Is morality relative?

And if so to what extent

In this series of posts, I tackle the big question of fairness and morality: what it is and where our moral sense comes from. In the previous post, I argued that viewing morality as arising from social conventions does not mean that “anything goes”, or that moral rules have no meaning in the sense that they can simply be ignored. Here, I discuss another criticism: the fact that morality becomes relative.

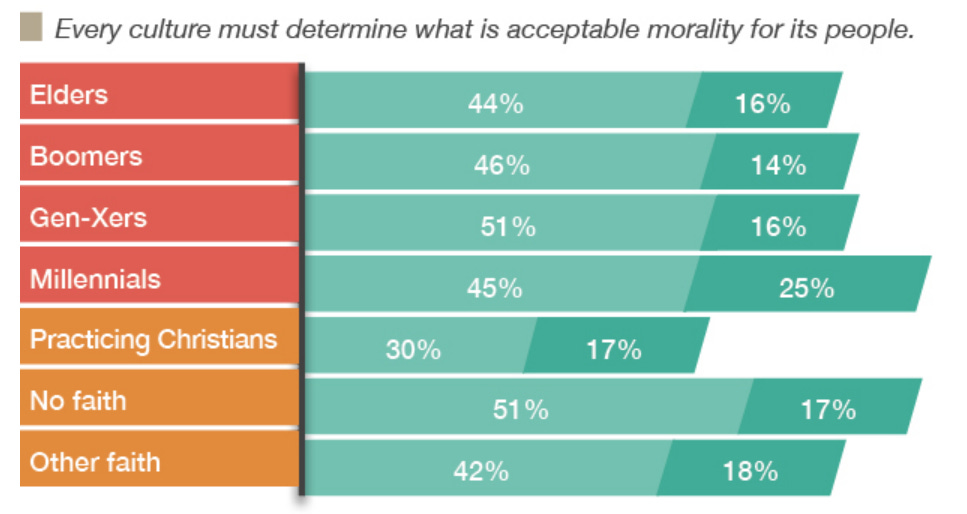

In a 2015 US poll, 65% of American adults agreed that “every culture must determine what is acceptable morality for its people.”1 And in a 2023 survey, 60% of “Gen Z” respondents agreed with the idea that what is morally right or wrong depends on what an individual believes.2

In academia, this view is quite prevalent in some parts of the social sciences, like anthropology. In 1887, Franz Boas, one of the founders of the discipline, wrote in the journal Science:

It is my opinion that the main object of ethnological collections should be the dissemination of the fact that civilization is not something absolute, but that it is relative, and that our ideas and conceptions are true only so far as our civilization goes. — Boas (1887)

I have argued that morality emerges from social conventions and that a society’s moral system can be seen as a social contract, implicitly agreed upon by all to coordinate and cooperate. This view is often labelled Humean constructivism, as it was first put forward by Hume. Its proponents, like Robert Sugden and Ken Binmore, also use the label contractarian, since these social conventions can be described as a social contract, implicitly agreed upon by all.3

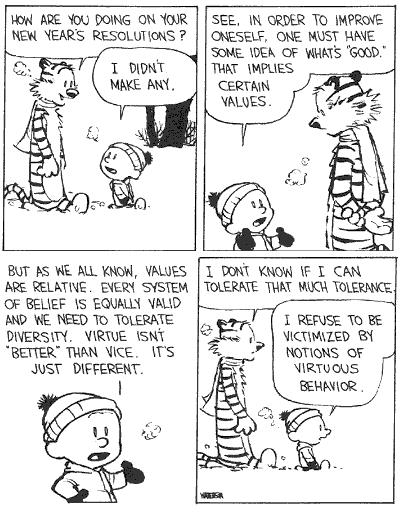

In this post, I address a criticism often levelled at this approach: it is “relativist”. With this term come accusations like these: If morality is just conventional, isn’t it the case that some societies can land on conventions we would find abhorrent, like infanticide, slavery, or genocide? In that case, would we not just have to accept these practices as fine?

The point I make here is that contractarianism is relativist in the technical sense used in metaethics, but not in the way the term is usually understood in everyday debate.

What “relative” means here

In metaethics, the branch of philosophy studying the foundations of moral claims, relativism is defined as the belief that there is no absolute moral truth. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines this viewpoint as:

The truth or falsity of moral judgments, or their justification, is not absolute or universal, but is relative to the traditions, convictions, or practices of a group of persons.

