Why we so often fail to work together

The unescapable reality of intracoalitional entropy

A regular frustration when working in a firm, party, or association is that internal conflicts harm the group. Why can’t people just get along and collaborate towards the group’s goal?

Political scientist Mancur Olson pointed out that groups are composed of individuals whose interests are not fully aligned. Hence, there will always be a tension between a group’s goals and the individuals’ interests within that group.

Unless the number of individuals in a group is quite small, or unless there is coercion or some other special device to make individuals act in their common interest, rational, self-interested individuals will not act to achieve their common or group interests. - Olson (1965)1

A group of employees may want to secure a contract, but each member wants their individual contribution to be recognised. A football team wants to win a match, but each striker prefers to score rather than pass the ball. A political party wants to win an election, but each contender for top political positions focuses on strengthening their own bargaining position in case their party wins.

Such conflicts and their negative effects are pervasive and a major reason we so often fail to work efficiently together. I’ll call the negative effect of these conflicts of interest intracoalitional entropy. It is the messy nature of collective group action that emerges from the unaligned incentives of individuals.

Intracoalitional conflicts

Every coalition—associations of people who can achieve more together than alone—features intracoalitional conflicts.2 While people share an interest in their coalition’s success, they have diverging interests in how to share the spoils of this success. There is an intrinsic tension for any coalition member: fighting with a coalition to secure a coalition victory versus fighting within a coalition to increase one’s share of the prize.

Conflicts between people within groups are often referred to as “personality issues,” but this is typically a misdirection. These conflicts are usually not primarily the result of the specific personalities involved, but rather of disagreements over how to share the benefits and costs that come with the group’s existence. This fact is key to making sense of most issues arising within groups.

Disagreements on the allocation of effort

Collective action requires people to invest time, effort, and resources. The economic literature, following Olson’s insights, has extensively examined the challenges involved in getting people to contribute to a group effort. A key issue arises from the fact that individuals’ contributions are typically not fully observed. Therefore, it is often not possible to know whether people are trying their hardest in collective work or whether they are, to some extent, shirking. This is a classic instance of what economists call moral hazard (Holmstrom, 1982).

Fighting for prestige and social recognition

Groups create their own social currency: prestige and recognition by peers. For a group to function well, these social rewards should be allocated to those who contribute to the group’s goals—those who help the party win elections, the firm make a profit, or the church gain new followers (Maner, 2017).

The problem is that while effort and contributions are made by individuals, success typically befalls the group as a whole. It is often not straightforward to determine each person’s contribution to the group’s achievement. Consider a football match. When a team scores a goal, it is usually the result of many individual actions. While the scorer was decisive, many other players may have contributed to the action, and it can be difficult to determine and ascribe credit—or blame—across players.

People are therefore often jockeying for their share of the praise for collective success. This is a major issue in organisations that is often underappreciated by commentators. The apportionment of credit and blame determines career advancement in firms and prestige in social settings. Strategically “hogging the limelight” and claiming more than one’s fair share of work is therefore a strategy that can pay handsomely—and it is indeed pervasive.

These concerns do not start at the evaluation stage, when the collective work is done and individuals’ contributions have to be assessed. The outcome of this final phase often relies heavily on how things have unfolded, and therefore the concern for the limelight shapes, in anticipation, individuals’ behaviour throughout the collective work.

In short, people’s behaviour in collective endeavours is frequently distorted by the competitive aspect associated with the sharing of collective gains. Consider the often-criticised “meeting” in organisations: Alice speaks longer than needed to ensure her contribution will be remembered; Bob provides selective information that flatters his own role; Candice nods approvingly at the manager’s point in the hope of gaining her good graces—and so on.

Diverting effort towards personal rewards in teams

The saying “There is no I in team” is meant to indicate that people should subordinate their personal interests to team goals when working with others. If this needs to be proclaimed, it is because people often face opportunities to allocate their efforts in ways that maximise their personal rewards, rather than the chance of achieving the team goal.

