Democracy without illusions: a realist view

Democracy is less about finding the true social good than managing conflicting interests

Our vision of democracy is deeply shaped by the example set by classical Athens—particularly the image of citizens gathering in the Agora, the central public space, to discuss public affairs and make collective decisions. This model of direct democracy, where citizens themselves debated and voted on laws, continues to inform the way we imagine democratic life: open deliberation, civic participation, and power exercised directly by the people.

This ideal representation of democracy is also associated with the idea that public deliberation is what allows citizens to determine and agree on the best course for society. Philosopher Jürgen Habermas's famous discussion of the role of the public sphere echoes this vision.

By “the public sphere” we mean first of all a realm of our social life in which something approaching public opinion can be formed. […] Citizens behave as a public body when they confer in an unrestricted fashion — that is, with the guarantee of freedom of assembly and association and the freedom to express and publish their opinions — about matters of general interest. - Habermas (1964)

In that perspective, open public deliberation is essential for identifying and implementing decisions that serve the common good. The initial hopes, and later disappointments, in the ability of social media platforms to create such a vibrant and productive public sphere reflect how our reality failed to match the ideal image we associate with democracy.

In this post, I explain why this vision of democracy is wrong. The idea that democracy is primarily about discovering and implementing a singular public good is misguided. Here I make a realist case for democratic institutions, based on what they are really good for: managing distributional conflicts in society, in a way that benefits most people.

Why the idealist view of democracy is misguided

There is not a single public good

The key misconception of the idealist view of democracy is that it overlooks the irremediable conflicts of interest existing in society. In the idealist view, a free public sphere will give citizens the ability to find out what the best decisions are for society.

This intuition is most often not explicitly stated but is definitely present. Besides the Greek image, it has certainly been influenced by ideas from the French Revolution. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a key intellectual influence on the French Revolution, famously developed the concept of popular sovereignty through his notion of the general will. He argued that the people of a society, taken as a collective body, can have a shared will oriented toward the common interest. Following that perspective, the role of democratic institutions is to foster the conditions under which the general will can emerge—a will that expresses what is best for the society as a whole.1

When, in the popular assembly, a law is proposed, what the people is asked is not precisely whether they approve the proposal or reject it, but whether it conforms or not with the general will that is theirs. - Rousseau (1762)

This view is misguided because there is not one “public good”, which only needs to be identified. The impossibility theorem from the economist Kenneth Arrow (1951) makes this point formally. In a society where people have different preferences, it is impossible to aggregate them into coherent, unified social preferences in a democratic way that allows everybody to have a say.2

Let’s be clear that some decisions are better overall than others. However, the key challenge of democratic institutions is typically not to find the true answer to these questions. Whenever people’s interests in society are aligned, there is often little need for public discussions. Instead, experts work out what seems to be the best solutions, and their suggestions are implemented because nobody opposes them.

If there are debates in society, it is because of all the situations where the incentives of different social groups are not aligned. Most political debates in democracies are not about finding a truth that everybody agrees on, they are about settling decisions in situations where interests conflict, and the final outcome will decide who gets what and who pays what. Should wages increase for the workers, or should prices stay low for the consumers? Should taxes on pensioners increase, or should their pensions be better indexed to inflation? Should this industry be subsidised and protected from international competition, or should cheap international products be allowed to flow into the country?3

The Agora is not a good model

The second misconception is to be too influenced by the Agora as an ideal model of democracy. In the past, the term “democracy” was often used pejoratively, signifying the rule of the rabble or of the mob. Who would want that? Certainly not Plato, who resented Athens’ democracy for having condemned to death his mentor Socrates.

Modern democracies are republics with layers of elected representatives and constitutional limits to their prerogatives, not direct democracies allowing any majority on the day to decide whatever they want.

Nonetheless, direct democracy is often perceived as the purest form of democracy, with delegation being a form of compromise. If the power is in the hands of “the people”, why introduce layers of representation and constraints that may lead the political system to be unresponsive to the desires of the majority or even be captured by a political elite?

The conception that there is something better in direct democracy is, however, also misguided. Anybody who has spent any time in organisations relying heavily on collective decisions with minimal delegation has gained a key insight about why: it is very time-consuming. This aspect has two main drawbacks. First, it uses the time of the organisation’s members that could be used in more enjoyable or productive activities. Second, it makes the organisation less able to quickly adapt to changing circumstances.

