The paradox of power

On the limitations of power without trust

In Aesop’s fable The Lion’s Share, a lion, a fox, a jackal, and a wolf form an alliance to hunt together. However, once the prey is captured, the lion claims all the spoils and threatens anyone who dares contest his decision. The Roman fabulist Phaedrus captured the lesson of this tale in his own adaptation:

Partnership with the powerful is always precarious. - Phaedrus (1st century CE)

This reality, however, leads to a paradox. The risks of allying with a powerful partner often make it difficult for dominant actors to prevail in games of alliances. In this post, I discuss this paradox of power and its interesting applications.

Being too powerful may lead others to league against you

The paradox of power arises because, in strategic interactions, other players anticipate the consequences of one player having greater power and adjust their behaviour accordingly.

The caveats of power in voting games

Political scientist Robin Farquharson (1969) illustrated this with the Chairman Paradox. In a voting committee where the chairman has a tie-breaking vote, they may paradoxically end up with less power than other members. Why? Anticipating the chairman’s tie-breaking advantage, other players may preemptively coordinate to avoid tie situations altogether. As a result, the chairman may never actually cast a decisive vote, rendering their formal authority meaningless in practice.

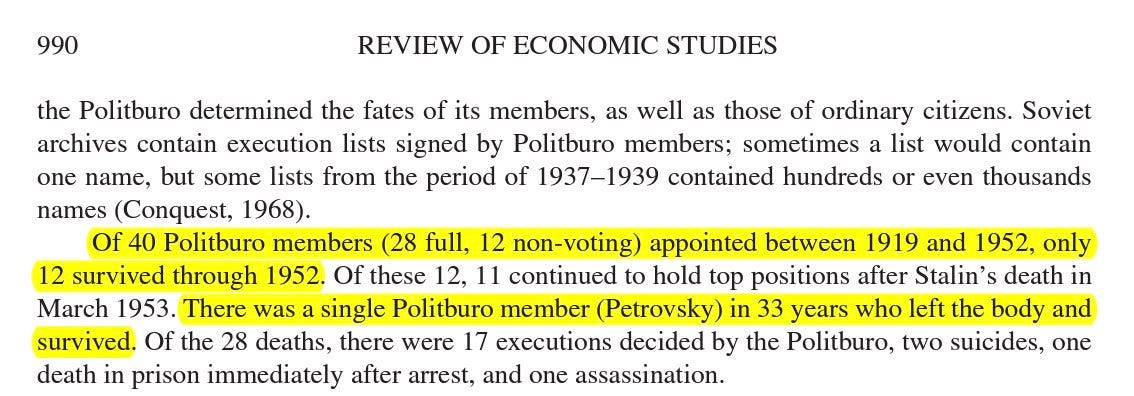

When the rules of the game allow for player elimination, powerful players may find themselves with a target on their backs. Economists Acemoglu, Egorov, and Sonin (2008) built a model of coalition formation in which a majority coalition can be challenged at any time. They found that strong players are often more likely to be excluded, as others preemptively remove individuals who might later dominate them. They illustrated this idea with the historical dynamics of the USSR, where elimination from the Politburo typically resulted in execution.

In such an environment, a powerful player faced greater risks, as illustrated by the demise of Beria. Second-in-command under Stalin, he became the most dominant figure after Stalin’s death, but shortly afterwards, other Politburo members coordinated against him and had him executed. A fictionalised depiction of these coalitional dynamics appears in the 2017 comedy The Death of Stalin.

Balancing power in international politics

The same strategic issues and questions arise at the international level. Like individuals, states can form coalitions. Those who perceive a larger country as a threat may form a counter-alliance to balance its power.

International politics in Europe has been characterised by such balancing strategies, which—along with heterogeneous geography that made land unification challenging—help explain why Europe has remained divided into multiple states. Any state that became too powerful faced a growing alliance of wary neighbours determined to restore the balance of power (Gulick, 1955).1

In his book on the history of strategy, Lawrence Freedman points out that Napoleon’s undoing was not just military defeat but also ineffectiveness in alliance building, despite his unprecedented success in winning battles.