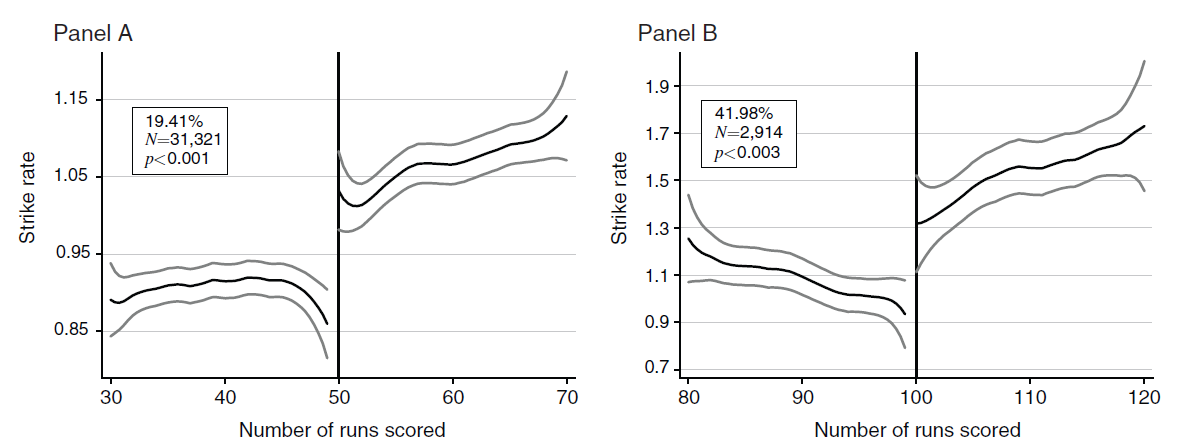

My favourite example of this comes from a study I worked on with Romain Gauriot. Identifying how people distort their behaviour for private benefits is difficult, but we identified a situation in the sport of cricket where this could be pinpointed. Cricket is a batting game where batters score points (“runs”) for their team. For batsmen, their actions can lead to both collective gains (team victory) and individual rewards (personal batting score).

For traditional reasons, individual batting scores are celebrated in multiples of 50. A batsman receives significant recognition for scoring 50, 100, 150, 200, and so on. There is therefore a big difference for a batsman between scoring 99 runs and scoring 100. That additional run transforms the player’s achievement into a “century”.

What we found: players dramatically change their behaviour around these milestones, slowing their scoring rate (“strike rate”) to reduce risk-taking (and the chances of being dismissed) in order to cruise past the milestone. Then, their risk-taking shoots back up. These variations are inefficient for the team, as players take too long to score before reaching milestones, which slows the team’s overall progress. But it increases the players’ chances of securing an individual reward—their milestone.

While it is rare to have such a clean proof of this phenomenon, it is most likely pervasive in organisations. In our case, we observed it in a setting where individual behaviour is highly visible. It is likely to be even more widespread in contexts where actions are less observable.3

Fighting for power

A specific type of social recognition in groups is the selection for positions of leadership. These positions are a major prize over which people compete.

Disingenuity

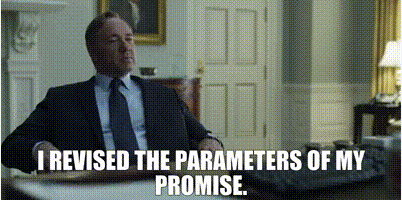

In the contests for power, contenders often have to make promises, take positions, and manage the conflicting expectations of their backers. In these situations, the best strategy to secure or retain power is not necessarily to be honest about one’s intentions and positions. This is one of the basic principles laid out by Machiavelli for leaders to succeed in practice:

A prudent ruler ought not to keep faith when by doing so it would be against his interest. - Macchiavelli (1532)4

It is, for instance, commonly understood that politicians’ promises are highly unreliable.

Sabotaging

Because power positions are in limited supply, the competition for power often takes the form of a zero-sum game: what one gains, another loses. In firms, this leads to what economist Edward Lazear called industrial politics (Lazear, 1995). It can result in sabotaging behaviour: those in the race for leadership spots can improve their position not only by performing well for the group, but also by negatively affecting the performance of other contenders.

A simple way to do this is by withholding useful information or opportunities—ensuring others are less effective within the organisation. More direct, though riskier, tactics involve undermining others through reputation manipulation (e.g. gossip) or making coalitional moves against them—for example, by not backing their promotion or that of their supporters.

Loyalty over performance

For incumbent leaders, a priority is to prevent potential contenders to threaten their position. A consequence is that those in leadership positions often have a strong preference for loyalty, which can trump the preference for having high-performing subordinates.

Hence, political leaders have incentives to appoint subordinates who are not too competent (Egorov and Sonin, 2011; Zakharov, 2016), managers of public agencies who are above all loyal (Wagner), and military leaders who are not too skilful (Talmadge, 2015). This phenomenon helps explain why armies in dictatorships are often heavily inefficient:

The same practices that generate battlefield effectiveness also improve the military’s ability to launch or support a coup, defined here as the seizure of the levers of state power by a small group of armed insiders. […] Promotion patterns are likely to be entirely a function of political loyalty, with deliberate selection against proven combat prowess. - Talmadge (2015)

Performance benefits the organisation as a whole, while loyalty benefits the incumbent specifically by securing their position. Hence, in promotions and appointments, many people obtain their roles not because they are the most capable candidates, but because they are on the good side of the incumbent.