How democracy works

These ideal views on democracy are deeply entrenched in our intuitions, as they are associated with the narratives justifying the institutions in modern democracies. They are however misleading. It is true that some policies are better for all, but the idea that the primary goal of public policy is to pursue them ignores the irremediable conflicts of interest in society.

Political institutions solve both cooperation and conflicts in society

The role of political institutions is not, as Hobbes (1651) suggested in Leviathan, to prevent us from killing and robbing each other. Evidence from small-scale societies suggests that people close to what Hobbes called the state of nature were able to live very orderly lives without the need for a Leviathan leader to control them.

To understand the existence of political institutions, one should follow a more insightful path offered by Hume (1739) in A Treatise of Human Nature. Social rules exist because people can gain benefits from cooperating with each other. Whenever this cooperation takes the same form all the time—for instance, working together growing crops and harvesting them—social behaviour becomes ruled by social conventions that emerge over time. These conventions are equilibria of these social games.

One such convention is to delegate some decision-making to a single person whenever situations keep changing quickly over time. As put by game theorist Ken Binmore:

We invest authority in the captain of a ship for [that] reason. Who wants a debate about which crew member should do what in the middle of a storm? - Binmore (2005)

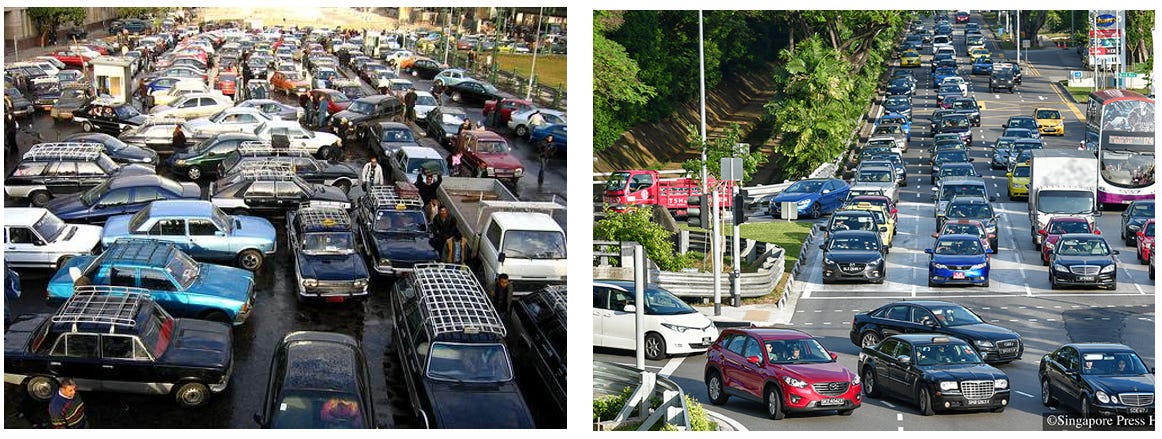

There is therefore a sense in which things can be better off for everybody: some social equilibria are better than others for everybody. A good example is the comparison of countries where nobody follows the traffic rules and a situation where everybody mostly respects them. These are two different social equilibria, but people are typically better off driving in the latter one.

Political institutions exist to secure these gains from social cooperation. But they have another function: there are plenty of ways these gains could be split and shared in society. A key role of political institutions is to organise how social gains are split and shared.4

Political institutions therefore have a dual role: finding good solutions and distributing their benefits. The distribution aspect is key; it explains why so much of the political debate is confrontational. It is because people have diverse interests about what should be done. Each part of the public defends its interests. Workers want their jobs to be safe, old people want their health services to be good, farmers want the price of their products to be supported, and so on. This is not the ideal of an agora, but it is the reality of collective decision-making in a society where people do not have perfectly aligned interests.5

Distributional conflicts as coalitional games

Because, in fine, the decision-making lies in the hands of a leader, or of a small group of leaders, political life revolves around the attempt to form winning coalitions that successfully put in charge and back leaders who defend their interests (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003).

Look beyond the good words about the public good—this is what politicians are doing (now consciously and systematically with their political experts): cobbling together a programme that can be supported by a winning coalition. It is no wonder political debates have limited efficacy in convincing others. As famously pointed out by the American politician Upton Sinclair:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it. - Sinclair (1934)

Rethinking democracy

What is democracy from that perspective? It is a form of political regime where the selectorate—the group of people who can take part in the decision of who will be in charge—is large (the voting citizens), and where their opinion is asked at frequent intervals (elections).

