A defence of morality as respect for a social contract

The absence of absolute moral truths does not mean that "anything is permitted"

In this series of posts, I tackle the big question of fairness and morality: what it is and where our moral sense comes from. In the previous post, I presented how we can understand morality without absolute moral truths as conventional rules that help organise human coordination and cooperation in social games. Here, I discuss the implications of this explanation for the meaning of moral claims.

A poll of modern philosophers suggests that a majority of them are moral realists.1 They assume that morality is objective in the sense that there are moral truths that exist independently of what people might think about them. This view is, interestingly, at odds with the origin of the term “morality” which points to social conventions.

[E]tymologically, the term “moral” comes from the Latin mos, which means custom or habit, and it is a translation of the Greek ethos, which means roughly the same thing, and is the origin of the term “ethics”. — Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2019)

In line with this etymological origin, I argue that the best explanation of morality is that it emerged to regulate cooperation and coordination in social interactions, and that moral systems are social conventions. This naturalistic approach starts from the factual observation that people have partially but not fully aligned interests, leading to social interactions that mix cooperation and conflict.

This view eliminates the need to posit unobserved moral truths for moral rules to mean something. Moral rules can be understood as commonly agreed rules of social interaction among members of society. These rules feel deep and fundamental because they govern the most important game we play: the Game of Life. The idea that moral rules in a society are agreed upon is often reflected in the use of the term “social contract” to describe them. People learn these rules through education and socialisation.

In this post, I address criticisms levelled at this view of morality as the reflection of a social contract.

The guilt trap

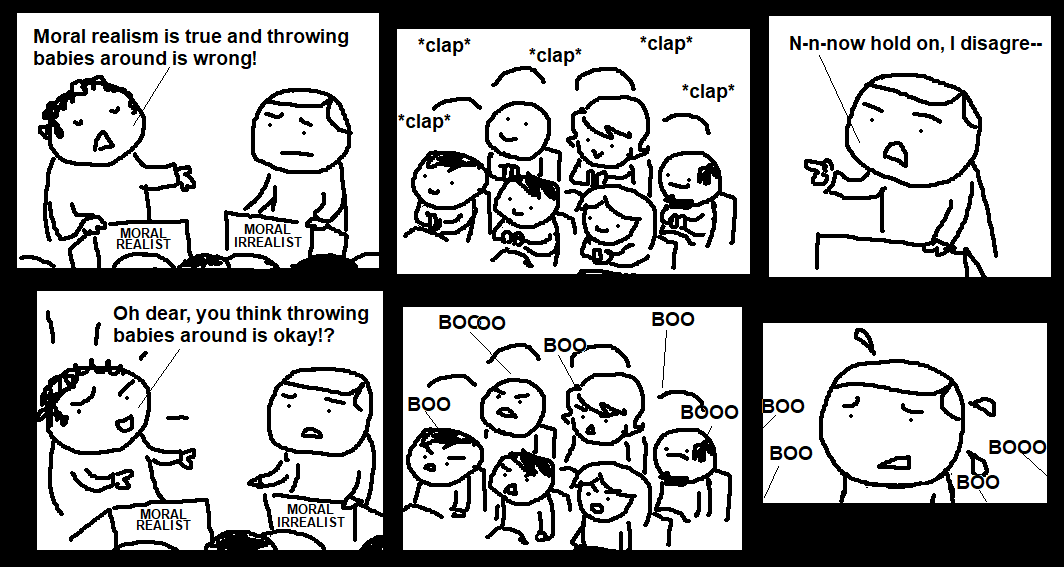

One often hears the suggestion that if morality is only conventional, it is meaningless.2 We are then told that if moral claims have no meaning, anything goes. Some of the worst things we can think of—like killing innocent people—must be “fine” and nothing compels criminals to behave well.

The leap from “conventional” to “anything goes” is a mistake, and I’ll explain why in the next section. But I’ll start by criticising this style of counterargument, which I’ll label a guilt trap. It is a trap because it is another version of the Santa Claus fallacy. It is saying something like: “do you realise the awful implications of your beliefs”?

