Improving the marketplace of ideas: a reasoned defence of freedom of speech

How to make the best ideas win

In three previous posts, I have discussed the good reasons why we form and hold incorrect beliefs. We search not so much for truth, as scientists might, but for arguments, like lawyers, to convince others. We do this as members of groups, whose positions we defend against other groups. This dynamic creates a marketplace of rationalisations where we can shop for ideas or narratives that support the beliefs of our respective groups.

This perspective offers a simple explanation for the now commonly held view that the internet has not led to a public sphere where ideas are exchanged and debates facilitate the creation of an informed public opinion. Instead, there is a concern that the widespread access to digital technologies has led to misinformation and the formation of political echo chambers.

In the next few posts, I’ll discuss solutions to help tackle these issues. In today’s post, I’ll present arguments supporting freedom of speech.

The idea of a marketplace of ideas and its challenges

The view that ideas can compete in a marketplace where the best ones will prevail is often attributed to John Stuart Mill. In his essay On Liberty (1859), he indeed asserts that the freedom to express and hear ideas offers the “opportunity of exchanging error for truth”.1

But the concept of a marketplace does not really originate with Mill. Rather, it was first suggested by the American judge Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes:2

The ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas […] the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market - Holmes (1919)

The premise is that superior ideas—those more aligned with evidence and more logically articulated—may win in an open confrontation with other ideas. However, it's important to note that while better ideas are more likely to prevail in open discussions, this doesn't guarantee they always will. On this point, Mill's perspective deviates from the notion of an efficient market for ideas.3 He stated:

The dictum that truth always triumphs over persecution is one of those pleasant falsehoods which men repeat after one another till they pass into commonplaces, but which all experience refutes [...] It is a piece of idle sentimentality that truth, merely as truth, has any inherent power denied to error of prevailing against the dungeon and the stake. - Mill (1859)

In recent years, it has become widely accepted that truth may not always prevail in the public arena created by digital platforms, where people exchange views, information, and arguments. One commonly accepted explanation is that people are overly gullible and easily deceived by misinformation. In my previous posts, I have presented an alternative explanation: truth does not prevail because our fundamental aim is not to be correct, but to win arguments in social interactions. In this perspective, truth is useful but not essential, and at times, it's inconvenient to the position we defend. This view, developed by Mercier and Sperber (2011), explains a broad range of “biases” in how we engage in intellectual debates, and why it often fails to lead to the emergence of truth.

We can adapt our understanding of the marketplace of ideas with this perspective. The marketplace operates more as a space for rationalisations, where individuals seek not the truth, but arguments and narratives that reinforce their views and interests. However, not all arguments are created equal. Those based on stronger empirical evidence, well-established facts, and logical reasoning have a greater capacity to withstand criticism and win in debates. Thus, even though people in the marketplace of ideas may not be primarily seeking truth, ideas that are closer to the truth are likely to be selected more often because they provide stronger arguments.

The question we then may want to address is: How can we improve the marketplace of ideas to create the right conditions for better ideas to be selected? In the next few posts, I’ll explore three avenues for enhancing the marketplace of ideas from this perspective: freedom of speech, regulating both large private and public content producers, and changing the incentives of content producers.

Freedom of speech: What should be the limits imposed on ideas publicly expressed?

Improving competition: How to help ensure better ideas prevail?

Tweaking the incentives of content producers: Can we improve the incentives of producers to generate better content?

In this post, I look at the first point.

Limiting the barriers to entry

On standard markets, barriers to entry often limit the competition between options. Similarly in the marketplace for ideas, competition can be hindered by barriers that prevent some ideas from effectively competing with established ones.

Government limitations

The primary and obvious source of such barriers to entry are the political rulers who have regulatory powers and may wish to prevent the spread of critical views. As I mentioned in a previous post, newspapers have been frequently banned by rulers in Europe. In 1675, for example, English King Charles II attempted, albeit unsuccessfully, to shut down London’s coffee houses, claiming they had “produced very evil and dangerous effects.”

Nowadays, autocratic governments, such as China and Russia, censor critical views and harshly punish opponents, with penalties ranging from imprisonment to death. In Western democracies, governments generally possess less power to sanction critics, and opposition media are often widely read. In their book Spin Dictators, Sergei Guriev and Daniel Treisman (2022) illustrate how a range of states, formally presenting themselves as democracies, implement various barriers to entry against opposing views, effectively silencing most criticism in the public sphere. The recent case of Hungary demonstrates how freedom of the press can be subtly eroded by a democratically elected government, leading to a gradual shift towards autocratic rule.

From this viewpoint, democracy is more likely to remain resilient if citizens and civil society remain vigilant in preventing the government from limiting critical speech, either through direct or indirect sanctions. These sanctions can include legal proceedings, or exerting influence on individuals' careers and financial situations.

