What is a Bias?

Are cognitive biases evidence of our flawed cognition?

I have written several posts revisiting classical biases, challenging the prevalent assumption in behavioural economics that they are cognitive blunders. I have argued that in some cases, these “biases” can be explained as being an adaptive solution given the irreducible biological constraints our perceptual system faces. However, if a behavioural pattern is optimal under some biological constraints, does it necessarily mean it is not a bias? This leads us to an essential question: What is a cognitive bias anyway?

Bias relative to a norm

Many debates on the meaning of a given term take the form of discussions about what is its “true” definition. The definition of a term is a social convention, so instead of looking for the true definition of bias, let's focus on its common interpretation. The Encyclopedia Britannica defines “cognitive biases” as “systematic errors in the way individuals reason about the world due to subjective perception of reality.”

The accepted definition of bias therefore relies on the notion of error. An error, in turn, requires a comparison to something deemed correct. When we consider perception, an objective reality exists outside our senses. A visual illusion can for instance be characterised as an error of perception due to the discrepancy with objective reality. This discrepancy, then, constitutes a cognitive bias.

But what about decisions stemming from personal preferences? Talking about bias when making decisions means that we should be able to define what’s the right decision. But what is it? Once you start thinking about it, you realise it's a challenging question.

The work of Kahneman and Tversky laid the groundwork for a research program termed “heuristics and biases”, which can be seen as the precursor to behavioural economics. This research program emerged in opposition to the principles of rational behaviour assumed by economists. Economists made assumptions about how people would act if they were rational, and typically believed that these principles provided a good description of real-world behaviour. It is this supposition—that people are rational in practice—that psychologists and behavioural economists systematically dismantled. However, an interesting and often overlooked aspect of Kahneman and Tversky's approach and the research program they initiated is that they implicitly retained the old normative assumptions from economics about what rational behaviour ought to be.

But, are the principles of rationality derived from the traditional economic approach a good norm? I addressed this issue comprehensively in a chapter of my book “Optimally Irrational”. In short, the question of what should be the principles of “rationality” is anything but simple.

What is a good decision?

A good point to start is to consider a rational decision as a decision that aligns with your plans and goals. One method to verify whether a decision-making process leads to rational outcomes or errors is to check whether it aids people in achieving their desired ends. However, this prompts another question: What do people want?

One possibility is that people seek satisfaction in the form of pleasure and happiness. Therefore, good decisions would be those that optimise your pleasure and happiness. From this perspective, you commit mistakes when your decisions lead to lower satisfaction. This view might initially seem plausible, but upon reflection, it's not as straightforward as it appears. Consider people who set challenging goals for themselves, like running a marathon, climbing a challenging mountain, or merely trying to beat their personal best in their weekly sporting exercise routine. Why not just enjoy a movie at home with some popcorn instead? It seems a much less painful activity. These examples illustrate that people often purposefully engage in activities typically associated with negative experiences, ranging from swimming in freezing water to watching horror movies. Paul Bloom elaborates on this in his book The Sweet Spot.

Another telling fact is that people typically reject the idea that they would want to maximise personal satisfaction. The philosopher Robert Nozick famously proposed the following thought experiment:

Suppose there were an experience machine that would give you any experience you desired. Superduper neuropsychologists could simulate your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book. All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain. Should you plug into this machine for life, preprogramming your life’s experiences? - Robert Nozick (1974)

This “experience machine” was de facto depicted in the movie Matrix, where humans are plugged into a machine, experiencing sensations indistinguishable from real life. In a famous scene, one character, Cypher, chooses to betray his friends and join the machines' cause in exchange for a life filled with pleasurable (simulated) experiences. To most people considering the experience machine, opting to live in it seems wrong.1 And Cypher’s decision hurts our intuitions about what we should do in that situation.

So if not satisfaction, could there be some higher objective that defines a good life? This notion has been echoed frequently throughout history. In the Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle contended that a good life is not achieved by merely pursuing pleasures.

Most men, and men of the most vulgar type, seem (not without some ground) to identify the good, or happiness with pleasure… the mass of mankind are evidently quite slavish in their tastes, preferring a life suitable to beasts. - Aristotle

In this perspective, there may be superior types of satisfaction, such as intellectual, moral, or aesthetic satisfaction, which are more worth pursuing. Perhaps we should chide Ann for her fondness for catchy Taylor Swift songs over classical opera. Likewise, maybe we should reproach Bob for his enjoyment of light-hearted TV comedies, while being oblivious to the works of Goddard, Pasolini, and Wong Kar-Wai. But if Ann and Bob's personal satisfactions aren't what determine whether they're making good decisions, what ultimate goal should they be striving for to lead a “good life”? More importantly, who should be the judge of whether they are making the right decisions for themselves? There are no straightforward answers to these questions.

