Why Kahneman's contribution to economics was so successful

Remembering Kahneman, economists' favoured psychologist

Kahneman, who passed away at the age of 90, had a tremendous influence on economics. Despite being a psychologist and an outsider to the discipline, his impact and contributions were recognised in 2002 by the award of a Nobel Prize in economics. He received this award for his work over many years with Amos Tversky, investigating the core assumptions economists used to think about how people make decisions.1 Their groundbreaking Prospect Theory has become the main alternative to the once uncontestable model of economic rational choice under risk used by economists. In this post, I revisit why and how Kahneman and Tversky’s work was so successful at upsetting the foundations of economics and becoming part of the mainstream views of modern economics.2

The undoing project

In his book The Undoing Project (2016), Michael Lewis describes the collaboration of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky and their methodical deconstruction of the standard economic approach to economic behaviour at the time:

The economists assumed that the agents in their models made the best possible use of available information. They assumed that when people made decisions, they had access to all the information they needed and that they used it. Danny and Amos showed that they often did not. - Lewis (2016)

Over the course of many years, Kahneman and Tversky progressively chipped away at the foundational assumptions of economic decision-making, gradually accumulating a wealth of experimental evidence against the model used by economists to describe a decision-maker, the homo economicus.

As a model of a person making decisions, the homo economicus has several main characteristics. First, it has consistent preferences. It is not the type of person who would buy something on the spur of the moment and regret it afterwards, nor would he repeatedly fail to keep on a diet he planned to follow or procrastinate instead of doing an important task. Second, the homo economicus is very good at maths, easily computing his foreseeable savings over the next five years—as a function of expected income raises, changes in inflation, taxes, and health insurance—without breaking a sweat. Third, he is self-centred: He is neither altruistic nor mean or spiteful; he just does not care about other people.3 To those finding his lack of care unkind, he’d just answer “it’s not personal, it’s business”. The homo economicus can be pictured as Mr. Spock in a suit: extremely smart but with questionable social skills.

The advantage of this model is that his decisions can be studied with mathematical tools. Since he always makes the best decision possible for himself, it is as if he were maximising a quantity that could be described as his subjective satisfaction.4

However, an obvious problem is that this model differs in meaningful ways from what we credibly and intuitively know about human psychology. When psychologists started investigating the hypotheses from economists, they easily collected contradicting empirical evidence from experimental studies. In his book Misbehaving (2015), Richard Thaler jokingly points out that his career progress benefited from having started at a time when economic models were clueless.

It was my good fortune that the models in economics were so bad that my discipline of psychology gave me special insights, ones that the clever economists had missed. Thaler (2015)

The secret of Kahneman and Tversky’s success

The importance of the influence of Kahneman and Tversky’s research can be easily conveyed by the number of citations their major papers have received. Most academic papers receive only a few citations. It has recently been estimated that the median number of citations for a paper in social sciences is 5 (Patience et al., 2017). In comparison, two of Kahneman and Tversky’s papers, published in 1974 in Science and 1979 in Econometrica, have received over 50,000 and 80,000 citations, respectively (as estimated by Google Scholar). Their Econometrica paper is the most cited paper in economics ever.

The Science paper famously presents a number of heuristics (rules of thumb) that Kahneman and Tversky argued we use instead of making fully calculated decisions. These heuristics have become well-known beyond academic circles. The representativeness heuristic involves judging the probability of an event based on how much it resembles a typical example, which can lead to neglecting prior probabilities. The availability heuristic refers to estimating the frequency or probability of an event based on how easily instances come to mind, which can be influenced by factors such as salience and recency. Finally, the anchoring heuristic describes the tendency to rely heavily on an initial piece of information (the “anchor”) when making estimates or decisions, even when the anchor is not directly relevant or informative.

