Morality works without absolute moral truths

Replacing theories of the Good and the Right with a theory of the Seemly

In this series of posts, I tackle the big question of fairness and morality: what it is and where our moral sense comes from. In the two previous posts, I have argued that morality does not need religious foundations to make sense and that there are no absolute moral truths. Here, I discuss how to think of morality when we abandon these seemingly reassuring ideas.

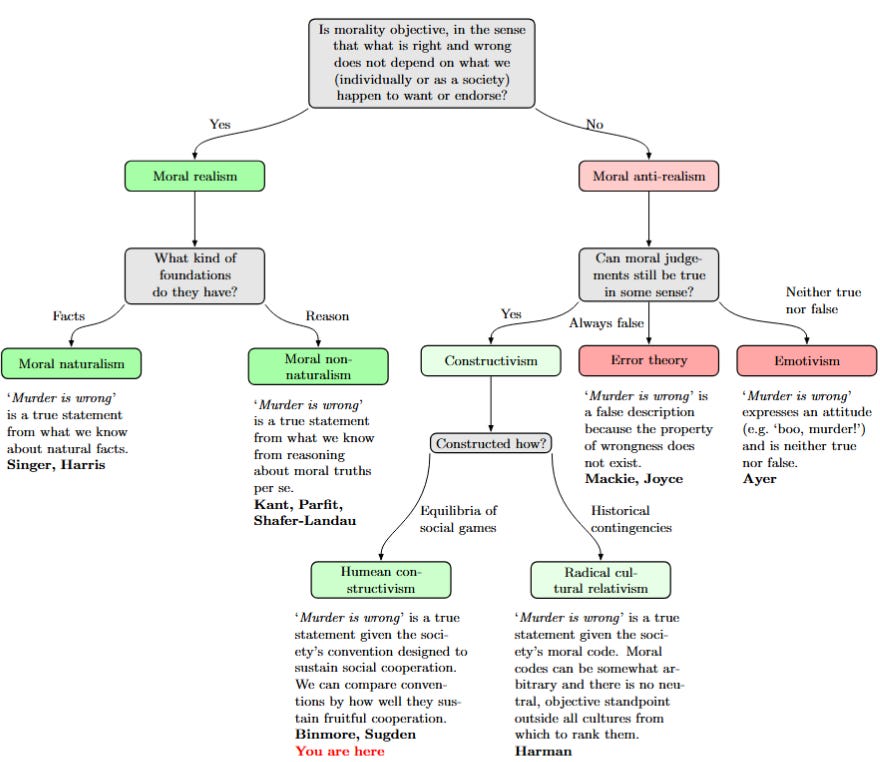

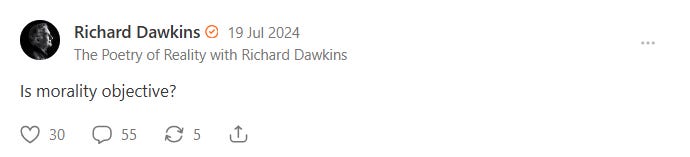

In a note last year, Richard Dawkins asked a simple question: is morality objective? Professional philosophers often put the question this way: are there statements that are truth-apt (they can be right or wrong) and whose truth is stance-independent (whether they are right or wrong does not depend on people’s thoughts or preferences about it).

In the previous post, I argued that the answer to that question is negative: we don’t have good reasons to assume that there are moral truths “out there”. Such an answer is sometimes met with shock and possibly horror. The philosopher Rudolf Carnap reports an anecdote about how people reacted to his claim that value statements (including moral ones) do not describe facts and cannot be proved true or false. One of his colleagues even pondered whether he should call the police to put him in jail.

According to these critics, to deny to value statements the status of theoretical assertions and thereby the status of demonstrating their validity must necessarily lead to immorality and nihilism. In Prague I found a striking example of this view in Oskar Kraus, the leading representative of the philosophy of Franz Brentano. I heard from the students that in one of his seminars he characterized my thesis of the nature of value statements as so dangerous for the morality of youth that he had seriously pondered the question whether it was not his duty to call on the state authorities to put me in jail. — Carnap (1963)1

