Dystopia is closer than you think

We take our usual way of life too much for granted

In Back to the Future II (1989), an unfortunate change of events in the past leads to Marty coming back to a different present. In this alternative timeline, the US President, Biff Tanner, is a thuggish magnate ruling the country with an authoritarian and mafia-like style. The rule of law has broken down in the streets, with drive-by shootouts a common occurrence.

The eerily premonitory aspect of this part of the film, released 35 years ago, is that Tanner’s character was explicitly modelled on the image of Donald Trump.1 Beyond this, this part of the movie contains a deeper implication: we too easily take for granted the present way of life we are accustomed to, the fact that citizens are law-abiding and that institutions are somewhat functional. Instead, with the very same people living in the present society, things could be radically different in terms of social lawlessness, corruption, and violence.

In this post, I discuss how we take for granted the features of the world we live in, how things can quickly change radically, and what insight this gives into what is currently happening in the US.2

It’s all in our minds

All that stands between us and anarchy are the ideas that people carry around in their heads

Stop for a second in a supermarket and look around. Most likely, shoppers are politely respecting each other’s boundaries, putting their items in their cart and paying for them at the cash register. People follow an unspoken order: disputes are uncommon, violence is virtually absent, and theft is relatively rare. We take this as a normal situation. We behave that way because that's the way we are: reasonably polite, not too inconsiderate, and mostly law-abiding.

That view is an illusion. It takes one of the specific possible social equilibria, one on which society landed, as the natural state of the world, ignoring the many wild alternatives that could take place instead. In game theory, a social equilibrium describes a stable state of mutual expectations: people behave in certain ways because they expect others to do the same—and expect others to expect it, too. It is all, simply, in our mind. As put by game theorist Ken Binmore:

Those of us who live in bourgeois comfort need to be continually reminding ourselves that Nature has not provided us with any warranties for the continuation of our cozy way of life. All that stands between us and anarchy are the ideas that people carry around in their heads. Our property, our freedom, our personal safety are not ours because Nature ordained it so. We are able to hang on to them, insofar as we do, only because of the forbearance of others. Or to say the same thing a little more carefully: given society’s currently dominant but precarious system of conventions, we continue in the enjoyment of our creature comforts simply because nobody with the power to do so has a sufficient incentive to deprive us of them. Or, at least, not right now. - Binmore (1994) emphasis mine

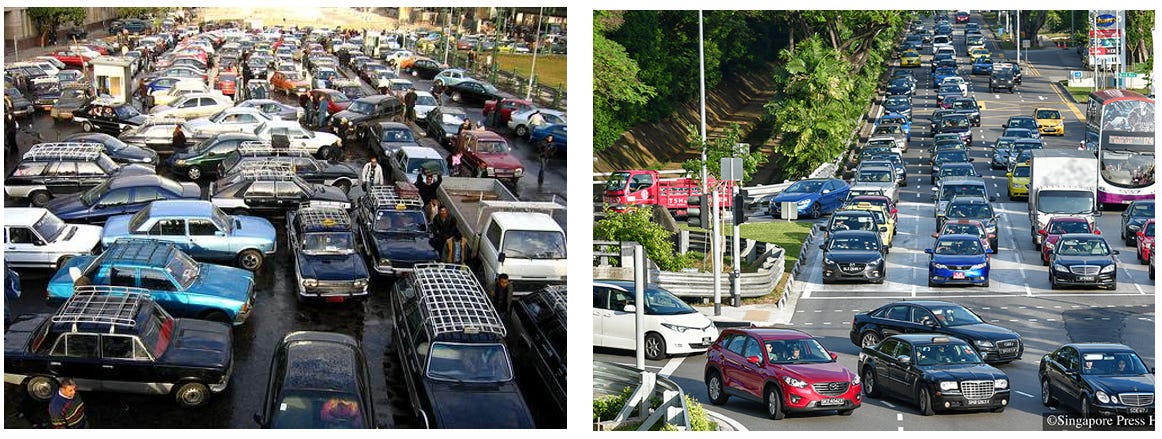

There are many social equilibria possible, and in each one, it is in people's interest to follow it. If you are driving in Cairo and everybody is fending for themselves on the road with scant regard for the official traffic rules, you would be silly to be the only one following them. If you are driving in Singapore, where most people closely abide by the driving rules, you would be wary about being the one breaking them.

