what is right and just. This is a topic for the next series of posts.

Kenrick and Sheets, (1993); Auvinen-Lintunen et al., (2015). The data were, it should be noted, collected using students as respondents, though there are no strong reasons to believe their answers would be much more violence-prone than the rest of the population.

To my knowledge, this specific evolutionary mismatch (our psychological architecture is tuned to a past where the benefits of violence were larger) has not been made in precisely these terms. However, one can see it as implied by the conjunction of two strands of literature. First, Sell, Tooby and Cosmides’ argument that emotions like anger are designed to successfully deploy the credible threat of violence in conflicts.

Anger is produced by a neurocognitive program engineered by natural selection to use bargaining tactics to resolve conflicts of interest in favor of the angry individual. The program is designed to orchestrate two interpersonal negotiating tactics (conditionally inflicting costs or conditionally withholding benefits). — Sell, Tooby and Cosmides (2009)

Second, Pinker recast Norbert Elias’s famous study of the civilising process and the decline of violence in terms of payoffs: harsher penalties from centralised states and greater benefits from cooperation in positive-sum games.

Commerce is a positive-sum game in which everybody can win; as technological progress allows the exchange of goods and ideas over longer distances and among larger groups of trading partners, other people become more valuable alive than dead. […] Life presented people with more positive-sum games and reduced the attractiveness of zero-sum plunder. To take advantage of the opportunities, people had to plan for the future, control their impulses, take other people’s perspectives, and exercise the other social and cognitive skills needed to prosper in social networks. — Pinker (2011)

In 2019, the FBI estimated that 43.2% of homicides for which circumstances were known were due to arguments, compared to 24.6% that were felony-type murders (murders during another felony such as robbery, burglary, etc.).

For that reason, killing someone in a bout of anger is qualified as manslaughter and substantially less penalised than premeditated and planned murder.

That would require having a theory of what is right and wrong. This is for my next series of posts.

Note that this does not mean violence is always ineffective at achieving some political goals. The assassination of autocrats has, for instance, been found to “produce sustained moves toward democracy” (Jones and Olken 2009). By contrast, work on terrorist attacks (Abrahms 2012) and violence in demonstrations (Chenoweth and Stephan 2011; Wasow 2020) has rather pointed to their ineffectiveness in achieving political goals.

It does not mean that he should be idealised. As pointed by Dan Williams, his support for Trump’s attempt to contest the result of the 2020 elections was not a positive approach to politics for a liberal democracy to remain functional.

Very interesting as always. The point about long term ignorance works not only for the future but also the past. People don’t take into account how arduous and complex the road to civilization was. They assume our current state is natural.

But, if our unconscious violent reflexes make us misadjusted to the modern world, it’s also true that our conscious expectations make us completely unprepared for the savagery of the old one. Almost everyone calling for aggressions would be lost if we went back to the law of the jungle.

Regarding long term strategies and the iterated prisoner’s dilemma, maybe you can confirm but I remember reading that tit-for-tat with a bit of forgiveness (to account for noise in the signals) was the best strategy -which shows how important candid cooperation is.

One small nitpick about the quote: “c’est pire qu’un crime, c’est une faute” is usually attributed to Antoine Boulay de la Meurthe although sometimes to Joseph Fouché (in his biography by Stefan Zweig)

This is an interesting text, but in my view it does not distinguish appropriately between personal and collective violence, and between institutional and insurgent violence. In particular, the comment on Burke and the French Revolution seems to me too much on the conservative side. The fact is that Ancien Regime elites opposed adamantly reasonable demands, and their institutional violence (including foreign intervention) contributed decisively to the spiral of violence that ensued. Arno Mayer, in his book "The furies", has countered this conservative narrative in a very clever way. We like it or not, actually existing liberalism required a one-hundred year violent dismantling of the Ancien Regime and its injustices and inequalities. It is hard to think about a realistic historical alternative to this (Burke did not tell us, I think), and it is surprising that modern liberals "repress" the very material conditions of what allowed them to become historically hegemonic.