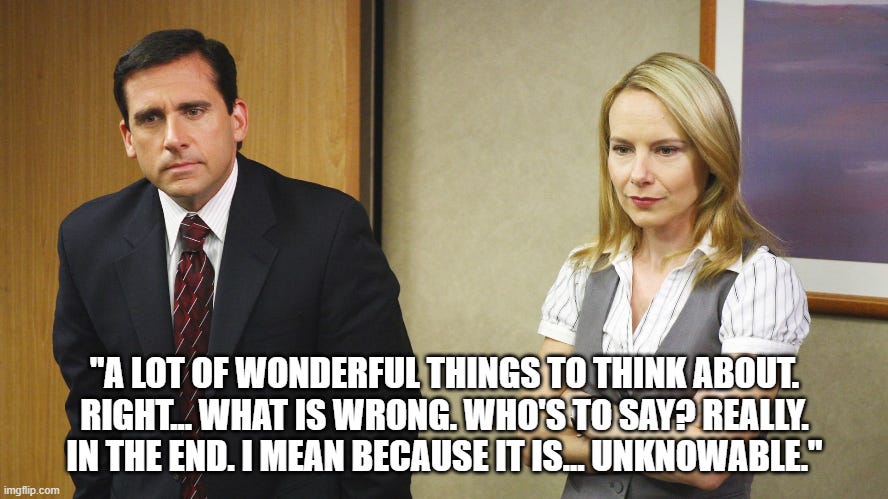

Carnap’s story captures a familiar fear: once we give up on absolute moral truths, we are left with moral chaos.

Until now, my posts on the topic have been mostly about pushing back against these widespread intuitions and against established philosophies building on them. Now is the time to flesh out more how we can think of morality from a naturalistic perspective, once we abandon the idea that there are absolute moral truths “out there”.

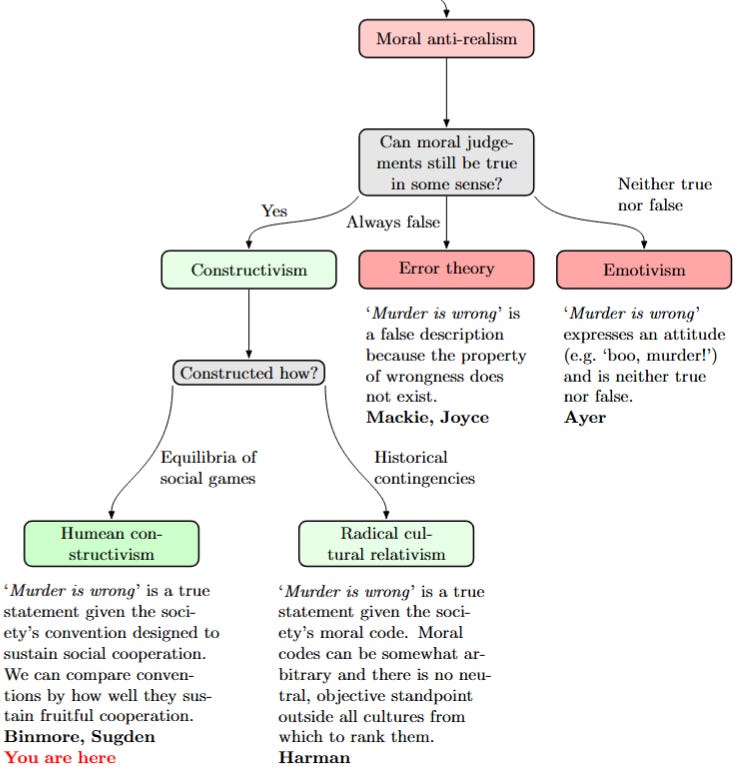

Locating the naturalistic position in the space of moral philosophy

For most people, ethical discussions often seem a bit mysterious. What is right? What is wrong? And how do we know how to answer these questions?

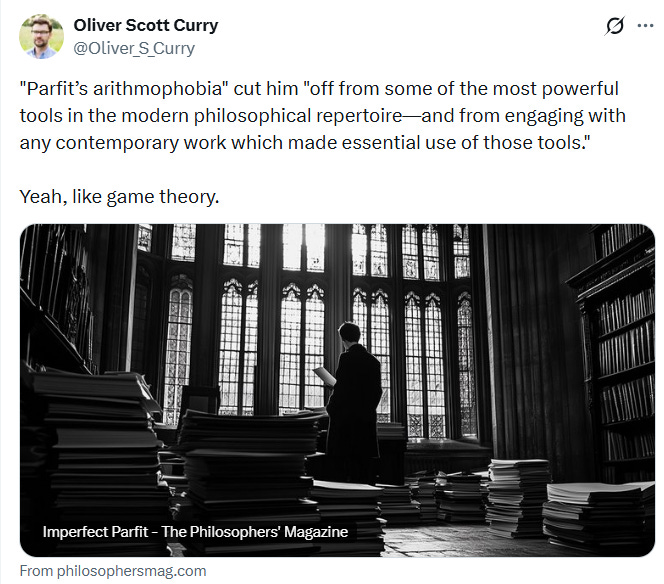

Metaethics—the branch of philosophy that looks at what morality is—can seem daunting. It is filled with abstract notions and technical terms. Early in his career, prior to producing the work that would end in his landmark book on the topic, On What Matters, Derek Parfit had purposely stayed away from that field. He is said to have told a colleague about it:

I don’t do metaethics. I find it much too hard. — Parfit2

Here, I provide a quick introduction to metaethics that breaks down the different philosophical positions based on answers to a few key questions. This makes it easier to locate where the naturalistic position I am developing here stands.3

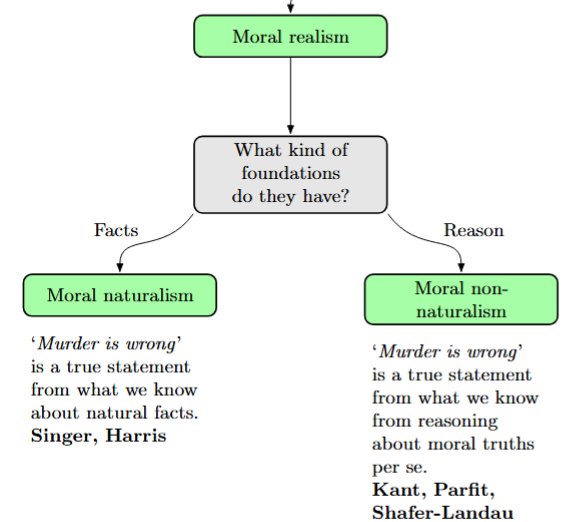

Moral realism

The first question is the one asked by Dawkins: is morality objective? Those answering yes are “moral realists”. As I indicated in my last post, an international poll of philosophers suggests that a majority of them endorse this view. The bulk of my post was dedicated to arguing against it.

One can think of two types of justifications for such a position. The first aims to ground an objective morality in natural facts. This “moral naturalism” is the position adopted by thinkers like Peter Singer and Sam Harris.4 It starts from factual descriptions of human experience (for example, that pain is undesirable and happiness desirable). It then argues that we can take an evaluative stance on this basis (for example, that pain is “bad” not just for the person, but in some higher sense that gives us a moral duty to reduce it).

Criticism of moral realism. This introduction of an evaluative stance, not grounded in natural facts, does all the work here: it smuggles an ought into the theory. It does not show that morality is objective. It assumes it. It is a logical leap that the reader is free to make, but it is not warranted by a naturalistic approach.

The second approach is to say that reasoning itself can help us identify moral truths. This approach is labelled “robust realism”, it is the one held by philosophers like Immanuel Kant and Derek Parfit.

Criticism of robust realism. I previously discussed Parfit’s argument.5 His claim to only use reason to find moral truths is a bit incorrect. In the end, he relies on our moral intuitions as a kind of primary ground upon which to build his theory: he investigates our intuitions with thought experiments and tries to build a theory which rationalises our “reasoned intuitions” (i.e. intuitions that resist some kind of rational investigation about how right they are). The problem here is that we have a very good naturalistic account of why we would have moral intuitions, based on evolutionary explanations. There is therefore no reason to assume that the existence of moral intuitions is evidence of objective moral truths “out there”.

Moral anti-realism

Let’s assume we abandon moral realism. A question we can ask next is: ”OK, morality is not objective in an absolute way, but can moral statements nonetheless be considered true or false in another way?”

Here, one option is to say no. Moral statements are neither true nor false, because moral statements do not refer to a moral reality that can make them true or false. Instead, moral claims reflect our preferences. Hence, when we say “murder is wrong” we just mean “I really don’t like murder”. This approach, proposed by philosopher A.J. Ayer,6 is called emotivism. It is also nicknamed the boo-hurrah theory of morality. A statement like “murder is wrong” just means “boo murder” and “charity is good” just means “hurrah charity”. Our moral statements, therefore, reflect our feelings about things.

Criticism of emotivism. I see at least two issues with emotivism. First, identifying moral statements with moral feelings raises the question of why we have them and why they take the particular form they do. Could we have any type of moral feelings? Could we expect “hurrah murder” to be as likely as “boo murder” as a feeling? If not, why? Emotivism leaves this question unresolved. A second issue is that moral statements seem to have a logical structure (this is called the Frege–Geach problem).7 We can make apparently valid inferences such as “murder is wrong, so intending to murder is wrong” or use moral claims inside conditionals: “If murder is wrong, then paying someone to murder is wrong.” But emotivism rejects the idea that moral claims can be true or false, so it is not clear why they should behave in arguments as if they were the kind of sentences that can be true or false. If moral language is only a matter of expressing feelings, why couldn’t someone consistently say “boo murder” and “hurrah for murder intentions,” in the same way that they can dislike vanilla ice cream but like chocolate ice cream?