Social pressure

However, political rules are not the only threat to the marketplace of ideas. John Stuart Mill foresaw that social pressure could also erect significant barriers, preventing certain views from being expressed:

[Society] practices a social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression, since, though not usually upheld by such extreme penalties, it leaves fewer means of escape, penetrating much more deeply into the details of life, and enslaving the soul itself. Protection, therefore, against the tyranny of the magistrate is not enough; there needs protection also against the tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling, against the tendency of society to impose, by other means than civil penalties, its own ideas and practices as rules of conduct on those who dissent from them - Mill (1859)

The risk of social pressure playing a role in public debate is enhanced by our tendency to prioritise winning arguments over finding the truth. Accusing our opponents of holding unacceptable views and seeking to draw social disapprobation upon them is a strategy we are likely overly drawn to. An illustration of this tendency is the ironically coined Godwin’s Law, which emerged from early internet discussions: “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1”.

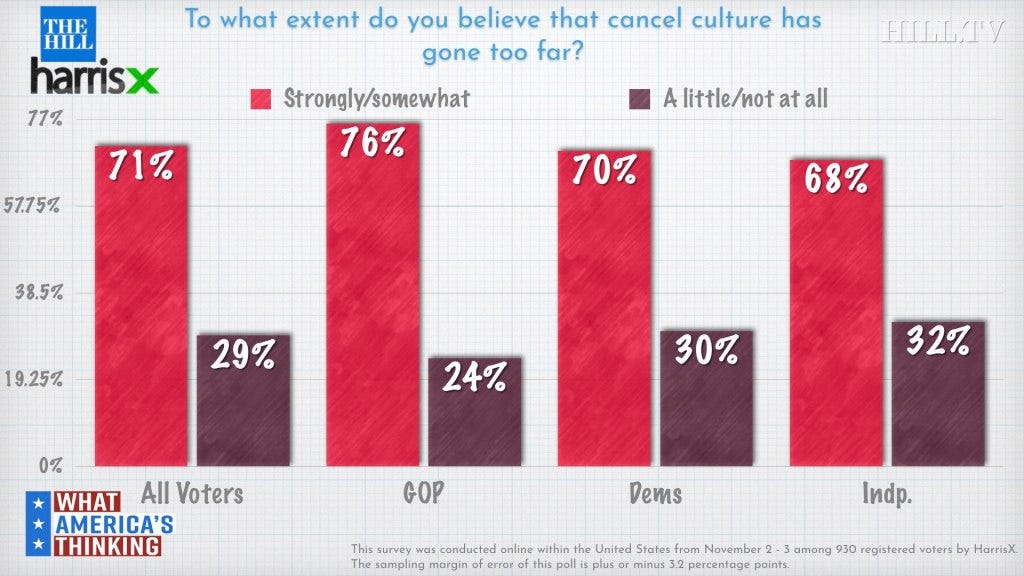

Mill’s concern about social sanctions is particularly pertinent to the debate about free speech, especially in light of recent discussions on cancel culture. Numerous individuals have been deplatformed (expelled from public platforms) or even lost their jobs due to positions they have taken in the public sphere.

Some have denied the existence of these cancellations or minimised their impact. However, evidence indicates that collective actions leading to such sanctions have occurred a substantial number of times (link). Furthermore, evidence also suggests that these actions can significantly affect the reach of the targeted views.4

The main effect of cancellations is likely one that remains unseen. A few highly publicised cancellations can exert a significant deterrent effect.5 This phenomenon was pointed out by Glenn Loury in an excellent article on self-censorship, written 30 years ago:

For every act of aberrant speech seen to be punished by “thought police,” there are countless other critical arguments, dissents from received truth, unpleasant factual reports, or non-conformist deviations of thought which go unexpressed, or whose expression is distorted, because potential speakers rightly fear the consequences of a candid exposition of their views. - Loury (1994)

Freedom of speech and its justifications

In response to cancel culture, numerous intellectuals have defended the principle of freedom of speech, advocating that everything should be open to discussion. This stance has historically been championed with conviction by Noam Chomsky.

Critics of absolute freedom of speech answer that speech can be “harmful” and that limits are inevitable. Indeed, even staunch defenders of freedom of speech, like Chomsky, concede that there should be boundaries. For example, public speech can be used to incite violence. It is reasonable for even a highly liberal society to impose certain limits on speech.

