Dekanting moral philosophy

Unconditional moral duties do not follow from pure rationality

In this series of posts on how to understand morality, I argue that moral behaviour and moral beliefs are human solutions that help sustain mutually beneficial cooperation in society. From that perspective, game theory, especially as articulated in the work of Ken Binmore, can help clarify the seemingly mysterious questions about what morality is and how it works. To complete this journey, one cannot ignore one of the most influential moral philosophers, Immanuel Kant. He is more frequently cited than understood, partly because of his difficult writing style. Here, I want to present clearly the crux of Kant’s view of morality and why it is wrong. For anyone interested in morality who has found Kant daunting, this post should be of useful. I have tried to make the core of the argument as clear as possible.

Where does morality come from? Why should we be moral? These questions are, surprisingly, mysterious given that moral beliefs and practices are pervasive in our lives.

For centuries, a straightforward answer in countries with monotheistic religions was: “it comes from God’s will”. Sacred books gave (often very detailed) injunctions about what to believe and what to do in order to be a “good” person.

The European Enlightenment witnessed a secularisation of thought in science and philosophy. In that context, the Scottish philosopher David Hume proposed a radically different view (which I develop on this Substack): morality is only a human affair. Moral rules are social conventions that make human interaction and cooperation possible.1 There is no need to invoke anything “out there” to explain why we care about morality and why we (most often) follow moral rules.

The view of morality as arising from social conventions can feel underwhelming. One might think that something reassuringly “absolute” is lost. Isn’t there a “Right” and a “Good” that we are meant to follow because they are true independently of what we think?2

Contra Hume, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant defended an absolute view of morality within a secular theory. Kant is often described as the central figure of modern philosophy. In his History of Western Philosophy (1945), Bertrand Russell described Kant as:

[Being] generally considered the greatest of modern philosophers — Russell (1945)3

and The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy starts its article on Kant with the following description:

Immanuel Kant is the central figure in modern philosophy.

Kant’s philosophy concerns both what we can know about the world (Critique of Pure Reason) and what we should do with this knowledge (Critique of Practical Reason). In this second aspect of his work, Kant argued that the moral “ought” is unconditional and universal. Morality is not a matter of convention. It stems from human rationality.4

Kant’s project can be thought of as retaining the unconditional character of Christian moral prescriptions, without appealing to divine command. Once we abandon religion as a foundation of morality, Kant’s enterprise is one of the most influential attempts to recover an absolute view of morality. In his view, moral rules are necessary if we want to live as rational beings. Even if everybody disagreed with these rules, they would nonetheless be true.5

In spite of his fame, we can now say, with the benefit of two more centuries of work on rational decision-making, that Kant got it wrong. In his books on game theory and the social contract, Binmore offers a frank criticism of Kant, which I will broadly develop here.

[Kant] gets pretty much everything upside down and back to front. — Binmore (2005)

The categorical imperative

Kant aims to found morality on rationality. He explains his views in the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. The key idea he defends is that moral behaviour consists in following moral “oughts” that do not depend on incentives, enforcement, or local convention. These oughts stem from a single principle, the categorical imperative:6

Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.7

There have been many criticisms of the impracticality of Kant’s moral principle. One of them, raised during Kant’s lifetime by the French political thinker Benjamin Constant, is that if one follows Kant’s categorical imperative, one ought to tell the truth to a murderer who knocks at our door and asks whether his intended victim is in our house. Kant replied without denying this implication. He stated that lying in such a situation would “do wrong to men in general”.8 So when a Nazi officer asks you whether you are sheltering Jewish children, the moral thing to do, on this strict reading, is to tell the truth. If you lie, what next? Trust in each other’s words would crumble in society!

Here, I present a criticism that is more fundamental than these familiar objections. My claim is that Kant’s assertion that the categorical imperative follows directly from human rationality is misguided.

The contractual intuitions behind Kant’s morality

Before taking down Kant’s argument, it is worth appreciating its intellectual appeal. There is a contractualist intuition behind Kant’s morality. This intuition is not the one Kant uses as an explicit argument, but I think it is what made his view compelling.