In fact, even if a theory were to lead us to very distasteful conclusions, that would not be a reason to reject it. Suppose that—ghastly horror—we were to find that our home, Earth, is not the centre of the universe, but just a tiny dot rotating around an average star, somewhat on the skirt of a galaxy comprised of about 100 billion stars, itself one among billions of galaxies. Too bad. Reality is not determined by our preferences. A Humean constructivist can therefore stand firm on rejecting the guilt trap because it is not a good argument to begin with.

But because the human brain is designed to argue in favour of our preferences, it might nonetheless be a useful rhetorical move for the Humean constructivist to point out that nothing fundamentally ghastly should be expected from this approach. The goal of Humean constructivism is to explain morality—practices and beliefs—as it is observed in real life. Hence, a Humean constructivist is more likely to explain why our current moral practices often make sense than to advocate throwing them away in favour of views we find abhorrent.3

Morality as the respect of a social contract

Moral systems as social contracts

The first point to make is that saying there are no absolute moral truths is not the same as saying moral claims are meaningless. A contract sets rules defining rights and duties between those who sign it. The rules created by a contract do not come from “out there”. They arise from an agreement between different parties. Saying that morality emerges from commonly agreed rules—conventions—about how to behave in society does not imply that these rules are meaningless or can be ignored at will.

Imagine Alice and Bob start playing tennis. At some point, Alice hits a perfectly good forehand that lands 1 m within the court. Bob yells “out” and claims the point. Alice is entitled, by the rules of the game, to say “you are wrong, Bob, you lost the point”. This claim is not “meaningless”. It is true, given the rules of tennis.

We can agree that the rules of tennis are conventional. They are neither written into the fabric of the universe nor implied by the rules of pure logic. Does it follow that, because they are conventional, Bob can simply ignore them? The answer is simple and non-mysterious: it is a matter of fact that Bob might choose to ignore the rules and claim he won the point even though he did not. But if he does so, he violates the implicit understanding he had with Alice that he would play fair, that is, play by the commonly agreed rules. Faced with an outright disrespect of the rules, Alice is likely to fire back: “fine, I am not playing with you anymore”. The rules of tennis are a social contract between players. Bob cannot violate this contract and expect Alice to continue playing while ignoring his violations.

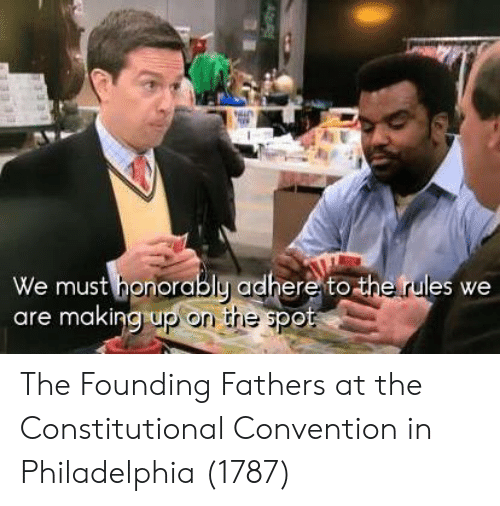

The word social contract can seem grand. Past philosophers sometimes implied, like Hobbes, that there might have been a time when people literally sat down to agree on a social contract. These stories are clearly fictitious. In his discussion of the origin of state institutions, Francis Fukuyama points out that early states pretty much never formed that way:

We might label this the Hobbesean fallacy: the idea that human beings were primordially individualistic and that they entered into society at a later stage in their development only as a result of a rational calculation that social cooperation was the best way for them to achieve their individual ends. — Fukuyama (2011)

Such fairy tales about social contracts are not necessary. A social contract can be understood as a commonly agreed understanding of how things should be done, and what would count as a breach of acceptable behaviour in society. To be clear about how he uses this expression, Binmore writes:

This section has identified a social contract with an implicit self-policing agreement between members of society to coordinate on a particular equilibrium in the game of life. Some apology is appropriate for those who find this terminology misleading. […] Words other than contract—such as compact, covenant, concordat, custom, or convention—might better convey the intention that nobody is to be imagined to have signed a binding document or to be subject to pre-existing moral commitments. Perhaps the best alternative term would be “social consensus”. This does not even carry the connotation that those party to it are necessarily aware of the fact. — Binmore (1994, emphasis mine)