Under this definition, it is clear that a contractarian view is relativist. In a contractarian position, moral claims can be true or false, but only within a given moral system, a specific social contract. As a result, a moral claim that is true in one moral code can be false in another.4

Philosophers usually do not like moral relativism.5 To be frank, I do not like the term either because it is too often understood as meaning some sort of nihilism. The contractarian approach focuses on explaining the reality of moral rules and moral practices as part of a social contract, not on denying any relevance to moral considerations.

Can we condemn slavery/infanticide? Yes, in three coherent ways

There are many strands of moral philosophy that can be described as “relativist”. For some of them, which I would label “radical relativism”, different cultures cannot be compared in any way.6 This conclusion is not one that follows from the contractarian perspective I am presenting.

From within our own moral preferences

The contractarian position implies that there is no higher moral ground outside societies upon which we can stand to judge them, but it does not mean we are not entitled to our own preferences. Binmore, who, unlike me, is happy to defend the term relativism, says about it:

Moral relativism does indeed deny that it makes sense to say that one social contract is better than another in some absolute sense. But moral relativists nevertheless have their own opinions about the kinds of social contract they think desirable — Binmore (1998)

Nothing prevents us from liking or disliking another country’s practices based on our own moral preferences. Some of our fundamental moral preferences might have been shaped by evolution and be universal across cultures, while others are culturally acquired via education and socialisation.7

From an international social contract

Some (limited) order exists at the international level. In their interactions, countries follow norms that are both implicit (e.g. diplomatic usage) and explicit (e.g. international law established in treaties). These rules create a meta-normative system. While this normative system is largely silent on how countries handle matters within their borders, it does impose some constraints on practices that many states have come to view as among the most abhorrent.

Genocide is explicitly prohibited by the 1948 Genocide Convention of the United Nations, which states that it is “a crime under international law” and obliges states to prevent and punish it. The International Criminal Court has jurisdiction over genocide under the Rome Statute.

Slavery is prohibited under the 1926 Slavery Convention and the 1956 Supplementary Convention, which commit states to abolish slavery and suppress slavery-like institutions and practices.

Infanticide: International law does not use the term “infanticide”, but it protects children’s right to life. For example, the Convention on the Rights of the Child recognises every child’s “inherent right to life” and requires states to ensure the child’s survival and development.

It is important not to overstate the meaning of these international rules. International law is too often presented as an absolute yardstick of right and wrong. Instead, it is again a convention (between states). And this convention works only to the extent that the balance of states’ incentives limits infringements. A state willing to violate these rules and willing to face the negative consequences can do so.8

By outcomes and stability

Perhaps most importantly, different social contracts can be compared in terms of their practical consequences. Social contracts’ function is to regulate cooperation and conflict between members of society. Efficient moral systems can induce higher levels of cooperation and therefore higher welfare in society.

