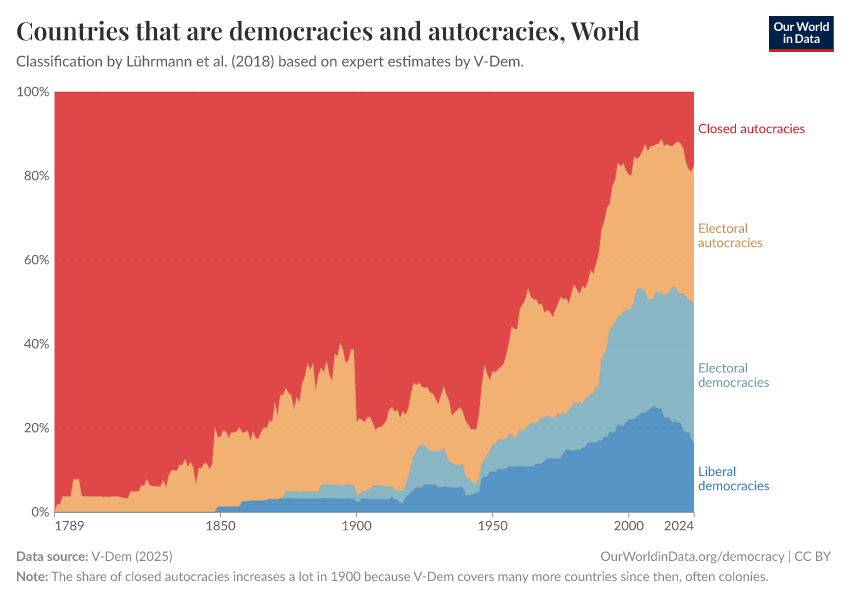

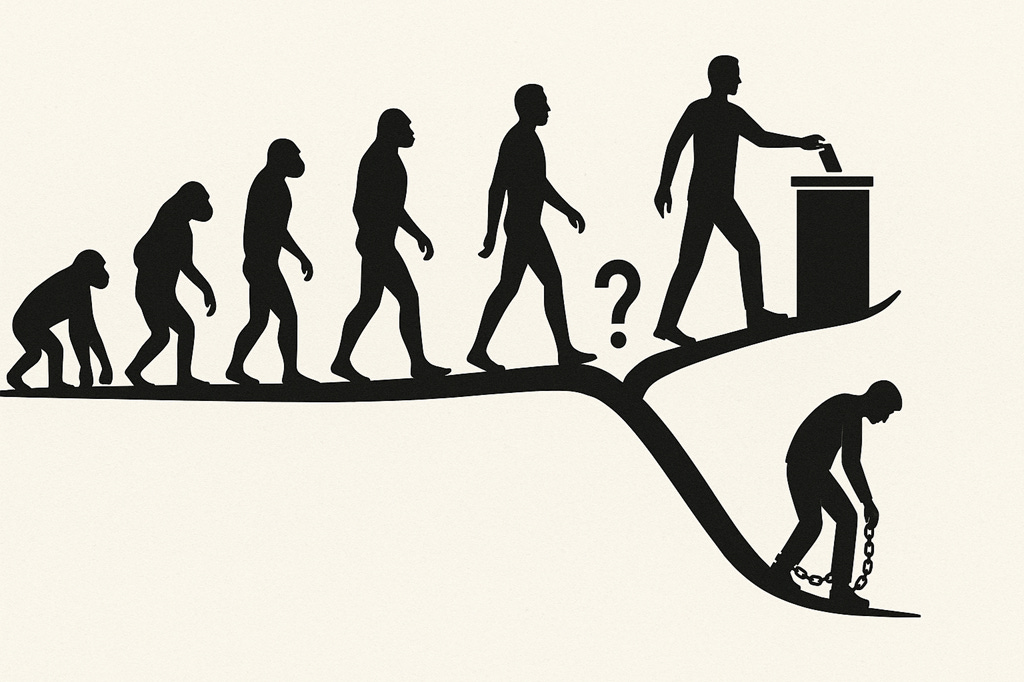

Does the arc of history bend towards democracy?

Why the world became more democratic, and whether it will continue

I conclude the series of posts on coalitional game theory and psychology on a slightly longer post on a big question: democracy and its future. The next series of posts will be on another big topic: what fairness is and where our moral sense comes from.

In his 1989 article “The End of History”, Francis Fukuyama noted the striking success of liberal democracy as a model of government:

What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War […] but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government. […] There are powerful reasons for believing that it is the ideal that will govern the material world in the long run. — Fukuyama 1989

Fukuyama’s article was published several months before the fall of the Berlin Wall. It appeared prescient in the wake of this momentous event. Its thesis, extended in a full book in 1992, became iconic of an optimistic liberal West seeing the progressive democratisation of the world as a natural consequence of economic development and rising education levels. Russia was holding elections and China was increasingly transitioning to a market economy. Democracy would somewhat naturally ensue.

Thirty years later, it is fair to say that this view was naive. Russia has fallen back into autocracy and China’s ruling elite has not only kept its political control over its population, it has tightened it in recent years. Far from spreading, liberal democracies have slightly retreated. Autocracies prop up dictatorial regimes in different parts of the globe.1 They even corrupt democracies’ institutions, channelling money to anti-system parties and sympathetic officials, and trying to influence public debates with astroturfed social media campaigns.

The institutions of liberal democracy, once seen as rock-solid, are now appearing more fragile than expected. New democracies like Hungary and Poland have seen serious steps back toward illiberal institutions. The US democratic institutions are being tested by its current President. And, in the coming years, European countries seem poised to experience a wave of far-right rulers with often unclear commitment to the letter and the spirit of democratic rule.

What should we expect in the future? Will the present time be a short hitch on the long road towards the democratisation of institutions in different parts of the world? Or, will the democratisation observed in the 19th-20th centuries instead be seen as a parenthesis in history? Could democratic institutions recede, even in the West?

To answer these questions, let’s first look into the reasons the world democratised in the first place. The answers to that question will help us assess whether we should expect democracy to continue to progress or not in the world.

Why has democracy progressed in the world in the last 200 years

There is a lot written about the history of democracy and its recent history. Many explanations have been proposed about why the West became democratic first, and why it happened when it did. In a sense, the profusion of explanations reflects uncertainty about the deep underlying mechanisms that explain why a wave of democratisation hit the West in the 18th century and not other parts of the world, like China.

The somewhat liberal-optimistic views of democratisation

Among the many explanations of democratisation, the most frequently held views in the West are somewhat compatible with a somewhat optimistic perspective making democratisation a natural process as countries get richer, more educated and better informed.