Ken Binmore continues:

Such a bleak view of the way things are is admittedly simplistic. But is it so very far from the truth? If you doubt it, drive downtown to your local ghetto and watch what goes on when a community’s common history and experience fill people’s heads with a set of conventions and customs that are very different from your own. Or read a newspaper report about those countries in which the old common understandings have broken down and new common understandings have yet to emerge. - Binmore (1994)

Lesson: The way of life we are accustomed to in mostly peaceful, law-abiding societies with authorities respecting individual rights is not set in stone. Instead, it only exists because of what’s in our heads, and this can change.

This fact is illustrated in situations of crisis where the common confidence we have in generalised civility can break down. This possibility is often dramatised in disaster movies, where an external event leads to social order dissolving into riots, looting, and violence. The fact that firearm sales soared in the US at the onset of the COVID19 points to the fact that many people are aware of this possibility.3

The illusion of the strength of the law

A seemingly intuitive but misguided impression is that people behave well in their everyday lives because of the laws in society. The laws can be perceived to have constraining force because they define the behaviour to follow and imply sanctions for deviations.

But laws are only words on paper. If they have some binding power, it is only because they implement a social equilibrium. It is because people expect others to respect the laws that a law is respected. A law is binding only if it matches people’s expectations. Economist Kaushik Basu develops this point in his book The Republic of Beliefs (2018):

The might of the law, even though it may be backed by handcuffs, jails, and guns, is, in its elemental form, rooted in nothing but a configuration of beliefs carried in the heads of people in society. - Basu (2018)

Why do laws exist then, and what’s their function? They help to coordinate our beliefs by making one social equilibrium—specifying rules of behaviour in society and sanctions for deviations—more salient.

A successful law is one that shifts human behavior by creating a new focal point in the game we all play in life. - Basu (2018)

A law only has an impact if it reflects the way people already behave or if writing it down helps shift people’s expectations so they start following it. But if people are already strongly aligned around a different set of behaviours, simply putting a new rule on paper won’t change anything.4

Indeed, many laws exist that do not bind people because they expect that these laws will be ignored. In Cairo, driving regulations exist, but people do not respect them. In the U.S., it is still illegal to have an extramarital affair in 15 U.S. states, and it is a felony in three of them. In theory, a man found to have cheated on his wife could be sentenced to five years in prison in Michigan. These laws are, however, no longer enforced, and people who have extramarital affairs expect that only private costs will ensue if their infidelity is discovered.

The web of norms sustaining social order in liberal democracies

It is therefore not the writing of laws in legal codes per se that maintains the social order in liberal democracies. It is a web of conventions and expectations.5 In broad strokes, we can gather the web of norms that characterise liberal democracies in three categories.

The rule of law. Within the country, written laws are respected and enforced. Infringements are sanctioned by institutional actors (e.g. judges) and called out by actors of civil society. This rule of law goes beyond written law and includes, to some extent, established conventions. The rule of law relies only on our collective expectations that laws will be respected and deviations punished. The breaking of that rule of law can simply emerge as the result of these expectations breaking down.

The Constitution of Knowledge. A fundamental aspect of liberal democracy is that it features a network of social rules, institutions, and norms that collectively govern how we produce, validate, and disseminate knowledge. This system is not under the control of the political rulers, and it relies on institutionalised truth-seeking, where claims are subject to checking, scrutiny, and accountability. It features public norms that penalise systematic dishonesty, media institutions that fact-check and challenge falsehoods, and a culture that values truthfulness over tribal loyalty.6

The respect for international rules. The respect for the rule of law extends to international relations, with democracies typically respecting international rules, past commitments, and other countries’ borders. Deviations from such respect would be called out within the country and would be costly for the country’s leaders’ public support.7

These characteristics are not natural laws. Critics will easily find here and there examples of deviations. Rather, in practice, the respect for these rules tends to be a feature of democracies. It is not because democracies are inherently good, but because of their social equilibrium and the structure of incentives actors face in these societies.8 But this social equilibrium stands only because it relies on the collective expectations in our minds. As natural as these features might seem to people living in liberal democracies, they might vanish if these expectations fade away.

The US case

The general insights outlined above take on particular significance in light of current developments in the United States. Despite their well-known limitations and flaws, U.S. democratic institutions were, until recently, considered among the most robust in the Western world. The speed at which they appear to have weakened is one of the most striking lessons of the recent period.