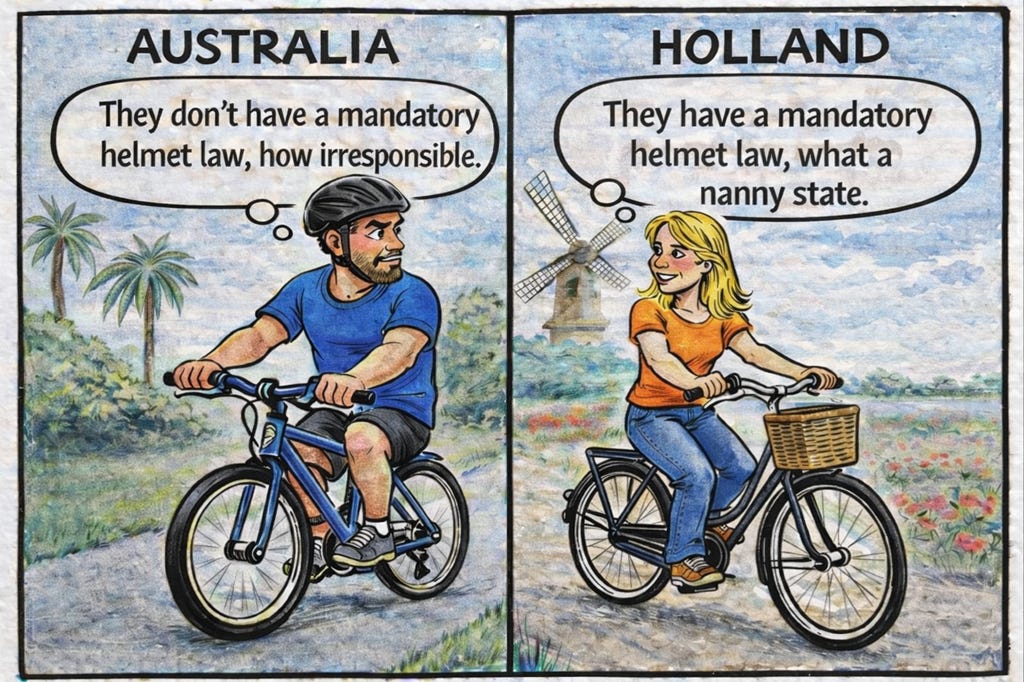

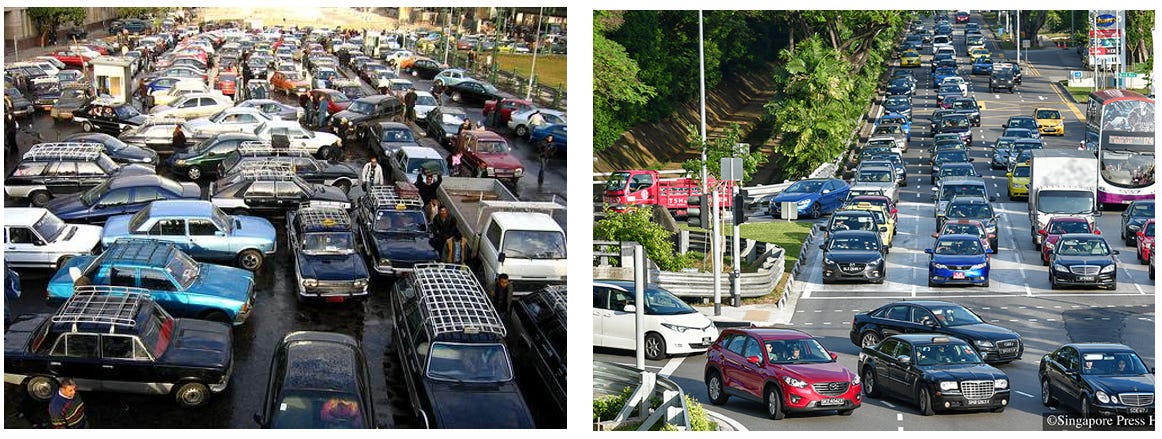

It is perfectly reasonable to compare moral norms to the extent that some can lead to better social outcomes than others. Consider, for instance, the driving rules in Singapore and Cairo. These rules are both formal (likely fairly similar in both countries) and informal, in particular, what people consider acceptable to do (how often to honk, how much to respect the rules, how gracious to be). Singapore driving norms seem unambiguously better, in the sense that they appear to be associated with less driving chaos and better driving times.9

Once again, this aspect should not be overstated. First, such a criticism is not made from a higher moral high ground, and it does not assume that “efficient cooperation” is a good that should be pursued as an absolute moral goal. Instead, this criticism can be made from the point of view of the society concerned. Saying that the Singapore equilibrium is better than the Cairo equilibrium is saying that Cairo dwellers would themselves prefer to live with the Singapore equilibrium if they could switch to it as a society. Second, efficiency does not a priori preclude some practices in other societies that we find abhorrent in ours.10

How moral realists use “relativism” as slander

Moral realists, lacking a settled account of what absolute moral truths are and how we would know them, often resort to dismissing scepticism towards moral realism with what Binmore calls “emotive slander”. They use the label “relativism” to accuse non-moral realists of supporting a vision of reality where things we find abhorrent, like infanticide and slavery, are fine.

I have been accused of holding that pedophiles are justified in disregarding the law when pursuing their claim that prepubic sex is good for children. Similarly, relativists supposedly see nothing wrong in keeping slaves or wife-beating, since both activities have been endorsed as morally sound by past societies. — Binmore (1998)

The contractarian view is not that these things are OK. It is that there is no external moral rule book that conveniently provides us with the rules on how to behave to be Right or to do Good. Instead, we hold our morality in our own hands. As social groups, we have to agree on how to work with each other to facilitate cooperation and resolve conflicts. Morality is fundamentally about adopting a social contract, an agreement about how to organise social life. “Correct” social rules are not written in the fabric of the universe; we are on our own and in charge of our own rules.11

What the “relativism” in contractarianism is not

I have indicated that the contractarian approach is relativist in the technical sense used in metaethics. However, the word “relativism” is loaded with different meanings. It is useful to make clear what the versions of this term that contractarianism does not endorse.