Another possible answer is to say: yes, moral statements can be true or false, but ordinary positive moral judgements are all false! There is no realm of objective moral facts “out there”, so when we say “murder is wrong” we are systematically mistaken about what exists. This view, famously defended by John Mackie and known as error theory, holds that moral judgements are always in error. From that perspective, much traditional moral debate on moral truths looks a bit like the supposed Byzantine debates on whether angels are male or female: it discusses claims about presupposed entities that do not exist.8

Criticism of error theory. Saying that moral claims are wrong when they assume absolute moral truths is fine. But it doesn’t follow that moral claims can’t be true or false in a more limited way. The sentence “You can’t do that”, frequently uttered when playing board games, can be true or false even though it does not rely on any absolute truths “out there”, only on the existence of commonly agreed rules of play. In fact, Mackie invites us to look at empirical studies of how morality actually works in human societies, and Binmore saw his own work as following in Mackie’s footsteps.

Mackie tells us to look […] for a framework within which to make sense of […] anthropological data, he directs our attention to Von Neumann’s theory of games. — Binmore (2005)

The naturalistic approach I develop here answers yes to the question of whether moral statements can be true or false. However, if they are not true or false in the sense of moral realism, in what sense can they be true or false? The answer is that different social groups can have different moral rules. Within each group, a statement such as “X is wrong” can be true or false given these rules.

If this is the case, it is natural to ask where these rules come from: how are they constructed? One possible answer is radical cultural relativism. This position takes the view that different moral systems happen to be what they are in a given society for historically contingent reasons that might be arbitrary. These moral systems are not comparable across times and places. They are “incommensurable” (there is no measure we could use to compare them). As a result, we are never able to compare moral rules across cultures because we do not have a valid external standpoint from which to do so.9

Criticism of radical cultural relativism. Radical cultural relativism has too many unanswered questions. It does not offer a positive theory of how moral systems emerge and evolve. Why do societies have the moral systems they have? Are they arbitrary? Can they prescribe any kind of action at all? If so, why should we care about them? Why do people follow them?10

The view I develop here does not pursue this route. It posits that moral systems do not simply happen to be what they are for purely historically contingent reasons. They emerged from cultural evolution to serve a function: to help foster and regulate social cooperation. This approach is often referred to as Humean constructivism because philosopher David Hume was perhaps the earliest proponent of this view:

The rules of equity or justice depend entirely on the particular state and condition in which men are placed, and owe their origin to that utility which results to the public from their strict observance. — Hume

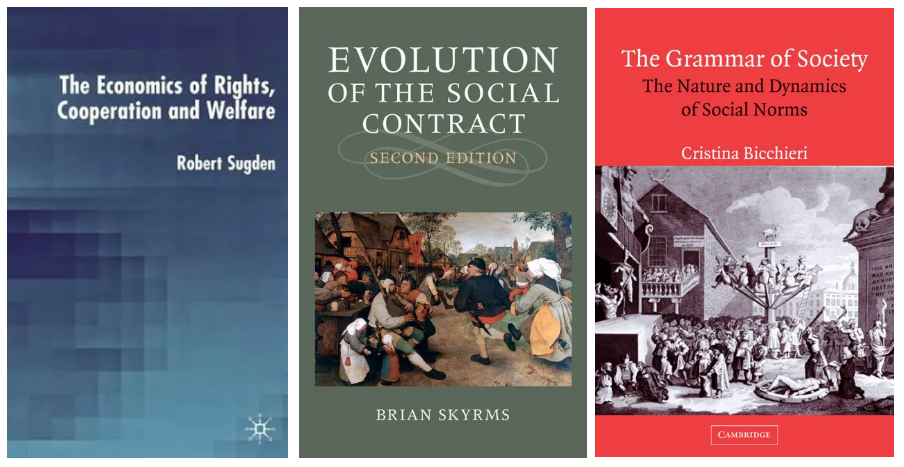

Surprisingly, this approach remains a blind spot in mainstream academic metaethics. The view I am developing here builds on important contributions by authors such as Robert Sugden, Brian Skyrms, Cristina Bicchieri, and Ken Binmore, whose work is largely ignored in standard metaethical discussions. A quick look at the main textbooks is revealing. Neither these authors, nor their method of inquiry—game theory—is mentioned in van Roojen’s Metaethics (325 pages), Miller’s Contemporary Metaethics (570 pages), or Chakraborti’s Introduction to Ethics (768 pages).

