Glenn Loury's late admissions

Book review

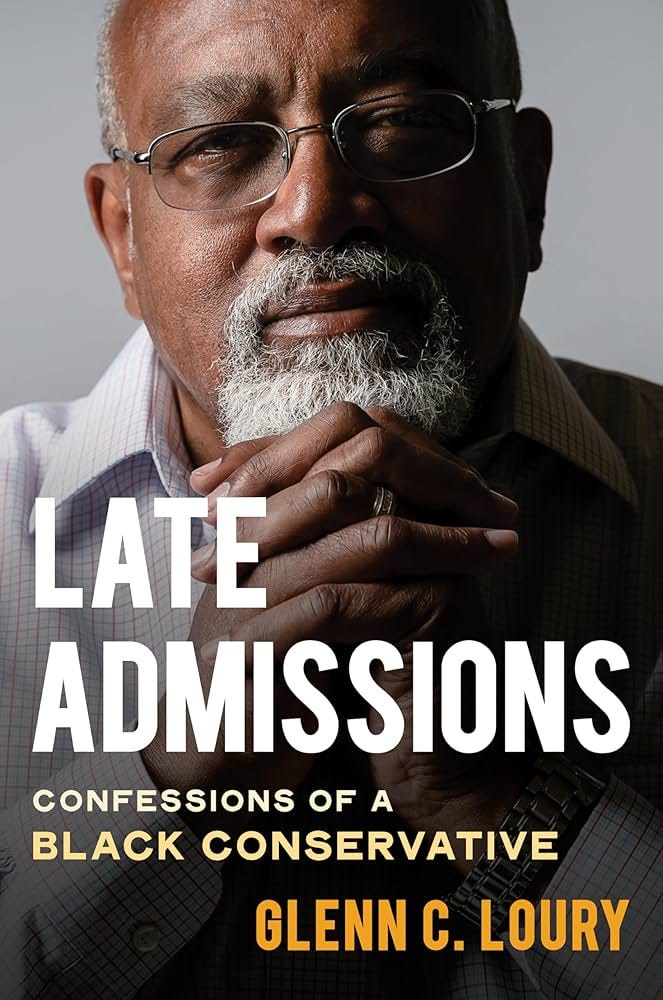

Late Admissions is a fascinating and gripping autobiography by Glenn Loury, an economist who became the first black economist tenured at Harvard at 33.1 Loury may nowadays be familiar to people online as the host of the Glenn Show where he discusses political issues, often with linguist John McWhorter, particularly focusing on racial politics in the US.

To many economists and intellectuals, Loury’s name carries a different significance. He is known for his critical contributions to the study of affirmative action, critiquing the unintended consequences of this well-meaning policy (Coate and Loury, 1993; Loury, 2002). He pointed out that by lowering admission standards for specific minorities, affirmative action can inadvertently reinforce negative stereotypes about them.2

I first encountered his work when, as a young researcher, I collaborated with Amine Ouazad on studying the possible perception of discrimination by minority students in the UK.3 Later, I came across his paper on self-censorship in public discourse (1994), one of the most insightful works I’ve read on the strategic aspects of communication, reminiscent of Thomas Schelling’s writings on game theory.

The life story: an incredible roller coaster

Loury’s book is gripping. From a hardworking lower-middle-class black background in Chicago, he rose to prominence in American academia. He then metaphorically and literally almost fell into the gutter before finding his footing again. It would make for a great Hollywood biopic.

The book begins with his youth in a black neighbourhood on the South side of Chicago. Loury recounts how his aunt would often warn him not to cross a metaphorical “line” that divides those who move upward and those who fall into destitution—a line he would come close to several times. As a young man, he was arrested for stealing a car to take his girlfriend to prom. Later, he dropped out of the Illinois Institute of Technology after missing too many classes and failing exams. By age 20, he was working in a printing plant and had two children from unplanned pregnancies with his then-partner.

But Loury’s story could just as well have been the inspiration for the movie Good Will Hunting. After enrolling in a local community college, a teacher recognised his talent and encouraged him to apply for a programme at Northwestern University for gifted inner-city students. Loury applied, was accepted, and thrived in this new environment, excelling beyond his peers.4

His life then followed two parallel tracks: a professional success story and an unbridled personal life. Professionally, Loury excelled: he earned a PhD from MIT, received job offers from top universities, and held positions at Michigan and Harvard. In that life, he was a brilliant and successful young economist, publishing influential theoretical papers in leading journals. On the personal side, however, the story was, to say the least, somewhat different. Loury candidly describes his unrestrained social and romantic life with many dalliances, one of them being a young mistress, with whom he lived a parallel life in an apartment he rented for her.

Like in a Greek tragedy, the rising star’s incredibly fast climb to the top foreshadowed a fall. This fall came in successive steps. First, the pressure of the expectations at Harvard (as felt by Loury himself) proved too high. Despite reassurance from his colleague Tom Schelling that everyone at Harvard experienced similar pressures, Loury “choked,” as he described it. He chose to shift away from abstract academic work in the economics department and moved to the Kennedy School, where his interest in political issues was appreciated. There, he gradually became a conservative political critic. This move away from the coalface of pure academic research seemed like a good one; soon, he was touted for a position as Under Secretary of Education in the Reagan administration.