Not subjectivism

A frequent interpretation of moral relativism is subjectivism, which can be summarised by the idea that everyone has his or her own truths. This idea does not reflect how morality works in real life, and for a contractarian, it is logically inconsistent.

[M]oral subjectivism is absurd because it overlooks the fact that moral rules evolved to help human beings coordinate their behavior. But successful coordination depends on everybody operating the same moral rules. If everybody in a society made up their own standards, there wouldn’t be any point in having moral rules at all. — Binmore (2005)

If moral views were just things that can differ in each of our heads, how would they work? Why would Alice care when Bob tells her she is wrong, according to his own principles of morality? Why should she grant this claim more significance than if Bob were pointing out that he prefers chocolate ice cream, contrary to her choice of vanilla flavour?

Not relative to “culture”

A slight variant of subjectivism is that morality is just a characterisation of a culture in the sense that people from different cultures have different ideas.

The view of morality as convention requires more than morality being about ideas in people’s minds: moral rules must be equilibria in social games played in a given social setting. This requirement means that if people from different cultures live together in a given society, each cultural group cannot have its own morality. The idea that cultures can simply coexist side by side with their moral code in a society is as misguided as the subjectivist idea that people can live side by side with their idiosyncratic moral views.

Let’s take a simple example. Consider a society in which two groups have internalised different cultural expectations about queues. One culture treats strict queueing as a basic rule of fair access: first come, first served. The other group treats the “queue” as more of a loose signal, with access negotiated through persistence and a bit of elbow-work. If you queue diligently among people in that group, you may find that they move ahead of you without treating this as a serious breach of conduct.12

Imagine that, because cultures are said to be “equal” and not assessable from outside, members of the second culture are permitted to ignore the queue when interacting with everyone else. This would not lead to the peaceful coexistence of two norms in the same shared space. It would more likely unravel the queueing equilibrium altogether: once compliance is no longer common knowledge, people in the first culture lose the incentive to keep queuing, and the institution stops doing its job.

Obviously, a society could not work if groups could have their own moral codes. A society requires an overarching moral system that regulates interactions between all members of society.13

Not all cultures are “equal”

Perhaps the most common version of relativism outside of academic philosophy is the idea that different cultures cannot be compared and judged from the point of view of other cultures. In practice, this goes with the idea that each culture is equal and that every culture should be respected. This question has taken a political aspect, with right-wing thinkers often praising Western culture and institutions as superior to the culture of some other countries, sometimes described as backward. In opposition to this view, some left-wing thinkers argue that all cultures are equally worthy of respect. This view is, perhaps understandably, often promoted in international bodies. The UNESCO Declaration on Cultural Policies (1982) stated, for instance, that

The equality and dignity of all cultures must be recognized, as must the right of each people and cultural community to affirm and preserve its cultural identity and have it respected by others.

The idea that all cultures are equal in worth is, in fact, unfounded in a contractarian perspective. While using the term “relativist” for his position, this is what Binmore says here:

The basic misunderstanding is that traditionalists think that to refuse to label a Society as Wrong or Bad is to say that all societies are equally Right or Good. But a relativist finds no more meaning in the claim that two societies are equally Good than he does in the claim that one is Better than the other. — Binmore (1998)

And he adds:

[T]he wishy-washy liberal doctrine that all societies are equally meritorious receives no support from naturalism. — Binmore (1998)

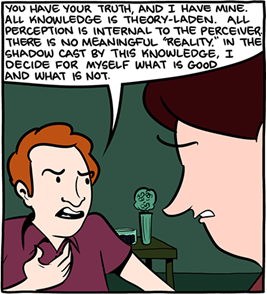

Not postmodernism

Finally, an important point to make is that saying that there is no absolute moral truth is not saying that there is no objective reality out there. The idea that refusing the absolute truths of moral claims is like rejecting the objectivity of reality is like saying that if one claims that there are no absolute rules of football written in the fabric of the universe—these rules being human conventions—one must be denying that the football pitch, the ball and the players really exist.

Contractarianism is therefore not a bedfellow of postmodernism and its often sceptical claims about the existence of universal truths that can be studied through reasoning and empirical observation.

