Power balance and ideology

Why the cultural hegemony of the left erodes its epistemic standing

This is the second post on big questions surrounding the tragic political assassination of Charlie Kirk. Here, I discuss how power balance affects political debates.

In the aftermath of Charlie Kirk’s assassination, I want to return to what should seem a puzzling aspect of his success as an influencer. An outspoken conservative, he made his trade jousting with liberal students on US university campuses. He clearly had strong communication skills for this exercise, but as a non-college-educated man, how did he, video after video, seem to get the upper hand in agonistic debates with progressives?

The students Kirk debated were highly selected and exposed to what should have been high-quality training, with access to empirical data and academic books and papers. Why weren’t they able to “set the record straight”?

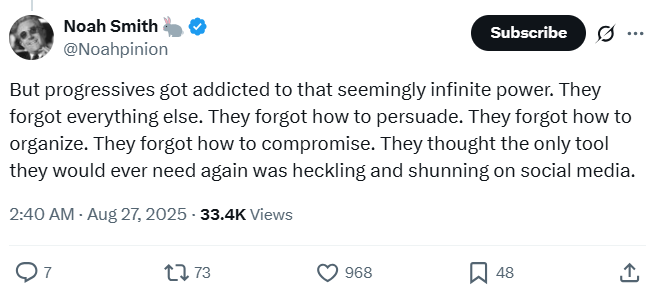

A comment from Noah Smith on Twitter points towards an answer:

I think Noah touches on something I have already discussed previously: in debates, epistemic strength and power are substitutes.1

The more a coalition faces the need to defend its narrative in an open political arena, the higher the pressure will be for logical consistency and factual accuracy. The more powerful a coalition is, the less pressure it faces in regard to the quality of the ideological narratives it produces. — Why science is politically disruptive

In other words, if you have more power, you need less epistemic strength to win arguments. This fact has significant implications for the quality of arguments produced on both sides of a political divide.

Ideological hegemony and epistemic erosion

A coalition’s ideology is a set of interwoven normative principles and factual claims backing a coalition’s demand to reshape the social contract (and the distribution of benefits between the different social groups). It is a tool of social bargaining, a way to negotiate a better share of the benefits of social cooperation.

An ideology is not primarily designed to be right (to point to the truth), but to win in the court of ideas (to be convincing). Its epistemic strength rests on the logical rigour and factual accuracy of its principles and claims. This strength is higher when normative principles are consistent and factual claims are backed by evidence commonly regarded as credible.2

A political ideology only needs to be logically consistent and evidence-based to the extent that it faces opposition and possible cross-examination. When an audience does not share your assumptions, you anticipate criticisms, which forces you to sharpen your reasoning. Psychologists Jennifer Lerner and Philip Tetlock, who studied reasoning under accountability, emphasised that it is largely the anticipation of criticism that generates pre-emptive self-criticism and improves argument quality.

When the views of the audience are completely unknown […] people who do not feel locked into any prior commitment often engage in preemptive self-criticism. — Lerner and Tetlock (1999)

By contrast, when an ideology becomes overly dominant within a community, its proponents no longer need to polish their arguments, nor do they receive meaningful pushback when they produce weak ones.

Such a lack of external pressure is all the more problematic because we are prone to motivated reasoning, crafting or accepting arguments that support our preferred conclusions. A dominant ideology, shielded from cross-examination, is likely to see its epistemic strength progressively erode as poor arguments—whether inconsistent or based on flimsy evidence—increasingly circulate unchallenged.

In his classic On Liberty (1859), John Stuart Mill described this logic:

the peculiar doctrines are more questioned, and have to be oftener defended against open gainsayers. Both teachers and learners go to sleep at their post, as soon as there is no enemy in the field. — Mill (1859)

As complacency sets in, the quality of arguments of the dominant side decays:

Instead of being, as at first, constantly on the alert either to defend themselves against the world, or to bring the world over to them, they have subsided into acquiescence, and neither listen, when they can help it, to arguments against their creed, nor trouble dissentients (if there be such) with arguments in its favour. From this time may usually be dated the decline in the living power of the doctrine. — Mill (1859)