The amazing layers of strategic thinking behind our everyday conversations

And how hidden principles of cooperation shape our conversations

One of the points I made in Optimally Irrational is how incredibly good we are at solving the complex problems we face in our lives. We are often oblivious to the feats we are achieving. There is hardly a better example than something we do every day: talking to each other.

The Moravec paradox is that while computers are extremely good at tasks humans find hard, like making complex calculations, they have struggled with tasks that humans find almost trivially easy like vision, perception and language. Stephen Pinker made this point in The Language Instinct, thirty years ago:

The main lesson of thirty-five years of AI research is that the hard problems are easy and the easy problems are hard. The mental abilities of a four-year-old that we take for granted—recognizing a face, lifting a pencil, walking across a room, answering a question—in fact solve some of the hardest engineering problems ever conceived. - Pinker (1994)

In this post, I will look at the simple acts of talking with other people. Because we navigate these situations mostly effortlessly, we can be oblivious to the cognitive feats we achieve in what appear to us as “simple interactions”. In fact, the fabric of our everyday communications is woven with fundamental principles of cooperation that require layers of strategic considerations.

Deep cooperation in our simple discussions

I have explained before how communication is a key aspect of human sociality that relies on cooperation. Information is valuable and from our repeated interactions we can gain from mutually exchanging valuable information: I give you some valuable information today, and you’ll give me some tomorrow. Going beyond this observation, one of the fundamental ideas that emerged from the field of pragmatics—the study of how we use language in practice—is that cooperation fundamentally shapes how we communicate. It influences what we say and how we say it.1

Grice’s Cooperative Principle

There are plenty of ways to convey a given idea or piece of information. How should we choose the words we use? The philosopher Paul Grice famously suggested that we should aim to be as cooperative as possible, a principle he called the Cooperative Principle:

Make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged. One might label this the Cooperative Principle. - Grice (1967/1989)

This principle is written in a way that echoes Kant’s moral categorical imperative,2 but Grice does not see it as a moral principle. He only meant for it to be “a rough general principle which participants will be expected (ceteris paribus) to observe.” Grice’s idea is that people should follow this principle if the “purpose [of a discussion is] a maximally effective exchange of information”.

Grice gives additional content to the idea of what “required” means in the cooperative principle with specific rules, “maxims”. For instance, Grice’s maxim of quantity states a contribution should be “as informative as required” for the purpose of the exchange, but no more. Another of Grice’s maxims the maxim of quality, states that a contribution should not claim something false, nor should it claim something for which it lacks evidence.

Grice’s idea is not only that these principles should be followed in everyday discussions, but also that we most often spontaneously follow them. It is when these rules are violated that we can appreciate they were there in the background.

Examples of violation

Examples of violations of Grice’s principles are easy to find. Consider the maxim of quantity. Not saying enough in a discussion will typically leave others hanging on your words, wondering why you did not say more. It is often used for comic effect when somebody provides a literally correct answer, that falls short of the type of answer expected in the discussion. Consider situations where somebody asks a question that is meant implicitly as a request for information: “Do you know where the toilet is?” Replying “Yes, I do” is correct but seems wrong as an answer. It feels so because it violates the maxim of quantity: it provides too little information given what is expected in this context.