Moral relativists believe that moral facts are true because they are generally held to be true within a particular culture. Postmodernists claim to believe that the same holds for all facts. A postmodernist must therefore be a moral relativist, but nothing says that a moral relativist must be a postmodernist. For example, I am as premodern as it is possible to be, but I am nevertheless a moral relativist. — Binmore (2005)

On that front, Binmore, I, and other contractarians are firmly on the side of rationalism. When considering postmodernism, whose wordplay often tiptoes around suggestions that the notion of external reality is a fallacy, I would use this famous view from Bertrand Russell:

This is one of those views which are so absurd that only very learned men could possibly adopt them. — Russell (1959)14

Reform

The fact that we can compare moral rules in terms of their outcomes and stability should make it clear that contractarianism does not prevent reform from happening. A big question about institutions is their ability to organise social cooperation successfully. It is clear that some institutions are more effective at this than others. In his book The Origins of Political Order, Francis Fukuyama describes this difference between institutions with “Denmark” being used as an example of having highly successful institutions.

The problem of creating modern political institutions has been described as the problem of “getting to Denmark;’ after the title of a paper written by two social scientists at the World Bank, Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock. For people in developed countries, “Denmark” is a mythical place that is known to have good political and economic institutions: it is stable, democratic, peaceful, prosperous, inclusive, and has extremely low levels of political corruption. Everyone would like to figure out how to transform Somalia, Haiti, Nigeria, Iraq, or Afghanistan into “Denmark,” and the international development community has long lists of presumed Denmark-like attributes that they are trying to help failed states achieve. — Fukuyama (2011)

It would be very reasonable for people living in countries that do not benefit from such a mix of institutions to argue in favour of political reform to get closer to “Denmark”. Here again, the argument is simply about the agreement of the people involved: proposing a move towards more effective institutions is proposing something people would have an interest in agreeing to. Binmore makes a plain case for this logic with the example of the switch of driving side in Sweden in 1967.

A real-life instance of the driving example may help. Sweden switched from driving on the left to driving on the right on September 1st, 1967. If I had been a Swede before this decision was made, I would have lent my voice to those advocating the change. Since relativists hold that it was wrong to drive on the right in Sweden before September 1st, 1967, and wrong to drive on the left afterwards, the words bad or wrong would have been useless to me when urging reform. It might have helped the cause to argue that driving on the left is intrinsically Bad or Wrong, but it would be intellectually dishonest for a relativist to take this line. Still less would I have argued that Swedish citizens should be left to make their own subjective judgments when choosing on which side of the road to drive. I would simply have argued that enough Swedes would benefit from driving on the same side of the road as the rest of continental Europe to make it worthwhile for us all joining together to get the reform adopted. — Binmore (2005)

So the key point is that calls for reform cannot be made from an appeal to morality, since the grounds for moral agreement are being negotiated in the process of reform.

[W]hat would it then mean to say that our current social contract is itself unfair? One must either accept that the relativism implicit in a naturalistic approach to ethics makes the question incoherent, or else abandon oneself to one or other of the traditional metaphysical notions of justice about which evolution cares not a whit. — Binmore (1998)

Nonetheless, in practice, moral language is often part of the bargaining and mobilisation that makes a new agreement possible. Requests for reform are bids to change the social contract at the societal level. Proponents can have strong moral feelings about it for two reasons: first, because of their deep moral preferences, and second, because of the moral preferences in the social group they belong to. An example of such positions is how opposition to slavery appeared from the start, within slave-owner societies in the West, as conflicting with deep feelings about respect for other humans and with the moral principles of religion.15

If successful, the rule change they defend will come to define what counts as right and wrong in society. There are only a few steps from thinking “it should be right/wrong” to feeling that “it is Right/Wrong”, especially when people have strong moral feelings about it.

Yet recognising that such appeals to external truths are ungrounded, and that we hold our morality in our own hands, can be liberating. It allows us to think more clearly and freely about how we want our society to be organised, instead of chasing the “Right” way in some mysterious metaphysical reality.

The present post has mostly been about defending the contractarian approach from the different accusations associated with the term relativism. A common argument put forward by moral realists is that it would lead us to accept practices that we find abhorrent, like slavery and infanticide. Given the strength of our moral feelings against such practices, it would be a very unappealing conclusion. However, as I have explained here, contractarians are not in any way bound to say that they find such practices fine. Like most people living today, they would typically prefer a world without them.

