Why you are frustrated by your organisation

How a simple economic concept explain why organisations are dysfunctional in so many ways

The 2014 Lego movie started with a catchy tune, Everything is Awesome, sung by happy and cheerful employees working together in a great and friendly workplace. The song’s exaggerated positivity of the song is humorous because, in one way or another, we have all encountered such overly emphatic enthusiasm in modern organisations. Yet, most often, beneath this veneer of positivity, the reality is less rosy.

The workplace honeymoon is only shortlived

People often mention the workplace honeymoon phenomenon—a period of heightened job satisfaction and motivation following one's entry into a new organisation. Yet there is also talk of a workplace hangover, a phase when disillusionment sets in as one grasps the actual mechanics of the organisation. One potential explanation for this dynamic could be hedonic adaptation; we become accustomed to positive changes over time. Consequently, no matter how appealing a new role might initially seem, we eventually habituate to it.

But another reason arises, I believe, from the mismatch between the official narratives promoted by the organisations we work in—concerning their mission and vision—and the way they actually operate. Modern companies do not merely sell products and services; they claim to care about their customers and about society at large. Public administrations and non-profit organisations are charged with providing public goods: the police aim to reduce crimes, schools offer education and care for children, and churches deliver spiritual guidance to believers. Organisations portray themselves as entities guided by their missions and fully committed to fulfilling them.

The reality of how organisations truly function is typically different. This disconnect is brilliantly illustrated by the show The Wire, characterised by its creators as a “treatise about institutions and individuals”.1 One key element of the show lies in the friction between those members of organisations who are genuinely committed to the institutional mission and the harsh reality of how these organisations often fail to meet these ideals. Police authorities may be more interested in appearing to be successfully tackling crime. Schools with challenging students may be content with the appearance of educating them—indeed, in one case, adjusting the classroom thermostat to induce drowsiness and reduce unruliness. Journalists who claim to provide information to the public may instead be motivated to capture immediate attention through simplified narratives, rather than offering substantive, well-researched content.2

The principal-agent problem

At the heart of these issues lies a common problem. Organisations portray themselves as unified entities, acting as though they were individuals. The police are tasked with solving crime; schools are here to educate children; this media company exists to inform the public. In this framework, the natural state of affairs is for people within these organisations to fulfil these goals. Only occasionally do some individuals deviate and engage in fraud or malpractice that runs counter to the organisation's objectives. The presumed remedy is then to replace these few bad apples with others who are more committed to the cause. In this perspective, the pursuit of the organisation's mission is the norm, and deviations are exceptions.