If morality emerges from conventions, in what sense “ought” we to abide by moral rules? The answer is that we ought to abide by moral rules to be able to continue to play in social games with others, and to remain accepted as a player by them. If we violate that social contract, we lose our right—as defined by the social contract—to be treated as a rule-abiding player, and we risk a range of sanctions. In the extreme, we might be thrown out of the social game entirely, ending up in prison or worse.4

People sometimes react to this explanation by saying: this is not a proper “ought”. This claim tends to take two forms. First, there are rules you really ought to follow, even if you would face no social sanctions for not doing so. Second, there are things that are really bad, whatever people think about them, like “killing innocent people”.

The ring of Gyges

Let’s first address the idea that morality must imply a duty to do something beyond the costs and benefits set out in the social contract. This question was already discussed in Plato’s Republic, where Glaucon counters Socrates’ idealism with a story about what happens when we gain impunity. In the story, a shepherd named Gyges finds a ring that lets him become invisible at will. Once he realises he can act without being seen, he uses the ring to enter the palace, seduce the queen, kill the king, and take the throne.

Glaucon concludes:

[E]very man, when he supposes himself to have the power to do wrong, does wrong.

For Glaucon, we follow moral rules only because we have an interest in doing so. Remove the incentives to behave well, and we would stop doing so. This view is not necessarily in line with our intuitions. Plato uses Glaucon’s view to criticise it and argue that there is more to being moral: morality comes from within us, and being moral is necessary to be at peace with oneself and happy.

From a Humean constructivist perspective, Glaucon’s argument seems, unfortunately, somewhat sound. In the end, a social contract works only if it creates incentives for people to follow it. Binmore even points out that assuming we have a moral sense that reliably drives us to behave against our interest would conflict with the logic of evolution:

[I]f the morality of everyday life required people to take actions that made them less fit, how could it have evolved? […] one of the achievements of modern social psychology has been to expose the gap that lies between how we like to think of ourselves and the reality of what we actually are. […] realism requires that we take the same attitude to how society actually works as Oliver Cromwell took to his appearance. He too would have liked to look better, but he nevertheless insisted on being painted “warts and all”. — Binmore (1998)

What is the meaning of words like right or wrong and ought

How should we think of Gyges’ actions, if morality is seen as the reflection of a social contract?

First, it is perfectly coherent to say that what Gyges is doing is “wrong”, given the social contract of his society. Rules of social contracts do not say “don’t do that except if nobody is watching.” Rules are meant to be obeyed, whether there are observers or not. It is unlikely that the excuse “Sorry, officer, I thought nobody was watching” has ever been successful in evading a speeding ticket.

Second, it is coherent to say that Gyges “ought” to avoid doing all the bad things he does. He ought to play by the rules of the social contract if he wants to remain entitled to be treated as a good social partner by other people. If he behaves badly and he is found out, for instance, if he drops his ring, he would face the consequences.

But wait, you might say: “what if there is a 0% chance that he would be found out, and therefore no reason for him not to behave badly?” Here, the Humean constructivist resists the pressure to invent a skyhook: a moral duty that exists above and beyond the social contract and somehow binds Gyges to behave well in all circumstances. If there are absolutely no penalties for violating the rules of the social contract, there is no additional force, external to the social contract, that would give Gyges an injunction to respect it.

Note that this does not mean Gyges is permitted by moral rules to behave badly. The observation that motorists can (and sometimes do) speed when there is no police around does not mean that this action is condoned by the driving code.

