The reality of our "influence" on social media

How social media platforms flatter us to keep us on them

For many generations, most French kids have been exposed at school to one of Aesop's fables, The Crow and the Fox as written in rhyme by 18th-century poet La Fontaine. The story famously presents a fox who compliments a crow about the beauty of his coat, comparing it to a phoenix. Flattered, the crow opens its beak, letting drop the cheese he was holding. The fox, whose intention was only to grab the cheese, concludes dryly:

The flatterer, my good sir,

Aye liveth on his listener;

Which lesson, if you please,

Is doubtless worth the cheese.La Fontaine (1668) translated by Elizur Wright

This tale was certainly socially incisive at a time when King Louis XIV was building a royal court where aristocrats often competed in flattery to gain his favours. The popularity of this tale, in France and beyond, reflects the concern that flattery is a common way to take advantage of us.

In this post, I look at a specific illustration of this principle: how social media platforms flatter our sense of importance by inflating our feeling of social influence on their platforms.

“Influencer”, the new dream job

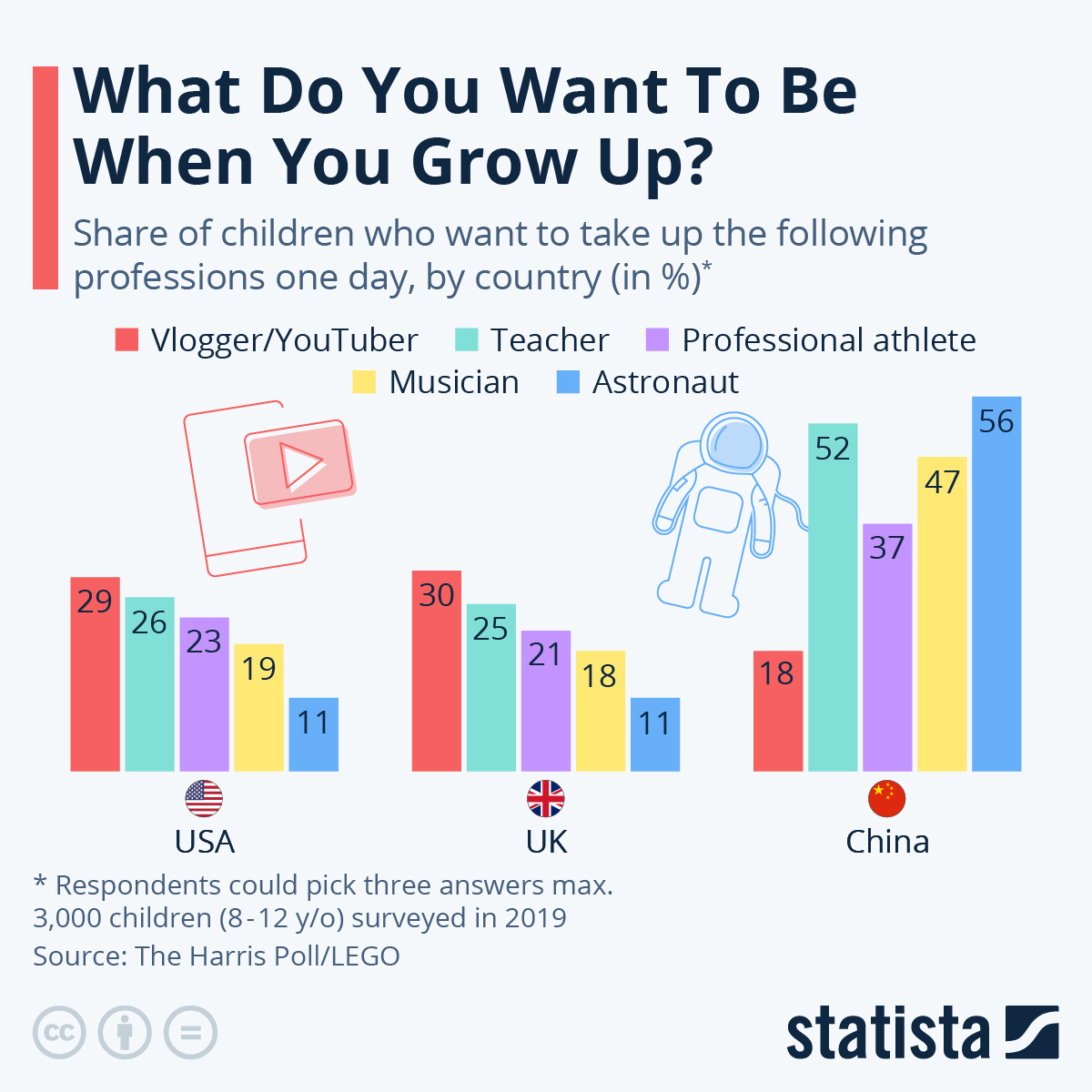

Surveys of young people’s aspirations suggest that those living in Western countries now aspire to become social media influencers as a profession.

