Why science is politically disruptive

With a few examples

E pur si muove, Galileo is said to have muttered during his 1633 trial by the Roman Inquisition, where he was forced to publicly recant his proposition of a heliocentric model placing the Sun at the centre of the known universe instead of the Earth.1

Galileo’s public denial of his beliefs must be considered in the context of the risks involved at the time. In 1600, the philosopher Giordano Bruno was burned in Rome, in part for his cosmological views, supporting heliocentrism and an infinite universe containing many worlds similar to the Earth.

Today, the Catholic Church’s harsh reaction to ideas about the nature of the universe can easily appear over the top and unwarranted. The fact that the Earth orbits the Sun isn’t seen as conflicting with faith by religious institutions. Why did the factual reality about the movements of planets matter so much at the time, and why is it seen as benign for religion today? The answer is that political narratives are somewhat arbitrary, and scientific findings often happen to conflict with them. However, these narratives tend to be highly flexible over time and eventually adapt to scientific evidence.

The disruptive nature of science

Social groups that are politically organised defend, via their leaders, their interests in the political arena. This is typically not done in a raw and uncouth way (“we want more”). It is made via the defence of principles that are proposed to modify the existing social contract in favour of that group. Hence, workers do not just say “we want higher wages”, they say “labour deserves a higher share of the fruits of production”. People living in low-density neighbourhoods do not say “we don’t want high rises that will lower the value of our properties”, they say "we should preserve the character of the neighbourhood”, and so on.

The ideological narratives that justify the bundle of political views of a social group or coalition of social groups are not entirely, but still somewhat, arbitrary. First, the composition of a coalition is historically contingent and therefore might bundle positions that reflect the heterogeneity of its composing social groups. Second, these narratives are primarily selected for their convenience, not for their rigour. Inconsistencies and factual inaccuracies are avoided only to the extent that they could weaken the case being made. Political narratives put forward by social coalitions are like the arguments put forward in a courtroom. They are designed to make the best case for the interests of the considered party. It is only the risk of cross-examination that compels these arguments not to be overly logically inconsistent or factually inaccurate.

This nature of political ideology explains why they are often riddled with inconsistencies, as long as these are not too obvious. They also often rely on factual inaccuracies because convenient factual claims are made even with limited evidence.

These limitations are influenced by the power of a coalition. The more a coalition faces the need to defend its narrative in an open political arena, the higher the pressure will be for logical consistency and factual accuracy. The more powerful a coalition is, the less pressure it faces in regard to the quality of the ideological narratives it produces. That is why, in authoritarian states, the ruling coalition can make egregiously preposterous claims about reality without receiving any contradiction. For instance, the official newspaper of North Korea's ruling party once published an article claiming that Kim Jong-il could teleport to avoid being tracked by American satellites. It is likely that no one sent a critical letter about it to the editorial office.2

This description of the way political ideologies are shaped explains why science is politically disruptive: the ideas it generates do not necessarily align with the web of convenient claims the currently prevailing ideologies have happened to adopt.3

Consider Galileo’s case. The Church’s view was based on humans’ immemorial intuitive observation that the world is where we stand. The ground appears immobile, and things seem to rotate around it in the sky. The idea that this world, Earth, is the centre of the Universe is a fairly natural assumption when thinking that its creation was a god’s main goal. This geocentric view was so intuitive that the Church did not feel the need to state it officially. It is only after the publication of Copernicus' ideas in 1543 and the growth in their influence that the Church formally rejected heliocentrism as heretical and contradicting the Scriptures (in 1616).

The heliocentric idea is not in itself political, but it becomes so when it contradicts the ideological narrative of the Church. Such a challenge undermines not only the narrative itself but also the authority of those in the Church whose legitimacy depends on it. If the Church is found wrong about this, people may begin to question what else it might be wrong about.

Examples of scientific ideas disrupting the political debate

Galileo’s case is useful for appreciating the possible conflict between factual claims in prevailing ideologies and novel scientific ideas. We are far enough from his time for the scientific view he supported to now be consensual, and for the Church’s views to be seen as misguided and unnecessary.