Economists chose to sidestep such considerations, defining rational decisions not by people's objectives, but by their consistency. From this perspective, people can aim for whatever they want. No preference is inherently rational or irrational: if Ann chooses a low-paying job at an NGO while Bob opts for a high-income position at a hedge fund, neither is more rational than the other. They simply have different preferences. To put it briefly, one doesn't question the content of people's tastes, the only requirement is that they are not inconsistent. One principle of consistency is that there is a sensible order in your preferences. If you're in an ice cream shop and you prefer banana over chocolate, and chocolate over vanilla, then you should also prefer banana over vanilla. This particular principle is known as transitivity and seems reasonable. But, one might question why it's necessary for individuals to abide by these consistency principles. What's wrong with not adhering to these principles? It is true that if people maximise their satisfaction, then, by design, their choices follow rules of consistency.2 But, if maximising satisfaction isn't your goal, why should consistency be a primary goal to evaluate whether your decision-making process is good or not?3

Even if we were to agree that “consistency” is the hallmark of rationality, why would it take the form of the specific principles proposed by economists? Another one of these principles is for instance the independence axiom, a key assumption underlying what economists have considered as rational decisions under risk.4 If people follow this principle and a few others, including transitivity, then they choose between risky prospects as if they were ascribing subjective values (utilities) to possible outcomes and they were selecting the prospects with the highest expected utility.

The term axiom means “self-evidently true”. So, it's somewhat ironic that it took several months for prominent economists, Marschak, Friedman and Savage, two of whom were later awarded the Nobel Prize, to convince another Nobel Prize winner, Samuelson, that the axiom of independence should be a principle of rationality. In addition, you may be surprised to learn that a critical argument in that discussion was how people should react when facing a prospect that could lead to getting either a beer or some pretzels.5 This axiom, which required substantial deliberation from brilliant minds to reach a consensus, was later propagated to generations of economists as an obvious principle of rationality.

In fact, Samuelson was not the only one to find this principle not straightforward. Most people do! When asked to make risky choices, the majority of people violate the independence axiom, and even after economists painstakingly explain the significance of this principle, a considerable portion of respondents replies, "Thanks, but I'll stick to my choices." Reflecting on this inconvenient fact, decision theorist Itzhak Gilboa points out that if people consciously choose to disregard the axioms established by economists, then the status of these axioms as reliable principles defining good decisions becomes problematic:

If […] people shrug their shoulders when we explain the logic of our axioms, or admit that these are nice axioms but argue that they are impractical, we should better refine the theories. - Gilboa (2009)

Thus, it isn't straightforward that traditional economic theories provide a definitive normative benchmark for rational behaviour. By this, I don't imply that this framework is outright wrong. In many instances where the decision-maker's objectives are simple and clearly defined—such as earning more money—these assumptions may be valid as normative principles we ought to follow. However, in many cases, it is not clear whether the economic principles of rationality reflect the right way for people to behave to make “good” decisions. Nonetheless, it's these theories that Kahneman and Tversky retained as a normative benchmark. Consequently, the questions about the validity of this benchmark also call into question whether deviations from this benchmark should necessarily be regarded as biases.

Revisiting biases

Due to a focus on critiquing the standard economic model of rationality, the search for “biases” in the field of behavioural economics has likely gone too far. In the last three posts, I revisited three classical “biases”. Through these specific examples, these three posts illustrate different ways in which cognitive biases may often not deserve such a label.

Some biases can be spurious findings

First, I showed how the hot hand fallacy (the belief that basketball players can become more successful after scoring a few throws) was actually not a fallacy at all and is a real phenomenon. In the hunt for biases, behavioural economists and psychologists have occasionally too swiftly presumed that peculiar behaviours were mistakes. Gigerenzer has, certainly with some deliberate irony, dubbed the overemphasised propensity to search for cognitive biases the “Bias bias”.