Explaining the role of moral intuitions in social interactions

These answers, while very clear and coherent, face the challenge of our moral intuitions: we feel that cheating when unobserved is bad. Here, however, we should not treat these intuitions as a window into moral truth. A naturalistic approach should instead explain why these intuitions exist and why they take the form they do.5 The answer is that evolution endowed us with a moral sense that helps us play social games well. As I said in the previous post:

Our moral sense, shaped by eons of evolution, is designed to provide us with emotions that help us play the Game of Life successfully. Any deviation from the moral code puts us at risk of future sanctions: blame, ostracisation, and even, in some cases, violence. Our moral emotions track the costs of deviations and bring them back into our present. They embed this shadow of the future in our daily experience.6

These moral intuitions are also designed to help us assess others’ behaviour and detect violations, subtle or blatant, of the social contract. In Gyges’ case, our intuitions tell us that what he did is wrong. A social contract works to the extent that deviations are sanctioned. Members of society are required by the social contract to sanction violations of that social contract. Not doing so is a breach of the contract in the same way as not reporting a crime can be itself a crime (“misprision of felony”). It is therefore clear that upon hearing Gyges’ story, listeners like us ought to form the kind of negative moral judgement that would justify punishing him if he were found out.

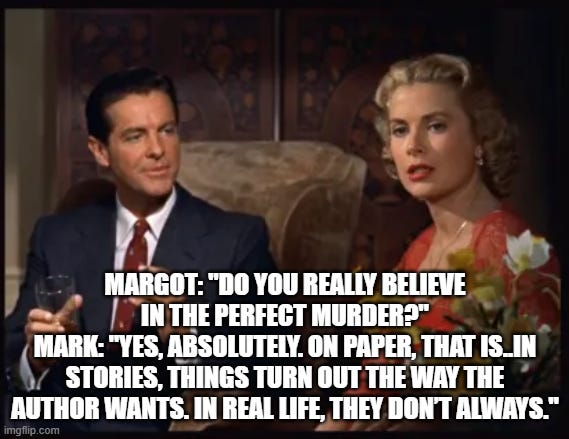

What about Gyges’ feelings? Even though Gyges might face 0% risk of being found, he might nonetheless experience moral feelings about his actions: a sense of duty not to behave badly, and guilt for thinking about or doing bad things. Here, again, the answer is not mysterious. These feelings evolved to track the possible risk of being found out and the future costs involved. Even if we face a situation of total impunity, it is reasonable for such feelings to be triggered, because situations with truly 0% risk do not really exist in real life. Even the culprit in Hitchcock’s story of a “perfect murder” in Dial M for Murder ends up being arrested. Hence, we should not be surprised that our moral emotions ring alarm bells, even when it seems that no risk of being found out exists.7

Being mindful of the deceptive appeal of the term social contract

Another problem generated by our moral sense is that the term “social contract” is itself loaded. We have a duty to respect a contract in society, because every specific contract is embedded in the overarching rules of the social contract.8 There is, however, nothing above society that sustains the social contract.

The term social contract might therefore be deceptively appealing. Our intuitions may find it more palatable than the term convention. I would, however, be slightly disingenuous if I leveraged those positive intuitions to make the idea of morality as a social contract sound more convincing.

I shall emphatically not argue that members of society have an a priori obligation or duty to honor the social contract. On the contrary, it will be argued that the only viable candidates for a social contract are those agreements, implicit or explicit, that police themselves. […] — Binmore (1994, emphasis in the original)

The role of trade-offs in morality

Note that these emotions do not need to feel to us like they are tracking risk return trade-offs. We can feel strongly motivated by such feelings, and some people experience them more than others.9 In other words, the fact that our moral sense tracks risk-return trade-offs is an ultimate explanation of moral behaviour, but we often experience moral judgements as driven by strong feelings and principles that seem devoid of calculation. These feelings are the proximate explanation of our moral behaviour.10

Having said that, it would be naive to ignore trade-offs. We would like to think we would act morally in all circumstances, but the statement “The surprising thing is not that every man has his price, but how low it is,” commonly attributed to Napoleon, bites because for every Schindler willing to sacrifice his interests for moral principles, there were many more Eichmann who followed wherever institutional carrots and sticks led them.11

my hero in the Republic [is] Plato’s brother, Glaucon—who gets short shrift from Socrates for putting a view close to the social contract ideas defended in this book. I think that a modern Glaucon would be agreeing with me that fairness norms evolved to select one of the many ways to balance power in a group. — Binmore (2005)

The Humean constructivist answer to the Ring of Gyges challenge

We can therefore summarise a Humean constructivist answer to the challenge of the ring of Gyges as follows:

We can say that Gyges was “wrong” given the social contract.