These dreams may be understandable, but they may also be the result of some biases in the processing of information. First, many people you see on social media are likely to be famous, because famous people are selected by the algorithms to be broadcasted to a larger number of people. It is an example of survivorship bias. It may give the wrong impression that it is easy to become famous on social media since a large proportion of who you see there has a large audience.

Second, the information we get from social media platforms—in particular, how popular our contributions are—is not necessarily impartial. These platforms have an interest in motivating us to stay on them. It may be in their interest to tell us that what we post matters.

What is a “view”?

The example of Twitter views

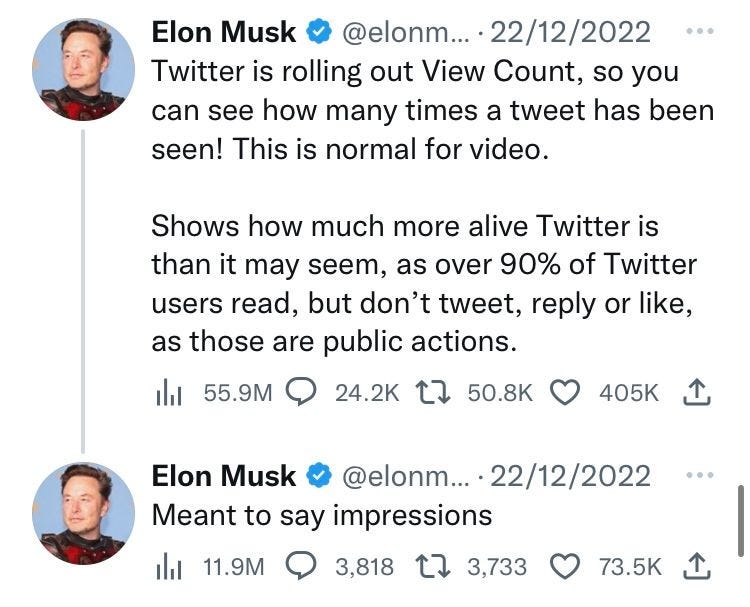

After Elon’s takeover of Twitter, one of the changes was making the number of views of posts visible. Elon justified the move because “90% of Twitter users read, but don’t tweet, reply or like,” so the real number of people seeing what you post is much larger than the few who publicly interact with your post.

One likely intended effect is to let posters know that their contribution is reaching more people than they thought. In a reply to Elon, user Karim Jovian expressed this feeling, with a tweet that received only 6 likes but was seen nearly a thousand times!

But wait a minute, can the maths stack up if we all get tons of views? Where are all the people out there seeing what we post?

The example of Substack

Substack is another platform where we can get an audience. They provide writers with quite a bit of information on a dashboard. In Substack's presentation of this feature, they give the following example:

For my last post, it indicates more than 2,000 views! For an academic who spends years writing papers usually read by a narrow circle of experts, that’s a step up in readership!

What is a “view”?

As we progressively cool down from the excitement of having such a social reach, one question may arise in our heads: “What is a ‘view’ exactly?” You suddenly notice that Elon’s second tweet requalified the term view as “impression”. Why is that?

The game theory of disclosure games

Over the last two posts, I have discussed how situations where we exchange information can be seen as communication games. In these games, people can mutually benefit from exchanging information. They may have an interest in being truthful in what they say in order not to lose the trust of others. This view explains why the trustworthiness of statements varies across settings like science and politics because of their different reputational incentives.

One type of communication occurs when somebody has some information and can decide to reveal it, or not, to somebody else. Game theorists have named such situations disclosure games. They are the game we play when writing up our CV, when a restaurant decides whether to put its hygiene rating on the wall or when a company decides to reveal or not the results of an external audit.