Because we live in society, we need rules to organise social interactions. What rules defining duties and rights can we endorse? If these rules have to be accepted by all, and if we have similar bargaining power, a simple logic emerges: we cannot defend rules that give rights to ourselves and impose duties on others in a way that does not apply symmetrically. Hence, in a society of equal members, the only rules of behaviour that we can claim to be allowed to follow are those that we must accept could be followed by others.9

This contractualist intuition makes Kant’s argument appealing, but it is important to distinguish two different questions:

The social question (a social contract):

How should we all agree on shared social rules—a “social contract”—in a given community?

The contractarian position I defend in this series is that morality exists to sustain such a social contract. That is why we intuitively feel that we cannot claim a right to do things to others that we would not accept them doing to us.

The individual question (a rule for personal conduct):

How should you behave as an individual?

This is an individual choice you make for yourself, not a collective choice you make with others.

The intuitive appeal of Kant’s answer comes, I think, from implicitly channelling our contractual intuitions about the social question into the individual question. But Kant is not searching for social rules to adopt as a group. He is looking for a principle of behaviour that each person should adopt independently. Kant’s answer is misguided because the contractarian answer to the social question is not an answer to the individual question.

The flaw in the argument

In Natural Justice, Binmore makes this point, which is ironic but goes to the crux of the flaw in Kant’s argument:

Kant claimed that a truly rational individual will necessarily observe one particular categorical imperative: “Act only on the maxim that you would at the same time will to be a universal law.” My mother had similar views. When I was naughty, she would say, “Suppose everybody behaved like that?” Even to a child, the flaws in this line of reasoning are obvious. It is true that things would be unpleasant if everybody were naughty, but I’m not everybody—I’m just myself. — Binmore (2005)

The key point is that Kant tells us it is rational to follow a rule that would work well if everybody else were following it. But our adoption of that rule is a decision we make on our own, with no effect on other people’s decisions. What if others do not follow suit? Is it still rational?

Starting with a well-known example: the Prisoner’s Dilemma

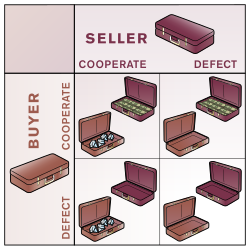

At this point, we benefit from the clarity that game theory brings to thinking about rational decisions in social interactions. The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a particularly useful case for testing Kant’s conclusion. The dilemma involves two people who can either cooperate with each other or not.10

I will use a version of the dilemma that is, deliberately, stripped of moral sentiment between the players.11 Consider two gangsters who plan to exchange diamonds for cash. They can only meet briefly in a train station. Because the place is public and the meeting must be quick, they can only swap briefcases and leave, without checking what is inside. Each gangster faces a choice: he can honour the deal (cooperate) and bring the promised item, or he can bring an empty briefcase (defect) in the hope of getting the other briefcase for free.

Assume the two gangsters do not know each other and will travel to different countries immediately after the exchange, never to meet again. Their decision has no future consequences for them. What should they do?

Because they have no personal connection, they do not care about each other’s wellbeing. In that case, it quickly becomes clear that the individually rational choice for each is to defect. Consider the buyer. Two states of the world are possible: either the seller brings the diamonds, or he does not. In either case, the buyer is better off giving nothing, whether he receives diamonds or nothing. The seller faces the same logic: he is better off bringing nothing.

The dilemma is that if both follow their individual rationality, the exchange fails, even though both would prefer the outcome where the cash and the diamonds are successfully traded. A tremendous amount has been written on this problem. Because the conclusion is uncomfortable, many authors have tried to argue that it would somehow be “rational” to cooperate. We need to put this idea to rest: it is an intellectual dead end. If we assume that the players do not care for each other and will not interact in the future, the only rational strategy (the best strategy for them to get what they care about) is to defect.12

Kant’s categorical imperative conflicts with this conclusion. It suggests that cooperation is the rational choice because it is the kind of action one could accept as a rule for everyone. If both cooperated, the exchange would take place; if both defected, it would not.