According to that social contract, Gyges “ought” not to violate its rules. But a social contract that does not attach appropriate incentives to its rules will fail to be followed. If a social contract has appropriate incentives, then the rules of the social contract align with Gyges’ interests: not only should he follow them from the social contract perspective, but he also should follow them from the perspective of his own interests.

If Gyges violates the social contract thanks to his impunity, other members of society will have strong moral feelings condemning it.

Gyges might also have negative moral feelings about it (though these feelings might erode with repeated experience of impunity).

Not “anything goes”

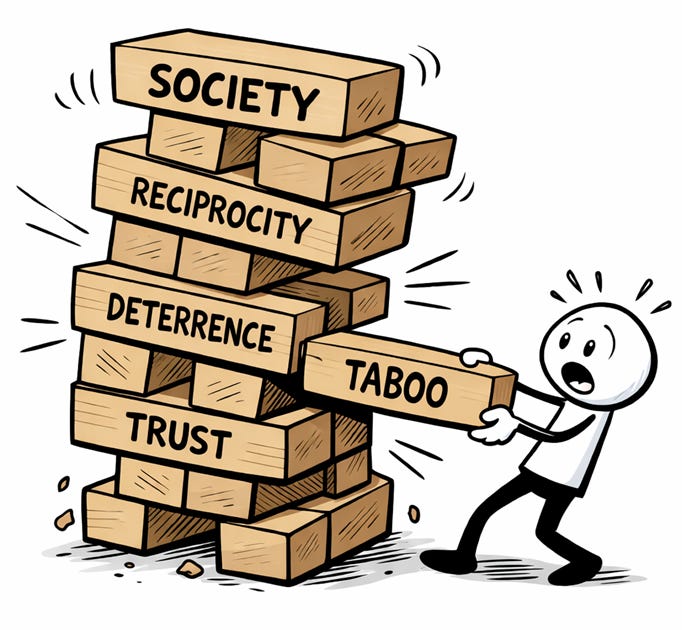

It is easy to misread the claim that moral norms are man-made (or socially constructed) as implying that anything goes. To start with, moral norms need to be respected for society to work. A society where civility and trust disappear breaks down.

In addition, moral norms cannot take any possible shape or form. The logic of strategic interactions imposes constraints on them.

Not everything can work as a social contract

Saying that because moral norms are socially constructed, they can be anything is a bit like saying that because buildings are man-made, they can take any shape. Buildings can take many shapes, but to withstand the test of time they must respect the laws of physics. It is exactly the same for moral norms. It is obvious that they differ widely across times and places, but for them to work over long periods, they need to respect the “laws” of social interaction, so to speak. In other words, they must be compatible with the patterns of behaviour that emerge in human societies, given that individuals have partially but incompletely aligned incentives.

The idea that moral and fairness norms are equilibria of social games has a key implication. If they remain stable and respected, it is not because people are brainwashed and mindlessly obey imposed rules. Instead, social norms are stable because they are self-enforcing: everybody has an interest in following them when everybody else follows them.

Consider driving on the road in a country like the USA. Why is the rule “everybody drives on the right side of the road” respected by nearly everybody in society? One might be tempted to say it is because it is illegal not to do so. But there are many countries where it is illegal to do various things, and many people nonetheless treat the law as a flexible instruction rather than a strict rule. The real reason almost everybody drives on the right in the US is that it would not pay to drive on the left. You would most often not arrive earlier, you would risk an accident, and because nobody else does it, you would likely attract negative judgment from people around you.