Prosperity and modernisation. Sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset (1959) has argued that democratisation came as a result of economic development, rising education, urbanisation, and the rise of a literate middle class, which is often seen as a prerequisite for democracy to flourish. As put by sociologist Barrington Moore Jr. (1966):

No bourgeoisie, no democracy.

Cultural change and values. An alternative account, more idealistic, suggests that it is the rise of different views and values, in particular with the Enlightenment, that led the masses to ask for more equality and rulers acting “for the people”.2

A related but different idealist account is offered by Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel (2005). Building on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, they argue that economic development allows people to look beyond immediate survival, producing a shift from survival to self-expression and emancipative values. These values increase mass demand for political participation, equality before the law, and accountable government.

These explanations are often given to the process of democratisation. However, they do not form a unified theory of how development leads to democratisation.3 Why would these different features of modernisation bring democracy? The present counter-examples of Russia and China seem to suggest that there is no clear automatic link between economic development and democratisation. And in regards to democratic ideas, were they really new? There have been democratic attempts in the past. And how do ideas lead to actual social change?

A non-idealist perspective

The perspective I adopt in this Substack is not idealist but naturalistic. With regard to political institutions, it is sceptical of explanations that assume people simply see the light of wisdom and decide to act “better”. Instead, it aims to explain institutions and their evolution as the result of individuals’ strategies to further their own goals, which are in part aligned (leading to cooperation) and in part not (leading to competition). In the political domain, these motives lead to coalitional strategies: people form groups (cooperation) to gain advantage over other groups (competition).

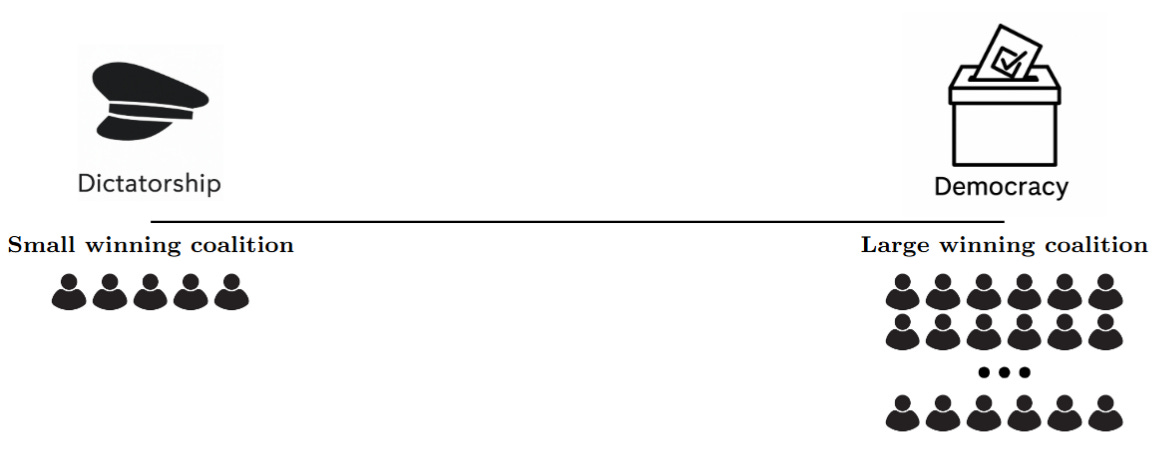

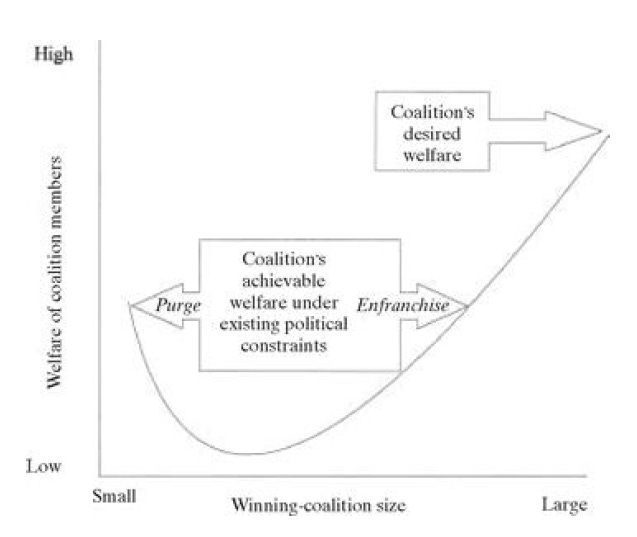

I have discussed in this series of posts how coalitional dynamics undergird fights for power and political debates. I have in particular described how democracy can be well understood with a coalitional perspective as a system where the winning coalition is large and can change easily.

From that perspective, the key question to ask is: what are the factors that might have led to changes in political regimes from authoritarian states based on small coalitions to democratic states based on large coalitions?4 This approach looks for fundamental changes in social structures that tilt bargaining power away from rulers, limiting their ability to rule with a small coalition.

The explanations we are looking for should characterise recent evolution and be valid across the significantly different cultural settings where democracy has thrived. A natural thing to look for is factors that make larger coalitions better able to gain bargaining power. What are the key ingredients affecting the ability of a large group of people to form a coalition able to gain political power?

Development and education might credibly have an effect on the willingness and ability of popular masses to organise and gain bargaining power. The exact mechanisms linking these factors to democratisation are, however, I feel, too often taken for granted because of a teleological bias: there is a natural direction of history, and it leads to the kind of institutions already found in modern, rich democratic countries.

Free from such an intellectual slant, let’s search for factors that change the balance of power between social coalitions, leading large-coalition regimes (democracy) to prevail. Among the different factors listed by Lipset, one stands out as increasing the masses’ bargaining power: cities!

The challenges of popular uprisings in rural societies

Cities, or rather the growing urbanisation of populations in modern times, likely create a strong factor in favour of democracy. The reason? It increases the ability of large masses of people to organise, gather, protest and seize the centre of power.

