How caring for our reputation shapes our lives

The psychology and game theory of reputation management

In my previous post, I described what reputation is: the belief others have about our intrinsic qualities. Here I discuss how this simple understanding explains how reputation management shapes our psychology and our social interactions in a wide range of ways.

In Othello, Shakespeare gave us one of the most famous examples of somebody caring greatly about their reputation. Lamenting his demotion from the position of lieutenant and the loss of his reputation, Cassio states: “I have lost the immortal part of myself, and what remains is bestial.”

The philosopher Gloria Origgi gives us a way to understand Cassio's concern. In her book Reputation (2018), she describes reputation as a “second self that guides our actions, sometimes even our interests.” Consequently, reputation management is a key element shaping our social interactions: we take great care in building, maintaining, and preserving this social self. Understanding reputation and its role can help us lift a veil on many aspects of our lives that may initially seem strange or hard to fathom.

The psychology of reputation management

Reputation is valuable not just symbolically, but also practically. A good reputation helps you gain the trust of others and convince them to cooperate with you, work with you, and side with you. It is therefore normal for us to care greatly about our reputation, as it embodies the reality of our future social prospects.

The importance of our reputation helps explain why we are endowed with pride, shame, and guilt. These self-conscious emotions help us appreciate the implications of our actions on our reputation. They can be seen as subjective values reflecting the actualised benefits or costs of our actions, given how they relate to our reputation (Frank, 1988). In Laws, Plato describes shame, for instance, in these terms:

There is the fear of an evil reputation; we are afraid of being thought evil, because we do or say some dishonourable thing, which fear we and all men term shame. - Plato

The feelings of pride and shame can be seen as reflecting the shadow benefits and costs, respectively, of our actions observed in public. A positive action or outcome witnessed by others elevates our reputation, and pride can be conceived as the emotional gauge measuring this impact. Conversely, shame serves a symmetric function for negative actions or outcomes that are publicly observed.1

You may wonder “what about guilt then?” Guilt is experienced even when disreputable behaviour remains unobserved (Smith et al., 2002). Psychologist David Ausubel (1955) defined guilt as “a special kind of negative evaluation which occurs when an individual acknowledges that his behavior is at variance with a given moral value to which he feels obligated to conform.”

Guilt therefore seems to induce an intrinsic motivation to behave well. It differs from shame, which reflects the external costs of a loss of reputation. From an evolutionary perspective, such intrinsic motivation can serve two functions. First, experiencing an intrinsic cost can have a purpose: to reflect the risk of future negative reputational costs associated with any bad action.2 This idea was proposed by the biologist Robert Trivers:

It is possible that the common psychological assumption that one feels guilt even when one behaves badly in private is based on the fact that many transgressions are likely to become public knowledge. - Trivers (1971)

Our actions are rarely fully outside of others’ purview. Some people could have seen us, some may learn about it, and some may then talk about it. Guilt can help us take into account this risk, even when there is no immediate audience to whatever we are doing.3

Second, in situations where we have been found doing something wrong, experiencing and displaying guilt can help mend our reputation.4 Visible signs of guilt serve as a signal of our intrinsic motivation to behave well, thereby helping to rebuild trust and reaffirm our value as social partners.5

Notably, caring about our reputation requires some advanced cognitive skills. If reputation is others' beliefs about us, caring about our reputation and what can impact it requires forming beliefs about others' beliefs (second-order beliefs).6 Reputation management is, for that reason, something uniquely human. It is observed to arise early in human children but not in chimpanzees, whose mind-reading abilities are much less developed (Engelmann et al., 2012).

A common trope about human behaviour is that human emotions conflict with rationality. Contrary to this view, emotions like pride, shame, and guilt credibly reflect an implicit accounting system that tracks the influence of our actions on our reputation and, consequently, on our social prospects. In doing so, they help us make better decisions, appreciate when we make mistakes, and try to make up for them. These emotions make us better at navigating the complex web of social interactions.