With this insight, let us look at some modern examples where scientific findings are caught in the crossfire of political debates.

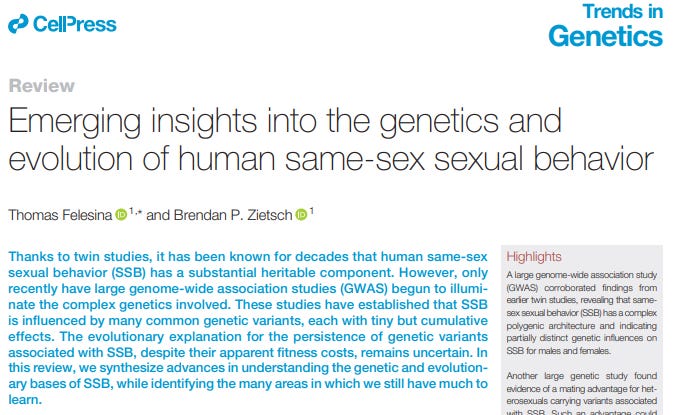

Nature of homosexual preferences

What is the origin of homosexual preferences: Nature (e.g. genes) or nurture (e.g education or culture)? Before World War 2, the proposed explanations were diverse. The biological explanation of homosexuality was just one of them. The war and the mass killings in Nazi Germany changed this. The view that homosexuality was a biological defect had contributed to justifying the imprisonment and execution of homosexuals. In reaction to this fact, biological explanation lost their appeal after the war. In her book An American Obsession (1999), on the history of homosexuality and its treatment in the US, Jennifer Terry describes this evolution:

Following widespread revelations about The horrors of Nazi medicine, which had sullied the reputation of hereditarian and biological explanations for human behavior, the pendulum lum swung toward psycho- and sociogenic arguments that privileged “nurture” over “nature” as the origin of behavioral variations such as homosexuality. — Terry (1999)

In conservative religious circles, criticism of homosexuality shifted to characterising it as a choice, a wrong one, that people could opt out of. From this perspective, condemnation of homosexuality and appeals to “convert” homosexuals were justified. For instance, the Family Research Council, a US conservative and Christian organisation, rejects homosexuality as unnatural:

Homosexual conduct is harmful to the persons who engage in it and to society at large, […]. It is by definition unnatural, and as such is associated with negative physical and psychological health effects. While the origins of same-sex attractions may be complex, there is no convincing evidence that a homosexual identity is ever something genetic or inborn. — Family Research Council

As a remarkable reversal, a biological explanation of homosexuality (“born this way”) could now be useful as an answer to such conservative criticisms. Since biological differences being used to criticise homosexuality were now off-limits for conservatives, there was little downside in them. For gay rights activists, biological explanations of homosexuality became a debate winner: convenient to reject calls to change behaviour and safe from being used against homosexuals.4 In his book A Place at the Table (1994), the gay rights advocate Bruce Bawer describes this logic:

To speak of homosexuality as something of which one can approve or disapprove, something that one can endorse or refuse to endorse, is to distort its nature, to pretend that it is a matter of choice. One can approve or disapprove of somebody's actions, opinions, beliefs; but it is meaningless to speak of approving or disapproving of another person's innate characteristics. To say that one approves or disapproves of somebody's homosexuality is comparable to saying that one approves or disapproves of somebody's baldness or tallness. — Bawer (1994)

In that context, the empirical evidence coming from science that homosexuality is tied to biological realities such as genes, exposure to prenatal testosterone and brain wiring5 has been welcomed by gay activists as vindicating their position. Science has here been contradicting the conservative side of politics.

We can recognise that the fact these scientific findings clashed with conservative narratives was purely contingent. Without the atrocities of the Second World War, it is easy to imagine an alternative reality in which criticism of homosexuality rested on claims of biological difference, making scientific evidence for such differences unwelcome on the progressive side of politics.

Scientific findings on biological differences in sexual orientation are not inherently political, on the right or the left. They happened to be politically relevant only because political sides tied their argument to specific factual claims.