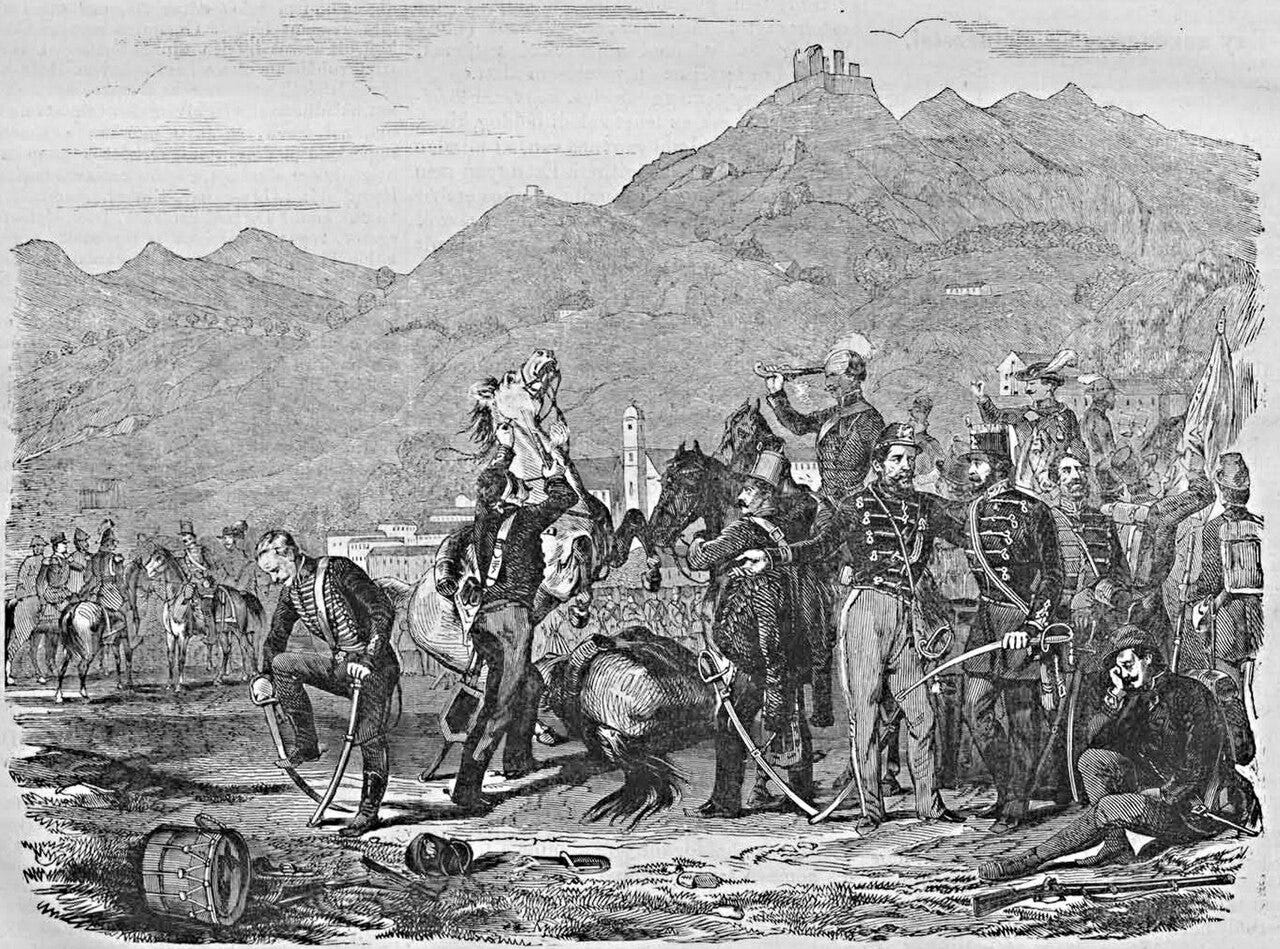

Popular uprisings have existed at all times, but their nature depends on the level of urbanisation. In mostly rural societies, towns are filled with elites who do not have much incentive to initiate large popular uprisings to extend political rights to most of the population.5 Political coups were common, but they typically replaced a leader and their faction with another leader backed by another faction.

The bulk of the population, composed of poor commoners, lived outside of towns and castles. In case of popular revolt, they faced almost insurmountable challenges to prevail. Consider the Jacquerie, a large peasant revolt in France in 1358 where thousands of peasants rose against the nobility in the northern parts of the country, destroying a hundred houses of nobles, and fielding an army of around 5,000 in a given battle.

To overcome the nobles, the rebels had first to coordinate. The revolt started from a specific location and spread spatially as others heard about it. It could therefore not be too quick, and peasants far away from the start of the revolt had likely very imperfect information on the magnitude of the revolt, its actions, and achievements. To be successful, they would have to gather in a unified crowd, which would take time, given their initial dispersal. All that would give time to nobles and their horse-riding knights to react and organise to defend the regime.

Furthermore, the peasants lived outside the centres of power and seizing them would prove extremely difficult. One of their attempts, at the fortress of Meaux, ended in a crushing defeat.

How cities facilitate popular uprisings

Consider now what modern revolutionaries have to do. With the growth of urbanisation, popular masses live in or near large cities. Cities facilitate three important aspects for a popular revolt to be successful:

Information: for a popular revolt to be successful, people not only need to be unhappy with the regime, they also need to know others are. There is no point going on the public square to berate the ruler alone, lest you just want to end up in jail. People’s knowledge about others’ attitudes towards the regime is therefore key. Cities make the spread of information among a large number of people easier and faster at all times, even when there is no revolt.

Coordination: even when people know that a large proportion of the population is unhappy with the regime, the emergence of a public revolt requires collective coordination: where to go, when and to do what. When a population is dispersed, a small revolt in one area can be put down before it spreads everywhere. Cities allow masses to quickly coordinate on mass protest.

Centrality: protesting is good, but, to gain power, a popular uprising needs to incapacitate the ruling coalition, either by taking its means of violence (e.g. taking over military barracks and weapons) or by disabling its ability to coordinate (e.g. taking over the buildings of power and communication). The ideal move in that perspective is to seize the ruler, who can no longer coordinate a counter-insurgency. Cities make such moves easier because the masses are close to the centres of power. While the Jacquerie had to attack fortresses to gain access to the rulers, urban protests are already within the ramparts.6

The academic research on the role of urbanisation

The idea that cities have helped improve the ability of popular uprisings to lead to regime change has been developed by political scientist Marc Beissinger in his 2022 book The Revolutionary City.7

Economists Edward Glaeser and Bryce Millett Steinberg also provided empirical support for the effect of urbanisation on democratisation (they labelled it the “Boston hypothesis” given the seminal role of that city in the American Revolution). They found that cities facilitate coordinated public action and enhance the effectiveness of uprisings.8

At a purely statistical level, countries that were more urbanized in 1960 experienced more democracy after that year, holding the initial level of democracy constant. This effect is particularly strong among countries that initially had low levels of democracy. — Glaeser and Steinberg (2016)