But then it all came crashing down, and Loury has somehow prepared us for this as he describes the growing tension between his two lives. Falling to the hubris that so naturally comes with rapid social success, Loury blurred the lines between his personal and public life, inviting his mistress to conferences and public events, to the dismay of his colleagues. Reality came back fast when the FBI, likely running a background check on someone considered for a possible government position, uncovered the rented apartment for his mistress. Realising this made him, in all likelihood, unfit for a position in a conservative administration, Loury withdrew his name from the nomination process.

Shortly after he feuded with his mistress and physically moved her out of the flat. She accused him of physical violence during that incident and the case became public. It was his public reputation that was now tarnished (she later dropped the accusation of physical violence, which Loury firmly denied in the first place). Having flown so high, the fall was hard. First, he had moved away from the arena of abstract research where he initially aimed to excel. Now, the path of political influence that seemed open to him had suddenly closed. His role as a social critic had to be put on hold too. It is difficult to take the moral high ground in public discussions when it is common knowledge that one’s personal life is not in line with the moral principles professed.

Loury’s life then took a turn for the worse. Already used to recreational drugs like cannabis, he was introduced, in one of his adventures, to try something new which happened to be crack cocaine. Before he realised it, he became addicted, deeply addicted. While he tried to rationalise and deny his addiction, crack began to dissolve his life and motivation, taking hold of his drives and thoughts.

As Loury describes his progressive descent into hell, he recounts being mugged in sordid back alleys and getting high alone in his car, or in his office, hiding from colleagues. Eventually, his two lives collided again, and he was arrested with crack cocaine in his car. The case went public.

It took two intense stays in isolated rehab centres for Loury to gradually regain control of his life and resist the pull of the drug. From that point, he started to rebuild his career, moving to Boston University and re-establishing himself as both a successful academic and a social critic.

An insightful story on the human condition of intellectuals: high ideals and self-interests

While Glenn Loury’s life is striking in itself, the most fascinating part for me is his candour about his inner motives as a scientist and social critic.

The web of incentives of science

If you ask scientists how they chose their field of work they are likely to describe their curiosity in finding “the truth”, in “answering questions”, and in “changing the world”. Less frequently mentioned are motives like striving for social recognition and prestige. The pursuit of truth, even when it is part of a scientist’s motive, can also be a way to burnish your credibility as a producer of knowledge. The choice of research topics can be influenced by pragmatic considerations—what is likely to deliver results, gain recognition, and receive praise. Prestige and accolades are more likely if the topic fits the zeitgeist and allows one to display technical skills. Loury is not shy to say how he enjoyed the recognition and admiration of colleagues, saying aloud what scientists seldom admit so explicitly.

This backstage view of science is highly relevant to a key question about science: how does truth emerge? The answer is that it doesn’t simply stem from internal motives to discover the truth. Instead, it results from the effect of external incentives within the scientific process. Scientists’ standing depends on their reputation. Knowing that errors can damage their long-term reputation, they are cautious with their claims. Peer scrutiny and the public record of science promote then the success of rigorous, relevant ideas. These reputational incentives can be internalised into a personal ethos, making scientists mindful to stay rigorous and avoid endorsing bad ideas for short-term gains. In several places, Loury displays such an ethos as he expresses self-doubt: Am I asking the right questions? Are my answers—currently receiving praise—right? These inner doubts led him to revise his perspective, often against his political coalition at the time.

Politics

Another fascinating aspect is Loury’s navigation of both scientific and political arenas, each driven by different incentives. Politics, unlike science, is shaped more by coalitional dynamics than by epistemic rules. Loury, initially left-leaning, felt increasingly distant from what he calls the Black American “cognoscenti” elite, who he saw as disconnected from the lower social background of most blacks and as perpetuating outdated narratives from the civil rights movement. To him, their slogans failed to address what he saw as core issues like crime and family breakdown in black communities.

Loury shows rare clarity in recognising the conflicting motives underlying his political involvement and an even rarer willingness to share them. He recounts a moment in 1984 when he challenged the Black political elite in a meeting in Washington, declaring, “The Civil Rights Movement is over!” He takes pride in confronting them, likely aware that he is proving his intellectual worth by challenging their weak political narratives.

When he shifted toward conservative politics in the 1980s, his blackness provided what he calls “cover” to criticise left-wing views on race without risking accusations of racism.5 In that sense, he was useful to conservatives and Loury recognises that his race enhanced his value in coalitional politics, accelerating his rise. However, during the 1990s, Loury progressively left conservative politics and rejoined the liberal fold. The story of how this happened provides great insights into how idealism, coalitional feelings and individual incentives shape ideological positions. The reality is neither as idealistic as The West Wing nor as cynical as House of Cards.