The key difficulty lies in pinpointing where to set this limit. It's reasonable to ban calls to violence, but the situation becomes murkier with insults or statements that might not be overtly offensive but could be perceived as such. The complexities of these issues are not just theoretical puzzles for philosophy majors pondering university essays. Several cases of cancellation have pushed the limits of unacceptable speech far away from clear-cut “harm”. In an extreme example, a university professor, Greg Patton was sanctioned by his university not for what he said—a Chinese word—but for the fact that it could sound like a racial slur in English.

Instead of increasing the limits on speech, there are good reasons to be bullish towards freedom of speech.

The unintended cost of overprotection

While initially well-intentioned, these overreaches in speech restriction carry significant costs. To start with, overprotection may ultimately not benefit those it aims to shield. In their book The Coddling of the American Mind, Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff (2018) point out that the culture of safetyism may result in intellectually bubble-wrapping new generations, rather than preparing them to confront uncomfortable ideas. This approach could lead to worse psychological outcomes in the long term.

The risk of being overconfident in our views

Calls to ban some views from public discourse might seem justified if the aim is to dominate the battle over public narratives. However, if the goal is to ascertain what is right, we may want to be careful and cultivate epistemic humility—that is, the recognition that our views could be mistaken. Allowing the expression of ideas we consider erroneous offers us an opportunity to reconsider our stance. Additionally, engaging with and understanding opposing ideas can bring greater clarity to our own. These insights were also articulated by John Stuart Mill:

The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth; if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth produced by its collision with error. - Mill (1859)

The risk of lowering the trust in knowledge institutions

A by-product of a free marketplace of ideas is the increased confidence we can place in ideas produced by mainstream knowledge institutions (e.g mainstream media, science). These ideas are more credible if we know they have withstood the test of critical scrutiny and emerged on top. Conversely, if we are aware that the only ideas being publicly conveyed were shielded from criticism, we may be less convinced of their intrinsic quality. Michael Muthukrishna articulates this point in his book A Theory of Everyone (2023) when examining the difficult questions faced by scientists when biological explanations intersect with issues about social inequality. He notes that even honest and fair researchers may hesitate to speak out if they risk “career-destroying accusations” for discussing ideas and findings outside a narrowly defined acceptable discourse. This leads to a potential loss of public trust in scientists, as they may be perceived as overly committed to certain conclusions. He rightfully concludes, “if you can’t trust scientists to be careful, open, and honest, you can’t trust science”.

The difficulty of delegating the control of content

Some part of social control over speech is ensured by content moderators who act as guardians of public discourse. But this raises the classic question: who will guard the guardians? How can we ensure that those overseeing public discourse will enforce limitations in the interest of truth and the promotion of better ideas, rather than for other purposes?

There is, in particular, a risk of undemocratic elitism. Consider a scenario where the public favours ideas that the guardians deem unacceptable. To what extent should they have the authority to decide what views people can access? Asking this question doesn't imply there shouldn't be guardians. Rather, it underscores the need for checks and balances, especially as their influence over aspects of social life grows.

Here again, it's not just a theoretical question. A clear example is provided by “fact checking” organisations that have emerged to combat misinformation and often guide online platform content moderation. In several instances, these organisations have been criticised for exhibiting a partisan bias in their definition of “misinformation”. In a discussion of this issue, Dan Williams highlighted the challenge of entrusting certain individuals with the authority to determine what to exclude from the public sphere as “false”:

Judging what constitutes misleading communication in this extremely broad sense is a highly subjective affair, easily swayed by biases, interests, pre-existing prejudices, and values of myriad forms. - Dan Williams

The undermining of the rules of a liberal public sphere

Finally, the implementation of stringent rules to exclude certain ideas from the public sphere can negatively impact how the public sphere itself functions.

Firstly, the exclusion of a range of ideas on the grounds of undesirability can reduce the public's ability to engage and discuss challenging topics. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that norms of speech can be strategically employed to label opposing viewpoints as harmful. Consequently, speakers are pressured not only to refrain from expressing these ideas but also to avoid even the risk of appearing to hint at them in their discourse.

A generic problem with conventions of values-signalling is the ease with which they can be abused by partisan opportunists . When listeners are keen to discern a speaker's basic values on a crucial issue, a speaker has to worry that his political enemies will, by distorting or misrepresenting his expressions, falsely depict him as being morally unsound. He has to take care, in other words, not to be smeared . To minimize this risk the speaker may need to avoid some issues altogether, or to speak only in the most circumspect and indirect way, especially if he is criticizing the consensus view. Pointed remarks on a sensitive topic lend themselves to caricature and distortion. Thus, and again ironically, the public's heightened moral sensitivity together with a political climate of intense partisan conflict may actually result in a lower level of effective moral discourse, as the making of nuanced arguments and the drawing of fine distinctions become too risky for political speakers. - Loury (1994)

Secondly, cancelling speech we disagree with undermines the principles of tolerance that benefit everyone, including ourselves. Who can guarantee that we will always be those holding the censoring power? The case of Michael Eisen, who initially downplayed the risks of cancellations, only to lose his editorial position due to a public political stance, serves as a stark illustration of this point.