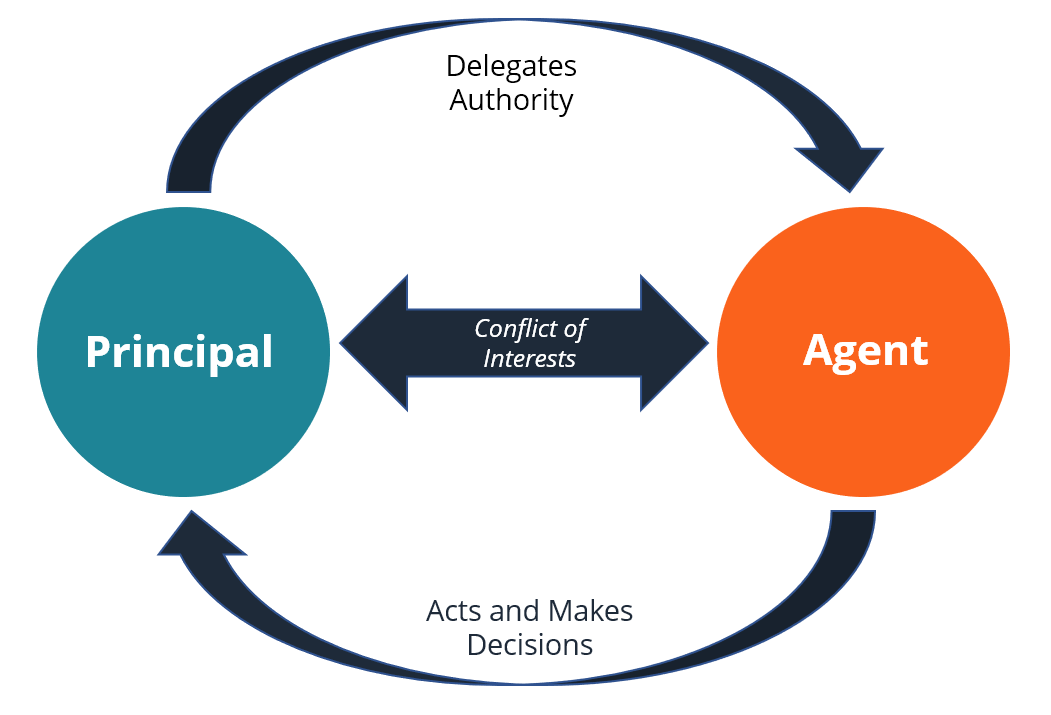

This vision is misleading. Organisations are not singular, coherent entities. Upon closer inspection, they dissolve to reveal webs of individuals with distinct goals, constraints, and beliefs, whose actions often conflict with the organisation's stated mission. One key insight from game theory and the economics of information is that when people have different incentives within organisations, it's simply not possible to align their actions fully with the organisation's goals. A reason for this impossibility is the Principal-Agent problem.

A principal-agent relation occurs when “one or more persons (the principal(s)) engage another person (the agent) to perform some service on their behalf which involves delegating some decision-making authority to the agent” (Jensen and Meckling 1976). The principal-agent problem arises from two aspects of this relation. First, the principal's and the agent's interests are typically not perfectly aligned. Second, the principal cannot perfectly monitor all of the agent’s decisions and whether they are justified. An important implication of these two points is that the principal is not able to make the agent always behave in the principal's interest without incurring some cost.

The principal-agent problem has frequently been used to describe the conflict between managers and employees whereby employees can have an incentive to shirk (Alchian and Demsetz, 1972). But managers are also agents of stakeholders: shareholders for firms, governments for administrations, and governments and private funders for non-profit organisations. These managers will have incentives to make decisions that benefit them more than they benefit the organisation they manage (Jensen and Meckling, 1976).

This idea was already suggested by Adam Smith:3

The directors of such [joint-stock] companies, however, being the managers rather of other people’s money than of their own, it cannot well be expected, that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private copartnery frequently watch over their own. Like the stewards of a rich man, they are apt to consider attention to small matters as not for their master’s honour, and very easily give themselves a dispensation from having it. Negligence and profusion, therefore, must always prevail, more or less, in the management of the affairs of such a company. - Smith 1776

Managers behaving badly

Personal gains

A substantial literature in economics has investigated how managers can extract rents (benefits) from companies, against the interest of shareholders (Edmans, Gabaix and Jenter, 2017). Part of managers’ remuneration can for instance be insensitive to performance by design, other parts may be hidden from shareholders, and perks can act as stealth remuneration that is hard to monitor.

Examples of managerial abuse are common. One of the most high-profile cases in recent times was the CEO of Nissan and Renault, Carlos Ghosn. He notably hosted his second marriage in the Palace of Versailles, indirectly utilising Renault's funds to help cover the expenses for the location. He was later arrested in Japan for underreporting his salary and misusing the company’s assets.4

Institutional reputation as a priority

Besides material interest, the fame and status of managers are associated with the public perception of the organisation they lead. Managers have therefore an interest in defending the public image of their organisation (towards their stakeholders and the public). When some indications arise that poor decisions or practices have occurred within the organisation, contradicting the organisation's stated mission, managers may prefer to suppress these concerns so as not to tarnish the organisation's image rather than address them.

History is ripe with examples of police forces covering for improperly conducted procedures and of churches having covered for criminal behaviour by some priests. A tragic example recently emerged in Britain in a different setting, a hospital. After several suspicious deaths of newborn babies, some doctors suspected a nurse of being responsible. When they raised the issue with their hierarchy, the hospital management did not report this accusation to the police but asked the doctors to apologise to the nurse. She was later found guilty.5

Another famous example illustrates this conflict between managers’ incentives and the mission of the institution. When in 1986, the engineer Roger Boisjoly advised his manager at NASA that launching the Challenger shuttle would be unsafe given the evidence that cold weather had degraded the O-ring seals on the solid rocket boosters, one manager reluctant to delay the shuttle’s launch told Roger: “Take off your engineer hat, and put your management hat on". The shuttle blew up 73 seconds after launch.

Timing of costs and benefits

The implications of the principal-agent problem go well beyond the rents that managers can secure from their positions. A misalignment of incentives between managers and stakeholders can lead to distorted decisions in terms of costs and benefits.

One of the biggest implications is the built-in incentive for managers to exhibit "short-termism." When managers must make decisions involving costs and benefits occurring both in the present and the future, they are inclined to prioritise decisions associated with immediate benefits and deferred costs, potentially occurring after the end of their tenure. Economist Jeremy Stein (1989) showed in a seminal paper that this is likely to happen even in private firms monitored by financial markets.