But the structure of the Prisoner’s Dilemma shows why this is not a usable principle for individual action. The problem is that choosing a maxim because it would be good if it were universal does not make it universal.13 In the gangster exchange, the only thing each person can choose is his own action. There is no point saying “this would be a great action if everybody chose it” if the other person has no reason to choose it.

Choosing to follow the categorical imperative would lead to a better world only if my choice could somehow influence others’ choices. But that is not the case. In the example above, one gangster’s decision to cooperate does not produce some “spooky action at a distance” that makes the other gangster cooperate as well.14

Criticising the core of Kant’s argument about the categorical imperative

Let us now turn to Kant’s argument that the categorical imperative stems from the requirements of human rationality.

[T]he will of every rational being is necessarily bound to it as a constraint. — Kant

Binmore takes this argument seriously. What should a maxim of behaviour chosen by a rational being be? The notion of rationality is not simple,15 but we can start from a minimal idea: behaviour is rational if it can be rationalised, in the sense that one can give reasons for it.16

A formal insight from economics is that rationality can be characterised, to some extent, by consistency. If a person’s choices satisfy certain basic consistency requirements, those choices can be described as if the person had a stable objective.17

Binmore begins from this point and asks whether Kant’s categorical imperative follows naturally from the search for consistent principles of behaviour. A first (small) problem is that Kant’s test is applied maxim by maxim. That leaves room for overly specific maxims. For instance, regarding the challenge of whether you should tell the truth to a Nazi looking for Jewish people hiding in your house, one could adopt the maxim:

Never tell a Nazi who is looking for innocent victims where to find them.

That is, of course, a defensible maxim. But it illustrates the problem: once we allow very narrow conditions, it becomes easy to tailor a maxim to reach the conclusion we want. If the conditions are specific enough, the “universality” of its content can become almost empty, because it may in practice apply only to one person.18 The question then becomes: why these conditions, and why this maxim rather than another? In practice, it looks as though we need further principles to justify the way we chose to describe the maxim in the first place, for example a principle about protecting innocent people.

For this reason, Binmore does not consider maxims individually, but as a whole. If we consider the full set of principles that would be implied by the categorical imperative, we end up with a system of rules (maxims) guiding action.

So consider an individual choosing a set of rules to follow. A simple requirement of consistency is that the set of rules should not undermine itself: following those rules should be compatible with continuing to follow them. Put differently, a coherent system of rules should be self-justifying. If you apply your own rules to the question “which rules should I adopt?”, they should not force you to abandon themselves. Binmore expresses this idea as a rational imperative to choose for yourself a bundle of maxims (my phrasing for simplicity).

Choose rules for yourself that you can stick with when you reflect on your own rule-choosing.

If one associates rationality with avoiding inconsistency in the principles guiding behaviour, this requirement is not controversial. It may sound abstract, so an example helps. Suppose your overarching rule is:

In every situation, choose the option that best advances your aims, given what you believe about the situation.

That rule is compatible with continuing to follow it. By contrast, consider an overarching rule such as:

Always do the opposite of what this system recommends.

That system cannot be self-justifying. If you try to follow it, it tells you not to follow it.

Now we can ask a similar question at the social level: what rules could everyone adopt together, and still have reason to keep following? An answer would be:

Choose rules for society that people can keep sticking with once everyone has adopted them.

In other words, if we had to choose as a society, we should prefer rules that are self-sustaining, in the sense that if everyone adopts them, each person still has reason to keep following them rather than immediately wanting to switch.19

This addresses the social question: what rules can serve as a stable social contract? But Kant is not trying to answer that question. He is trying to answer the individual question: what rules should each person adopt for themselves?

Kant’s prescription is that you, as an individual, should choose rules for yourself that you would accept everyone using. Binmore rephrases Kant’s categorical imperative as:

Act on the basis of a system of maxims that you would at the same time will to be universal law. (I emphasised the addition of “a system of”)

We can rephrase this, for simplicity, as:

Choose rules for yourself that you could at the same time will everyone to use.