These insights extend to private firms, where managers also have an interest in appointing loyal followers. An academic survey found that a third of executives reported that this practice exists in their organisation (Zaman and Lakhani, 2024).

The challenge of intracoalitional entropy

How it cripples collective action

The fact that people are—or can be—playing their own game during collective action leads others, in anticipation, to be on guard. It reduces the trust that would otherwise help people move forward together. When trust is lacking, individuals engage in protective behaviour to prevent others from gaining personal advantages. This is a major source of dysfunction in collective endeavours, often described as “division” or “lack of cohesion”.

Low-trust situations can be very stable: when people don’t trust each other, they rationally take steps to protect themselves—actions that can conflict with the interests of others. This, in turn, justifies others’ lack of trust. A low-trust situation with high entropy (people prioritising their own interests above all) is, in game-theoretic terms, a possible equilibrium of the social game.

Can we coordinate ourselves to efficiency?

But high-trust situations with low entropy—where people are united in working toward the collective goal—are also possible equilibria.5 A key challenge for any group is therefore to coordinate on a cohesive, high-trust equilibrium.

This is why employees spend so much time in “bonding sessions” of all kinds, why group documents and speeches go over the top in praising how “awesome” everyone is and how well the group is working, and why political organisations keep insisting to their members that collective action pays. If things were going so well on their own, we wouldn’t need to talk about it constantly.6

Two factors are key in determining whether groups manage to be cohesive or not.

Leaders

Leaders are a key part of the equation. Part of their role is to coordinate members’ beliefs in order to reach a more efficient and cohesive, high-trust equilibrium. Good, charismatic leaders manage to get people willing to work together toward a common goal, while dysfunctional groups often have leaders who are unable to generate such a feeling of mutual trust.

The collective stakes

The second factor is the stakes of collective action—how important it is for the group to work efficiently. If the stakes are high, people naturally tend to pull their weight for the group. If your plane lands on a desert island and your only chance of being rescued is to build a large fire for passing planes to see, chances are that most people will actively help gather wood.

In reality, what tends to make the stakes high is competition with other groups: tribes fighting wars, firms competing for market share, political parties competing for voters. A key factor that makes a group cohesive is therefore whether it is in conflict with another group. Our psychology is certainly shaped to help us navigate these stakes, with feelings of group identity becoming stronger when our group is in competition with others.7

When groups face low pressure and low competition, however, it becomes harder to prevent internal tensions from taking over and for coalitional entropy to grow—making groups inefficient.8

Why we keep being disappointed in that fact

One often hears complaints about the fact that groups don’t work as intended. People are frequently disappointed about their organisation and its inability, in practice, to deliver on its purported goals.

This disappointment may reflect overly idealistic expectations about how groups should function. These expectations are likely shaped by the self-narratives generated by groups, which focus on unity and collective achievements, while leaving the messy internal realities largely undiscussed.

There is always a gap between how a group claims to operate and how it actually does, because individual incentives are not perfectly aligned and lead people to follow their own paths. Perfect group cohesion is therefore an unachievable fiction.

Appreciating that internal tensions within groups are an inescapable aspect of human social behaviour helps us focus on workable strategies for managing and easing these tensions, rather than relying on idealistic and misguided suggestions (e.g. the idea that we should all simply adopt a positive mindset).

Groups do not work as well as they claim to. If you are disappointed by your company, your political party, or your sporting association, it most likely stems from the—inescapable—internal conflicts of interest and how they shape everyone’s behaviour. The key to group cohesiveness is not to call on people to “do better,” but to shape the structure of incentives and beliefs in a way that minimises the unavoidable intracoalitional entropy.

Understanding the messy nature of collective action is part of the hidden curriculum of social life. We have to learn, through experience, that when you zoom in on the internal life of a group, the officially well-behaved and well-defined Newtonian mechanics of solid social bodies gives way to the quantum chaos of individuals with misaligned interests.

References

Acemoglu, D., Egorov, G. and Sonin, K., 2008. Coalition formation in non-democracies. The Review of Economic Studies, 75(4), pp.987–1009.

Egorov, G. and Sonin, K., 2011. Dictators and their viziers: Endogenizing the loyalty–competence trade-off. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(5), pp.903–930.

Gauriot, R. and Page, L., 2015. I take care of my own: A field study on how leadership handles conflict between individual and collective incentives. American Economic Review, 105(5), pp.414–419.