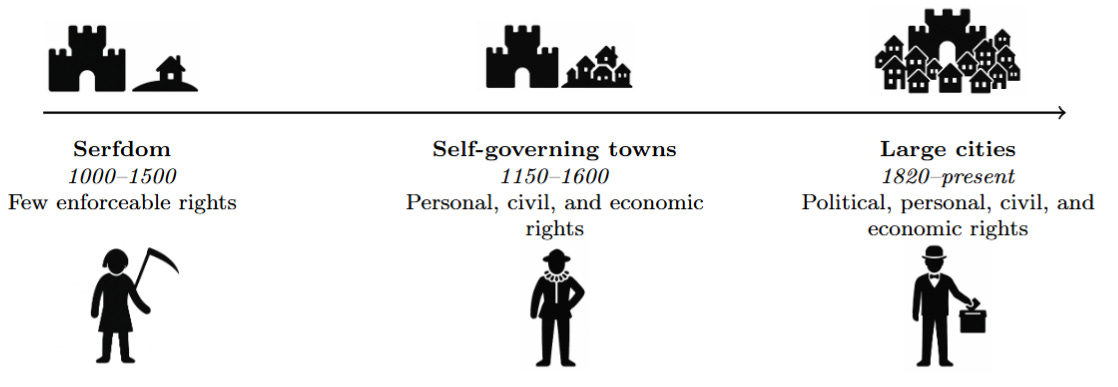

Urbanisation and individual rights

Even before democratisation, citizens had acquired more individual rights in many European towns than under serfdom. Rulers signed written agreements that let towns run their own courts, choose local councils, set rules for markets and crafts, and pay taxes on agreed terms. Living in a town could also bring personal freedom after a period of residence, summed up in the saying that “city air makes you free.” Towns sometimes sent representatives to regional assemblies, which gave them a voice on taxes and laws. 9

These gains came from city dwellers’ greater bargaining power. Towns were dense and could gather crowds quickly.10 Faced with that leverage, rulers often traded stable rules and legal protections in return for civil order (and often credit). The pattern shows up from the self-governing towns of northern Italy in the twelfth century to the powerful cities of Flanders and the Low Countries, and later across Central and Eastern Europe.11

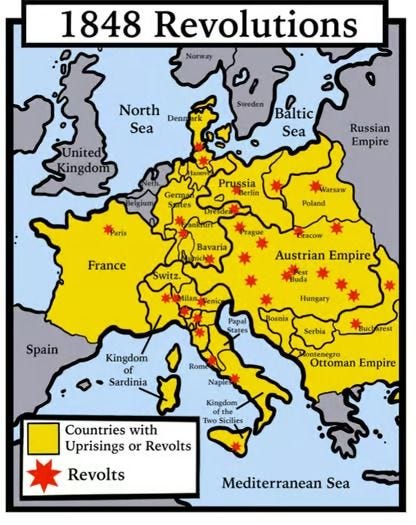

In the early 19th century, urbanisation picked up in Europe. With centres of power located in major urban centres, urban revolts played a major role in threatening rulers, culminating in the years of revolution in 1848.

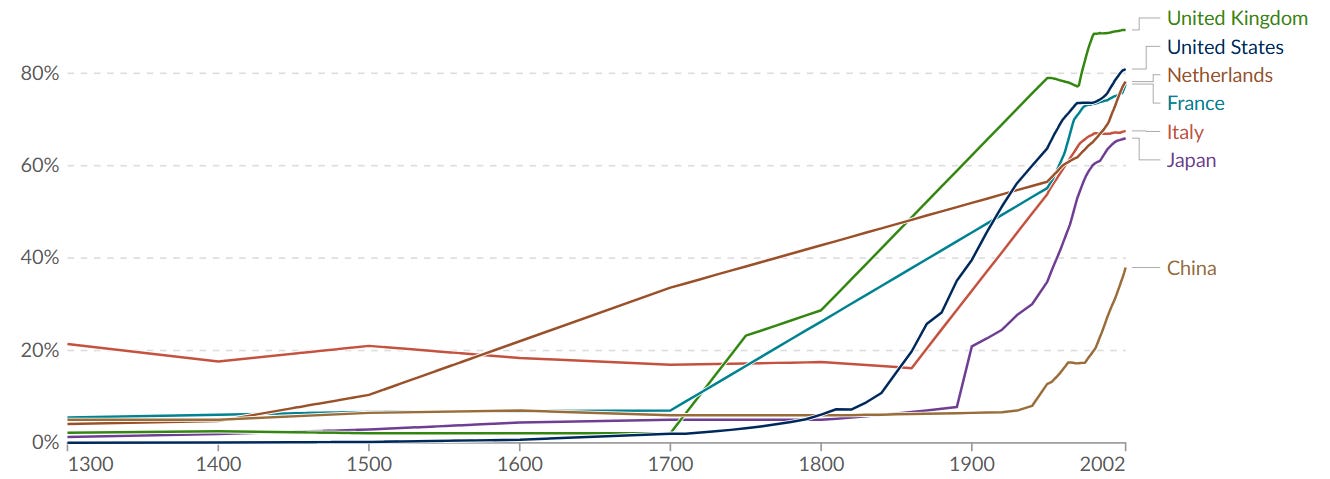

That coalitional perspective helps explain why the West democratised as it urbanised.12 It also helps explain why it did so before countries like China or Japan, which had tremendous state capacity.

We can now circle back to the other explanations of democratisation.

Modernisation is a prerequisite to urbanisation. Urbanisation is, in the end, a function of the ability of a country to sustain a larger share of the population that does not produce food. Europe urbanised earlier thanks to several factors that helped feed and sustain larger populations in cities. First, economic modernisation increased the productivity of farmers.13 Second, European cities grew as trade centres able to import more food from abroad, in exchange for manufactured goods. Third, the spread of the potato as a staple food had a substantial effect, possibly accounting for one-quarter of urbanisation in Europe,14

Egalitarian ideas emerged as a reflection of the greater bargaining power of large masses of city dwellers.15 A famous criticism of liberal ideas about democracy is that it was just an ideology to rationalise the interests of the bourgeoisie.16 Engels, Marx’s co-author, explicitly stated this:

[…] the French philosophers of the 18th century, the forerunners of the Revolution, appealed to reason as the sole judge of all that is. […] this eternal reason was in reality nothing but the idealised understanding of the 18th century citizen, just then evolving into the bourgeois. The French Revolution had realised this rational society and government. — Engels (1892)

Why democracy kept expanding

While Engels was right in seeing the emergence of liberal democratic ideas as reflecting the interests of the bourgeoisie, he was wrong in thinking they were only that. Liberal and democratic ideologies are propositions of alternative social contracts. They have to be—like other contracts—consistent and binding.17

Liberal democratic ideas were typically framed in universal ideas “of, by, and for the people” that were intellectually more appealing than a narrow claim for rights restricted to the bourgeoisie. However, once the idea of equality and government for and by the people prevailed, it took a life of its own, often being hard to stop at arbitrary lines in favour of a narrow group of wealthy bourgeois.