The problem is what “will” means here. You may want others to follow your principles, but your choice of principles has no causal effect on what they choose. You can decide that a rule would be appropriate for everyone, but that decision does not make anyone else follow it. You cannot “will” other people into compliance just by endorsing a rule.

In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the buyer might decide to cooperate because the exchange succeeds if everybody cooperates. But the buyer’s choice of maxim has no effect on the seller’s choice of maxim.20 As Binmore puts it:

[I]t is impossible for an individual to make what Kant calls a “natural law” that everybody should behave as though they were clones. Indeed, it seems to me quite bizarre that a call to behave as though something impossible were possible should be represented as an instruction to behave rationally. Far from expressing a “rational preference”, the “will” of Kant’s categorical imperative seems to me to represent nothing more than a straightforward piece of wishful thinking.

Binmore’s complaint is that Kant’s test tempts us to choose the “best” action by imagining an ideal world in which everyone complies. To caricature, one might summarise the categorical imperative as:

Choose to behave in a way that would be great if everybody else were doing it.

But if you are looking for a rational answer to the individual question, you should instead look for the best action for the individual, given what others are actually doing. If others are like you, they will also try to choose what is best for them given what everyone else is doing. In other words, looking for a consistent rule of behaviour from the individual point of view leads to a different kind of categorical imperative, one in which people aim to make decisions consistent with their preferences, assuming others are also doing the same. Binmore proposes something like (my phrasing):

Choose to behave in a way that is best for you, given everyone else’s choices, assuming that others are also choosing what is best for them, given everyone else’s choices.21

An individually rational rule of choice that could be adopted by all is one in which everyone chooses what is best for them (given their preferences), assuming that all other people are also trying to do the same.

So this maxim tells you that it is rational to behave in a way that assumes realistic behaviour from other people (and not idealised behaviour), with each person also having realistic assumptions about the behaviour of others. A situation where everybody mutually best responds to other people’s behaviour is a Nash equilibrium. For that reason, Binmore calls this second imperative the “Nash categorical imperative”.

Binmore is not presenting this as a moral principle. He is presenting it as a requirement of rational choice in strategic settings. It does not ask you to assume that others will behave more cooperatively than their incentives allow. A “rational” rule of choice, in this sense, is one that can be used by everyone at once, with each person still having reason to stick with it given that everyone else is doing the same.

Rationality is playing the best response against actual behaviour

The categorical imperative recommends behaving in the best possible way IF everybody were willing to behave that way.22 But in reality, people may have good reasons not to. If so, what happens if you follow the categorical imperative and end up being the only one who does? In many settings, doing the “right” thing in that sense can lead to worse outcomes when others do not follow you. Here are two illustrations.

Illustration 1: a mutual deterrence standoff

A specific type of equilibrium occurs when two opponents are locked into a mutual deterrence situation. In gangster and Western movies, it takes the form of a “Mexican standoff” with opponents aiming guns at each other. In international relations, nuclear deterrence between powers capable of devastating retaliation has the same structure.

It is easy to represent such situations with the logic of a Prisoner’s Dilemma: both sides would be better off if neither threatened the other, but whatever one side does, the other has incentives to keep its guard up, either for protection or to gain advantage if the other side lowers its guard.

Kant’s categorical imperative would suggest adopting the behaviour we would like everyone to adopt. Since mutual peace is the best outcome, I should “rationally” lower my guard.23

Any experienced movie watcher will tell you that lowering your guard in a Mexican standoff is usually a terrible idea. It does not cause the other person to lower his guard. It leads you to be his prisoner or to end up dead. In international relations, few people find the suggestion that the United States should have unilaterally disarmed during the Cold War plausible. Indeed, Ukraine’s abandonment of nuclear weapons on its territory in 1994 did not lead others to do so, but instead allowed Russia to invade it a few decades later in a war that led to hundreds of thousands of deaths.