Holmstrom, B., 1982. Moral hazard in teams. The Bell Journal of Economics, 13(2), pp.324–340.

Ke, C., Morath, F., Newell, A. and Page, L., 2022. Too big to prevail: The paradox of power in coalition formation. Games and Economic Behavior, 135, pp.394–410.

Lazear, E.P., 1995. Personnel Economics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Machiavelli, N., 1532. The Prince. Translated by G. Bull. London: Penguin Books, 2003.

Maner, J.K., 2017. Dominance and prestige: A tale of two hierarchies. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), pp.526–531.

Nickell, S.J., 1996. Competition and corporate performance. Journal of Political Economy, 104(4), pp.724–746.

Olson, M., 1965. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rabin, M., 1993. Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. American Economic Review, 83(5), pp.1281–1302.

Talmadge, C., 2015. The Dictator’s Army: Battlefield Effectiveness in Authoritarian Regimes. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Vives, X., 2008. Innovation and competitive pressure. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 56(3), pp.419–469.

Wagner, A.F., 2011. Loyalty and competence in public agencies. Public Choice, 146(1–2), pp.145–162.

Zakharov, A.V., 2016. The loyalty–competence trade-off in dictatorships and outside options for subordinates. The Journal of Politics, 78(2), pp.457–466.

Zaman, H. and Lakhani, K.R., 2024. Determinants of top-down sabotage. Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Management Unit Working Paper, (25-007), pp.1–35.

The only way individuals would always collaborate in groups toward a collective objective is if there were no conflict between their individual interests—as is the case for ants, who have a high degree of genetic relatedness (75%), roughly halfway between that of sisters and identical twins.

Coalition game theory mostly ignores intracoalitional conflict because it assumes that coalitions form binding agreements. Whatever disagreement there might be between members is assumed to be settled by an agreement respected by all. In the real world, however, agreements are typically not binding. Some coalitions delay the decision of how to allocate the prize of victory among members until after the fact. Political coalitions, for instance, often postpone the allocation of political positions until after elections. Even when agreements exist, they are typically, to some extent, renegotiable (Acemoglu et al., 2008; Ke et al., 2022). As a consequence, intracoalitional conflicts is a key feature of real world coalitions.

Another example I discussed previously is how managers often use their positions to gain personal rewards that are not aligned with the organisation’s goals—such as higher income or increased prestige.

One of the most high-profile examples of this phenomenon was the infamous decision by British politician Boris Johnson to back Brexit, seemingly on a gamble that it would pay off most for his political career. In 2016, as the debate over the upcoming Brexit vote was taking shape, he wrote an opinion editorial supporting a Remain vote, with the following reasoned economic argument:

This is a market on our doorstep, ready for further exploitation by British firms. The membership fee seems rather small for all that access.

This op-ed, written for the Standard, was never published. Instead, Boris opted to back Brexit. History seems to have vindicated his strategy, in the sense that he became a natural leader for the Brexit side and later Prime Minister.

Psychological game theory—the branch of game theory that studies situations where people may have preferences over others’ beliefs—points to the multiplicity of equilibria in such settings. A situation can settle into either a positive reciprocity equilibrium (people are kind to each other, believing others will be kind to them) or a negative reciprocity equilibrium (people are unkind to each other, expecting unkindness in return) (Rabin, 1993).

It is unusual to have family dinners where parents keep repeating that everything is great and everyone is doing a terrific job for the family. They don’t need to say it—because even though there are conflicts within families, interests are much more aligned. There is much less need to coordinate beliefs in each other’s loyalty to maintain a high-trust equilibrium. Similarly, if ants could talk, they would surely never bother with “bonding sessions,” as bonding would come naturally to them.

I discuss this extensively in the chapter on social identity in Optimally Irrational, the book.

Leaders are not a solution here, because they are also players in the social game. In low-pressure environments, leaders have stronger incentives to pursue their own interests rather than those of the group. In economic domains, for example, firms in less competitive industries exhibit more managerial capture, with managers prioritising their personal interests over the company’s profitability (Nickell, 1996; Vives, 2008).

I deeply enjoyed reading this, but feel ambivalent toward its conclusion. External pressure and inter-coalitional competition is not the only main factors that impact group cohesion. Norms of cooperation usually enforced through gossip and reputational costs are another one. The exclusion of norms that guide long-term interactions can create a more pessimistic picture of coalitions which in turn can actually lead to a everybody for themselves narrative of social life and lower trust societies. Of course, use of gossip and reputational costs to discipline non-group aligned behavior is never perfect and can be abused. But it doesn't make it useless