Among all the possible moral codes one could conceive, only a tiny proportion are equilibria. The rule “everybody drives on the right” is not the only solution. In several countries, like the UK or Australia, the rule “everybody drives on the left” is used instead. But no country has adopted in its official driving code rules like “drive on the side you fancy” or “cars drive on the left and trucks on the right”. There are good reasons for these absences. These alternatives are not solutions to the driving game.12 Any country with such rules would find not only that they lead to bad outcomes but also that people end up not respecting them. Conventions to drive on the left or on the right would emerge anyway. Historically, for example, the convention to keep left on the road emerged in Britain as a practice long before it was formally written into national traffic law.13

Moral, legal and ethical systems are conventions, but they are not arbitrary: they are constrained by the structure of conflict and cooperation in society.

A lot of the things we find abhorrent generate such feelings for good reasons

We can expect that moral systems that survive the test of time will encode concerns for participants’ lives and physical integrity. An argument of the type “killing random people is wrong, therefore there are absolute moral truths” mistakes our proximate moral feelings—attuned to the fact that modern societies ban random killings—for evidence that there is an absolute truth “out there” about it.

A Humean constructivist, and in particular Binmore, points out that if our current rules are the way they are, it is typically because they help sustain the way our society works. In liberal democratic countries, moral systems form a social contract well-suited to support large-scale cooperation. Therefore, in addition to the fact that Humean constructivists typically share the same negative moral feelings as everybody else about ideas such as allowing random killings, they also have an additional reason to reject such radical suggestions: they would likely tear the fabric of society.14

Mainstream ethical philosophy is lost in conceptual mazes because it takes our moral intuitions at face value, as if they pointed to something “out there” that justifies our moral stances. We “ought” to do this or that because it is right or good in an absolute sense. Moral intuitions are, however, the tail that wags the dog. Starting from them to build an understanding of morality treats the proximate psychological mechanisms that help humans navigate cooperative social interactions as a primary source of insight into morality, instead of looking at the ultimate causes of morality: the logic of human cooperation, which shaped these intuitions.

Saying morality arises from social conventions, and that we can think of moral systems as a social contract, often raises the concern that nihilism would engulf society if such paltry views were to take hold. All the types of gruesome abuse we might think of would be acceptable because humans would be free to do anything.

As I have put here, it is preposterous. For sure, the readers of this post have countless times followed social conventions when playing board games, sporting matches and everyday interactions, without assuming that absolute truths reside behind the rules they followed. Similarly, moral rules must be followed for society to work. Because there is no enforcer outside society, moral rules need to be self-enforcing to be sustainable: moral systems must come with a range of formal and informal sanctions that ensure that nobody has an interest in stepping outside the rules of appropriate behaviour. Our moral intuitions are then a reflection of the fact that our cognition is well designed for us to navigate these situations, anticipate what is appropriate, be wary of what might not be, and so on.

Finally, the idea that moral systems are social contracts in no way implies that anything goes. On the contrary, it is reasonable to assume that among all the social rules we could imagine, only a tiny subset can be part of a sustainable social contract.

I expect that some readers will point out a gaping hole in my argument. Even if not all rules are permitted, there is no guarantee that some very unpleasant social contract cannot work as an equilibrium in a society. What are we to say about it then? Should we say that slavery or the subjugation of women is fine if another society seems to be stable with such institutions? This question is an important one, and it will be the topic of my next post.

References

Acton, J. (1887) ‘Letter to Archbishop Mandell Creighton (5 April 1887)’, in Acton–Creighton Correspondence.

Binmore, K. (1994) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 1: Playing Fair. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Binmore, K. (1998) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 2: Just Playing. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Binmore, K. (2005) Natural Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fukuyama, F. (2011) The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Hare, J. (2019) ‘Religion and Morality’, in Zalta, E.N. (ed.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 edn). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Lie-Panis, J. and André, J.-B. (2022) ‘Cooperation as a signal of time preferences’, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 289(1973), 20212266.

A recent Substack post questioned whether this usual interpretation of that poll overestimates the proportion of philosophers who are moral realists in the strong sense of believing that there are absolute moral truths that do not depend on what people think.

When people say “conventional morality is meaningless”, they often mean “it can be ignored”. In what follows I address that practical worry about authority and compliance, rather than a technical semantic claim about what moral words refer to. I have previously explained that a moral claim can be understood as true or false within a moral code. It is therefore meaningful, but in a reduced sense, compared with the absolute truth or falsity posited by moral realists.