Even the strongest individual state could be defeated by an organized coalition ranged against it and determined to restore equilibrium to the international system. This too Napoleon discovered to his cost. - Freedman (2015)

The importance of trust

The problem: the impossibility to commit

The difficulty powerful players face in securing allies can be traced to a fundamental issue: coalitional agreements are often not binding. In politics, a politician may break past promises. In geopolitics, a country can renege on prior commitments.

Who is there to prevent such betrayals? Often, no external authority exists to enforce coalitional agreements. This is particularly true in international relations, where no supranational entity can guarantee that states will honour their alliances. In such an environment, weaker states risk being at the mercy of powerful neighbours.

The idea that a stateless system fosters uncertainty and risk for weaker players long predates Hobbes’ Leviathan. The ancient Indian philosopher Chanakya articulated a similar principle, describing the “law of the fish”—essentially, the law of the jungle:

In the absence of a magistrate, the strong will swallow the weak - Chanakya (300 BCE)

Too big to prevail: The Russian example

This inability to credibly commit also has consequences for major powers. A dominant state may paradoxically find itself “too big to prevail” in the game of international alliances (Ke et al., 2022).

A striking example is Russia’s struggle to maintain influence over Eastern Europe and former Soviet republics. Many of these countries actively sought to distance themselves from Russia and join NATO instead. The expansion of NATO in the 1990s has often been framed as an aggressive move by the West. However, it was primarily driven by Russia’s neighbours, who feared a resurgence of Russian imperialism in the future (Sarotte, 2021).2 These states saw NATO as a protective alliance, one that could shield them from the risk of Russian expansionism.

Why is the US at the centre of a powerful network of alliances?

You might point out that despite the paradox of power, the United States remains extremely powerful and yet sits at the centre of a vast network of alliances. How does the paradox explain this? Why is the US an attractive coalition partner?

Game theory teaches us that cooperation can be self-enforcing—it does not necessarily require a third-party enforcer like a state or magistrate. Instead, cooperation can emerge as an equilibrium, where acting cooperatively builds a reputation for reliability, encouraging others to reciprocate. It is the fear of losing that reputation—and the benefits it entails in the long term—that makes continued cooperation advantageous in the short term.

The US holds its central position in the Western alliance system precisely because of the trust it enjoys among its partners. This trust is not based on blind faith from gullible partners, but rather on a long-established reputation. The US demonstrated its reliability by respecting and helping its allies, including with its decisive support to Britain and France in two world wars without later seeking territorial control in Europe.3

Trust is easily lost: Insights into Trump’s geopolitical moves

These insights are particularly relevant in assessing Donald Trump’s early decisions in his second presidency.

On Ukraine, the US had provided “assurances” in the 1994 Budapest Memorandum,4 in which Ukraine agreed to relinquish its nuclear arsenal to Russia in exchange for security guarantees from the US, the UK, and Russia. However, the Trump administration initiated direct negotiations with Russia over Ukraine’s future without consulting European allies, signaling that: Russia would keep its occupied territories and that Ukraine would not join NATO.

Regardless of whether this was the least bad outcome for a peace process, the fact that it served as the US starting position—effectively validating the first large-scale war of invasion in Europe in 80 years—sends a different message: it undermines the trust US allies can place in American security commitments.

Worse than neglecting allies, the Trump administration has turned against some of them: Canada, Denmark and the EU, even Australia. When Trump suggested that the US might need to take control of Greenland for security reasons, he did not rule out a possible military intervention. Such rhetoric was far outside the expectations of US allies. De facto, nothing prevents Trump from coercing some of its close allies. The geopolitical costs of such actions are, however, easily underestimated.

The US occupies its position at the centre of the world’s strongest alliance network because of trust.5 A good reputation is hard to gain and easy to lose. From a purely self-interested perspective, Trump’s show of force may yield short-term gains, but it risks long-term damage to the US’s international standing.