The management of our reputations shapes our interactions

Concerns for reputation generate honest behaviour

Because good actions lead to a good reputation, the care for our reputation motivates us to behave well towards others. However, this predicts that it should be the case primarily when we expect long-term interactions, that is, when losing reputation is the most costly. In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith discusses this consideration about reputation:

When a person makes perhaps 20 contracts in a day, he cannot gain so much by endeavouring to impose on his neighbours, as the very appearance of a cheat would make him lose. Where people seldom deal with one another, we find that they are somewhat disposed to cheat, because they can gain more by a smart trick than they can lose by the injury which it does their character. - Smith (1776)

This insight from Adam Smith explains why it is reasonably safe to trust the companies you interact with regularly. For instance, when you buy something at your supermarket, you can safely assume that you’ll get what you expected when you open the packaging at home. If ever what’s inside is not what you were expecting (e.g., unsatisfactory quality), you can usually get reimbursed.7

It would be wrong, though, to think that people only behave well with the direct intention of improving their reputation. Instead, our self-conscious emotions often give us proximate motives: we want to feel pride and avoid shame and guilt. In turn, people who show signs of experiencing these emotions get a better reputation as potential social partners. We appreciate people who show pride in their work, but avoid people who are shameless or conscienceless and do not seem to experience guilt.

Reputational information represents a large share of our discussions

In my previous post, I explained how game theory models represent reputation as a reflection of what we have done in the past. These models often treat the record of our past actions as public: everyone can observe it, even if imperfectly. But in reality, reputation is much more complex. We don't just rely on what we see people doing. We also use language to share and collect information about others through our conversations. According to Dunbar's research on human discussions, around two-thirds of it is about social gossip, whereby we learn what others have done, why, and how (Dunbar, 2004).

When we witness someone's actions, it's usually in interactions involving just a small group of people. As a result, only a few can directly observe whether others are following or breaking the social norms of cooperation. However, this information is valuable, beyond this small circle, as it is relevant to anyone who may interact with people from the same group in the future.

Gossip—the social exchange of information about the deeds of others—is therefore mutually beneficial. Dunbar compares it to mutual grooming in primate groups: a way to strengthen social bonds through a network of small, kind gestures. Gossip also has another effect: it makes our private dealings less private. When we know that our actions might become the subject of gossip, it reinforces our incentive to behave well, even when we think no one is watching (Feinberg et al., 2014).

Because gossip can influence others' reputations, it can also be used strategically to damage the reputation of competitors or enemies (Fonseca and Peters, 2018). In other words, people can purposefully paint others in a bad light behind their back. As a result, negative gossip may always be met with some scepticism about the gossiper's true motives: is it genuine information or slander?

How, then, can gossip lead to fairly accurate reputations? The answer lies in the fact that reputation also operates in the domain of gossip. Gossiping interactions are cooperative, so they too build a reputation: Is the information somebody spreads truthful and useful, or dubious and false? A gossiper caught spreading inaccurate information about another person will suffer consequences to their reputation for credibility and trustworthiness. Therefore, people seem to tread carefully when engaging in negative gossip. Critical information is presented with careful qualifiers about the degree of certainty (“I think”, “it seems”, “I have been told”) to reduce the gossiper's responsibility if the information is later proven false.