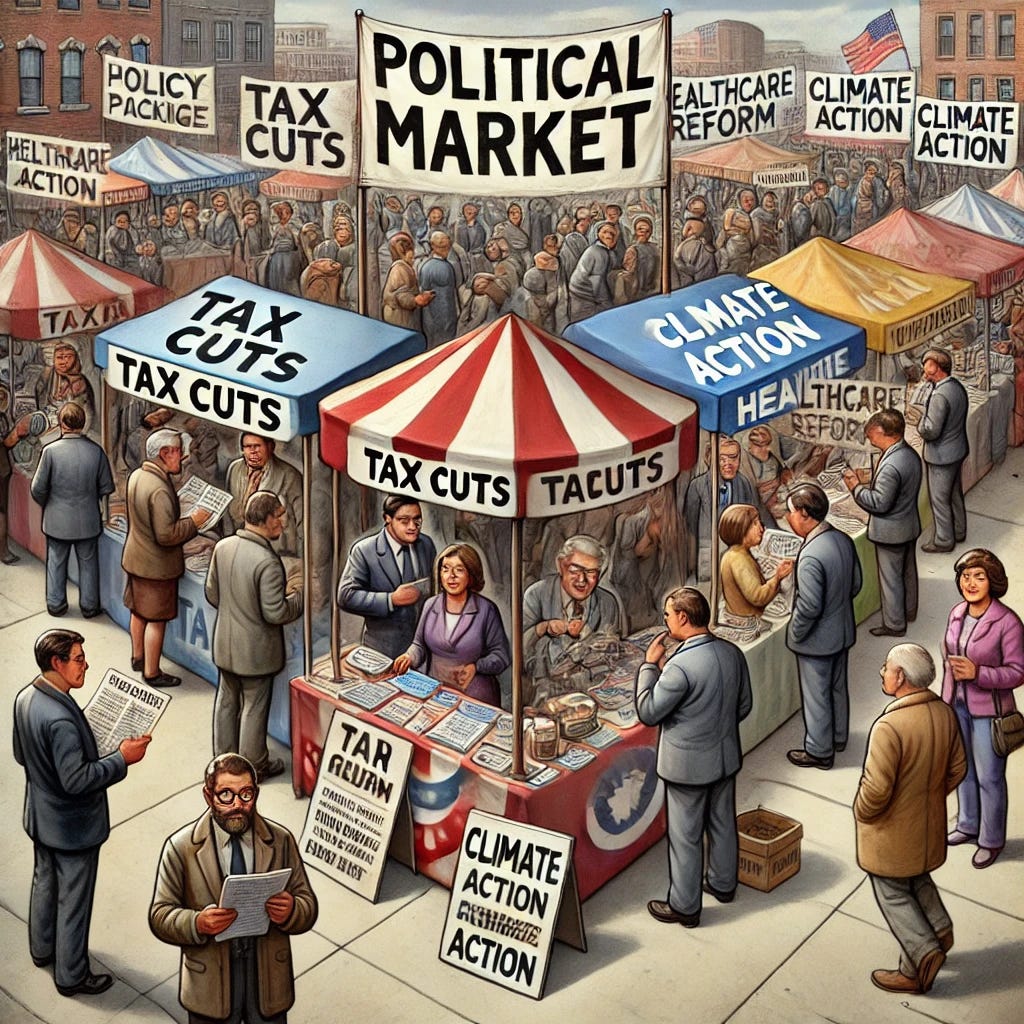

Because of these characteristics, leaders and aspiring leaders have an interest in defending policies that will be in the interest of large sets of people in the domain. We can think of it as a political market, where entrepreneurs offer packages of policies to possible buyers, hoping to find a large group of supporters.

Democracy works for a larger proportion of society than other regimes, not because people find out what is good for society in discussions in the public sphere, but because the political elites have a vested interest in making large swathes of the population happy with their policies.

Democracy also relies on the division of centres of power, with decision-making in different domains and social settings resting in the hands of different people. Political scientist Robert Dahl used the term “polyarchy” to reflect this dispersed nature of power in democracies. Now, it would be naïve to think that this is always for the best. As pointed out by Dahl, there are many things that happen above the awareness of the population, between elites.