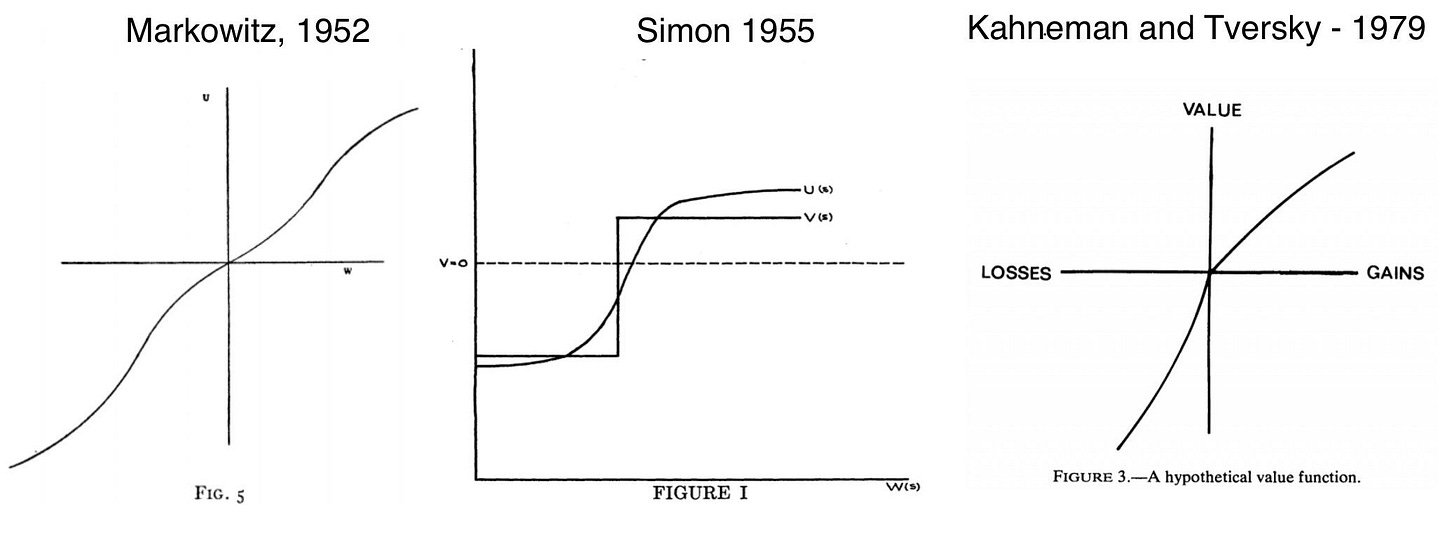

The Econometrica paper presented a series of observations about how people make decisions when choosing between risky prospects that contradicted the main economic model of rationality under risk: expected utility. To address these discrepancies, Kahneman and Tversky proposed two key modifications to the expected utility model. First, they suggested that our utility function is S-shaped around a reference point, meaning that we experience positive and negative subjective satisfaction relative to a subjective benchmark, often the status quo. Second, they proposed that we behave as if we were assigning greater weights to small probabilities (e.g., we overestimate our chance of winning the lottery) and smaller weights to probabilities close to one.5 These two modifications formed the basis of their new model, Prospect Theory, which could successfully explain the listed anomalies that expected utility theory struggled to account for.6

History: building on previous work

The reason for the success of Kahneman and Tversky's programme is not a reflection of their creation of radically new ideas. Indeed, the success of Prospect Theory has led modern generations of behavioural scientists to often ignore the intellectual history that preceded Kahneman and Tversky’s contribution and upon which they built.

The psychological investigation of economic principles can be traced back to Ward Edwards, a psychologist and son of an economist who decided to take economic assumptions seriously and study whether people respected economic predictions about how they make decisions or not.

It is easy for a psychologist to point out that an economic man who has the properties discussed above is very unlike a real man. In fact, it is so easy to point this out that psychologists have tended to reject out of hand the theories that result from these assumptions. This isn’t fair…. The most useful thing to do with a theory is not to criticize its assumptions but rather to test its theorems. If the theorems fit the data, then the theory has at least heuristic merit. (Edwards 1954)

Ward Edwards went on to supervise several psychologists who would spearhead the “Judgement and Decision-Making” field of research: Paul Slovic, Sarah Lichtenstein and Amos Tversky.

As part of this area of research, Kahneman and Tversky could observe many ideas being thrown around about possible psychological deviations from the canonical economic assumptions. The two central components from Prospect Theory, an S-shaped utility function and a probability weighting function, had been discussed before by different authors. In 1952, Markowitz had proposed an S-shaped utility around the customary level of wealth, which was overall steeper in losses. Shortly later, in 1955, Simon had proposed a step or S-shaped function around an “aspiration level”.