Why a three-strikes rule

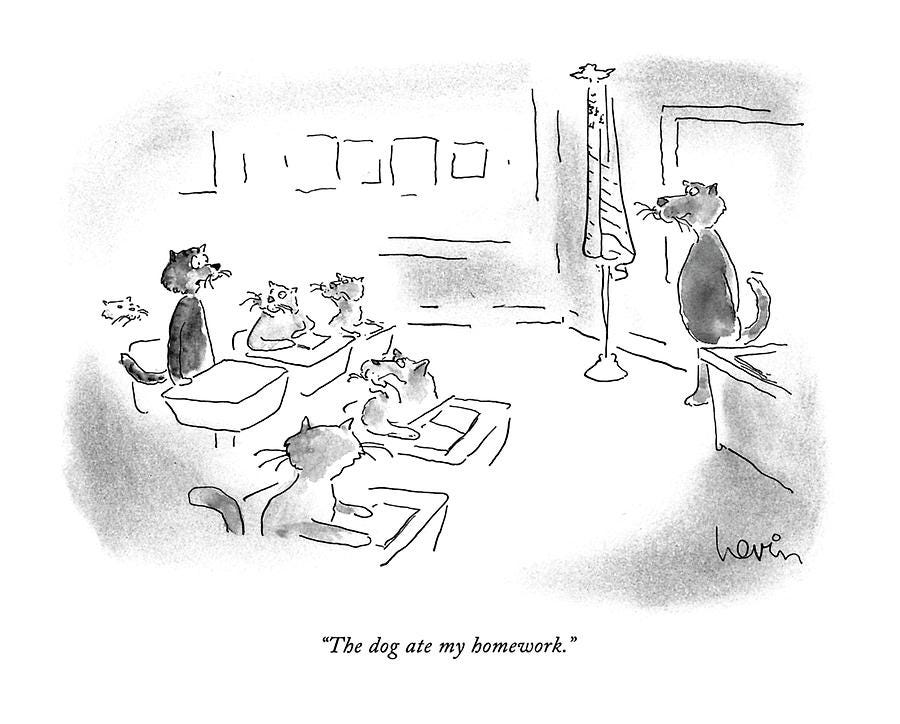

An interesting aspect of reputation is that others don't need to observe our every action to form an opinion about us. Often, the frequency of our behaviour is enough (Rich and Zollman, 2016). For example, consider a car mechanic who always recommends expensive repairs whenever you bring your car in for service. Even if you don't catch him in a lie, you may start to suspect that he’s not entirely honest. Similarly, a teacher may doubt a student who consistently makes excuses for not doing their homework, even without proof that the excuses are false.

This tendency to form opinions based on the frequency of behaviour explains why people typically follow a simple heuristic in their social interactions: they usually forgive one misstep but become less charitable when it is repeated. The Latin maxim errare humanum est, perseverare diabolicum (to err is human, to persist is diabolical) warns that while some missteps will be tolerated, repeated missteps will be judged as intentional. Indeed, tolerating repeated missteps would allow others to abuse our goodwill, as expressed by the saying “fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me”. One version of this heuristic, sometimes implemented in law, is the “three strikes rule”, whereby sanctions increase severely after a third infraction.

The fact that people's unobserved actions can be inferred from the observed proportion of the outcomes of their visible actions or statements casts light on two aspects of how gossip works.

First, while tales of hidden skeletons in the closet make for the juiciest gossip, they're not the most common. Such scandalous stories are relatively rare. Instead, gossip often focuses on the patterns of people's actions—the things they do consistently. This type of information is widely observed and easily shared, providing a pointillist picture of a person's character. When people gossip, they tend to talk about how helpful someone is (“she's always giving her time to help”), how supportive they are (“she’s there whenever you need her”), or how rarely they engage in undesirable behaviour (“she never misses church”). These details, pieced together from various sources, create a mosaic of a person's reputation.

Second, the idea that disreputable behaviour can be inferred from the frequency of actions also applies to the potential strategic disingenuous use of gossip. Even without direct evidence, we can infer whether someone is using gossip for their own benefit rather than to provide useful information simply by observing the proportion of negative gossip they share. If a person consistently spreads more negative gossip about others than the average person, they may be labelled a “gossiper” and viewed with suspicion. This suspicion extends not only to what they're saying in the moment but also to what they might say later about us to other people.