The theory is not void of prescription. On the contrary, it will point out that mismatches between our intuitions, which have largely been shaped in small societies, and modern large societies create issues and that we can resolve them by having a clearer understanding of how social contracts work.

Not only many countries, including the US, include the death penalty as a possible legal sanction. But criminals, such as gunmen, are frequently killed by police in the course of their neutralisation, and this outcome is often seen as legitimate by the population.

Some people have pointed out that I use “should” when discussing knowledge and what we should do to acquire it. Let me say that this “should” is not smuggling in an absolute moral duty. It is not an unconditional “should”, rather, it is a conditional one: if we want to reach a better understanding, we should…

Some readers might argue that there is more to moral emotions. The desire to have a clean conscience, to have been true to oneself can drive behaviour. A quick answer (a long answer will warrant a post of its own) is that these perceptions can be explained with models of self-signalling.

That being said, such moral feelings would likely fade with time as Gyges learns that impunity is really safe. These moral feelings are meant to track the expected costs of violating the social contract. Experiencing repeated cost-free violations would eventually lead to learning (even if subconsciously) that these costs are lower than we previously expected. This is the very essence of Lord Acton’s observation that:

Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. — Lord Acton (1887)

The word “duty” is also not mysterious. It just means that we are required by the social contract to respect the rules of the specific contracts we sign with people in society.

People experiencing moral feelings more than others can be better cooperators because they are less likely to violate rules for short term gains. Lie-Panis and André suggest that it all comes from time preferences: people who are more patient see more long-term benefits from cooperation and are therefore more trustworthy.

Similarly, one does not give in to the temptation of a chocolate ice cream thinking “My level of sugar is low and I need to increase my inner reserves”. Instead, one just feels a craving for it.

The abandonment of their previously publicly stated principles by many current Republican politicians in order to keep their positions in the US is a sad illustration that this point has some bite.

To be precise, except for the particular situation where on average exactly 50% of people are likely to drive on the right or on the left, the random approach to driving would not be an equilibrium. For instance, if on average 55% of people drive on the right, everybody would have an interest in driving on the right, as they would then only face 45% of drivers driving on their side of the road in the opposite direction. Hence, it is not a stable pattern of behaviour. In a society where 55% of people drive on the right, we would expect it to progress towards a situation where 100% of people drive on the right.

A popular story about Britain’s left-hand traffic links it to medieval sword etiquette: right-handed riders allegedly preferred to pass on the left so that their sword arm faced any oncoming stranger, which then hardened into a general custom and was later codified in legislation (for example on London Bridge in 1756 and nationally in the Highway Act 1835).

In France, the option to drive on the right seems to have come from a top-down decision instead. A widely cited account has pre-Revolutionary aristocrats travelling on the left and forcing commoners to the right, with the Revolution encouraging everyone to adopt the “common” right-hand side in symbolic opposition to aristocratic practice. An official keep-right rule was introduced in Paris in the 1790s and later generalised, and French right-hand traffic subsequently spread to much of continental Europe, even though the precise mix of symbolic and practical motives is hard to pin down in the surviving sources.

In the United States, the convention to drive on the right also seems to have emerged from common practices. Right-hand travel emerged in the late eighteenth century from freight-wagon practice: teamsters typically sat on the left rear horse and held the whip in their right hand, which made it safer to have oncoming traffic on the left. Early state laws, beginning with a 1792 keep-right rule on the Philadelphia–Lancaster Turnpike and followed by New York’s 1804 statute, gradually entrenched right-hand driving across the country.

For a history of driving conventions, see Kincaid (1986).

For philosopher readers: This answer does not resolve all the criticisms leveraged against the conventional view of morality. What if a society accepted infanticide as part of its social contract (as some did in the past)? Would it be fine? I will address this question, which requires discussing the comparison of moral systems across societies, in my next post.