In the case of the hot hand, the empirical evidence was weak to start with but the “discovery” of this fallacy fitted so seamlessly into psychological explanations of a potential bias in the perception of random events that the notion that the hot hand was a fallacy became one of the biggest hits in behavioural economics. More than 30 years later, a reappraisal of the empirical evidence found that the hot hand was not a fallacy (players indeed tend to get better after several successes).

Some biases are good solutions once the decision problems are well understood

Second, I showed how the confirmation bias—“the search for information that confirms your hypothesis” (Klein, 2017)6—is credibly not a bias at all but an optimal solution to the problem of searching for information when information is costly.

This case illustrates that, in some instances, patterns of behaviour are only puzzling because the researcher may not have an adequate understanding of the actual decision problems people face. In many old models, economists assumed that people could access and process information at no cost and that they had, therefore, perfect information. More recent models that reflect the fact that information is costly to acquire and process, often show that what seemed puzzling and had been labelled a bias, is actually an optimal solution to the more intricate problem we face when information is costly.

Some biases are optimal solutions (under biological constraints) of the evolutionary process

Finally, I showed how the S-shaped value function from Prospect Theory—the idea put forward by Kahneman and Tversky that satisfaction is a function of gains and losses relative to a subjective reference point—is credibly an optimal solution to the problem of perception of subjective value once we take into account that our perceptual system is limited in the magnitude and precision of the signals it can produce.

Biases?

The first two “biases” can clearly be reconsidered as not being “biases”. They are not errors. The last one, however, faces the counterargument that optimal solutions under biological constraints can still be deficient.

Nevertheless, here again, we have to contemplate what is the norm we are comparing humans’ behaviour and perception to. If the benchmark is a perfect decision-maker with flawless and costless perception, it may not be useful to characterise whether humans are good at making decisions because, obviously, we will fall short of that benchmark.

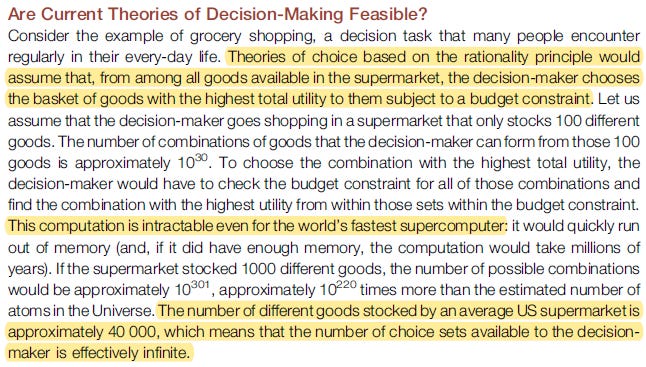

Some of the tasks assumed to be achieved by rational decision-makers in the old economic models are just beyond the reach of possibilities. Take, for instance, the assumption that people should be able to quickly choose between any possible basket of goods in a supermarket, without facing any costs of any kind such as thinking time or cognitive effort. The number of such baskets is mind-blowing large, indeed it is much (much!) larger than the number of atoms in the universe (Bossaerts and Murawski, 2017). Is it a reflection of cognitive flaws if actual human consumers sometimes struggle to ascertain what selection of goods they really prefer?

Given the time and cost to process information, perfect decisions are often not feasible. That being said, given our biological constraints, human cognition is typically well-designed for us to make good decisions most of the time. The comparison with optical illusions is again relevant. These are not bugs, but features of our visual system that is very efficient at recognising objects, their location and their motion in everyday life. Optimal illusions arise as “edge cases” which are the costs we have to pay for our visual perception to be very quick and correct most of the time. Focusing on these errors, as if they were deficiencies, may not be helpful to understand our visual perception system.

Similarly to optical illusions, cognitive biases are likely edge cases. Many of them have been isolated in carefully crafted situations set up in laboratory experiments. Such edge cases are however not representative of how we make decisions most of the time. In his famous book Sources of Power, Gary Klein stressed that contrary to the view coming from laboratory experiments, people are often excellent at making decisions in real-world situations.

Naturalistic decision-making researchers are coming to doubt that errors can be neatly identified and attributed to faulty reasoning… If we try to understand the information available to a person, the goals the person is pursuing, and the level of experience, we will stop blaming people for making decision errors. No one is arguing that we should not look at poor outcomes. The reverse is true. The discovery of an error is the beginning of the inquiry rather than the end. - Klein (2017)

Behavioural economics has been extremely successful at repelling the overly simplistic vision of the rational decision-maker used in economics. But the momentum of the discipline has certainly pushed the field too much in the other direction, systematically looking for flaws in human cognition. By looking at the good reasons behind the surprising and puzzling aspects of behaviour we’ll understand better why we behave the way we do. Doing so, we are not going to overturn the gains from behavioural economics and go back to the old model of economic rationality, but we’ll enrich further our understanding of human behaviour.