In a disclosure game, the sender of information often has different incentives than the receiver. When John (sender) writes his CV, he wants primarily to get the job he is applying for. The recruiter (receiver) only wants to hire John if his track record indicates he will work well in the position. Suppose John lost his previous job after a conflict with his manager. It is a piece of information that the recruiter may find interesting but that could hurt John’s chances. He may therefore prefer to leave it out of his CV and interview answers. The recruiter knows that it is John’s motivation to leave out possibly inconvenient details from his CV, so many of the recruiter’s questions may be to try to suss out the relevant information that is missing.

From information unravelling to obfuscation

Because the sender and the receiver have different incentives, the receiver may reasonably doubt whatever the sender gives as “information”. If this information is non-verifiable and the sender can lie the outcome can be a babbling equilibrium: no information is exchanged as the receiver does not believe a word of the sender.

But if the information is verifiable—when it is impossible or too costly to lie—something interesting happens: senders may have an interest in being truthful! Imagine that John passed a standardised test relevant to the job he is applying for. The test result is verifiable from John’s official transcript, so John cannot lie. Would he include his test results? For simplicity imagine there are three bands of results: good, average, and fail. If John’s results were good, he should definitely include them. By doing so, he indicates that he is not in the lower categories. But consider Jack whose test result was average. He knows that those with good results are putting it on their CVs. So if he doesn’t include his result, the employer will think that it was either average or fail. Since Jack has not failed he should make sure to let the employer know that by including his result. The employer ends up with full information: those with good and average results say it, and those who do not say anything are those who failed the test. This automatic process of information revelation is called information unravelling.1

But that scenario only occurs when the information is fully verifiable and not too costly to acquire. It also requires the receiver to know the relevant pieces of information the sender could send or not. When these conditions are not met, the sender will typically have an interest in withholding very bad news and reporting only relatively good news (Milgrom, 2008). He may have all the more incentive to do so because—in experiments on disclosure games—people have been found to be “insufficiently skeptical about undisclosed information—the extent to which no news is bad news.” (Jin et al., 2021).

In the example of John writing his CV, the employer may not be sure whether John took the test or not. In that case, John can include the test result if it is good and leave it out if it is bad. When the employer does not see a test result in John CV, they won’t know whether John got a bad result (and tries to hide it) or whether he simply never took the test.

This can explain why businesses selectively provide consumers with information that looks good for their products. They do so because it works, either because consumers do not know what other (potentially less favourable) information the business could have provided, or because they do not discount enough the business’ messages as being strategically selected.

In the case of social media, the platforms want us to spend our time on them. Social media companies can provide us with only good news (e.g. “impressions”), leaving bad news (e.g. actual engagement) out. A key insight from the study of disclosure games is that, even if we are not totally naive, it can work and influence our beliefs because we do not know exactly all the information they could provide us.

The information the social media don’t give you

Twitter and reads

How long do people look at your post, and what is the bot-free number of views? We can actually use Elon’s tweet to make an estimation. If Elon is right that 90% of Twitter users “read” but do not interact, then we should observe 10 interactions for 100 reads. With Elon’s assumption, the 405 thousand likes on his tweet would come from… around 4 million readers, ten times less than the 55.9 million “impressions” indicated in his tweet.2

Perhaps Elon’s 90% estimation of the proportion of readers who interact is wrong. To estimate it, I posted the tweet below asking people how often they like tweets. From this, we can estimate the average proportion of tweets that people like: roughly 3% in my sample.3 So it means that when a tweet is read, the reader does not like it 97% of the time on average. With such an estimate, the number of people who read Elon’s tweet should be around 13.4 million only a quarter of the 55.9 million indicated.4

The number of “impressions” indicated by Twitter is therefore likely to be substantially larger than the number of readers. It may include impressions induced by bots and users seeing the tweet several times.

Substack and audience retention

Substack also gives you a number of views. However, Substack posts are long. This one is more than 2,000 words. What’s the proportion of people who actually read the whole post?

It is a fair question to ask. YouTube provides information about audience retention to its posters and it is often very low. In the example below, on a 7:26 video, only 40% are still watching after 30s and something like 10% are still watching at the end. There is therefore a substantial difference between the number of “views” and the number of people who actually watched the whole video.