Negative gossip, therefore, comes with a potential cost for the speaker, especially if they have a weaker pre-existing relationship with the listener. This leads to lots of negative information remaining untold because people don't want to risk being seen as gossipers. It's one reason why some pieces of negative information are labelled “worst kept secret”: They are known by many people but not widely shared.8

Why reputation can unravel quickly

The gap between people's private views about reputation and the information publicly exchanged can lead to a situation of pluralistic ignorance, where most people are unaware that the majority share their perspective. This phenomenon explains the sudden unravelling of some people's reputations, which can seem strong one day and crumble the next. Such unravelling often follows a single incident where the person visibly behaves out of step with their perceived reputation or when one person decides to speak up, prompting others to come forward with their private information that contradicts the public image.

The fall from grace of a star like Ellen DeGeneres is a good illustration of such a phenomenon (among countless others). It started with a tweet from comedian Kevin Porter, who jokingly invited people to share stories about her being mean. He received more than 2,500 responses, revealing a strong discrepancy between her public persona and many people’s views about her private behaviour.

How our reputational concerns help explain collective crazes

An interesting aspect of reputation is that the way people “should” behave in society to get a good reputation is shaped by societal views. Typically, everyone adheres to the same views, manifesting as social norms. However, social norms can evolve, leading to uncertainty about the “right” thing to do. In such instances, individuals observe others for cues on how to behave. When everyone is watching each other, unsure about how social norms are evolving, social norms may shift in ways not necessarily aligned with private preferences. A reputational cascade can occur: individuals might act in a certain manner because they believe others perceive it as the correct action, even though many, or most, privately disagree. Scharfstein and Stein (1990) initially described this phenomenon in the context of financial managers:

Under certain circumstances, managers simply mimic the investment decisions of other managers, ignoring substantive private information. Although this behavior is inefficient from a social standpoint, it can be rational from the perspective of managers who are concerned about their reputations in the labor market. - Scharfstein and Stein (1990)

The notion of reputational cascade can elucidate herding behaviour in various contexts where individuals prefer not to risk being perceived as diverging from collective wisdom.

For instance, it is the case when a group of people are asked to give their individual opinions in a novel situation. Herding naturally occurs in such situations as following the crowd may seem safer. Even if the consensus is incorrect, one will not be singled out for mistakes, as the error is shared by the group. In line with this, it has been observed that figure skating judges tend to conform when assigning scores, avoiding positions as outliers (Lee 2008). Similarly, Nate Silver has convincingly demonstrated that polling companies engage in herding, adjusting their independent findings towards the polling average to avoid being too far from it.

The concept of reputational herding has also been used to explain the rapid emergence of new collective behaviours (Kuran, 1998; Hale, 2022).

If a particular perception of an event somehow appears to have become the social norm, people seeking to build or protect their reputations will begin endorsing it through their words and deeds, regardless of their actual thoughts. - Kuran and Sunstein (1999)

This mechanism offers insights into the origins of certain collective crazes. For example, during the Cultural Revolution, Chinese individuals suddenly began carrying around Mao's Little Red Book requesting others to do so too. Similarly, during the McCarthy era, many Americans denounced their colleagues for supposed "un-American" activities. These past collective crazes are sometimes interpreted as evidence that people “back then” were not as reasonable as we are today. An alternative interpretation is that the dynamics of reputational herding can occasionally engulf our societies, even if the individuals involved are fully rational and simply trying to maintain a good public record.

Our reputation is like a “second self”: not a reflection of our inner identity, but rather an image constructed by others' perceptions of us. Given our reliance on other people for success in life, their opinions about us significantly influence our social prospects. This explains our concern for others' views about us and why we dedicate considerable time and effort to managing our reputation and learning about (or sharing information on) the reputations of others.

This is the second of two posts on reputation. In the next posts, I will discuss communication games—the games we play in our everyday lives when discussing with other people. It is a fascinating topic on which many interesting things can be said to cast a light on the very nature of our interactions.

References

Ausubel, D.P., 1955. Relationships between shame and guilt in the socializing process. Psychological Review, 62(5), p.378.

Dunbar, R. I. Gossip in evolutionary perspective. Rev. General Psychol. 8, 100–110 (2004).