Short-termism can manifest as hyperactivity, where managers benefit from the appearance of doing something: “In the corporate sector, hyperactivity can be seen in frequent internal reorganisation, corporate strategies designed around extensive mergers and acquisitions, and financial re-engineering which may preoccupy senior management but have little relevance to the capabilities of the underlying business.” (Kay, 2012). Hyperactivity is even more likely to happen in organisations with short tenure and whose performance is not under the tough scrutiny of financial markets like administrations or non-profit organisations.

Preference for size over efficiency

Because company managers' pay—and likely their social status—are related to the size of their firm, they may have an incentive to “maximize, or at least pursue as one of their goals, the growth in physical size of their corporation rather than its profits or stockholder welfare” (Mueller, 1969). Several empirical patterns about mergers and acquisitions support this conjecture. Mergers tend to occur in waves, which may be explained by the fact that CEOs observing other companies merging may be incentivised to grow their own firms so as not to fall behind in comparison to other CEOs (Goel and Thakor, 2010). On the other hand, when CEOs are close to retirement, they are more likely to allow their companies to be the target of a takeover (Jenter and Lewellen, 2015).

In the context of public administrations, Niskanen (1971) famously posited that managers, who are not constrained by market forces, have an incentive to maximise the size of their administration.6 This idea was ironically described by the civil servant Sir Appleby in the classic British series, Yes Minister.

Distortion of management style: meetings and micromanagement

Other distortions can occur when certain activities possess a “consumption value” for managers, leading them to engage excessively in these activities to the detriment of organisational goals. For example, frequent meetings serve as prominent venues for the display and negotiation of status and power (Thomas and Allen, 2015).

Meetings are costly in terms of staff hours not devoted to other productive activities. Rogelberg et al. (2011) highlight that meetings account for around 7 to 15% of firms' budgets and are often considered unproductive by managers themselves. A survey of 76 companies that reduced meetings over the previous 14 months conducted by Laker et al. (2022) found increased productivity following the reduction in the number of meetings.

If the number of meetings is excessive, it may partially stem from managers enjoying them more than their staff do. This dynamic serves as a humorous element in the highly successful series The Office, which portrays managers as overly eager to command the attention of their employees.7

Another activity identified by economists as having a “consumption value” for managers is the ability to control decisions within the organisation (Bartiling et al., 2014; Ferreira et al., 2020). This propensity can lead to a reluctance to delegate and a tendency towards micromanagement. Micromanagement can decrease managers’ performance by leading to a misallocation of their time and attention.

Preference for loyalty over performance

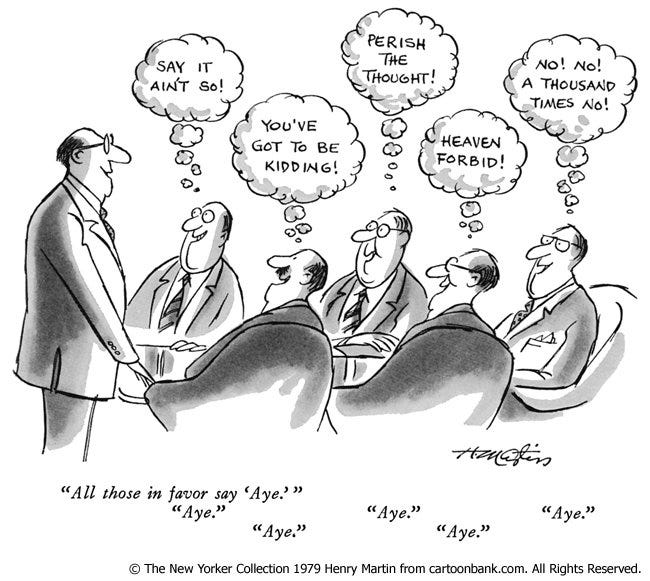

Managers' preferences may also diverge from those of stakeholders in the value placed on loyalty over performance. March (1962) argued in a seminal paper that a “business organization is properly viewed as a political system.” In such a system, leaders need to maintain control over a supportive coalition to secure the continuity and renewal of their tenure. From this perspective, leaders have a vested interest in surrounding themselves with loyal subordinates. They therefore face a “tradeoff between loyalty and competence” (Wagner, 2011). Managers may even hesitate to appoint subordinates who are too competent, fearing they could threaten their leadership (Glazer, 2002).8

Given managers' preference for loyalty, there is generally limited incentive for subordinates to “speak truth to power” by providing frank, albeit negative, feedback on managerial decisions and practices. On the contrary, aligning views with those of upper management is often rewarded with better prospects for future promotion within the organisation. This results in a tendency for managers to be surrounded by sycophantic “yes men”.