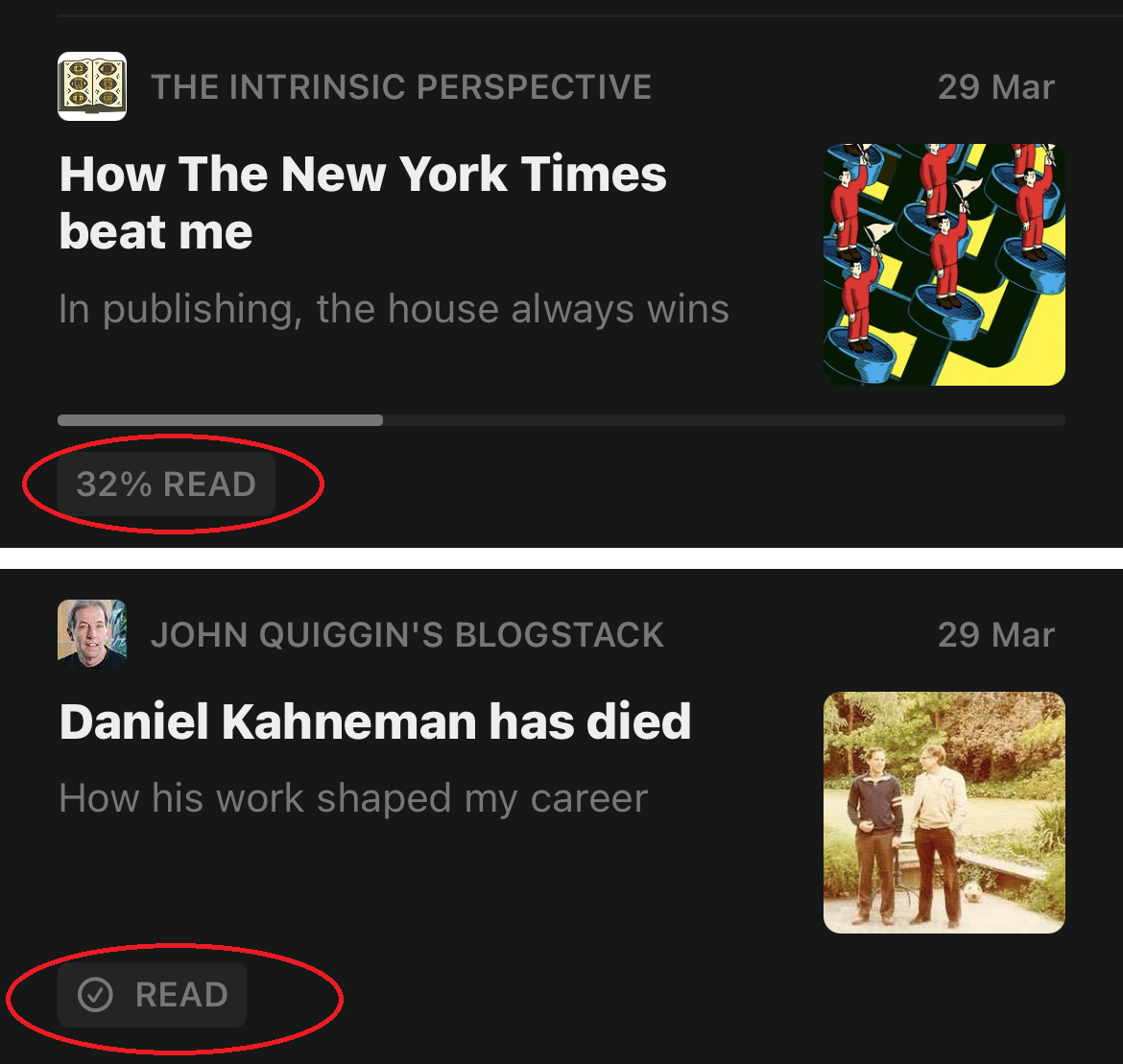

It would be very interesting for Substack writers to have the same information. They could for instance notice when people got bored and moved away from a post. Could Substack provide this information to writers? Yes, it could. When you are on Substack’s app, it tells you how much of a post you read, if you finished it or paused halfway through. Here is an example:

If Substack has this information it could give it to its contributors in the dashboard like Youtube. But it does not or at least not prominently and clearly. The dashboard contains an “engagement” metric. Here is the example given by Substack’s explanation of how it works. In this example, the post received an engagement of 2%. What does it mean? When hovering over the question mark, we can read (emphasis mine).

The percentage of subscribers who engaged with this post after opening an email or mobile app notification for the post. Engagements include: liking a post, clicking a link, sharing or restacking a post, commenting on a post, and reading a post to the bottom.