Illustration 2: the Nader-Gore choice in 2000

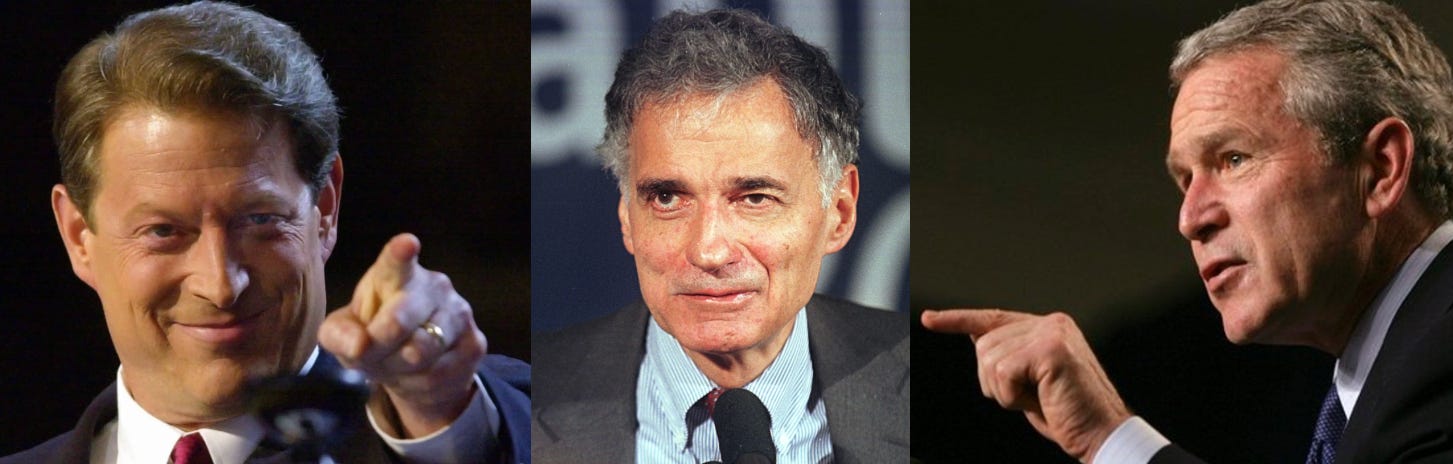

Suppose you are a progressive-minded voter in the United States in the year 2000. You can choose between two candidates: the Green Party’s Ralph Nader and the Democrat Al Gore. Suppose you believe Nader has the best policies. The categorical imperative tells you that you should vote for him because, if everybody voted for him, the United States would be a better place.

The difficulty is that Nader, at around 3% in the polls, had little chance of winning. Gore, on the other hand, was in a very close race with George W. Bush. In that setting, voting “on principle” for Nader might not affect Nader’s prospects, but it could contribute to Bush defeating Gore.

In the end, this is roughly what happened. The result was decided in Florida, where Bush won by only 537 votes, while 97,488 votes were cast for Nader in that state. This is one of many examples where people doing “the right thing” while ignoring what others plan to do end up with worse consequences all around (from the perspective of the people making the decision).24

Here is how some Nader voters later described their choice:

At the time, I thought I was making a principled stand, but it’s a vote I have come to regret. — Josh Brodesky25

Then that night I really regretted it. I was in Pennsylvania too, so it’s like a consequential vote. — A radio talk show caller26

Smoking is not the worst choice I made that year. I voted for Ralph Nader. — Rachel Combe27

Kant’s argument that it is individually rational to behave in this way does not hold up. The categorical imperative has intellectual appeal, largely because it resonates with our contractarian intuitions about what rules could be shared. But those intuitions are not answering Kant’s question. Kant is not asking how we should choose rules together, but what each person should adopt for themselves. By asking us to behave best not in the world as it is but in the world as it should be, Kant’s categorical imperative risks asking us to behave in an irresponsible and deluded manner.