This incentive structure is inefficient. It hampers the truthful upward transmission of information from employees to higher management levels. Incentives for sharing candid, inconvenient information are limited. Rather, employees often engage in “upward management,” attempting to anticipate what management wants to hear and aligning themselves with that position.9

Managers also prefer that negative information—which could cast a poor light on their performance—be kept under wraps. Public criticisms by employees, including whistleblowing in extreme cases, often lead to adverse career consequences.10

These issues percolate throughout an organisation

These issues are not confined to top management behaviour; the insights from the principal-agent problem permeate the entire organisation, which is layered with managerial roles from top to bottom. Furthermore, organisations are composed of various departments, units, or groups that supply goods and services to one another in semi-contractual relationships. Therefore, principal-agent problems are pervasive within organisations, as these can be thought of as a network of contractual relationships, each with its own principal-agent problem.

Viewing the firm as the nexus of a set of contracting relationships among individuals also serves to make it clear that the personalization of the firm implied by asking questions such as “what should be the objective function of the firm?” or “does the firm have a social responsibility?” is seriously misleading. The firm is not an individual. […] we often make this error by thinking about organizations as if they were persons with motivations and intentions. - Jensen and Meckling, 1976

The misalignment of incentives can extend beyond individual actors to departments within the organisation, each with divergent cost and benefit considerations. For example, the marketing department may aim to maximise sales, while the legal department focuses on minimising potential legal complaints, and a consumer well-being unit is concerned with long-term customer satisfaction. These differing objectives can lead departments to operate in ways that are not fully cooperative.

Beyond these conflicts of interest, the ubiquity of principal-agent problems contributes to a lack of trust within organisations. This mistrust, in turn, promotes the development of costly bureaucratic procedures established to restrict the freedom of action of employees, preventing them from making self-serving decisions. These procedures however also limit employees' capacity to exercise their best judgement to make flexible decisions.

From workplace honeymoon to workplace hangover

Once you lift the lid of the “everything is awesome” narrative to look at how organisations really work, you find that they are riddled with managers at every level having misaligned incentives, a lack of flow of accurate information, tensions between the incentives of different departments, mistrust and creeping bureaucracy driven by lack of trust in organisation members.

New employees can understandably be somewhat naive about this organisational reality, placing excessive trust in the mission statement of the organisation they've just joined. The less-than-glossy aspects of the organisations are typically not advertised to applicants enticed to join the organisation.

This discrepancy between official narratives and actual practices leads to the aforementioned workplace hangover and frustration with an organisation that does not competently fulfil its stated mission.

To sum up, it is an inescapable truth that organisations’ inner workings are less ideal than what's publicly portrayed by their representatives. Internal conflicts, decision-making distortions, and bureaucratic inefficiencies arise at least in part from misaligned incentives and imperfect monitoring.

The good news is that knowing about this can help. It dispels the illusion that a few “bad apples” are the root cause of organisational issues. Instead, effective improvement must address the alignment of incentives, particularly between managers and the organisation's goals. A possible solution to mitigate dysfunctions is to include all relevant stakeholders in governance processes. Often, this should encompass employees, who are also invested in the organisation's mission. This perspective it challenges the assumption that managers are always the best champions of an organisation's objectives.

This post is part of a series on how economics and game theory help us make sense of a wide range of social behaviours. In previous posts, I wrote a quick introduction to game theory; I showed how it is strikingly effective at explaining tennis players’ strategies; how it helps us understand social norms; and how it helps to make sense of the regular cycles of petrol prices in many countries.

References

Adams, N.L., 2014. Why Did ‘Intelligence’ Fail Britain and America in Iraq?

Alchian, A.A. and Demsetz, H., 1972. Production, information costs, and economic organization. The American Economic Review, 62(5), pp.777-795.

Bailey, D.E. and Kurland, N.B., 2002. A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 23(4), pp.383-400.

Bartling, B., Fehr, E. and Herz, H., 2014. The intrinsic value of decision rights. Econometrica, 82(6), pp.2005-2039.

Bebchuk, L.A. and Fried, J.M., 2004. Pay without performance: The unfulfilled promise of executive compensation. Harvard University Press.

Cowgill, B. and Zitzewitz, E., 2015. Corporate prediction markets: Evidence from Google, Ford, and firm x. The Review of Economic Studies, 82(4), pp.1309-1341.

Edmans, A., Gabaix, X. and Jenter, D., 2017. Executive compensation: A survey of theory and evidence. The Handbook of the Economics of Corporate Governance, 1, pp.383-539.