In regard to the probability weighting function, the fact that people seem to overweigh small probabilities was observed in an experiment by Preston and Baratta in 1948. In a discussion of possible subjective distortion of probabilities, Edwards had listed two solutions, with the one overweighting small probabilities being more likely. In 1977, Handa proposed a theory of such distortion to apply it in economic models.

A major contribution of Kahneman and Tversky was to select and refine some of the many ideas discussed at the time and provide a wealth of behavioural experimental evidence backing these specific features.

Methodology: The right number of steps ahead

To make contributions to their field, scientists want to propose new ideas a few steps ahead of the current consensus. However, to be successful, they also need to bring other scientists with them on their proposed path. If you go too many steps ahead, you won’t be followed by your peers; you’ll be a lone misunderstood genius possibly rediscovered later by future generations.

One of the reasons Kahneman and Tversky were successful is that they proposed a number of steps ahead that was large enough to be transformative but small enough for economists to follow them. While Prospect Theory was radical in undermining central principles shared by economists, it was not too radical for them. Kahneman and Tversky did not just destroy the economists’ intellectual toy (expected utility); they also provided a new toy they could use instead (Prospect Theory).

An essential aspect of Kahneman and Tversky’s critical contribution is that they did not reject the idea that people make calculations. Instead, their theory could be interpreted as reflecting the fact that people make calculations that deviate from the accepted principles of rationality. Kahneman and Tversky’s contribution was compatible with a fundamental methodological principle used in the discipline, utility maximisation (the idea that people choose the option that maximises their utility). Economists were able to use the theory with minimal conceptual retraining.

This aspect is a major difference from other criticisms of the homo economicus model that did not end up as impactful as Kahneman and Tversky’s. Herbert Simon won the Nobel Prize for his early work on bounded rationality in the 1950s. His notion that people do not maximise but only “satisfice” (choose a solution that is good enough) is often mentioned but rarely used by economists. Gerd Gigerenzer, a highly cited psychologist who worked on heuristics arguing that people do not optimise but use these rules to make quick and efficient decisions, has had a comparatively much smaller influence on economics.

A simple explanation is that both Simon and Gigerenzer likely went too far. By abandoning the idea that decision-makers make the best decisions (maximising some kind of utility), they threw away a foundational principle of economic methodology. Many economists may have agreed with their ideas but did not have ready-made ways to work with these ideas in new studies.

This reason for the success of Kahneman and Tversky can be seen in how their work was incorporated into economics. Their Science paper on heuristics is relatively rarely mentioned in economics. Their more formal theory in their Econometrica paper has, in comparison, been a blockbuster in economics. Notably, economists de facto stripped it of some of its psychological content. Kahneman and Tversky had included an editing phase in Prospect Theory whereby people map the choices they face into simpler prospects. This idea—hard to model in a mathematical way—pretty much disappeared from discussions about Prospect Theory. What remained was a set of formal principles that could replace those previously used in economics. The excellent book Prospect Theory by Peter Wakker shows the incorporation of these psychological ideas into a formal mathematical framework.

There is another way in which Kahneman and Tversky did not go too far. An interesting and often overlooked aspect of Kahneman and Tversky’s approach and the research program they initiated is that they implicitly retained the old normative assumptions from economics about what rational behaviour ought to be. The violations of economic rationality were discussed as practical limitations while the normative value of the principles was still largely accepted.7 While economists would have to agree their model of rationality was not descriptive (reflecting how people behave), they could still retain it as prescriptive (indicating how people should behave). In that context, the discovery of deviations from rationality paved the way for investigations about how to help people make better decisions in line with economic principles, through learning or nudging (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008).

What next?

Fifty years after Kahneman and Tversky’s Science paper, on heuristics and biases, behavioural economics has successfully transformed economics. In his 2015 presidential address to the American Economic Association, Richard Thaler stressed that behavioural economics is now part of the core of economics as a discipline. Its tools and concepts are consensual and routinely used in subfields like labour economics, development economics, political economy, and so on.

The undoing phase of the behavioural economic revolution has run its course. The next phase calls for redoing something different. Beyond the documentation of the deviations relative to the old economic hypotheses, economists are growingly interested in making sense of them and finding underlying unifying explanations of biases.

Merging novel insights from cognitive neuroscience and new developments in the economic theory of information, it makes sense to look for the functional origin of cognitive biases. In a complex world where information is rich but not free, behavioural mechanisms designed to help us make good decisions may produce features that look surprising when we ignore this complexity and the imperfect information we have when making decisions. Doing so will actually follow Kahneman’s view that the features of human psychology unveiled by psychologists and behavioural economists must be adaptive as good solutions to the tradeoff between the quality of our decisions’ outcomes and the cost (including time) to make these decisions.