Binmore noted this somewhat peculiar absence of engagement with game theory in the philosophical literature on morality. When philosophers have to look into the possible insights game theory can bring to our understanding of morality:

It is at this point that scientific philosophers tend to falter. Game theory books are mostly written by economists, who use an exotic vocabulary and complicated mathematical equations. — Binmore (2005)

I strongly agree with Binmore that this is a pity. In a way, it is not warranted, as many important findings from game theory can be explained simply. Indeed, it is the standpoint of this Substack to bring some of its key insights in a faithful but approachable way.

[…] there is nothing arcane about game theory. On the contrary, what has to be explained in this chapter is embarrassingly easy. The exotic vocabulary and the fancy equations of game theory books are just more of the dust that scholars always kick up lest it be found out that what they have to say isn’t very profound. — Binmore (2005)11

As a result of this relative absence in metaethics, many moral philosophers are likely less familiar with the conceptual stance I present and may, on the basis of my previous post against moral realism, have been unsure where to locate it: emotivism? cultural relativism? error theory? This post (and the next) places this perspective in an approach that stands mostly outside the bulk of the discussion in metaethics, and yet is a position that is conceptually solidly grounded in our understanding of human interactions.

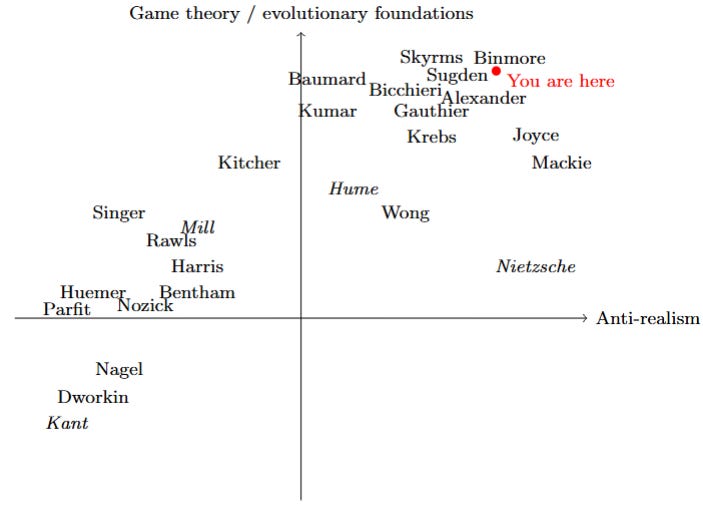

Another way to represent what distinguishes this position from most metaethical positions is to map these positions in a diagram distinguishing both realism from anti-realism and game-theoretical/evolutionary foundations from an absence of such foundations. The graph below does this for a non-exhaustive list of thinkers, blending classical philosophers and more modern thinkers.12

A moral theory of the Seemly

Having located this approach in the intellectual space of moral philosophy, it is now time to flesh it out and describe what vision it offers about morality. It is a big challenge to explain it simply, while doing it justice within the space of a Substack post. Here I will describe what it stands for. In the next post, I’ll discuss the implications of this position and compare these implications to other ethical positions.

The Good, the Right and the Seemly

Binmore distinguishes two main ways of thinking of morality as objective “out there”. The first is to assume that some things have an objective value and we ought to act to foster the presence of this value in the world. Such theories are called consequentialist. We can call them theories of the Good. The second is to assume that there are some fundamental moral principles out there that we ought to follow. Such theories are called deontological. We can call them theories of the Right.

A Humean constructivist approach rejects the claim that there are absolute moral truths out there—be they values or principles—that should guide our actions. Instead, it posits that our moral code is a human creation that serves to foster social cooperation.13

Having rejected the theories of the Good and the theories of the Right, Binmore labels his approach a theory of the Seemly, that is, a theory of morality as what is appropriate given social conventions about morality.

I try to capture this down-to-earth attitude to morality by calling it a theory of the seemly. Although theories of the seemly aren’t currently popular among moral philosophers, they have a long and respectable intellectual history. Aristotle, Epicurus, and Hume are perhaps the most famous Western exponents of the approach, but if one could mention only one name it would have to be that of Confucius.14

Within a theory of the seemly, things aren’t good or right in themselves; they are good or right because they are generally held to be good or right in a particular society. — Binmore (2005)

Thinkers like Robert Sugden, Brian Skyrms, Cristina Bicchieri and Ken Binmore develop such a theory of the Seemly by using game theory to explain the content and inner workings of moral systems. In short, this view relies on two key ideas. First, moral rules are equilibria of social games: they regulate stable patterns of social interactions. Second, these rules have emerged and persisted because they help solve recurrent coordination and conflict problems in ways that are, on balance, advantageous for enough members of the society to be stable.15

Moral rules are rules of the Game of Life

From this perspective, if there is an “ought” to follow these rules, it is not an unconditional mysterious ought coming from intangible moral values and principles that apply universally. We ought to respect moral rules because they are the rules of the social games we play. If you start playing Association Football (soccer), you should not grab the ball and run towards the opposite goal. Why? Because “handball is wrong” in football. And if you want to play football, you should respect that rule.