Modern thinking about rationality, as developed by game theorists, allows us to scrutinise Kant’s claim more sharply. His idea that the categorical imperative follows from rationality does not survive that scrutiny. On this point, Binmore concludes that once one gets past the difficulty of reading Kant:

Kant’s assertion that one should honor this principle for rational reasons is conjured from the air. — Binmore (2005)

No unconditional oughts

Kant’s biggest claim in moral philosophy is that sheer rationality generates an unconditional ought: I ought to follow the categorical imperative simply because I am a rational being.

The idea of an unconditional ought may feel especially attractive in societies shaped by Judeo-Christian heritage, where moral rules were long presented as commands imposed from above by a divine being. Without the appeal to such a being, many philosophers, including Kant, tried to retain the idea of unconditional obligation. But we have seen that Kant’s attempt fails: his categorical imperative does not follow from rationality.

Modern theories of rational choice provide a clearer foundation for what “ought” can mean. Rationality is always about doing the right thing to achieve what one wants to achieve (whatever it is). In that sense, we can talk about “oughts”, but only as conditional oughts: IF I want to achieve my goal A, THEN I ought to take action B.

When people interact, these conditional “oughts” must incorporate what others are likely to do. Any stable pattern of social interaction between rational agents will take the form of a Nash equilibrium: people persist in their behaviour because it is best for them given what others are doing, and this must be true for everyone.

In line with the Humean tradition, morality can be understood as a set of cultural conventions that regulate social interactions. Their features have been selected over time because they help realise gains from cooperation. These conventions are equilibria and therefore self-enforcing. In a society with functional moral rules, it is often in each person’s interest to follow them in order to avoid social sanctions. Hence, there is a conditional ought: IF one wants to remain an accepted member of society, THEN one must abide by the moral rules of that society.

This answer is often described as underwhelming, but that is partly because it is an ultimate explanation: it explains what morality is at a fundamental level. It does not necessarily match our moral experience. To understand how morality feels from the inside, we need a proximate explanation: an account of the emotions and intuitions that guide us. We have evolved a moral sense that helps us navigate social life. In the same way that fear or hunger pushes behaviour in directions conducive to survival, social emotions such as guilt and empathy help us manage cooperation, conflict, and reputation. As a result, we do not experience moral decisions as interest-driven. We often experience them as the requirement to do what is right, and the fear of doing wrong when we violate a rule. Paradoxically, those proximate feelings may also make the ultimate explanation of morality feel disappointing. But our intuitions should not determine what we accept as the best theory.

I have the intuition that the world is solid and well-defined. I also find the picture of nature provided by quantum theory unintuitive and unappealing. But IF I want to navigate the world successfully, THEN I ought to accept the best theory available. From that perspective, the contractarian theory of morality, particularly as articulated by Ken Binmore, is the best available in its ability to account for what morality is, how it works, and how it evolves.28

Kant’s figure looms large in Western philosophy. His attempt to found morality in sheer rationality seems deep and impressive. But discussions of rationality are complex and easily confused. With two centuries of work in decision theory and game theory behind us, we can move beyond Kant’s daunting prose and identify what is wrong with his argument. The categorical imperative encourages us to behave best in the world as it should be, not in the world as it is. In many situations, that is not a sensible guide to individual choice. It can lead us to act in ways that fail to achieve what we want, and sometimes in ways that worsen outcomes for others. It is not clear in what sense this is either rational or moral.

One way to place Kant’s morality in the history of ideas is as a rearguard attempt to retain, in secular form, the absolutist flavour of Judeo-Christian moral obligation. The view I defend in this series is that Hume’s alternative was fundamentally right: morality can be understood as emerging from a social contract, an implicit agreement about how to behave properly in society. Game theory helps us understand the logic underlying social interaction and, in doing so, helps us develop a theory of morality that fits our practices and beliefs. Unlike Kant’s views, this theory is stripped of mysterious content and does not require us to assume the existence of absolute moral principles of some kind that we would have to discover.

Having located this approach within the big questions of moral philosophy, I will develop it in detail in the next few posts.