The position of a hegemonic power in coalition politics is, paradoxically, often based not on raw power alone, but on the ability to convince weaker players that this power will not be used against them. Trust is the key. By refraining from exploiting weaker allies, a powerful player can avoid the paradox of power and extend its influence through a broad alliance. It is easy to overlook the fact that this extended power rests on something as intangible as trust. But a dominant player ignores this reality at its peril. Once trust erodes, alliances collapse, and with them, the long-term benefits they provide.

This post is part of a series on coalitions. In the next post, I will look at the evolutionary roots of our egalitarian psychology.

References

Acemoglu, D., Egorov, G., & Sonin, K. (2008). Coalition formation in non-democracies. The Review of Economic Studies, 75(4), 987-1009.

Chanakya (2001). Kautilya's Arthashastra. Edited by B. K. Chaturvedi. New Delhi: Diamond Pocket Books.

De Mesquita, B. B., Morrow, J. D., Siverson, R. M., & Smith, A. (2004). Testing novel implications from the selectorate theory of war. World Politics, 56(3), 363-388.

Farquharson, R. (1969). Theory of Voting. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Freedman, L. (2015). Strategy: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gulick, E. V. (1955). Europe’s Classical Balance of Power: A Case History of the Theory and Practice of One of the Great Concepts of European Statecraft. New York: W. W. Norton.

Ke, C., Morath, F., Newell, A., & Page, L. (2022). Too big to prevail: The paradox of power in coalition formation. Games and Economic Behavior, 135, 394-410.

Phaedrus (c. 1st century CE, 1992). The Fables of Phaedrus. Translated by P. F. Widdows. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Russett, B. (2001). Triangulating Peace: Democracy, Interdependence, and International Organizations. New York: W. W. Norton.

Sarotte, M. E. (2021). Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Schroeder, P. W. (1994). The Transformation of European Politics, 1763-1848. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weeks, J. L. (2012). Strongmen and straw men: Authoritarian regimes and the initiation of international conflict. American Political Science Review, 106(2), 326-347.

Balancing is not the only strategy available to a country when facing a powerful neighbour; see Schroeder (1994) for a discussion of alternative strategies.

Western countries were often reluctant to expand NATO, as the net benefits of enlargement were not always clear. Existing NATO members did not require new members to ensure their own security, and adding countries closer to a powerful neighbour increased the risk of military entanglements. After the first wave of NATO expansion (1999-2004), Western European countries were hesitant to admit states outside the European Union. In 2008, Germany (under Merkel) and France (under Sarkozy) opposed Ukraine and Georgia’s candidacy. Later that year, Russia invaded Georgia and six years later, Russia invaded Crimea.

I wrote detailed threads (first and second) on Twitter about these issues at the start of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

After a short military occupation, the US handed control of Germany and Japan back to their local civil administrations. Today, pro-American attitudes are among the highest in the world in these two countries (here and here). This stands in stark contrast to the fear and resentment that Soviet rule left in Eastern European countries. This is not to suggest that the US can always be blindly trusted by its allies. Like any alliance, the US-led system experiences internal conflicts, but these fall far short of military coercion.

In addition to its history, the US benefits from being a liberal democracy, and liberal democracies rarely wage war against one another (Russett, 2001). The reason, in my view, is a simple question of incentives. War primarily benefits ruling elites, who enhance their status on the international stage in the event of victory (e.g., territorial expansion). However, the costs of war—in terms of human casualties and suffering—are borne by the population.

In a democracy, ruling elites have less incentive to start wars, as their tenure depends on popular support. Since the population bears the brunt of war, securing public backing for military action requires overcoming the political opposition’s arguments in favour of maintaining peace—typically, a hard sell. By contrast, in autocracies, rulers can often disregard public sentiment in the short term, giving them more leeway to impose their preferences (De Mesquita et al., 2004; Weeks, 2012).

These alliances are all the more important to the US that it now US faces, with China, an autocratic challenger that can match its industrial and military production.

Thank you for writing this Lionel.

I agree with you, a good reputation is difficult to build but easy to lose. Trump's geopolitical actions might be beneficial in the short term, but harmful in the long term.

I like taking concept back to first principles and this relates to Entropy, no? It's always harder to build something than it is to tear is apart.

This excellent article totally hits home when read from Canada.