Ferreira, J.V., Hanaki, N. and Tarroux, B., 2020. On the roots of the intrinsic value of decision rights: Experimental evidence. Games and Economic Behavior, 119, pp.110-122.

Glazer, A., 2002. Allies as rivals: internal and external rent-seeking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 48(2), pp.155-162.

Goel, A.M. and Thakor, A.V., 2010. Do envious CEOs cause merger waves?. The Review of Financial Studies, 23(2), pp.487-517.

Grinstein, Y., Weinbaum, D. and Yehuda, N., 2017. The economic consequences of perk disclosure. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(4), pp.1812-1842.

Hayes, R.H. and Abernathy, W.J., 1980. Managing our way to economic decline. Harvard Bus. Rev.;(United States), 58(4).

Jensen, M.C. and Meckling, W.H., 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics

Jenter, D. and Lewellen, K., 2015. CEO preferences and acquisitions. The Journal of Finance, 70(6), pp.2813-2852.

Kay, J., 2012. The Kay review of UK equity markets and long-term decision making. Final Report, 9, p.112.

Laker, B., Pereira, V., Malik, A. and Soga, L., 2022. Dear Manager, you’re holding too many meetings. Harvard Business Review, 100(5).

Lewin, L. and Lavery, D., 1991. Are Bureaucrats Budget-Maximizers?. Self-Interest and Public Interest in Western Politics.

Mueller, D.C., 1969. A theory of conglomerate mergers. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 83(4), pp.643-659.

Niskanen, J., 1971. Bureaucracy and representative government. Routledge.

Rogelberg, S.G., Shanock, L.R. and Scott, C.W., 2012. Wasted time and money in meetings: Increasing return on investment. Small Group Research, 43(2), pp.236-245.

Stein, J.C., 1989. Efficient capital markets, inefficient firms: A model of myopic corporate behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), pp.655-669.

Thomas, J.S. and Allen, J.A., 2015, January. Relative status and emotion regulation in workplace meetings: A conceptual model. In The Cambridge Handbook of Meeting Science (pp. 440-455). Cambridge University Press.

Wagner, A.F., 2011. Loyalty and competence in public agencies. Public Choice, 146(1-2), pp.145-162.

https://web.archive.org/web/20110928114544/http://dir.salon.com/story/ent/tv/int/2002/06/29/simon/index.html

Private companies that claim to care about more than just profits are often found wanting. For example, Qantas' commitment to its slogan has come into question following the COVID crisis. The airline illegally laid off 1,700 workers to preserve profits and faced lawsuits for failing to reimburse customers for cancelled flights.

It was pointed by Jensen and Meckling themselves. See my post on Adam Smith for more description of his criticism often leveraged at elites rather than at the lower class workers.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/07/business/carlos-ghosn-versailles-renault.html

Another tragic incident recently happened in France. When the parents of a bullied child sent a letter complaining to the regional educational department in France, they received a letter warning them of court proceedings against them if they were to continue to imply the department was not doing its duty. The child later committed suicide which led to a national scandal.

Niskanen certainly exaggerated the ability of public administration managers to maximise their budget since they face the oversight of politicians (Lewin, 1991). The principal-agent problem suggests, however, that this oversight cannot be perfect and that managers’ preferences can lead to oversized administrations.

The preference for meetings by managers is also supported by their reluctance towards employees working from home, associated with a loss of control (Bailey et al, 2020).

One manifestation of this preference for loyalty is the tendency for new managers to replace existing management teams with individuals they know and trust. This practice is encapsulated by the saying “a new broom sweeps clean.”

A documented example of such a process in politics has been the provision of slanted supportive evidence in favour of the Iraq war by the British intelligence to Tony Blair, as the administration was anticipating that it was the kind of information that was desired (Adams, 2014).

It is likely one of the reasons why corporate prediction markets, which aggregate employees’ information into a public prediction of the chance of success of specific projects, have not been more used by managers (Cowgill and Zitzewitz, 2015).

excellent article - wonder if you've ever heard of holacracy as an organizational structure, and what you might think of it? https://www.holacracy.org/

My organization tried it for a few years, I really liked it, but the structure didn't last and we reverted back to a more normal manager/employee relationship.

The article covers a very wide ranging subject well. With so many variables and multiple participants likely to cover their tracks, motives and activities statistical analysis of the most important variables is impossible. My experience of working globally, with large and small organizations in both the public and private sectors is that deviant managerial motives are the main issue. Greed, power and sex all feature. Management incentives are often such that they cause behavior contrary to the organizations stated aims and values. Organized labor can also become corrupted.