This notion of moral norms is strikingly similar to what Bicchieri calls social norms. How are then social norms different from moral norms? The paradigm example in the social norms literature is of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). For societies which practice FGM, it does not seem to be a moral norm. Though there can be an element of moral sentiments in cases where such norms are strongly internalised.

You fail to answer the Ring of Gyges objection successfully.

Per Binmore, only self-enforcing social contracts count as social contracts. Gyges is immune to social punishment of any kind (that's the entire point of the ring) and displays no internal guilt or regret in the scenario either, therefore we cannot say that any social contract has proved externally OR self-enforcing on him. Indeed, the point of the argument made is that social contracts are NOT 'self'-enforcing at all, that people obey them only out of fear of external enforcement.

Likewise, your version of 'ought' fails for the same reason. People routinely violate what the rest of society regards as moral constraints and often prosper nonetheless in any cost benefit calculation. Your formulation still leaves you effectively endorsing gangs, organized crime, drug lords, and human trafficking as viable societies and moral equilibriums.

I point that out not simply because they are abhorrent, you're quite correct that unpalatable outcomes are not necessarily incorrect conclusions, but because they rather present you with a fork you've been ignoring: at what point do you draw the line between dissidents within a society who may be legitimately punished by that society for 'moral' violations versus what amounts to two 'morally' distinct societies with conflicting 'moral' imperatives? When the law-abiding society says "you must cooperate with police" and the gang society says "snitches get stitches", your argument doesn't answer what the person in the prisoner's dilemma genuinely 'ought' to do except as a function of conditional risk/reward (Which, assuming the gang is willing to kill defectors, would presumably lead you to the counterintuitive position that it is morally wrong for a gang member to testify against his fellow gang members).

Appeal to 'consensus' is a mirage. There isn't one. People move in and out of multiple societies and sub-cultures with different and conflicting norms all the time. The smallest unit of 'society' reduces to the individual and if there is no external objective morality to which the individual must defer than the individual is effectively God and entitled to define his own morality and impose it on others as far as his own will and personal power make practical. 'Practical' may be a limited subset, but you still end up with uber-mench under your theory, the conclusion that social conventions are only truly binding on those who willingly accept them, and therefore anyone who simply rejects them is not subject to moral censure under them.

To return to a previous comment you made, if 'morality' is restricted to within each society because it relies on that society's particular consensus at that particular time, such that we cannot meaningfully condemn a Holocaust occurring within another society as 'wrong' or 'evil' in any sense beyond 'we wouldn't allow that here and now', anymore than whether or not to condemn a player as 'wrong' for holding the ball in his hands varies between football and soccer, you don't have a coherent morality. It really IS 'anything goes' so long as anyone else can be persuaded, tricked, or even forced to agree to it. You push back by noting that such 'arbitrary' arrangements aren't stable equilibriums (not necessarily true), but under your Appeal to Consensus they don't technically NEED to be long-term sustainable, you're sort of smuggling 'It's 'Good' to continue playing the game' in as a value even while denying theory of the good. Without that hidden assumption, even a cult that has everyone take out massive loans, do drugs and orgies and whatever else until the money runs out, then commit mass suicide to avoid any downsides to their hedonistic ways, would constitute a valid society with its own internal moral code and reasonable risk/reward calculus where such behavior is 'morally right' within your framework. You can't coherently draw your lines in terms of relevant population, place, or time, so it really does reduce to 'All things are permissible, but not all things are beneficial' at the individual level and 'it's only really wrong if you get caught or feel guilty' at the society level.

Your constructivism seems an insubstantial illusion, a mere rebranding of 'strategy' as 'morality', that breaks down whether applied to prominent philosophical hypotheticals or the real world as it is. I'm still not seeing anything that successfully differentiates this supposed 'morality' from 'How to Grow Your Small Business' or 'The Unofficial Player Guide to World of Warcraft'. 'Real Life is the Ultimate Game' runs into the problem that if there are no ultimate rules for life than you're left with a meta game regarding by whom and how those rules are invented, that meta game has no rules, and all imposed rules are essentially dependent on punitive force and/or bribes. It's ultimately 'Might makes Right', even if that 'might' is often communal rather than individual.