Attached to the institutions of polyarchal democracy that help citizens to exercise influence over the conduct and decisions of their government is a nondemocratic process, bargaining among political and bureaucratic elites. - Dahl (1998)

Like in any market, there are imperfections. An important result in economics is that when consumers are uninformed, and when it is costly for them to get informed, firms obtain market power: they can increase the price and decrease the quality compared to the situation where consumers would be perfectly informed. The same mechanisms are bound to happen in politics. With citizens imperfectly informed about the complexities of public policy, there is a possibility for political elites to propose programmes that are not necessarily the best for their coalition—or rather, that are not necessarily best for the least informed members of their coalition, while the most informed subset of the coalition gets a better deal.

But with all their real imperfections, political markets in democracies are better for the large population than those in alternative regimes. Their open nature means that any aspiring leader can seize on a gap between what is currently offered by the political elites and what is actually in the best interests of significant swathes of the population, campaign on it, and gain support. While matters of public policy are complex, citizens do not need to identify on their own which policies are best. Politicians select policies they believe are likely to appeal to voters. Citizens can then judge which of these policies are most likely to align with their own interests.6

In that context, a transparent public sphere, where free speech and institutions of knowledge (science, media) are trustworthy and trusted, is good. It helps citizens identify what is best for them, and therefore constrains the political elite to closely follow their interests. In case of a hiatus, entrepreneurs (politicians, podcasters, bloggers) can seize the opportunity to gain an audience by pointing out the obvious gap for everyone to see once explained.

A well-functioning public sphere can also help facilitate compromises between social groups and their representatives by making available to all the reasons behind different positions and helping participants understand the trade-offs involved (Gutmann and Thompson, 1996). As in any collective setting, talking things through does not necessarily resolve conflicts, but it can help people accept compromises.

We can appreciate why democracy, with such political markets—full of imperfections but with limits to how much elite bargaining can veer away from the broad public interest—is the “worst system except for all the others”. It is here that the ideal vision of democracy is harmful, because it pits actual democratic institutions against an impossible and therefore irrelevant ideal. In doing so, it undermines support for democratic institutions and misleads about what is important in them: the system of balances that ensures the process of social bargaining is taking place, while giving a large number of people a way to make the best decisions for themselves about what should be done in society.

Against guardianship

The failure of idealised visions of democracy to live up to their promises can create a dangerous opening to be leveraged by critics who say what is promised—“power by the people”—is a lie. The critics might then argue that we would be better off throwing all that fake democracy away and placing power in the hands of the right people—either an allegedly good politician or a group of people who would be better at organising society. This is the core of what can be called guardianship: the belief that political decisions should be entrusted to a select few, typically on the basis of superior knowledge, expertise, or alleged virtue.

The insights above give a clear rationale for why this is a terrible solution. Guardianship was famously proposed by Plato, who argued in The Republic that the city should be ruled by philosopher-kings—individuals trained in reason, immune to self-interest, and uniquely capable of grasping the form of the Good. The idea that the most knowledgeable people should be in charge makes sense if the problem of public policy is to identify the public good. But if large parts of politics are about arbitrating between conflicting interests, why would guardians be the best judges? And more importantly, who would ensure that the guardians would not put their own interests above others? Who would guard the guardians?

As the philosopher Karl Popper argued in The Open Society and Its Enemies, Plato’s vision of rule by the best laid the groundwork for authoritarianism: a political system where those in power claim exclusive insight into what is good for all—and suppress dissent in the name of their superior reasons. As the 20th century has amply shown, it is a recipe for collective disaster, with the rulers transforming into an entrenched elite at the top of a regime that primarily ensures that they stay in power, with often very little consideration for the life and death of the people living in the country.

For political institutions to benefit the largest number of people, the ability to decide what should be done in society should rest with a body of members as large as possible. That is the case for democracy: not because voters are wise, but because they are better placed than others to judge what matters to them and to defend it. Any suggestion that decision-making should be delegated to a ruling class—however well-intentioned—opens the door to abuse.