You might still ask, but in what sense ought we to abide by moral rules? Why shouldn’t we be happy instead just doing what we want? Here again, the explanation is no longer mysterious. You ought to abide by moral rules because they are an equilibrium of the social games you play. As a consequence, they are self-enforced by sanctions built into the game for those who do not respect them. It is perfectly meaningful to say something like “If you don’t want to be penalised, you ought to respect the rules”. This is a conditional ought, which is rational for you to follow, given the rules of the game. It is not an unconditional ought based on some assumed external moral truth.

I expect that this deflationary account of moral claims—i.e. an account which reduces the meaning of moral claims—will feel unsatisfactory to many. Isn’t morality radically more important than the rules of a sport? Some may point out that we feel more strongly about statements like “murder is wrong” than about “handball is wrong in football”.

The answer here is that yes, moral rules are much more important to us than sporting rules because moral rules are the rules of the Game of Life, the one that determines our success and setbacks in life, at work, with friends or romantic partners, with family members, and so on. It makes perfect sense for us to have a moral sense that makes us care greatly about how the Game of Life is played. There is no reboot and no respawn in this game, and it determines everything that matters to us.

Our moral sense, shaped by eons of evolution, is designed to provide us with emotions that help us play the Game of Life successfully. Any deviation from the moral code puts us at risk of future sanctions: blame, ostracisation, and even, in some cases, violence. Our moral emotions track the costs of deviations and bring them back into our present. They embed this shadow of the future in our daily experience. Talking about our moral cognition, cognitive scientists André et al. (2022) write:

[…] morality is not a set of rigid and stereotyped principles, but a flexible context-dependent calculator of what one must do to secure a good reputation and attract future cooperative investment from others.

Such an explanation might seem to conflict with the phenomenology of our experience of moral behaviour—i.e. how we experience engaging in making moral judgements. Moral feelings are typically experienced as primary feelings, not the reflections of some practical trade-offs about future payoffs. Isn’t this discussion of “calculations” misguided?16

It is important, here, to stress the two different levels of explanation of behaviour in evolutionary theory: ultimate explanations are about why a type of behaviour was selected by evolution, while proximate explanations are about how such types of behaviour are generated by our cognition. Saying that our moral sense is designed to track the payoffs of respecting or deviating from moral rules is an ultimate explanation. But, in our everyday lives, we typically choose to behave morally because we experience moral emotions, this is the proximate explanation of our behaviour. And our moral feelings can be strong because the stakes of the Game of Life are high.

Humean constructivism, in spite of a coherent conceptual framework grounded in ideas and results from game theory, is marginal in mainstream ethical discussions. The reason might come from the technicality of game theory, but also possibly from the seemingly less appealing view that morality is not grounded in absolute principles but in social conventions.

Aside from intellectual considerations, theories of the Seemly do not have the same social cachet as the grandiose theories of the Good and the Right. But perhaps the fact that people like me are moved to write books like this is a sign that the time for Seemliness has come. — Binmore (1998)

However grandiose the theories of the Right and the Good might be, they will only lead us to err endlessly in conceptual mazes if they are misguided. From that perspective, having the epistemic courage to abandon these absolute views and accept the social nature of morality opens the way for us to attain a greater clarity on what morality is and how it works.

Derek Parfit started his highly influential book Reasons and Persons with a quote from Nietzsche that reflects his view that abandoning religious foundations for morality opens us to a radically new understanding of morality, something real but secular. In the same way, the Humean constructivist perspective on morality opens a radical perspective, different from much that has preceded it in moral and political philosophy, enlightening even if a bit daunting in parts.

At last the horizon appears free to us again, even granted that it is not bright; at last our ships may venture out again, venture out to face any danger; all the daring of the lover of knowledge is permitted again; the sea, our sea, lies open again; perhaps there has never yet been such an “open sea”. — Nietzsche

References

André, J.B., Fitouchi, L., Debove, S. and Baumard, N., 2022. An evolutionary contractualist theory of morality. PsyArXiv. May, 24.

Ayer, A.J. (1936) Language, Truth and Logic. London: Gollancz.