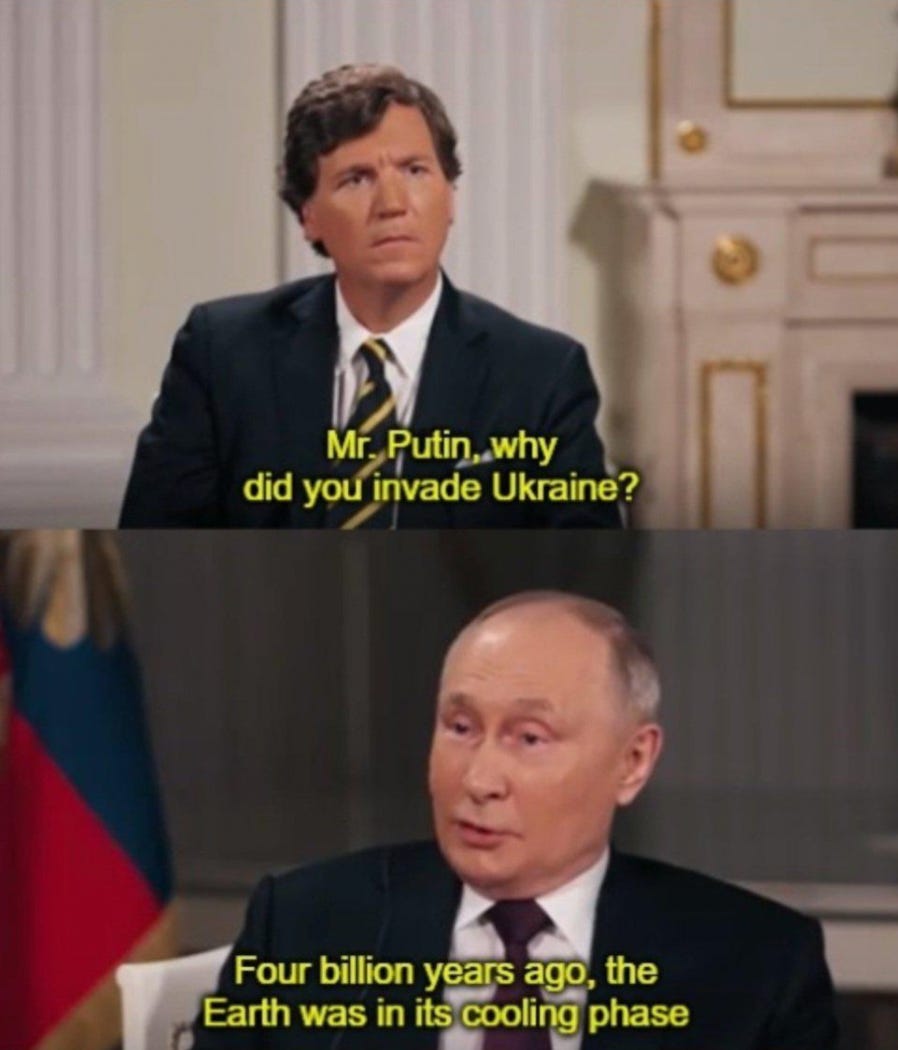

The opposite violation of the maxim of quantity is when somebody gives you too much information. This violation is sometimes characterised as “rambling”. The news cycle recently provided us with a good example when Tucker Carlson asked Vladimir Putin an introductory question about the context of his decision to invade Ukraine, Putin asked for 30 seconds to 1 minute to give Carlson “a short reference to history”. He then went on a 30-minute monologue on Russian history starting in 862. This answer became a meme as a breach of the reasonable expectation about the length of an answer. It was simply a vastly disproportionately long answer to Carlson’s question.

Relevance principle

But Grice’s principles of cooperation still leave “what is required” not fully defined. How much should be said and how much is too much? Dan Sperber, a cognitive scientist, and Deirdre Wilson, a linguist, proposed one of the most interesting extensions to Grice’s approach: relevance theory. In their 1986 book Relevance, they propose that what people aim to do in communication is to maximise relevance which they define as the useful effects of information on the listener’s beliefs, minus the cost of processing this information. In that perspective, a statement is all the more relevant if you learn something from it without having to spend too much time processing it.

With this criterion, it is possible to redefine Grice’s cooperative principle as the common understanding that people should aim to maximise the relevance of their statements when they discuss with each other. Sperber and Wilson proposed that a single principle allows us to understand how people cooperate when they talk to each other: the Principle of Relevance:

Every act of ostensive communication conveys a presumption of its own optimal relevance. - Sperber and Wilson (1986)

This principle recovers the different insights from Grice’s maxims. For instance, consider the violation of the maxim of quantity in the previous examples. If somebody asks “Do you know where the toilet is” and you answer “Yes, I do”, you are not giving enough information in the following sense: it is not enough, given that you could have provided more information (e.g. “at the end of the corridor, on the right”) that would have benefited the listener by changing his/her beliefs at minimal cost. Your answer failed to be optimally relevant. On the other hand, when Putin gave a 30-minute history lecture to Tucker Carlson, it was too much information in the sense, that he could have informed Carlson about the reasons for his actions in a much more economical way.3

But the Principle of Relevance has another implication. Because we have a common understanding that this principle is followed in a discussion, it helps us interpret statements that could have a wide range of interpretations. Let’s consider a simple example taken from Wilson and Sperber (2012):

PETER: Do you want to go to the cinema?

MARY: I am tired.