The rule of law

Trump’s confrontational relationship with legal and institutional constraints is well established. His attempts to overturn the 2020 election results—by pressuring officials, political allies, and media—represented a historically unprecedented challenge to U.S. democratic norms. Since returning to office in 2025, he has gone further, most noticeably challenging judicial authority, including declining to comply with a Supreme Court ruling, and suggesting that he may seek a third term, despite the constitutional two-term limit.

This clearly tests the rule of law, which relies on shared expectations of compliance. Such behaviour coming from the White House, with the popular support it commands, directly undermines those expectations and weakens the institutions that depend on them to uphold the law.

Alongside formal challenges to the rule of law, pressure is also mounting on civil society institutions that traditionally act as counterbalances, law firms, media outlets, universities, and private companies. As these actors come under political influence or intimidation, their ability to support dissent and uphold independent norms weakens. This shift nudges towards a different social equilibrium: when legal defence is uncertain, public criticism risky, and institutional backing absent, resisting authority becomes costlier, and few are willing to be the first to stand up.

The enforcement of a society’s social norms does not rely solely on institutions, but also on the fact that deviations incur reputational costs and social sanctions such as blame and shunning. A striking change in the U.S. political system is the erosion of reputational consequences for a wide range of misbehaviour.

In the Republican Party, figures who once condemned Trump in the strongest terms now express loyalty to the point of sycophancy. This is not the result of ideological change but of shifting incentives: as Trump consolidated control over the party base, political success began to depend on personal allegiance.

The Constitution of Knowledge

A defining feature of Trump’s political strategy has been his willingness to repeatedly assert falsehoods, often brazenly and in defiance of clear evidence. In a healthy epistemic environment, such behaviour would be checked by institutions dedicated to truth-seeking—independent media, expert communities, and public norms of accountability. But in today’s hyper-partisan landscape, the credibility of these institutions has been weakened, on both sides of the political divide.

Partisan news media do not present facts objectively. Instead, they offer rationalisations for supporting one side and opposing the other. This undermines their role in holding politicians accountable for their actions and statements. The informational content of their assessment of politicians’ actions is close to zero, since they always reach the predetermined conclusion that their side is right and the other side is wrong.9

This comes at a time when the propensity to lie blatantly and openly has spread to large swaths of the Trump administration. The result is an epistemic crisis, with a severe degradation in the ability of knowledge institutions to constrain politicians from flouting the norms of intellectual honesty.

The respect for international rules

In foreign policy, too, previously prevailing norms have been shaken in unprecedented ways. Trump has floated territorial ambitions, including acquiring Greenland from Denmark, without ruling out military force. These statements were met on Fox News by anchor Jesse Watters with a martial tone that would not be out of place on Russian state television. What was once beyond the pale of serious discourse is now aired in national media and treated as a legitimate subject of partisan commentary.

How close?

In their 2018 book, How Democracies Die, political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt describe how democracies can decay and turn into autocracies. They point out that democracies most often die not through sudden coups, but through the gradual erosion of democratic norms by elected leaders who subvert institutions from within. The political equilibrium shifts progressively until the nature of the political system has radically changed.

Saying that social equilibria can shift is not saying that they are very likely to. Rather, it is simply pointing out that a social order that seems natural and immutable can break down. As a consequence, social dystopia is a possibility that we should never neglect. Being aware of this possibility and remaining vigilant about the signs of change is one way to help prevent it from happening.

American democratic institutions are, I believe, most likely to withstand, though not unscathed, the current test they are undergoing. If so, the current political episode should serve as a reminder that we easily take for granted the social order we live in. We are just one equilibrium shift away from an alternative present marked by the breakdown of the norms that characterise our present society.

References

Basu, K., 2018. The Republic of Beliefs: A New Approach to Law and Economics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hayek, F.A., 1973–1979. Law, Legislation and Liberty. 3 vols. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Levitsky, S. and Ziblatt, D., 2018. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

Rauch, J., 2021. The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Shannon, C.E. and Weaver, W., 1949. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

As stated by the writers in 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/10/simpsons-predicted-president-trump-back-to-the-future

I should add that this is a very different stance from the one—now surprisingly common in the West—that views Western democracies as already terrible places. The premise of this post is, instead, that Western societies over the past two decades are flawed in many respects but nonetheless offer some of the best ways of life on earth to their populations.