In conclusion, my reasoned defence of free speech urges caution against our instinct to “win” political arguments by excluding ideas we find unpalatable. To have a marketplace of ideas as a mechanism for elevating the best ideas in society, we need to resist the appeal of shaping it around our positions.6 As Glenn Loury recently stated:

A commitment to a liberal political order involves taking risks, including the chance that speech we abhor may go unrefuted. - Glenn Loury

References

Coase, R.H., 1974. The market for goods and the market for ideas. The American Economic Review, 64(2), pp.384-391.

Gordon, J., 1997. John Stuart Mill and the" Marketplace of Ideas". Social theory and practice, 23(2), pp.235-249.

Guriev, S. and Treisman, D., 2022. Spin dictators: The changing face of tyranny in the 21st century. Princeton University Press.

Haidt, J. and Lukianoff, G., 2018. The coddling of the American mind: How good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure. Penguin UK.

Loury, G.C., 1994. Self-censorship in public discourse: A theory of “political correctness” and related phenomena. Rationality and Society, 6(4), pp.428-461.

Marshall, W.P., 2021. The truth justification for freedom of speech. in Stone, A. and Schauer, F. eds., The Oxford Handbook of Freedom of Speech. Oxford University Press.

Mercier, H. and Sperber, D., 2011. Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34(2), pp.57-74.

Mill, J.S., 1859. On liberty and other essays.

Muthukrishna, M., 2023. A Theory of Everyone: The New Science of Who We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We’re Going. MIT Press.

Mill's thinking was influenced by the writings of John Milton, who, in 1644 wrote in Areopagitica for the liberty of unlicensed printing.

Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties […] "Let [truth] and falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter. - Milton (1644)

Similarly, the economist Ronald Coase, who embraced the concept of a market for ideas, emphasised that such a market is likely to be characterised by significant “market failures”:

My argument is that we should use the same approach for all markets when deciding on public policy. In fact, if we do this and use for the market for ideas the same approach which has commended itself to economists for the market for goods, it is apparent that the case for government intervention in the market for ideas is much stronger than it is, in general, in the market for goods. […] it is easy to see that in practice there is likely to be a good deal of “market failure”- Coase (1974)

Another interesting example is this study on Reddit forums:

However, we should not overestimate the impact of this effect. The containment of certain ideas through cancellation and deplatforming is likely to be most effective on minority ideas with limited appeal. In contrast, for ideas that resonate with a broad audience, being cancelled on one platform may simply lead to the creation of alternative platforms catering to the demand for these ideas. Consequently, the strategy of containment through cancellation might paradoxically be least effective against the very ideas most likely to gain widespread traction—and hence pose the greatest risk from the censor’s perspective.

A basic principle from game theory states that, in equilibrium, if the punishment for norm violation is extremely severe, violations seldom occur because everyone complies. Consequently, the actual instances of punishment may be almost non-existent, yet the risk of punishment exerts a significant influence on behaviour.

I am only discussing the value of free speech to make the best ideas emerge in public discourse. The debate on free speech goes beyond this specific point, with some arguing that it is a requirement for individual dignity (Marshall 2021). This perspective raises interesting questions beyond the scope of this post (I will likely revisit it when discussing social games of communication in later posts).

I enjoyed your book. You wrote above that "ideas that are closer to the truth are likely to be selected more often because they provide stronger arguments." The humoral theory of disease may have survived for many centuries not because it was closer to the truth or provided stronger arguments but that it could be adapted and adopted by healers of various religious traditions. A virus-like model might illustrate the development, survival and spread of ideas.

Interesting discussion, thank you! (Not just this post but previous ones too. In particular, your write up of the marketplace of rationalisations was very clear and helped me see that idea fresh again.)

Now you're turning to solutions, I'd like to make the case for radically open approaches to governance, and specifically far greater use of citizen assemblies. Their deliberative format goes with the grain of human reason as a tool of argumentation. This in turn makes them a good "mechanism for elevating the best ideas in society". And because they do not entail the grubby compromises of representative democracy, participants in a citizen assembly can more easily meet your key demand, to "resist the appeal of shaping it [debate] around our positions".

My paper on the topic is 'Human nature & the open society'. I'd love to hear any thoughts you have!

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/64e385e145e8e55034c9cdc3/t/64e6019ca2870010b4a3e56c/1692795293057/Scott-Phillips+2023+Human+nature+%26+open+society.pdf

It's part of an edited collection, 'Open Society Unresolved'.