This interaction is easy to understand. Mary declined Peter’s suggestion. But the fact that we understand Mary’s answer intuitively may prevent us from appreciating the subtlety of what happens in this interaction. Think about it, taken literally, Mary’s answer is not answering Peter’s question. She simply states how she feels.

Telling Peter how she feels is not necessarily a good answer. If she had said “I am thirsty” or “I am sad”, her answer would be somewhat odd and hard to understand. So how can Peter easily understand Mary’s meaning when she answers “I am tired”?

The Principle of Relevance provides a simple answer: given that Peter and Mary have a shared understanding that Mary should aim to utter an optimally relevant statement, Peter can look for the interpretation that is optimally relevant. In short, Peter can think “If Mary said she is tired, it must be relevant given my question.” Peter and Mary share common expectations, like the fact that a person who is tired may be unwilling to engage in some activities. Peter can then conclude that, with her answer, Mary must imply that she is too tired to be willing to go to the cinema. She is therefore declining Peter’s suggestion and providing a reasonable cause for her decision. Mary could have provided the same information with the statement: “I am too tired today to go out. I do not wish to go to the cinema.” The principle of relevance allows Mary to convey the same information in only three words.

The principle of relevance is violated either when a speaker does not choose the most relevant statement—like the violation of Grice’s maxim of quantity—or when a listener does not choose the most relevant interpretation of a statement given the context. This point is often used for comic effect when a statement is interpreted literally in a way that is obviously not in line with the expected interpretation.

The game theory of cooperation in communication

Social norms, solutions to repeated games

Grice’s cooperative principles and Sperber and Wilson’s relevance principle make sense in the general view of social norms as equilibria of social games. That is, they are rules that allow cooperation to be sustained over time and benefit all.

Grice did not venture explicitly into considerations about norms and game theoretical concepts. But his perspective is amenable to such an interpretation. He described the act of “talking as a special case or variety of purposive, indeed rational, behavior”. To him, the cooperative principle had a quasi-contractual nature.

I would like to be able to think of the standard type of conversational practice not merely as something that all or most do in fact follow but as something that it is reasonable for us to follow, that we should not abandon. For a time, I was attracted by the idea that observance of the Cooperative Principle and the maxims, in a talk exchange, could be thought of as a quasi-contractual matter, with parallels outside the realm of discourse. - Grice (1967/1989)

This is indeed what it would be if we conceive Grice’s cooperative principles, and Sperber and Wilson's relevance principle, as equilibria of repeated communication games.4 That is, they are rules that all participants have an interest in following. By fostering cooperative behaviour in communication, they benefit all. But as equilibria of games, they are (by definition) self-enforcing. Participants in a discussion have an interest in respecting these rules. Violating them is associated with costs: losing the trust and esteem of others as a valuable speaker.

During a discussion, violations can attract direct reprimands from others starting with simple mockery or signals of annoyance to open criticism. Failing to pick up on these early signs may lead others to stop the discussion early. After the discussion, word can spread about your poor understanding or respect for the norms of discussion and negatively impact your reputation. Instead of being described as insightful and rigorous, people may instead describe you as boring or sloppy. It may make the difference between you being seen as a desirable interlocutor for future discussions or not.

Higher levels of mindreading

The relevance principle has another implication. For it to guide our discussion,5 it requires speakers and listeners to engage in surprisingly subtle levels of mindreading. Consider the exchange between Peter and Mary above. For Peter to understand Mary, he needs to believe that she intends for her statement to be interpreted by Peter as relevant. Hence, Peter needs to think that Mary expects Peter to anticipate Mary will try to make a relevant statement. These beliefs about beliefs are called higher-order beliefs and a simple utterance like “I am tired” and its correct interpretation by Peter will routinely require at least third-order beliefs.6

Behavioural economists and psychologists tend to find that people do not go above third-order beliefs in experiments as it gets harder and harder to form higher-order beliefs. However, the results of psychological experiments, where people engage in abstract, and often unusual, mindreading tasks may be misleading. Cognitive scientist Thom Scott-Phillips suggests in his book Speaking our Minds that we are uncannily good at manipulating higher-order beliefs in our commonly experienced communication exchanges.

Recursive mindreading is not cognitively demanding. More likely, it is, like simple mindreading, something that we do habitually and subconsciously, as part of our everyday, low-level perception of the world around us. - Scott-Phillips (2014)

This idea can be illustrated by a simple scenario initially discussed by Sperber (2000). Let’s consider a situation where Mary eats berries in front of Peter with an expression indicating to him that they are good.