Having said that, it is worth pointing out that the moral realist position with this argument is much weaker than it seems. First, the fact that some conclusions might seem appalling is not a reason to reject a theory. Theories like heliocentrism or evolution seemed appalling to many when they were proposed, it did not make them wrong.16 The importance moral realists give to moral intuition as evidence is all the more dubious given that we can observe societies at present and in the past differing markedly in moral intuitions.17

Second, moral realists do not agree on a common theory of what absolute moral truths are and where they come from. They do not even agree on a common method to answer this question. If you take a naturalistic perspective, this persistent disagreement is not surprising. It has a simple explanation: moral realists are like ancient astronomers looking into epicycles to understand the movement of planets. They have a wrong starting assumption: there are some absolute moral principles out there for us to find.

This brings us back to the point I made earlier in this series of posts: because they aim to found morality in an absolute way, moral realists have to assume some skyhook at some point, to found their theory of morality on an “unconditional ought”: “I must do good because something is morally good and must be done”, full stop. This assumption that some abstract, immaterial principle has some kind of force on material beings like us is strange and, as famously pointed out by John Mackie, unlike anything produced by scientific knowledge. The appeal of such an idea might be particularly prominent in societies with a Judeo-Christian heritage, where an all-powerful moralising God has shaped our moral intuitions for centuries.

The contractarian approach sidesteps this metaphysical difficulty and the use of skyhooks to found morality. Instead, it posits that morality arises from something grounded in reality: a social agreement about how to organise social interactions.

References

Binmore, K.G. (1998) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 2: Just Playing: Economic Learning and Social Evolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Binmore, K.G. (2005) Natural Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boardman, A.E., Greenberg, D.H., Vining, A.R. and Weimer, D.L. (2018) Cost-Benefit Analysis: Concepts and Practice. 5th edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boas, F. (1887) ‘Museums of Ethnology and Their Classification’, Science, 9(228), pp. 587–589.

Disraeli, B. (1864) Speech at the Oxford Diocesan Conference (25 November 1864), quoted in Monypenny, W.F. and Buckle, G.E. (1929) The Life of Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield, Vol. II: 1860–1881. London: John Murray.

Fukuyama, F. (2011) The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Gowans, C. (2021) ‘Moral Relativism’, in Zalta, E.N. (ed.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2021 Edition). Stanford, CA: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University (Accessed: 3 January 2026).

Harman, G. (1975) ‘Moral Relativism Defended’, The Philosophical Review, 84(1), pp. 3–22.

Holland, T. (2019) Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. London: Little, Brown.

Hrdy, S.B. (1999) Mother Nature: A History of Mothers, Infants, and Natural Selection. New York: Knopf.

Hume, D. (1751) An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals. London: A. Millar.

International Criminal Court (1998) Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Rome, 17 July 1998 (entered into force 1 July 2002).

League of Nations (1926) Slavery Convention. Geneva, 25 September 1926 (entered into force 9 March 1927).

Mackie, J.L. (1977) Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

MacCulloch, D. (2009) A History of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. London: Allen Lane.

Melanchthon, P. (1549) Initia doctrinae physicae dictata in academia Vuitebergensi. Wittenberg: Johann Lufft.

Pritchett, L. and Woolcock, M. (2004) ‘Solutions when the solution is the problem: Arraying the disarray in development’, World Development, 32(2), pp. 191–212.

Russell, B. (1959) ‘Face to Face’ (television interview with John Freeman), BBC Television, 4 March.

UNESCO (1982) Mexico City Declaration on Cultural Policies (World Conference on Cultural Policies, Mexico City, 26 July–6 August 1982). Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations (1948) Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. New York: United Nations, 9 December 1948 (entered into force 12 January 1951).

United Nations (1956) Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery. Geneva: United Nations, 7 September 1956 (entered into force 30 April 1957).

United Nations (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York: United Nations, 20 November 1989 (entered into force 2 September 1990).

Williams, E. (1944) Capitalism and Slavery. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

https://www.barna.com/research/the-end-of-absolutes-americas-new-moral-code/

https://www.barna.com/research/gen-z-2024/

For the philosopher reader: not every contractarian view is Humean (assuming that morality comes from social conventions) and not all Humean views are contractarian.

Note also that the term “contractarian” is different from “contractualist”, usually associated with philosophers like Scanlon and Rawls. These authors still land on a moral realist position, assuming that reasonable people would agree on the right rules of morality.

In the same way, touching the ball with your hand is wrong in association football but fine in basketball.

Binmore states about this:

[M]oral relativism remains the big turn-off for most modern philosophers. — Binmore (2005)

The idea that different moral systems are incommensurable is, for instance, supported by Harman (1975).