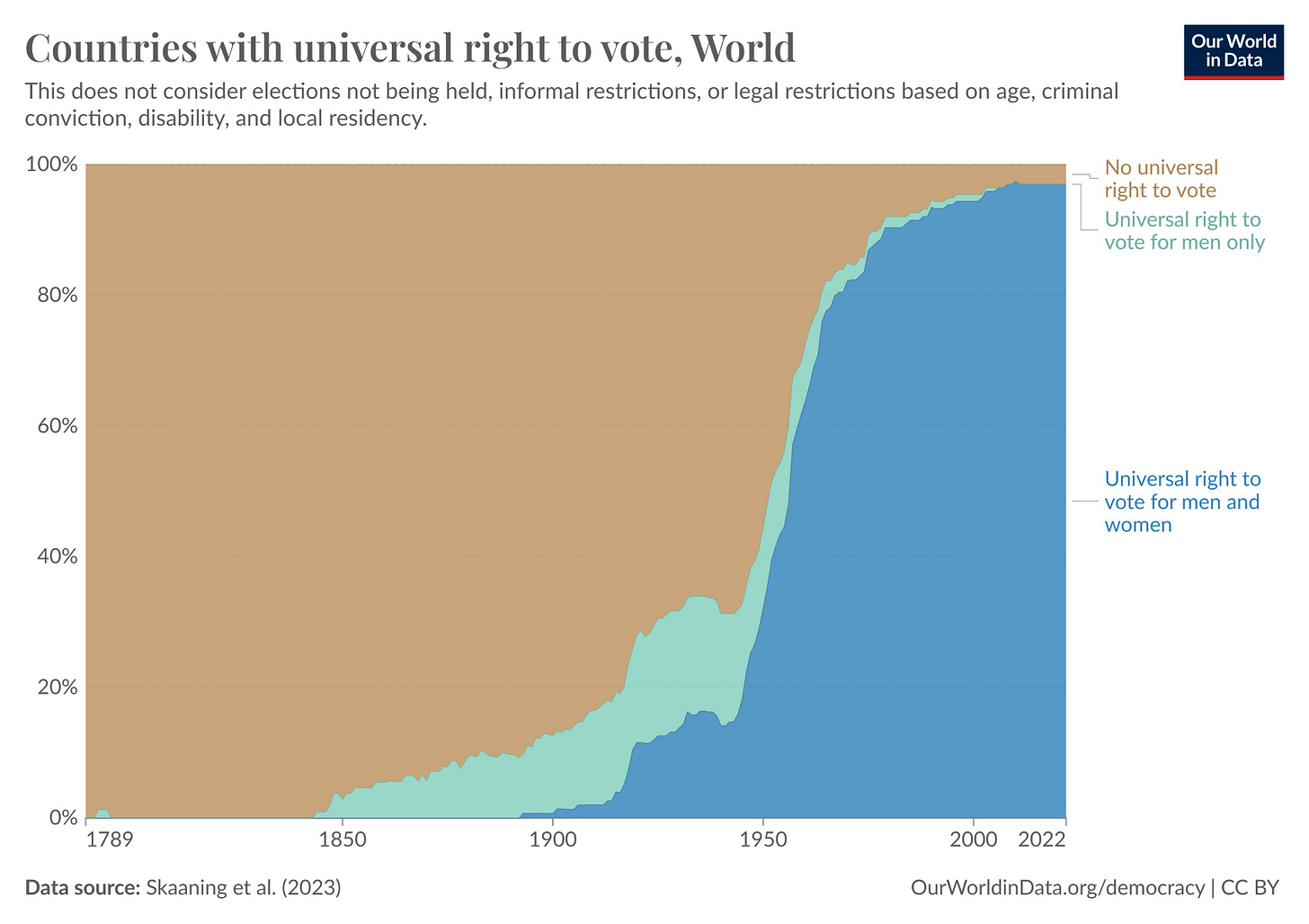

Hence, while the initial stages of democratisation in Western countries typically gave voting rights to only a minority of the population (men with some level of wealth), the extension of the franchise was reasonably fast as the masses asked to be included in the franchise. At the start of the 20th century, most male citizens had the right to vote in the UK (67%), US (100%18) and France (100%). In much of the democratic world, women’s national suffrage followed universal male suffrage within a few decades.19 20

Will democratisation continue?

A non-idealistic take on democratisation

This coalitional perspective on factors that helped drive democratisation in the last 200 years is also relevant to think about whether this process will continue in the near future. It demystifies the process of democratisation by not relying on some teleological principle, a historical arc bending towards democracy. Instead, it points out that historical conditions became, in recent times, more favourable to large coalition regimes.21 Whether democracy continues to spread will depend on such conditions persisting and spreading to currently non autocratic countries.

Good news for democrats is that there are good reasons to think that democracies are fairly stable. In their book The Dictator’s Handbook, Bueno de Mesquita and Smith point to the fact that the most democratic countries seem resilient to authoritarian backsliding. The reason is that members of large coalitions often lose when the winning coalition shrinks and they, therefore resist such changes.

Once nations have successfully transitioned to large-coalition democracies, these institutions become locked in. — Bueno de Mesquita and Smith (2022)

Past regressions and backlash

Nonetheless, it does not mean that historical progress towards democracy is straightforward. Human history has certainly not been marked by one-directional progress towards democracy and political equality. The prehistorical evidence suggests that our ancestors often lived in communities with much more political equality than the large scale states and empires that emerged after 4,000 BC. The transition to agricultural societies and the ability to accumulate stored resources facilitated the concentration of power in a small elite in large societies.22

Later in history, regimes with democratic aspects have often appeared and disappeared. Athens is the most famous one. To it one can add the Italian republics like Venice and Genoa, the free cities of the Holy Roman Empire, the Dutch Republic and many others. A common feature of these past polities with some aspect of democratic governance was their small size, centred around a city. In The Spirit of the Laws, Montesquieu argues that republics work best in a small city because the will of the people is easier to understand in a small place.

In a large republic the public good is sacrificed to a thousand views; it is subordinate to exceptions; and depends on accidents. In a small one, the interest of the public is easier perceived, better understood, and more within the reach of every citizen; abuses have a lesser extent, and of course are less protected. — Montesquieu

But the coalitional perspective I presented suggests a simpler reason: urban centres naturally give people more bargaining power. Large states counterbalance this, because soldiers from other parts of the state can be used to crush an urban revolt. Autocracies have always known that local soldiers’ loyalty can fail when asked to repress their local fellow citizens, who include their acquaintances and relatives. For instance, in Vienna 1848 the Habsburgs relied on non-Viennese forces (notably Croatian troops) to retake the capital.

Small republics have often been conquered by larger states where the balance of power was not as favourable to the masses of people. Similar reasons underlie, I believe, the disappearance of self-governing cities in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries as national states centralised power.

History has therefore often seen movements back and forth towards more democratic institutions.

Finally, another challenge to the idea that history naturally progresses towards democracy is that autocracies can learn and adapt to changing environment increasing the risks of popular uprisings. In the 19th century, they learned from the danger of having a high concentration of poor working-class people in the centre of cities.