So this metric gives an upper bound of the percentage of subscribers who finished the post after opening it…. And Substack’s example gives a 2% engagement rate! It suggests that for 1,000 "views” from subscribers only 20 would read till the end. I suspect this number may give a pessimistic picture. In some cases, people may finish a post without scrolling to its bottom, because the poster has put extra material at the end (e.g., this post has references and footnotes). Nonetheless, it suggests the effective attention a post receives may be much less than the number of “views” indicated by Substack.5

Why doesn’t Substack provide the same information as YouTube? I think the likely reason is a question of incentives. YouTube’s business model is based on advertising during videos. YouTube therefore has an interest in making producers aware of how their videos are doing throughout to induce them to produce engaging content that keeps people watching. In the tweet below, the user PaddyG96 does exactly this: using YouTube’s feedback as information and striving to reach a high retention.

Substack is not paid through advertising slotted in the posts. If it was, it might follow YouTube’s example and provide more feedback about audience retention. Compared to YouTube, Substack’s model is likely more based on motivating potential writers to join the platform than on motivating writers to make the most engaging posts.6

In disclosure games, glossy but imperfect information has to be interpreted as only showing a specific aspect of reality that is convenient to the sender of information. Given the incentives of social media platforms to keep us engaged, the lack of details on the engagement of the audience of our posts should be taken as an indication that it is likely not as impressive as the number of “views” we see. In such a case, no news is bad news.7

This post is part of a series on communication games. The next post will be on how cooperation is deeply woven into the fabric of communication exchanges with a discussion on pragmatics. As you have been so kind to reach the end of this post, please scroll to the end of the page for me to see how it affects the engagement metric!

References

Brown, A.L., Camerer, C.F. and Lovallo, D., 2012. To review or not to review? Limited strategic thinking at the movie box office. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 4(2), pp.1-26.

Grossman, S.J. and Hart, O.D., 1980. Disclosure laws and takeover bids. The Journal of Finance, 35(2), pp.323-334.

La Fontaine, J., 1668. Fables choisies, mises en vers par M. de La Fontaine

Jin, G.Z., Luca, M. and Martin, D., 2021. Is no news (perceived as) bad news? An experimental investigation of information disclosure. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 13(2), pp.141-173.

Milgrom, P., 2008. What the seller won't tell you: Persuasion and disclosure in markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), pp.115-131.

Milgrom, P. and Roberts, J. (1986) 'Relying on the Information of Interested Parties', Rand Journal of Economics, 17(1), pp. 18-32.

For the economic literature on this, see Grossman and Hart (1980) and Milgrom and Roberts (1986).

With Elon’s tweet, there are 405 thousand likes, 50.8 thousand retweets and, 24.2 comments for 55.9 million views. Across the different categories of interactions, there must be substantial overlap as many people who retweet also like (I typically do). Let’s assume there were 430 thousand unique users interacting, that would make 4.3 million readers.

Taking the mid-points of the intervals—0.5%, 2%, 7%, 15.5%—we can estimate the average in the sample as: 0.512*.5+0.277*2+0.134*7+0.076*15.5=2.93%.

The number of readers should be 33 times the number of likes (100 readers for 3 likes). This estimation is obviously tentative, but even if the proportion of likes for Elon’s tweet was only 1% his estimated number of readers would still be lower than the number of views (it would be 40.5 million). The proportion of likes likely changes as a function of the tweet. The attentive reader will have noticed that my poll tweet only got three likes for 328 votes. Since all those who voted can be considered as having read the tweet, it means less than 1% of readers liked the tweet.

The numbers I have seen online suggest to me that engagement rates are often (perhaps most often) below 10%.

If you have enough new writers starting a Substack, some will happen to be very engaging and then you can promote them by algorithm. Instead of incentivising creators to be engaging, Substack’s incentives may be more geared toward incentivising potential creators to write.

The same insights would work in other areas:

This restaurant says it won the “Comparetto 2022 Prize of Excellence”, without further information. What is this prize? How many contestants? How many prizes could this restaurant have won but didn’t? And what was the ranking in the other competitions not mentioned?

This university says prominently on its website that it is #1 in the country (in small font: in graduates’ employability according to one survey). How many possible rankings could this university list but did not?

Wow this was very interesting! I don't know how it has zero comments but I can be among that percentage that does read the whole thing and does engage.

Don't worry: I read this post. All of it. It was good, too.