The mind relies on these heuristics because they are fast, usually correct, and require little “computing” from the brain. They are a by-product of cognitive adaptation over deep time—over the millions of years of evolution. (Kahneman, 2011, p. 98)

In conclusion, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s work revolutionised the way economists understand decision-making. Their success stemmed from proposing transformative yet accessible ideas, building upon existing research, collecting a wealth of empirical evidence, and maintaining compatibility with economic principles. As economists continue to explore human behaviour, the next step is likely to investigate the adaptive nature of the biases and heuristics identified by Kahneman and Tversky, while integrating further the modern insights from economic theory with the empirical findings from other behavioural sciences.

References

Edwards, W. (1954) 'The theory of decision making', Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), pp. 380-417.

Handa, J. (1977) 'Risk, probabilities, and a new theory of cardinal utility', Journal of Political Economy, 85(1), pp. 97-122.

Kahneman, D., 1999. Objective happiness.

Kahneman, D., 2011. Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1974) 'Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases', Science, 185(4157), pp. 1124-1131.

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979) 'Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk', Econometrica, 47(2), pp. 263-292.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J.L. and Thaler, R., 1986. Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. American Economic Review, 76(4), pp.728-741.

Lewis, M., 2016. The undoing project: A friendship that changed the world. Penguin UK.

Page, L., 2022. Optimally irrational: The good reasons we behave the way we do. Cambridge University Press.

Patience, G.S., Patience, C.A., Blais, B. and Bertrand, F. (2017) 'Citation analysis of scientific categories', Heliyon, 3(5), p. e00300.

Preston, M. G. and Baratta, P. (1948) 'An experimental study of the auction-value of an uncertain outcome', The American Journal of Psychology, 61(2), pp. 183-193.

Quiggin, J., 1982. A theory of anticipated utility. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3(4), pp.323-343.

Simon, H. A. (1955) 'A behavioral model of rational choice', The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), pp. 99-118.

Thaler, R.H., 2015. Misbehaving: The making of behavioral economics. WW Norton & Company.

Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R. (2008) Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D., 1992. Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), pp.297-323.

Wakker, P.P., 2010. Prospect theory: For risk and ambiguity. Cambridge University Press. Markowitz, H. (1952) 'The utility of wealth', Journal of Political Economy, 60(2), pp. 151-158.

Amos Tversky died in 1996. It is commonly believed that he would have jointly received the Nobel Prize with Daniel Kahneman in 2002 if he had still been alive at the time.

Besides his contributions to the study of judgements and decisions about risk and probabilities which I discuss here, Kahneman also made significant contributions to the role of fairness in economic transactions (Kahneman et al., 1986) and about the drivers of happiness (Kahneman, 1999).

Economic theorists will, at this point, rightly point out that the core of the economic models did not require the decision-maker to be self-centred. However, in practice, it is an assumption that was widely associated with this model. I discuss this point in detail in Chapter 10 of Optimally Irrational (2023).

Economists chocking on their coffee while reading this and thinking about the ordinal nature of utility will, I hope, allow me some leeway to describe utility in these intuitive terms, particularly given that economists commonly discuss utility as a cardinal measure (Page, 2023). I personally think it is now reasonable to consider utility as a measure of subjective satisfaction.

To be precise, in their 1979 paper, Kahneman and Tversky assume the overweighing of small probabilities while being agnostic about what happens for very small probabilities close to zero. For these, they also considered the possibility that, in some cases, people could ignore them instead of overweighting them. In later work on Prospect Theory, this idea disappeared to let the place to the simple overweighting of small probabilities and even later to the overweighing of the (typically small) probabilities of extreme events (Quiggin, 1982, Tversky and Kahneman, 1992).

For the economist readers. Formally only the change in the role of probabilities deviates from expected utility. The suggestion that utility is S-shaped and reference-dependent is often considered in conflict with rationality for other reasons.

In the rationality wars, Gerd Gigerenzer famously criticised Kahneman and Tversky for this. He took the opposite view, arguing that people are making good decisions (they are not “biased”) and that the assumption of maximisation is unrealistic (economic principles are not good normative principles).