The acclaimed architectural style of Paris with medium-high storey buildings and wide avenues is, to some extent, downstream of political considerations. Baron Haussmann was tasked by Napoleon III to revamp Paris in a way that had two important practical implications: first, large avenues replaced narrow streets, making military movements across the capital easier and the blockade of streets with barricades harder; second, the destruction of slums and their replacement with modern buildings led to a substantial movement of poor dwellers outside the city (and its fortifications).23

In their fight against democracy, autocrats not only learn, they can unite to avoid the rule by the people that would end theirs. From 1809 to 1848, Metternich, the Austrian Minister of Foreign Affairs was a key mastermind in organising a coordination of autocracies, including the signature of treaties between monarchies allowing them to intervene to help each other if threatened by a revolution. against democratic movements in Europe. In 1836, he stated “In Europe, democracy is a falsehood” to explain that democracy was impractical and infeasible on the old continent, unlike in the US. This cooperation led to a series of military interventions by European autocracies to crush nascent liberal and democratic movements in Italy (1821, 1831, 1838), Spain (1823), Poland (1846) and Hungary (1849).

In the 21st century, again autocrats from diverse and ideologically unrelated regimes are united in their opposition to losing power to democratic institutions. They argue, like Xi, that democracy is unworkable for their country.24 They intervene in other countries to prevent autocracies from being toppled by popular uprisings like Russia in Belarus and Syria. And they explicitly work to unravel a world order still dominated by liberal democracies.

Future challenges: AI as empowering rulers or citizens?

This coalitional perspective also helps us think about one of the possible future challenges to democracy and its progress: AI and the opportunities it might offer autocracies to control citizens.

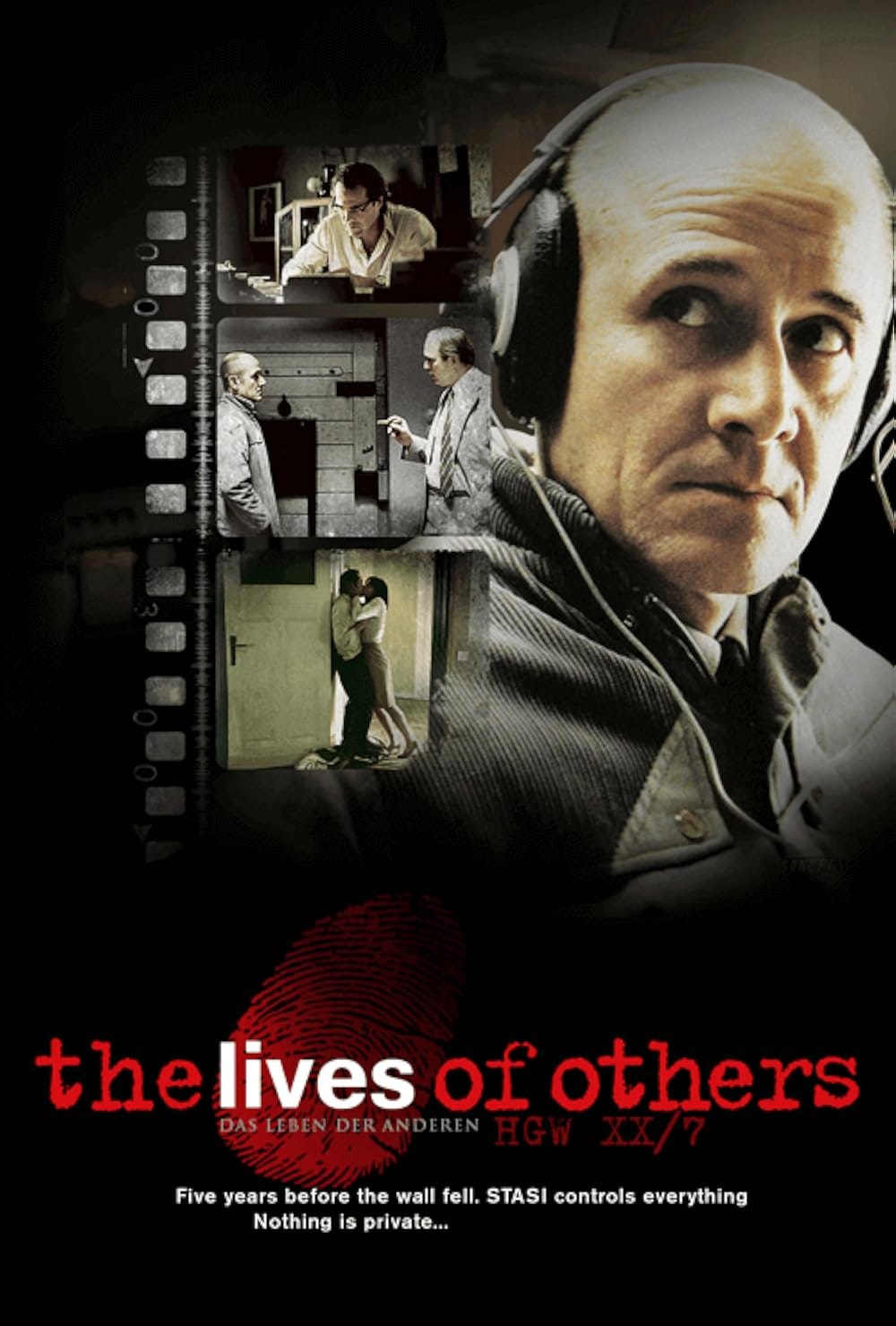

The best way to prevent dissent is to prevent people from expressing their true views and coordinating their beliefs and actions via exchanges of ideas and information. Authoritarian regimes have achieved this by creating societies where people could not be sure that their friends, colleagues or even family members would not denounce them for instances of wrongspeak.

One of the states that went the furthest in the monitoring of citizens’ private dealings and discussions was East Germany. The excellent movie The Life of Others represents how the political police, the Stasi, was monitoring people’s lives, often bugging their homes. The problem is that such a system is extremely costly in manpower. According to the Encyclopedia Britanica, in 1989 the Stasi had 100,000 regular employees and up to 2,000,000 informants.

In the control of citizens’ activities, autocracies face the challenge of having enough human resources to perfectly monitor citizens who might constantly devise new ways to communicate and often be critical while avoiding being found out.

In that perspective, AI offers potentially game-changing tools by making it possible to monitor everybody’s communication and process an enormous amount of information to detect dissent. Powerful AI tools allowing such a thing would deter revolts and bolster authoritarian regimes.