What next? I could go on looking at biases. That is fun and there is plenty of material there, but that would make this Substack a bit mono-dimensional. I’ll come back to biases, but the next few posts will look at another interesting area: the uncanny ability of game theory to explain the world.

References

Bloom, P., 2021. The Sweet Spot. Ecco.

Bossaerts, P. and Murawski, C., 2017. Computational complexity and human decision-making. Trends in cognitive sciences, 21(12), pp.917-929.

Eil, D. and Rao, J.M., 2011. The good news-bad news effect: asymmetric processing of objective information about yourself. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 3(2), pp.114-138.

Gigerenzer, G., 2018. The bias bias in behavioral economics. Review of Behavioral Economics, 5(3-4), pp.303-336.

Gilboa, I., 2009. Theory of decision under uncertainty (Vol. 45). Cambridge university press.

Klein, G.A., 2017 (first edition 1998). Sources of power: How people make decisions. MIT press.

Moscati, I., 2016. Retrospectives: how economists came to accept expected utility theory: the case of Samuelson and Savage. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(2), pp.219-236.

Nozick, R., 1974. Anarchy, state, and utopia. John Wiley & Sons.

In the case of transitivity, if the satisfaction derived from banana exceeds that from chocolate, and chocolate's satisfaction exceeds vanilla's, it's logical to presume that the satisfaction from banana would exceed vanilla's, leading you to opt for banana between the two.

To many economists, this question will seem outrageous. But I’ll argue that it is the case, because the assumption that straightforward principles of consistency define good decisions has been drilled down into young generations of economists for decades without further discussion. In fact, all the foundational principles of rationality are questionable and have been questioned, often by the very same person who proposed the principle in the first place. The case of transitivity is an excellent example. Discussing this principle, the economist Paul Anand stated “Whether rational preferences must always be transitive is a normative question… “the modern view”… holds, simply, that it is perfectly possible for rational agents to have intransitive preferences” (2009).

The axiom of independence roughly says that the utility for bundles of risky prospects should be independent of the prospects these bundles have in common. So your preference between two bundles should stay unchanged if a prospect present in both bundles is changed for another prospect. For instance, consider the situation where two job offers: A and B both feature a 50% probability to be promoted within 2 years. If you prefer job offer A (given all its other characteristics), you should still prefer A if the probability of promotion drops to 0% in both A and B.

Marschak considered a man who is indifferent between beer and tea. Under the independence axiom, this man should also be indifferent between a lottery giving either beer or pretzels and another lottery giving either tea or pretzels. Marschak wrote: “I should not expect…[the] man to tell me that the mere co-presence in the same lottery bag of tickets inscribes ‘pretzels’ with tickets inscribed ‘tea’ will contaminate (or enhance) the enjoyment of either the liquid or the solid that will be the subject’s lot” (cited in Moscati 2016).

Some readers pointed to the fact the term confirmation bias is also used to refer to the discounting of contradictory information. This version of the “confirmation bias” which is not the one I considered is also called de minimus (Klein 2017), or the good news/bad news effect (Eil and Rao 2011).

Absolutely, "bias" is clearly a wrong term. Evolution shaped our decision making circuitry to make *repeated* fast life and death decisions in the conditions of uncertainty, rather than one-time slow low-risk optimal decisions with perfect information.

Thank you for an excellent post. Very clear explanation that connects different, well-known perspectives. One question, if I may, concerning footnote 6: I appreciate your distinction between the different perspectives on confirmation bias. I wonder, however, if "discounting of contradictory information" is an implicit feature (or at least risk) if one mainly searches for information that supports one's hypothesis? As I read it, your core definition focuses on the nature of information search (and how this can be optimal), but it is also associated with the risk of not finding out that the hypothesis is wrong - something one might have discovered if one had searched for opposing info. I also wonder if you have listened to Daniel Laken's podcast (episode 3) on confirmation bias, where they discuss Wason's "confirmation bias" card experiment. They acknowledge both perspectives on confirmation bias (at least implicitly) but also highlight that in some situations it might be better to try to "disconfirm" a hypothesis.