Democracy is commonly described as a system where political power resides in the hands of the people. This abstract definition is often illustrated through the ideal of direct democracy, where enlightened citizens engage in public deliberation to identify and agree on what is best for society. Against this idealised image, actual democratic institutions can easily appear flawed. Citizens are often not highly informed or engaged in matters of public policy, and elites often wield disproportionate influence. Critics of democracy frequently exploit this contrast, using an unattainable ideal to argue for abandoning existing democratic institutions.

A realist view of democratic institutions recognises that their primary function is not to help enlightened citizens identify a single, uniquely correct course of action for society as a whole. Rather, they provide a way to coordinate collective decisions among many possible policy choices, and to manage the distributional tensions these decisions entail. Democratic institutions can be understood as a form of social equilibrium for organising both cooperation and conflict in society. Among the possible political arrangements, democracy is likely to result in better outcomes for most people. It allows the majority of adult citizens to participate in the coalition game that determines who governs. The regular repetition of this game through elections, and the flexibility of winning coalitions, means that most citizens have a chance to be part of the winning coalition at some point—and thus for their interests to be taken seriously by current or aspiring leaders.7

References

Arrow, K.J., 1951. Social choice and individual values. New York: Wiley.

Binmore, K., 2005. Natural justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., Smith, A., Siverson, R. M., & Morrow, J. D. (2003). The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dahl, R.A., 1998. On democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gutmann, A. and Thompson, D., 1996. Democracy and disagreement. Harvard University Press.

Habermas, J., 1974. The public sphere: An encyclopedia article (1964). New German Critique, 3, pp.49–55. Translated by S. Lennox and F. Lennox.

Hayek, F.A., 2001. The road to serfdom. London: Routledge. (First published 1944)

Hobbes, T., 1651. Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common-Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civill. London: Andrew Crooke.

Hume, D., 1739. A Treatise of Human Nature. London: John Noon.

Knight, J., 1992. Institutions and social conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Plato, [c.380 BCE] 2007. The Republic. Translated by D. Lee. 2nd ed. London: Penguin Classics.

Popper, K.R., [1945] 2011. The open society and its enemies. New ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rousseau, J.-J., 1762. The social contract.

Sinclair, U., 1935. I, candidate for governor: and how I got licked. Pasadena: Author.

Rousseau was not entirely naïve about how easy such a will would emerge. He thought that such a will is not guaranteed to exist or to be identifiable at all times. He warned that factions, inequality, and dependence would distort the general will into private interests.

For the economist reader: most interestingly, the public good intuition and its rejection both co-exist in economics. Attentive economics students might legitimately be puzzled by the fact that they are told in some courses that there is no way to aggregate preferences, and in welfare economics courses that we can consider a planner maximising the sum of people’s utilities.

Some other courses introduce the notion of public good by the back door. Is a free trade policy good? Surely there are winners and losers. A free trade policy might benefit the consumers who access cheaper goods but hurt workers in some industries who may lose their jobs and have to find another one. The fact that they are also consumers might not compensate for their losses. So people have conflicting interests on the matter. Faced with that difficulty, an economics course typically introduces the Hicks-Kaldor criterion, which states that if the sum of positive effects (e.g. for the consumers) is larger than the sum of negative effects (e.g. for the workers), then it is good because everybody in society could be made better off with adequate transfers (e.g. a tax on consumers to pay for workers changing jobs). The problem is that whether such transfers are implemented or not, how they would be estimated and paid, and whether they are politically feasible, is left outside of the question.

It is fair to say that this is often akin to economists gaslighting those opposing these “good” reforms. They are in effect saying: this policy hurts you, but it is a public good because, in theory, you could be compensated for your loss with the social benefits of this policy.

In spite of its lack of rigorous foundations, the notion of public good is widely used in politics. Friedrich Hayek wrote about this:

The “social goal,” or “common purpose,” for which society is to be organised is usually vaguely described as the “common good,” the “general welfare,” or the “general interest.” It does not need much reflection to see that these terms have no sufficiently definite meaning to determine a particular course of action. - Hayek (1944)

While I agree with Hayek’s criticism, I do not share his view that market mechanisms are the primary way to organise society. Hayek underestimates the need to have institutions to manage the conflicts of interest in society.

The reason why the notion of the public good is so widely used is likely that competing narratives in distributional conflicts often gain by not being framed in raw bargaining terms such as “We want more,” but instead as allegedly correct solutions from an objective point of view — “It is the right policy.” Farmers don’t ask for subsidies just to raise their income, but also to help them fulfil their role in taking care of natural spaces; people living in an upper-class neighbourhood oppose a new high-rise building to protect the historical style of the area; high-income professionals oppose higher taxes because they claim such taxes have a deflating impact on the economy — and so on.