By allowing governments to monitor, understand, and control their citizens far more closely than ever before, AI will offer authoritarian countries a plausible alternative to liberal democracy. — Wright (2018)

In George Orwell’s novel 1984, the total control of society is ensured by telescreens: two way screens that broadcast pictures and monitor what you are doing. Such tight monitoring might become within reach for totalitarian states via the use of AI. With enough computing power, it might become possible to automatically screen communication and activities to detect any sign of dissent on a large scale, without an army of monitors.

While such a use of AI seems to be a risk, we can also envisage ways in which AI might improve democratic institutions. For instance, by providing personal fact-checkers to every citizen, AI might limit the asymmetry of information between leaders and citizens which allows political leaders to get away with convenient half-truths and deceptive narratives. If so, it might increase the accountability of political leaders.

It is hard to predict how AI will impact political systems. However to the extent it does it is fair to expect that it will likely be by affecting the coalitional dynamics that undergird political competition and cooperation in modern states.

We are often tempted to think that there is a sense to history, that its cogs are, for some reason, geared to deliver social progress and greater justice. Martin Luther King famously stated this idea as the fact that the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice. Recently, US President Obama often repeated the same idea.

The naturalistic perspective I take in this Substack avoids any teleological perspective. There is no a priori reason for history to deliver better and fairer societies (according to the criteria we currently use). It is with such a historically agnostic angle that we need to look at the past to understand our future. The world likely did not become democratic simply because of technical progress, the progress of knowledge and other aspects of our modern societies. It became more democratic because recent evolutions of social structures made large coalition regimes (democracies) more likely to emerge and persist than small coalition regimes (autocracies).

In this post, I suggest that urbanisation is a reasonable candidate for driving such a social evolution, as it tilted the balance substantially in favour of the large masses of people living as city dwellers.

It is a priori not clear that there is a historical necessity for factors favouring large coalitions to become more and more prevalent in the future. Indeed, one can entertain mechanisms that would undermine the bargaining power of the popular masses and allow a narrower elite to concentrate more power.

The rise of AI and the likely (but hard to predict) disruptions it might create might be a factor that could reinforce the power of ruling elites and their ability to prevent popular dissent. At the same time AI could also empower citizens and give them a greater ability to keep rulers accountable. In the discussion on the possible risks associated with AI, the political risks and opportunities it represents for democracy should be an important topic of discussion.

On this topic, as on any other related to politics, those interested in defending and promoting democratic institutions should not engage in vague, idealistic discussions about general factors, such as wealth and education, that might lead to more democratic institutions. Instead, they need to understand whether existing social and political rules favour the emergence of small or large winning coalitions, and how to change these rules to make winning coalitions systematically large.25

Housekeeping: referrals

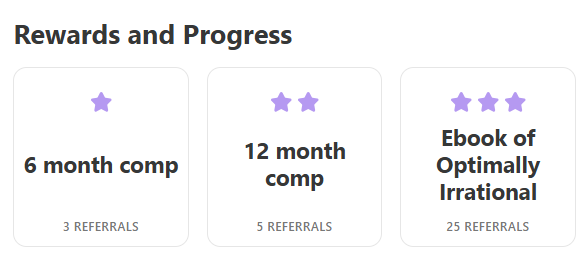

You, dear reader, are clearly among the best placed to identify others who would be interested in the essays I post here. I have now turned on the referral reward programme to tap into your knowledge of possible future readers of this Substack who just need to be told about it.

The rewards for multiple referrals are below. They include a free ebook of Optimally Irrational.

References

Acemoglu, D. & Robinson, J.A. (2006) Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Allen, R.C. (2009) The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bairoch, P. (1988) Cities and Economic Development: From the Dawn of History to the Present. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Moore, B. Jr. (1966) Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Boston: Beacon Press.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., Smith, A., Siverson, R.M. & Morrow, J.D. (2003) The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bueno de Mesquita, B. & Smith, A. (2022) The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior Is Almost Always Good Politics. New York: PublicAffairs.

Collier, P. (1913) Germany and the Germans from an American Point of View. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons.

Dorward, N., Fox, S. & Hoelscher, K. (2025) ‘Urbanisation, Democracy, and Political Regime Transformations’, Political Geography, 122, 103382.

Dunn, J. (2005) Democracy: A History. London: Atlantic Books.

Earle, T.K. (1997) How Chiefs Come to Power: The Political Economy in Prehistory. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Engels, F. (1892) Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Trans. E. Aveling. London: Swan Sonnenschein.

Hobsbawm, E.J. (1973) ‘Cities and Insurrections’, in Revolutionaries: Contemporary Essays, pp. 312–330. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Howard, P.N. & Hussain, M.M. (2013) Democracy’s Fourth Wave? Digital Media and the Arab Spring. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Inglehart, R. & Welzel, C. (2005) Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kowaleski, M. (ed.) (1996) Medieval Towns: A Reader. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press.

Lipset, S.M. (1959) ‘Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy’, American Political Science Review, 53(1), pp. 69–105.

Montesquieu (1748/1989) The Spirit of the Laws. Ed. and trans. A.M. Cohler, B.C. Miller & H.S. Stone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunn, N. & Qian, N. (2011) ‘The Potato’s Contribution to Population and Urbanization: Evidence from a Historical Experiment’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(2), pp. 593–650.

Reynolds, S. (1997) Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Robinson, J.A. (1999) ‘When Is a State Predatory?’ CESifo Working Paper No. 178. Munich: CESifo.

Scott, J.C. (2017) Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Stasavage, D. (2011) States of Credit: Size, Power, and the Development of European Polities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stasavage, D. (2020) The Decline and Rise of Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tilly, C. (2004) The Politics of Collective Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tilly, C. & Tarrow, S. (2015) Contentious Politics. 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press.

Treisman, D. (2020) ‘Economic Development and Democracy: Predispositions and Triggers’, Annual Review of Political Science, 23, pp. 241–257.

Wright, N. (2018) ‘How Artificial Intelligence Will Reshape the Global Order’, Foreign Affairs.

Russia has backed multiple dictatorial regimes in Africa, Venezuela in South America, Syria and Iran in the Middle East, Belarus in Europe. China is backing North Korea and Myanmar in Asia and Russia in it war against Ukraine.

Dunn (2005)

In a recent summary of the available explanation of possible links between economic development and democratisation, Daniel Treisman (2020) stressed that:

Scholars continue to disagree about the relationship between economic development and democracy.

His well-referenced literature review, points to a range of possible links, each of them uncertain (emphases mine):

Economic development may affect democracy through various mechanisms. Among demandside factors, development could work by mobilizing workers, expanding and strengthening the bargaining power of the middle class, spreading education, and—in later stages—transforming the nature of work. Increasing education can, in turn, hasten transition by enhancing citizens’ political skills and efficacy, fueling growth of independent media, swelling the cohort of protestprone college students, and reshaping values. Education, independent media, and values change may also impede backsliding. Treisman (2020)

This distinction is made by Bueno de Mesquita, B et al. (2003).