Engelmann, J.M., Herrmann, E. and Tomasello, M., 2012. Five-year olds, but not chimpanzees, attempt to manage their reputations. PLoS One, 7(10), p.e48433.

Feinberg, M., Willer, R. and Schultz, M., 2014. Gossip and ostracism promote cooperation in groups. Psychological Science, 25(3), pp.656-664.

Fonseca, M.A. and Peters, K., 2018. Will any gossip do? Gossip does not need to be perfectly accurate to promote trust. Games and Economic Behavior, 107, pp.253-281.

Frank, R.H., 1988. Passions within reason: The strategic role of the emotions. WW Norton & Co.

Hale, H.E., 2022. Authoritarian rallying as reputational cascade? Evidence from Putin’s popularity surge after Crimea. American Political Science Review, 116(2), pp.580-594.

Kuran, T., 1998. Ethnic norms and their transformation through reputational cascades. The Journal of Legal Studies, 27(S2), pp.623-659.

Kuran, T. and Sunstein, C., 1999. Availability cascades and risk regulation. Stanford Law Review, pp.4-1.

Landers, M., Sznycer, D. and Al-Shawaf, L., 2021. Shame.

Lee, J., 2008. Outlier aversion in subjective evaluation: Evidence from world figure skating championships. Journal of Sports Economics, 9(2), pp.141-159.

Origgi, G., 2017. Reputation: What it is and why it matters. Princeton University Press.

Page, L., 2023. Optimally irrational: The good reasons we behave the way we do. Cambridge University Press.

Plato. Laws.

Rich, P. and Zollman, K.J., 2016. Honesty through repeated interactions. Journal of theoretical biology, 395, pp.238-244.

Scharfstein, D.S. and Stein, J.C., 1990. Herd behavior and investment. The American Economic Review, pp.465-479.

Smith, A., 1776. The Wealth of Nations

Smith, R.H., Webster, J.M., Parrott, W.G. and Eyre, H.L., 2002. The role of public exposure in moral and nonmoral shame and guilt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1), p.138.

Trivers, R.L., 1971. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1), pp.35-57.

These feelings have, in turn, effects on our behaviour that can help us manage the propitious (pride) or inauspicious (shame) changes in our social relations.

Notably, this explanation of pride, shame, and guilt does not require these feelings to be associated with the conscious management of our reputation.

The mirror of guilt is a feeling of self-satisfaction that can often drive us to do the right thing even when nobody is watching.

Some evolutionary psychologists have proposed a different definition of guilt as encoding the “harm on others we value” (Landers et al., 2021) perhaps to capture the fact that our biological fitness is tied to kin and coalitional partners. I am not convinced by this definition. Introspection tells us that we can experience guilt for violating moral or religious norms, even when our actions don't directly impact those close to us. Feeling bad about such norm violation nonetheless makes sense as they would have a reputational cost if found out.

I discussed this point in Chapter 4 of Optimally Irrational (2023).

Going a step further, I also explained in Optimally Irrational that the triggering of our social emotions can be contingent on the strategically relevant elements of context. It may therefore be possible that even though guilt reflects an intrinsic motivation to behave well, this feeling may be boosted after being found out as a way to display credible signals of atonement and remorse.

See this section in a previous post for a quick description.

In comparison, it is often less reasonable to blindly trust companies with which you are making a one-off purchase. For instance, people who renovate their homes or have their houses built often find noticeable gaps between what they thought they were paying for and what is delivered. A US survey of people who had their house built found that 66% of them had some regret with the process of house building.

One can think of a movement like the MeToo movement, where practices that were not uncommon in some industries are suddenly condemned by many voices that were silent until then. Closer to behavioural sciences, one can think of the awareness of academic misconduct that pre-existed its formal indictment. After the revelation of the scandal involving Dan Ariely's papers, Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler wrote on Twitter “I have known for years that Dan Ariely made stuff up”.

Wonderful article! Thank you for mentioning my book on Reputation. But you forgot to list it in the bibliographical references!