Bicchieri, C. (2006) The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Binmore, K. (1994) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 1: Playing Fair. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Binmore, K. (1998) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 2: Just Playing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Binmore, K. (2005) Natural Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Binmore, K. (2012) ‘Kitcher on Natural Morality’, Analyse & Kritik, 34(1), pp. 129–140.

Carnap, R. (1963) ‘Intellectual Autobiography’, in Schilpp, P.A. (ed.) The Philosophy of Rudolf Carnap. La Salle, IL: Open Court, pp. 3–84.

Chakraborti, C. (2023) Introduction to Ethics: Concepts, Theories, and Contemporary Issues. Singapore: Springer.

Edmonds, D. (2023) Parfit: A Philosopher and His Mission to Save Morality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hume, D. (1751) An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals. London: A. Millar.

Mackie, J.L. (1977) Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong. London: Penguin.

Miller, A. (2003) An Introduction to Contemporary Metaethics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1882) The Gay Science. (Various editions; citation here refers to the work from which the closing passage is taken.)

Parfit, D. (1984) Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Parfit, D. (2011) On What Matters. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skyrms, B. (1996) Evolution of the Social Contract. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sugden, R. (1986) The Economics of Rights, Cooperation and Welfare. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

van Roojen, M. (2015) Metaethics: A Contemporary Introduction. New York: Routledge.

von Neumann, J. and Morgenstern, O. (1944) Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Westermarck, E. (1906–1908) The Origin and Development of the Moral Ideas. London: Macmillan.

I found this quote in a recent Substack note by Charles Egan. Carnap refers here to value statements in general (ethical, aesthetic, and so on).

Edmonds (2023)

For philosopher readers: my choice of exposition is slightly different from common expositions in metaethics that start with a more fundamental question: Can moral claims be truth-apt (i.e. are there moral claims that can be either true or false)? I opted to start from the question “is morality objective?” as it seems a more intuitive way to enter the discussion for a general audience. The answer to the truth-apt question is automatically yes when answering that morality is objective, while it needs to be answered at the second level when morality is not objective. I also opted not to include every option out there (e.g. prescriptivism, subjectivism) for simplicity.

“Naturalism” refers to the view that all that exists is part of the natural world studied by the sciences, with no supernatural entities or properties. Moral naturalism shares with my naturalistic approach the fact that it starts from naturalistic foundations. However, moral realists have to – at some point – smuggle in an ought when they argue that some natural properties – like well-being – count as morally important (e.g. “have value”). The normativity does not stem from the natural facts; it comes from an evaluative stance about what is to count as the human good. Since naturalists do not posit anything outside natural facts (e.g. no divine entity), this evaluative stance is introduced out of thin air. This sleight of hand can work as a rhetorical move because it taps into our moral intuitions (e.g. we care about others’ well-being). But formally, it introduces a logical leap in the argumentation.

Some moral naturalists might answer that the evaluative stance is a premise, like an axiom. But then it is fair to point out that it is usually not laid out explicitly as such. A clear axiom would be fine as a starting point. But it would, in effect, assume what the theory set itself to prove: that we can have true or false moral statements in an objective sense. Such an axiom would therefore be a skyhook.

I will discuss Kant’s influential take in a specific post later.

Ayer was a logical positivist. This school of thought, highly influential in the early 20th century, argued that many traditional philosophical discussions rely on statements that do not genuinely make sense as claims about the world. Key targets of logical positivism were metaphysics and theology. For them, a statement is cognitively meaningful only if it is either analytically true (true by definition) or empirically verifiable. Statements that are neither analytic nor verifiable are not genuine assertions of fact: they do not have a truth value and are, in that strict sense, cognitively meaningless, even if they may still express emotions or attitudes.

For the philosopher reader: the Frege–Geach problem (Geach 1965) is a classical objection to emotivism. If moral sentences just express attitudes and are not truth-apt, it is hard to explain why they behave in arguments (e.g. conditionals, modus ponens) as if they had truth-conditions. Quasi-realists such as Blackburn (1984, 1993) respond by showing how an expressivist can “earn” talk of truth and logical consequence by imposing coherence constraints on our pattern of attitudes. They keep the idea that moral judgements express attitudes rather than facts, but argue that if these attitudes are organised in a careful, consistent way, we can still talk about moral claims being true or false and about some moral arguments being valid. Very roughly, the logical patterns we see in moral reasoning then reflect which combinations of attitudes we can live with without running into inconsistency.

By contrast, the Humean constructivist view I develop here gives a natural answer to the Frege-Geach problem: moral claims are truth-apt within a moral system, and since moral systems are equilibria of social games, they come with built-in structural constraints, so not anything goes and the logical relations between moral claims reflect the underlying equilibrium.