Towns were typically oligarchic and ruled by an elite with limited incentives to extend rights outside the city walls (Stasavage, 2011).

The fact that quick access to centres of power increases the risk of successful revolts is not lost on leaders. President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire is quoted as saying to President Juvénal Habyarimana of Rwanda in response to a request for armed support to help fight an insurgency:

I told you not to build any roads .. building roads never did any good. I’ve been in power in Zaire for thirty years, and I never built one road. Now they are driving down them to get you. — Jeune Afrique, 1991 (cited in Robinson, 1999)

For antecedents, see Hobsbawm (1973) on the insurrectionary city and Tilly (2004) on urban contention; Beissinger systematises how urbanisation scales disruptive capacity into regime change.

The idea that cities have increased the chance of successful uprisings was also mentioned by historians Eric Hobsbawm (1973) and Charles Tilly and Sidney Tarrow (2015). A recent study confirmed the role of cities, finding that the size of the urban population is linked with regime change and democratisation.

See Reynolds (1997) and Kowaleski (1997)

See Tilly and Tarrow (2015). They were also wealthy and could disrupt trade or refuse loans. Their capacity to do so depended on bargaining power—that is, on the costs rulers would incur to rein them in during a conflict.

Stasavage (2020)

For the reader interested in political science, here is a discussion of the causal link between popular uprisings and democracy and why popular uprising do not simply lead to other regimes, such as populist led autocracies like the communist regimes of the 20th century.

The reality of popular uprising is that they typically do not succeed without key actors from the winning coalition defecting, in particular those in charge of the armed forces. Successful revolutions are often popular uprisings articulated with splits in the ruling coalition. Indeed, the masses often do not control the bargaining over regime change following an uprising, and many if not most popular revolts end up switching an autocratic ruler for another one. Popular uprisings are therefore not a guarantee of democratisation.

In fact, one could even question the premise that if a popular crowd makes a regime fall, they would necessarily install a democratic government. They might instead want to choose another leader, in particular if that leader favours their specific coalition. It is therefore necessary to explain why democracy would be appealing to members of a popular revolt.

Why democracy can appeal to the massses. If the members of a popular uprising keep a system based on a small coalition, so that it favours them today, it might change in the future to a situation where they would not be part of the winning coalition anymore. A democratic system with a large and flexible coalition offers a kind of insurance to the masses. Free elections with a large electoral body mean that you have a large chance to be in the winning coalition, and extensive rights imply that when you are not the winning coalition, the rulers face severe constraints in what they can do to you. Democracy is appealing for that reason.

Why democracy can appeal to elites. Among those who could be the backers of an authoritarian regime, democratisation can also be an insurance against being dropped from the winning coalition and losing one’s privileges. For that reason, political scientists Bueno de Mesquita and Smith suggest that elites are more likely to support democratisation when the future composition of the winning coalition is most uncertain: at the start of the tenure of a new ruler or at the end of it (e.g. when he is very old).

Times and circumstances that heighten the risk of coalition turnover engender an appreciation of democracy among political insiders. — Bueno de Mesquita and Smith (2022)

Why democracy can appeal to rulers. As the masses’ bargaining power increased with urbanisation, democratisation can offer rulers insurance against revolution that would unsettle them. Economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson (2006) argue that when mass unrest is credible and repression is costly, elites extend the franchise as a credible commitment to diffuse revolution.

Allen (2009)

Nunn and Qian (2011)

I do not claim that urbanisation is the single and unique factor that drove democratisation in the West. However, I think it is a good candidate to be the main driving factor. Discussions on why the West democratised often come with a large laundry list of factors. A coalitional perspective helps cut through this list and ask: what is likely to have driven an increase in bargaining power from popular masses. Such variations in bargaining power are likely to be the prime drivers of democratisation.

Another possible contributing factor might have been, the divisions of Europe into a large number of polities, which also improved political entrepreneurs’ bargaining power by giving them exit options in case of political repression (e.g. Voltaire, Thomas Paine and Karl Marx).

Bourgeois comes from Old French, meaning inhabitant of a bourg (walled town).

They are not binding in the sense that people cannot violate them. They are binding in the sense that those who make social claims based on ideology tie themselves to respect other implications of this ideology, lest they appear hypocritical and their other ideological appeal lose any credibility.

These were the legal rights, but in the South de facto disenfranchisement excluded many Black voters until the mid-1960s.

There are a few exceptions to this pattern, notably France (97 years) , Switzerland (123 years), and Greece (around 80 years).

In their book The Logic of Political Survival (2003), Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson, and James D. Morrow also suggest another reason why the franchise tends to expand as countries become more democratic.

In systems with a large winning coalition, leaders maximise political survival by providing public goods valued by most of the population rather than buying support with private goods for a few. Because a large coalition dilutes the per-capita value of private payoffs, members prefer better public goods, and are often willing to accept further franchise expansion that enlarges the coalition, over the small private advantages available in narrow-coalition regimes.

In the same perspective, in more recent times, the spread of means of communication likely increased the ability of large social groups to share information and coordinate. Social media have been considered to be a major factor in the Arab Spring in 2011 (Howard and Hussain, 2013).

See Earle (1997) and Scott (2017).

There is a debate on the extent to which these intended military advantages drove the architectural design choices of Haussmann. Haussmann mentioned the disappearance of popular riots as a benefit from his work. He did not state such elements as outright goals though these are the kind of benefits in favour of rulers that are best kept behind motives of improvements of social welfare.

The idea that Chinese people are somehow not ready for Western democracy is frequently expressed by the Chinese ruling elite. Xi, for instance, said:

Democracy is not Coca-Cola, which could be produced with one formula and taste exactly alike across the world [..] Due to differences in history, culture, system and development level, peoples have naturally different understandings of democracy and various methods of achieving it.

The success of democratic Taiwan is an inconvenient counterexample to this narrative.

To do so, I could not recommend more Bueno de Mesquita and Smith’s excellent book The Dictator’s Handbook.

Lionel Page’s latest essay, “Does the arc of history bend towards democracy?”, is a brilliant piece of naturalistic political analysis.

He dismantles the teleological myth (inherited from Enlightenment optimism and Fukuyama’s “End of History”) that democracy is the inevitable destiny of human societies. Instead, he shows that democratic institutions emerged not from moral enlightenment but from coalitional dynamics - shifts in bargaining power that urbanization, communication & coordination made possible. As he rightly notes, ideas follow power. His essay resonates deeply with the argument I make in the book Os Demónios da Nossa Natureza: democracy is not our natural political state - it’s an institutional exception built on fragile evolutionary ground.A superb and lucid analysis that deserves wide readership.

God I hope not. Democracy is mob rule.