Where do our moral preferences come from? Binmore makes a useful distinction between three types of time scales.

The short run, where moral preferences are stable. This time scale is measured in hours. It is the scale of our daily interactions.

The medium run, where moral preferences can change by cultural evolution. This time scale is measured in years. It is the scale where we observe societies’ moral rules changing over time, and with them the moral preferences of people socialised in that specific society.

The long run, where moral preferences can change by biological evolution. This time scale is measured in generations. It is the scale where moral preferences can become encoded in our DNA via gene culture co-evolution (genes best suited to generate behaviour adapted to a given culture are selected).

The long-run perspective can explain why it seems that humans share some universal views about morality. This view is compatible with Hume’s suggestion that there are some universal aspects to moral feelings:

While the human heart is compounded of the same elements as at present, it will never be wholly indifferent to public good, nor entirely unaffected with the tendency of characters and manners. And though this affection of humanity may not generally be esteemed so strong as vanity or ambition, yet, being common to all men, it can alone be the foundation of morals, or of any-general system of blame or praise. — Hume (1751).

Binmore thinks, for instance, that the Golden Rule might be a universal deep preference to help us interact cooperatively with others. The fact that our ancestors tended to live in more egalitarian societies than now might also have shaped some deep preferences for equality and freedom in us.

There are, therefore, possibly some universal moral intuitions or a universal way to think about moral problems which might offer a shared standpoint to judge any given society. For instance, our egalitarian preferences might give us an inclination to prefer societies with more freedom. I should stress, however, that saying this only means that there might be universally consensual views (everybody agrees with them) not that these views have some kind of absolute existence outside of people harbouring them. Furthermore, this universal aspect should not be exaggerated. The study of widely different cultures around the world and throughout history shows that our present moral intuitions are often very specific to the type of modern societies we are living in.

Like for Gyges’ story, there is nothing besides these rules and the sanctions for violating them that will move states to respect them. The community of states is only loosely organised, and the sanctions for violating the rules of the international order are often weakly enforced, in particular when the violation pertains to things happening within a country.

Technically, Binmore’s argument is about Pareto dominance, or in plain English, consensus: some societies’ rules are better because everybody is better off. Driving rules are better in Singapore than in Cairo for everybody. Economic and political rules are better in the US than in North Korea for everybody.

Often, reforms will not lead to improvements for everybody. However, if outcomes are better on average, one should be able to organise transfers for everybody to be better off. The challenge is for such transfers to be made for this improvement to be true in practice. Another solution is for a social contract to adopt reforms in a utilitarian way: a change in policy/practice is adopted whenever the gains are positive on average in society. This is basically the modus operandi of economists in their policy recommendations. If there are enough small policies with a small number of losers each time, then everybody in society can hope to be better in the long run without having to deal with the design and implementation of transfers (Boardman et al., 2018).

Such an approach breaks down when losses are large and might be recouped or when trust that one will benefit later erodes. The loss of faith of popular classes in globalisation can be read in this light as a loss of faith that these “on average positive” evolutions will in the end benefit them.

A contractarian can argue that this question might often invert the logic of our morality. If we find something abhorrent, it might be because it has been rejected from our social contract for its inefficiency. Cultural evolution, which through selection and imitation, would tend to select more efficient social contracts, has leached out practices that were either never efficient or that stopped being efficient when progress increased. For instance, historian Eric Williams famously argued in Capitalism and Slavery that British abolition aligned with shifting economic interests and the declining profitability of the West Indian plantation complex. Similarly, infanticide has been reported in societies where families faced extreme resource constraints and limited control over fertility (Hrdy 1999, Mother Nature). With contraception and higher living standards, such practices tend to become rarer.

Saying that we are in charge does not mean that we explicitly decide all these rules. Biological evolution has provided us with a moral sense that helps us play these social games by taking other people’s perspective, and cultural evolution has provided us with social conventions that have been selected over time for their ability to organise social interactions. It is similar to the fact that biological evolution gave us the ability to speak and cultural evolution gave us a specific language.

The point about cultural evolution leading to greater cooperation is supported by the idea of cultural group selection. Societies that had dysfunctional norms of cooperation lost out to those societies whose norms enabled them to leverage the gains from cooperation more efficiently.