Note that conflicts of interest are not restricted to raw economic considerations like income and taxes. Many conflicts in society arise from the allocation of status and social recognition, which are major drivers of subjective satisfaction. Indeed, many economic conflicts are actually conflicts over the social apportionment of status and prestige. If wages in a given profession are low relative to other professions, it also signals lower social status for those working in it. Conflicts over pay are therefore often driven by considerations of social recognition.

To the reader interested in economics, the point I make is that among all the possible social equilibria, some are efficient. This means that in such situations there is no possibility of improving the situation of everybody (or at least of some without hurting others). Achieving an efficient outcome instead of a non-efficient one can be seen as a good public decision.

The problem is that there is not one public good that would point to only one efficient equilibrium. There are typically an infinite number of ways of reaping benefits from cooperation and splitting the gains. Should the old be given high pensions to reward them for long years of work? Should the young be given subsidies to give them a push in life? Or perhaps it is the working-age population that deserves more consideration, given that they are shouldering the burden of supporting the old and the young, who are not working.

In Natural Justice, game theorist Ken Binmore uses the framework of repeated games to make this point. In repeated social interactions, there are an infinite number of ways we could decide to ascribe costs (how much everyone needs to spend time and resources) and benefits (who gets the rewards). The efficient equilibria can be represented as the top-right frontier of the set of joint payoffs that can be achieved.

Consider, for instance, a couple, Eve and Adam, who need to do the dishes every day. They both prefer for the dishes to be done, and if they think the other will not do it, they will prefer doing it themselves. There are many ways for them to solve this social problem so that they live in a house with clean dishes (which is better for both). There are an... infinite number of ways for them to achieve efficiency. They could split the task half and half, doing it every other day; Eve could do Monday and Adam all the other days; Adam could do it on days of the month that are prime numbers (2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31) and Eve on the others. They both want to achieve efficiency (the dishes are done), but a key question is how the costs are distributed. This question is equivalent to choosing one of the points on the efficient frontier that sets the exact benefits and costs for each.

For Binmore, fairness norms are the conventions that help us identify one equilibrium among all the efficient ones.

A vision of democracy as aiming to find and implement the public good misses the fact that there are several solutions that are better for all (efficient), and that a key aspect of public debate is bargaining over who gets what.

Political scientist Jack Knight stressed, in Institutions and Social Conflict (1992), that distributional conflicts can even lead to inefficient solutions being implemented because they benefit those in charge. Consider, for instance, the existence of corruption. Autocratic regimes often have more corruption than democracies, possibly because it allows the class of people supporting the regime to enrich themselves and is therefore tolerated by the leadership (Bueno de Mesquita et al., 2003).

Similarly, consumers buying a car don’t have to be car engineers to make reasonable decisions; they can listen to the descriptions provided by different car companies and use this information, along with their personal experience, to make choices likely to match their best interests.

Democracy might not be best for everyone. Some elites, for instance, might expect to fare better under an autocratic regime with a small winning coalition able to extract resources from society.

Really appreciate the clarity here—your framing of democracy as a conflict-resolution tool rather than a truth-finding mechanism is refreshingly grounded. But I wonder if the analysis stops short of the realist critique it sets out to offer.

You describe disagreement as something to be managed, but not as something shaped—by capital, media control, and structural power. What looks like broad consent often hides the fact that key issues (public ownership, taxing wealth, opposition to war crimes) are consistently excluded from the platforms of those with any real chance at power.

If the arena is rigged before the contest begins, isn’t that a bigger democratic illusion than the pursuit of the common good?

Great piece. I think there's another argument for democracy that you didn't directly cover: Democracy, via the broadening of the selectorate, also generates a kind of legitimacy of power that's difficult to challenge on moral grounds. Coupled with robust institutions, this ensures better than any other system stability and peaceful transfer of power. So democracy, even in principle, cannot claim to hand power to the most capable ruler, but it can claim to provide a basis for non-violent change. And that's both better and more realistic than what other systems have in offer.

Like Popper said: the question is not "who should rule", it's "how do we get rid of bad rulers without violence."