This trope is, in fact, a later Western caricature: medieval Byzantine theologians did debate technical questions about angels, but the famous “sex of angels” story was popularised much later in Western Europe as a way of mocking scholastic and Byzantine theology.

More precisely, we can perfectly well have preferences about other moral rules based on our own morality, but we don’t have a way to make objective judgements about other moral rules.

To be fair, I am not saying that cultural relativists necessarily claim that moral rules are arbitrary, but by not providing a positive theory of how moral systems are shaped, they open the way for such readings.

Here Binmore is, if anything, too modest. There are some arcane parts to game theory and indeed Binmore’s books are in part unreadable to the non-initiated. His book Natural Justice aimed to make his message more accessible, in it he admitted that his first two books were not an easy read:

[…] my Game Theory and the Social Contract sold reasonably well. But it isn’t a book for the general reader. It is an academic work with long footnotes and earnest asides considering abstruse objections. As always in such books, it discusses much literature of marginal relevance in the hope of disarming critics who would otherwise challenge its author’s scholarly credentials. Worst of all are the equations—each of which halves a book’s readership. — Binmore (2005)

Note that this is not a diagram of political positions. For example, the philosophies of Rawls (egalitarian) and Nozick (libertarian) lead to very different political prescriptions. It is a diagram of their epistemic positions about what morality is and where it comes from.

Saying that morality is a human creation doesn’t imply that people necessarily sat down and decided to design and adopt a moral code. Instead, it is usually the result of a long process of cultural evolution.

In addition to Hume, previously quoted, here are some statements from these thinkers about morality as related to social conventions:

Natural justice is a symbol or expression of usefulness, to prevent one person from harming or being harmed by another. — Epicurus (Principal Doctrine 31)

If contrary to ritual, do not look; if contrary to ritual, do not listen; if contrary to ritual, do not speak; if contrary to ritual, do not act. — Confucius (Analects 12.1)

Without reducing morality to conventions, Aristotle saw morality as partly conventional:

The things which are just by virtue of convention and expediency are like measures; for wine and corn measures are not everywhere equal […] Similarly, the things which are just not by nature but by human enactment are not everywhere the same […] — Aristotle (Nicomachean Ethics V.7)

To be clear, this is not to say that all moral codes fit our moral intuitions in our present society. We may find some moral codes accepted in some other society quite shocking relative to our own moral standards. I will look at the question of comparison of morality across societies in my next post.

For sure, it would be naive or disingenuous to say that there is never any calculation in moral reasoning. Who has never weighed the pros and cons of violating a moral rule? But, at the same time, explicit calculations seem, to a large extent, undesirable in moral considerations. I’ll discuss this aspect of our moral judgement in a later post.

Really nice post, though of course I can't help but pick some nits with the taxonomy.

First, I'd dispute that Humean constructivism is all that marginalized in contemporary philosophy. Sharon Street, a pretty prominent contemporary philosopher at NYU, explicitly characterizes her view as Humean Constructivism, which she contrasts with Kantian constructivism. (So it's not as if the only options for the constructivist are Humean, or relativist; Kantian constructivists are no relativists.) While she doesn't emphasize game theory/social equilibria, I do think it could fit pretty neatly into the stuff she *does* say.

I'd also insist that expressivists are missing from the chart, and I think they're significant enough that it's a big gap. While they're intellectual descendants of emotivists, in my view they don't inherit the vulnerabilities you rightly object to here. (They will say that moral claims are true or false, and that's an important part of how they deal with the Frege-Geach problem, though they'll have a distinctive understanding of what they're doing in so saying.) I pick the nits since I'm sympathetic both to expressivism and to the substantive picture you lay out here, and it's not at all clear to me that there's any tension in adopting expressivism as your basic account of what we're doing when we endorse fundamental moral principles, but also endorsing the game theory/social equilibria story as a causal/historical account of *which* fundamental moral principles we find attractive. I don't see any conflict.

So I think that the best place to go if you are attracted to Humean constructivism is not modern game theory, but in fact, another 18th century source: Adam Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments.

Hume is the OG, but Smith is the genius in the next generation who works it all out fully and in the most convincing way. For me, the TMS is the single greatest work in the history of moral philosophy. But if you think Hume is unfairly neglected, well...!

There are no real shortcuts into TMS, and it is a challenging book. But my God, it's rewarding. However, if I was to try and convince you, perhaps you could start here? :)

https://www.paulsagar.com/_files/ugd/ec3ee6_daf5b69e4db3401f84b3c14228879856.pdf