The meaning of Mary’s behaviour is easy to understand for Peter: Mary is letting him know that the berries are good. However, this simple act of communication involved several levels of mindreading. Not only is Mary letting Peter know that she likes the berries, but she is also letting him know that she wants to let him know that fact. When analysing this example, Sperber sees up to five higher-order beliefs being required for both Peter and Mary to have a full understanding of the situation.

Recursive mindreading is important because it allows participants in a discussion to reach a common understanding of their intention to communicate. This common understanding, in turn, can then help them coordinate on interpretations of the statements they make using the Principle of Relevance.

This perspective casts light on the high cognitive abilities required for our daily discussions to work. The psychologist Michael Tomasello surmised that our unique ability to communicate via language emerged naturally from our higher cognitive abilities allowing us to cooperate in repeated interaction and engage in recursive mindreading.

The combination of helpfulness and recursive mindreading led to mutual expectations of helpfulness and the Gricean communicative intention as a guide to relevance inferences, which could then come under social norms created by still another uniquely human propensity, in this case to be like and to be liked by others in this social group. - Tomasello (2008)

It explains why humans are the only animals able to speak. Our closest ape cousins, for instance, fall short of our recursive mindreading ability.

The results of behavioural science are often presented as pointing to human cognitive limitations. Against this view, the study of the most mundane social interactions, everyday discussions, shows that they involve an incredibly high degree of cognitive sophistication and mindreading ability. It explains why, until recently, computers have been extremely poor at engaging in discursive interactions with us (e.g. the frustrating experience of chatbots). What seems easy to us is actually surprisingly hard when you don’t have a human brain.

This is a post in a series of posts on communication games. In the next post I will discuss how these insights help us understand the limitations of large language models like ChatGPT that make them sound not really human.

Previous posts related:

Game theory - an introduction

Social norms as equilibria of social games - What social norms are: solutions to cooperate in repeated interactions

The importance of a good reputation - What “reputation” is and why it matters in repeated interactions

How caring for our reputation shapes our lives - How we manage our reputation

Communication games - The games we play when we communicate

References

Dekel, E. and Siniscalchi, M., 2015. Epistemic game theory. In Handbook of game theory with economic applications (Vol. 4, pp. 619-702). Elsevier.

Franke, M., 2009. Signal to act: Game theory in pragmatics. University of Amsterdam.

Grice, P., 1989. Studies in the Way of Words. Harvard University Press.

Pinker, S., 1994. The language instinct: How the mind creates language. Penguin UK.

Scott-Phillips, T., 2014. Speaking our minds: Why human communication is different, and how language evolved to make it special. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Sperber, D., 2000. Metarepresentations in an evolutionary perspective. Metarepresentations: A multidisciplinary perspective, 10, pp.117-137.'

Sperber, D. and Wilson, D., 1986. Relevance: Communication and cognition (Vol. 142). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tomasello, M., 2008. Origins of human communication. MIT Press.

Wilson, D. and Sperber, D., 2012. Meaning and relevance. Cambridge University Press.

Yus, F., 2023. Relevance Theory, Humour and Internet Communication. In Pragmatics of Internet Humour (pp. 9-58). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

You may rightfully ask about situations where communication is not cooperative. What about quarrels? What about situations when people tread carefully and avoid saying exactly what they think? This is for a future post.

“Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end.” - Kant

While every minute of Putin’s statement may have contained some information, he may have been able to provide Carlson with a general understanding of his position in a few minutes. After that even though every additional minute might have been informative, the additional gain in information may not be worth the cost in terms of attention and time.

For game theorists readers: My game-theoretic interpretation of Grice and Sperber and Wilson’s principles is based on seeing them as equilibria of repeated games of communication where principles of cooperation can benefit all. This perspective is somewhat different from the, otherwise interesting, application of the game theory of one-shot interactions to recover some of the ideas from Grice and the area of pragmatics. See, for instance, Franke’s book Signal to Act: Game Theory in Pragmatics (2009).

Thom Scott-Phillips has a Substack. I recommend it.

Peter thinks (Level 3) that Mary expects (Level 2) that Peter anticipates (Level 1) that Mary will say something relevant. Economist readers can find an introduction to the formal treatment of such beliefs in Dekel and Siniscalchi (2015).

A lovely post. Has relevance theory been applied to rhetoric?

Extremely useful and ... relevant. Lots of useful info packed into a compact, clear package!