References

Binmore, K. (1994) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 1: Playing Fair. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Binmore, K. (1998) Game Theory and the Social Contract, Volume 2: Just Playing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Binmore, K. (2005) Natural Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gilboa, I. (2009) Theory of Decision under Uncertainty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guyer, P. (2017) ‘Kant’, in Zalta, E.N. (ed.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 Edition). Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab.

Hume, D. ([1751] 1998) An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kant, I. (1797) ‘On a supposed right to tell lies from benevolent motives’.

Kant, I. ([1785] 2017) Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Translated by J. Bennett. Early Modern Texts.

Page, L. (2022) Optimally Irrational. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Quattrone, G.A. and Tversky, A. (1984) ‘Causal versus diagnostic contingencies: On self-deception and on the voter’s illusion’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(2), pp. 237–248.

Riker, W.H. (1962) The Theory of Political Coalitions. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Russell, B. (1945) A History of Western Philosophy. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Weber, M. ([1919] 1948) ‘Politics as a vocation’, in Gerth, H.H. and Mills, C.W. (eds) From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 77–128.

Similar ideas can be traced to ancient authors such as Aristotle, Epicurus, and Confucius.

In previous posts, I have criticised the idea that there are absolute moral truths.

Kant is, in a sense, returning to ideas already present in antiquity. For many major ancient philosophers, such as Plato, a virtuous life was the life in which a human being’s rational capacities functioned well. Vice and wrongdoing were seen as forms of ignorance, confusion, or irrationality. To live morally was to live rationally.

Russell immediately notes that he does not agree with this characterisation.

In the same way that ignoring mathematics does not make it false, disagreement about moral rules would not, on Kant’s view, make them untrue.

“Categorical” means “unconditional” here. Kant contrasts a categorical imperative with “hypothetical imperatives” of the form: “If you want X, you should do Y.” A categorical imperative does not depend on any further goal. It simply says: “You should do Y, not to get something else, but for the sake of doing the right thing.”

Kant also provides another formulation:

Act in such a way as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of anyone else, always as an end and never merely as a means.

Kant (1797).

This sentence expresses an intuition. A careful reader could ask in what sense one can only endorse symmetric rules between identical players. Indeed, game theory does not rule out asymmetric equilibria between identical players. Still, our intuition may reflect the fact that social coalitions are very flexible and that the only stable social arrangements are those that are symmetric as they do not invite the challenge of those who are disadvantaged.

For example, suppose Alice, Bob, and Candice must split a cake. Alice and Bob agree to split it 50–50 and give Candice nothing. If Candice has equal bargaining power as others and is able to form agreements, she might offer Alice a new deal: “Why don’t you take 60 and I take 40?” Bob is then excluded, but he can counter by offering Candice 50–50, excluding Alice. As the political scientist William Riker suggested, coalition instability may be one reason democracies tend to protect equal rights rather than stabilising into dictatorship.

Because this dilemma is so central, it was the topic of my first post on Substack.

We want to discuss whether rationality can ground moral behaviour by itself. So we need to start with rational agents who do not already have “moral preferences” or moral feelings. Otherwise we are explaining morality by assuming some version of morality in the agent’s motivations.

The standard “prisoner” framing involves two prisoners who must decide whether to inform on the other about a joint crime (defect) or stay silent (cooperate). Their choices determine their prison sentences. Both would prefer mutual silence, but individual incentives push them towards informing.

This framing is not always helpful because it can trigger moral intuitions. Since the prisoners are assumed to know each other and might see each other again, we may instinctively think they care about each other’s wellbeing, which makes cooperation feel natural.

The simple reply is that the Prisoner’s Dilemma should be understood with general payoffs. “Years in prison” is only an exposition device. If the players care about each other, that should be reflected in the payoffs. I prefer my gangster version precisely because it reduces the role of potential sympathetic feelings between the players.

As I wrote in a previous post:

Proposed political solutions that assume everyone will simply “do the right thing” are a red herring. A central challenge in political theory is that people typically do not all just want to do what might be in the best from a collective point of view.