The queueing equilibrium clearly has some social benefits. In Australia, which inherited a queueing culture from Britain, you can even sit down in an unorderly manner when arriving at the barber's to wait your turn. People waiting keep in mind the order of arrival and, if asked, point the barber to the next person whose turn is up. Such a system ensures some peace of mind for all. You do not have to be constantly checking when the barber has finished to lunge forward and avoid losing your turn.

One possibility is a single moral system used. For instance, migrants moving to a new country might have to accept the rules of the new country, even if those differ from their original culture.

Note that while the fact of belonging to a common society imposes a common morality, it does not mean that people have to agree on everything. There are many social settings with their own specific moral rules. A church congregation might follow different rules of propriety than a gay bar and coexist in the same society.

A key question in a society is what remit to give to subgroups to follow group-specific rules. At one end, one can think of a society rejecting any group-specific norm that would deviate from the whole society. At the other end, one can think of a kind of cultural federalism: different communities having their own moral code to manage conflict and cooperation within their own members, while general rules are used to regulate interactions between communities.

This is what happened in societies as diverse as the Ottoman Empire with its millet arrangements (recognised religious communities running their own institutions and courts for personal-status matters such as marriage, divorce, and inheritance), the Mughal Empire and its personal laws (a plural legal order where different religious communities often relied on their own norms, especially in family and inheritance matters, alongside imperial courts), and the Spanish Empire in the Americas with its Republic of Indians (a separate corporate jurisdiction for Indigenous communities, with local governance and elements of customary law for internal affairs, under overarching Crown authority).

Such a solution, however, might be unstable as the different moral codes of different groups might conflict and create social tensions. Another issue is how ascription to a community is decided. Does someone belong to a cultural group by birth, or can one change at will? Some people from a group who could fare better in another might be tempted to leave, leading to tensions.

The inconsistency of postmodern relativism is well illustrated by the fact that its proponents regularly manage to arrive at their meetings on time even though, as pointed out by John Moore:

[I]t will not help you to catch a train if you cannot believe the times in the timetable are true. — Moore (1996)

In the 15th century, Franciscan priests opposed slavery in the Canary Islands:

[They] spoke out strongly against enslaving native people who had converted to Christianity, and sometimes made a leap of imagination to oppose enslaving those who had not converted. — MacCulloch (2009)

Shortly after, Bartolomé de las Casas, a former colonial official and plantation owner, became a critic of the exploitation of natives in the New World.

[H]is insistence that native Americans were as rational beings as Spaniards, rather than inferior versions of humanity naturally fitted for slavery, sufficiently impressed the Emperor Charles V that debates were staged at the imperial Spanish capital at Valladolid on the morality of colonization (with inconclusive results). — MacCulloch (2009)

Philipp Melanchthon, a German Protestant reformer, best known as Martin Luther’s principal collaborator, declared about heliocentrism:

The eyes are witnesses that the heavens revolve in the space of twenty-four hours. But certain men, either from the love of novelty, or to make a display of ingenuity, have concluded that the earth moves; and they maintain that neither the eighth sphere nor the sun revolves. — Melanchthon (1549)

Later, the politician Benjamin Disraeli declared about Darwin’s theory of evolution:

The question is this—is a man an ape or an angel? My lord, I am on the side of the angel. I repudiate with indignation and abhorrence those views. I believe they are foreign to the conscience of humanity; and I will say more than that, even in the strictest intellectual point of view, I believe the severest metaphysical analysis is opposed to that conclusion.— Disraeli (1864)

In his book Dominion, the author Tom Holland stresses, for instance, how the moral intuitions of ancient societies were foreign to ours about practices such as slavery and infanticide:

The more years I spent immersed in the study of classical antiquity, so the more alien I increasingly found it. The values of Leonidas, whose people had practised a peculiarly murderous form of eugenics and trained their young to kill uppity Untermenschen by night, were nothing that I recognised as my own; nor were those of Caesar, who was reported to have killed a million Gauls, and enslaved a million more. It was not just the extremes of callousness that unsettled me, but the complete lack of any sense that the poor or the weak might have the slightest intrinsic value. — Holland (2019)

Fun fact: the switch to driving on the right in Sweden 1967 was preceded by a non-binding referendum in 1955 where more than 80% voted against. Parliament still pushed it through. Not sure what that says about contractarianism...

It’s funny how (many, not all) moral realists misrepresent anti-realism or relativism so often (like Binmore being accused of horrendous claims). You’d think person believing that lying is bad in some ‘objective’ way would be less prone to such propagandistic tactics.