The malleability of human behaviour, and the possibility for ordinary people to adopt en masse behaviours far removed from the norms of polite society, became a major question after WWII, when the mass crimes of Nazi Germany were uncovered. Hannah Arendt, famously describing Eichmann during his trial in Jerusalem, spoke of the “banality of evil” to characterise a man who focused on doing his job efficiently as a civil servant—optimising train logistics to send hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children to their deaths in extermination camps.

Social psychologists published some of the most iconic studies on the topic. Asch’s study found that people’s judgments were highly sensitive to social pressure. Milgram showed that people’s willingness to harm others could be quite high when prompted by an authority figure. Zimbardo’s prison experiment suggested that almost anyone could become a torturer when placed in the right conditions of control and asymmetry of power.

Recent reassessments of these studies have tempered their original claims. It appears that, in Asch and Milgram’s experiments, several participants may have understood the setup and were simply playing along. In the case of Zimbardo, the findings were largely choreographed by the experimenter himself, and the study is now viewed as closer to a work of fiction than to a scientific investigation.

These studies had, nonetheless, an important message: our behaviour might be heavily shaped by our social environment. What was missing is the idea that what matters is the social environment’s equilibrium, based on expectations and norms.

A law can give the illusion of being a rule imposed from above. But when viewed as an equilibrium, legal rules are often simply the codification of norms already accepted within society. It is a key argument made by economist Friedrich Hayek that laws emerge from social rules. Discussing common law systems where judges create new rules through rulings, he writes:

The efforts of the judge are thus part of that process of adaptation of society to circumstances by which the spontaneous order grows. He assists in the process of selection by upholding those rules which, like those which have worked well in the past, make it more likely that expectations will match and not conflict. - Hayek (1973-1979)

The writing of laws can help solidify existing conventions and, at times, nudge society toward new ones. But the ability of laws to shape behaviour is limited.

The expression “the constitution of knowledge” was coined by Jonathan Rauch (2021).

This is not to claim that democracies are inherently good. Critics can easily point to instances of democracies violating these norms.

See my previous discussion of democracy as a system and why democratic regimes tend to be more peaceful than dictatorships.

A source contains information only if it can surprise you, that is if you do not already know what you are going to hear/see (Shannon and Weaver, 1949). Hence, a media that is by design always going to land on the conclusion that A is good and B is bad does not provide you with information about the respective quality of A and B.

I don’t necessarily disagree with your premise, but the piece reads as if the last four years simply didn’t happen. The paragraph about the supermarket, in particular, was puzzling, especially given how many stores now keep everyday items locked behind glass, requiring a worker to fetch a key just so you can buy toothpaste.

The idea that our institutions were running properly before Trump‘s reelectionalso struck me as odd. The Government Accountability Office reported last year that between 2018 and 2023, the federal government lost between $300 billion and $500 billion annually. We’re now running $1 to $2 trillion deficits. Is that supposed to be the new normal? And just this week, we learned that AmeriCorps has failed eight consecutive audits. I thought only the Pentagon could pull that off.

You also point to Trump’s lies as deeply concerning, but what about the 2021 claim that the COVID vaccine would stop the spread of the virus? That lie was used to justify vaccine passports and to fire people from their jobs for noncompliance. Yet that claim was debunked before 2021 even got started. In December 2020, the CEO of Moderna and the Chief Medical Officer of Pfizer both told Lester Holt in an interview that preventing transmission hadn’t been studied, and there was no data to support such a conclusion.

I didn’t vote in the last election for the first time in my life, but I’m glad the last four years are finally over. Every year, I kept thinking that we’d finally reach the top of peak stupid, only to realize that stupid has a lot of stamina. And I didn’t even mention the federal government’s dark turn against the first amendment.

This gets to the heart of what's most troubling about the newest episode of American politics. Although I don't think the overreaches of the liberal institutions (re Covid, identity politics etc.) were comparable to the blatant, foundational abuses by the current administration, I do acknowledge that they contributed to our current political degeneracy.

Yet, the response by the Republican party was not to re-orient those institutions who are judged to have strayed off from their path (what voters hope for when they elect you in a democracy), but to use it as leverage and an excuse to legitimize a bottomless pit of norm violations of their own. And *that* feels like a very steep path descending into dystopia. Asserting that "the decline had already started when the other party was in office" is a dangerous excuse no adult should take seriously, and it doesn't help make things any better.