A pivotal moment in his political evolution came when conservative discourse, perhaps emboldened by its growing political acceptance, began blaming black Americans in ways that did not seem interested in finding solutions to improve their situation. Loury describes how this evolution progressively alienated him from the conservatives. He felt a growing sense of unease with a political side that increasingly seemed to praise commentators who potentially harboured racial animus against blacks. This realisation led Loury to take a more public stance against what he saw as punitive conservative stances on black Americans. He began a research program into the US carceral system that resulted in his 2008 book, Race, Incarceration, and American Values which criticised the rates of incarceration of black Americans.6

Rejoining the liberal fold earned him invitations and accolades. After one talk criticising conservative views on race, a fellow economist welcomed him back with a loud, “Welcome home.” Yet, Loury’s intellectual integrity made it difficult for him to remain aligned with any specific political coalition, as these coalitions often pursue politically self-serving arguments rather than well-grounded ones. Eventually, Loury felt that some inconvenient truths were coming back, nagging him: While incarceration of black Americans is a significant problem, he had not been considering the other side of the ledger—, what about the magnitude and causes of crime in black communities? This eventually led him back toward conservative politics.

In 2016, Loury supported Trump. It may surprise many readers given his intellectual depth. His public justification was Trump’s appeal to the legitimate grievances of white working-class voters, but Loury admits that he also liked Trump’s aggressive stance against political elites. After the January 2021 insurrection, Loury regretted his support.

Loury’s gambit of honesty in his autobiography

A recurring theme in Loury’s book is his candid self-assessment of past missteps. While he doesn’t explicitly seek forgiveness it must be clear that he hopes for some understanding and redemption.

The reader may be puzzled by the whole enterprise: why write this book, and why so much honesty about repeated failings? I take it that the riddle’s solution is in plain sight in the book, the search for social recognition and approval. Loury’s bargain with his readers is clear: he offers honesty in exchange for understanding and, perhaps, appreciation.

Should readers take a dim view of this as a self-serving attempt at redemption? By his candour about the complex incentives behind idealistic standpoints, Loury may have, by the end of the book, disarmed such reactions. If you feel a drive to take a condemning moral standpoint, why is it so? Is there any chance your motives may not be purely idealistic but also influenced by the benefits of taking a moralistic stance signalling your own rectitude, or perhaps your coalitional preferences and loyalties?

As Loury concludes his book about an incredible life of high peaks and profound abysses, of high intellectual achievements and serious misgivings, I can imagine him staring his reader in the eyes hoping to be recognised for his achievements and, if not forgiven, understood for his failings as extreme as they may have been: “Dear readers, it is all true. I was human, too human. If ever you are tempted to judge me too harshly, perhaps consider whether you are as honest with your moral standpoint as I have been with mine in this book”.

References

Coate, S. and Loury, G.C., 1993. Will affirmative-action policies eliminate negative stereotypes?. The American Economic Review, pp.1220-1240.

Henderson, R. 2024. Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class. Gallery Books

Loury, G.C., 1994. Self-censorship in public discourse: A theory of “political correctness” and related phenomena. Rationality and Society, 6(4), pp.428-461.

Loury, G.C., 2002. The anatomy of racial inequality. Harvard University Press.

Loury, G.C., 2008. Race, incarceration, and American values. MIT Press.

Loury, G.C., 2024. Late Admissions. Norton agency titles.

Ouazad, A. and Page, L., 2013. Students' perceptions of teacher biases: Experimental economics in schools. Journal of Public Economics, 105, pp.116-130.

I will follow Glenn Loury’s preferred style of not capitalising the word “black”.

The argument is that if members of a disadvantaged group are selected/promoted on the basis of their group membership rather than on their qualifications/skills, it may reinforce the belief that they are less qualified/skilled for the position they occupy than other people.

Our work was commissioned by the British Department of Education. We found interesting results in our study (Ouazad and Page, 2013), though no indication that minority students felt discriminated against.

By some striking coincidence, Rob Henderson’s book Troubled published this year has a very similar arc. Rob is famous for developing the idea of “luxury beliefs” to describe somewhat artificial beliefs held in parts of the elite for social prestige. The idea is interesting, though the mechanisms behind luxury beliefs would have to differ from how luxury goods work. I’ll likely write a post about this at some point.

Loury discusses this in his 1994 paper:

standing to address an issue is restricted to a certain class of persons who have what I will call “natural cover.” These are people who, because of their group identity, are not immediately presumed to have malign motives for expressing themselves in a potentially offensive way.

Thus Blacks, but not Whites, can make movies or report news stories on the problem of skin color prejudice, which continues to affect African American society. […] The censorship in these cases is partial; those who have “cover” express themselves freely; those who lack it must be silent. - Loury (1994, emphasis in the original text)

This book includes a contribution from the French Boudieusian sociologist Loïc Wacquant with whom Glenn Loury has collaborated on this topic. I point this out as Bourdieu’s sociology is politically marked on the radical left side of the political discourse with its criticisms of social institutions and the social domination they perpetuate from some social groups on other groups.

Brilliant review. Sounds like a brilliant book too.