There is a tension here. Mutual cooperation would be better for both players. But in my example the players cannot communicate, and each still has an incentive to defect. A player may choose against his own interests because the world would be better if everyone did so, but that choice does not, by itself, create the world in which everyone does so.

I discuss this concept within economics and game theory at length in Chapter 15 of Optimally Irrational (2022).

This definition matches the etymology of “rational”, from the Latin ratio (“reason”). In that sense, behaviour is rational if you can give reasons for it. It is also close to decision theorist Itzhak Gilboa’s view, where behaviour is rational if a person is prepared to stand by it when asked to explain why and how he or she acted.

For the economist readers, I am here referring to the foundations of consumer and utility theory whereby the adherence to a set of “axioms” imposing consistency constraints on choice is equivalent to the decision maker behaving as if he or she is maximising a well-defined utility function [references]. This utility function can be seen as the “goal” of the agent. It can be anything: getting the most money as possible, becoming famous, or reaching a higher level of spiritual awareness. The consistency of the behaviour is however required for it to be compatible with such a goal driven nature. A behaviour that would violate these rules would not be rationalisable in that the decision maker would not be able to answer something like “I did A because I wanted B”.

Naturally, Kantian philosophers are entitled to reject this thin, decision-theoretic notion of rationality and to claim that Kant’s theory relies on a different understanding. However, they should be wary of this move. There are not many clear, competing notions of “rationality” on offer. The definition used in economics has emerged from a long conceptual minefield as a minimal working notion for analysing behaviour. Kantians may not like it, but it is not as if there were already a well-articulated alternative they can simply invoke to support Kant’s claim. So rejecting the definition I use is fine in principle, but anyone who does so has the non-trivial task of offering a compelling alternative notion of rationality and showing how, on that notion, the categorical imperative really does follow.

Suppose Alice, who is 37 and lives in London, adopts this maxim:

Any woman called Alice and being 37 year old, living in London in 2026 should say thank you to the barrista on Clapham High Street when she gets her coffee on Monday morning.

The conditions attached to this maxim make the universalisation test almost empty. The maxim can be “universal” in a trivial sense, but it applies to virtually nobody other than Alice. This shows how easy it is to tailor a maxim so that it passes the test while doing no real moral work.

The attentive reader will notice that the meaning of “consistency” differs in the individual and the social case. The first is internal: a person’s set of rules should hang together and not undermine itself when the person reflects on what rules to adopt. The second is interpersonal: a rule is consistent at the social level only if it can be adopted by everyone at once without immediately giving some people reason to drop it once others adopt it too. In other words, the first concerns coherence within a single decision-maker; the second concerns stability across multiple decision-makers whose choices interact.

In their study of the psychology of voting, psychologists Quattrone and Tversky argued that people can behave as if their decision to vote were diagnostic of others’ decisions to vote, even though it has no causal effect on them. By deciding to vote, it can feel as if we are moving into a world where other people will also vote. A similar intuition can shape how we think about the Prisoner’s Dilemma: if we decide to cooperate, we may reason as if we are more likely to be in a world where the other person cooperates too.

To be clear, “best for you” and “best for them” means “best relative to the person’s preferences”. It does not imply that people must be selfish. If someone wants to be altruistic, he or she should choose the best actions to achieve that goal given what others are likely to do.

To the philosopher readers: A Kant specialist would likely say this is not how the categorical imperative is justified. Kant’s universalisation test is not a welfare test; it is about lawlikeness/contradiction (plus the “contradiction in the will” structure).

Kant specialists may object that “will” here means endorsing a maxim as a universal law, not desiring that others comply. Fair enough. My point is that, even on this reading, the categorical imperative is presented as a rule for individual action that abstracts from strategic dependence on others’ behaviour, which is precisely what game theory forces us to confront.

The sociologist Max Weber drew a famous contrast between an ethic of conviction (Gesinnungsethik), in which one acts from inner principles and lets the consequences fall where they may, and an ethic of responsibility (Verantwortungsethik), in which one takes ownership of the foreseeable results of one’s actions. His worry, especially in politics, was that a pure ethic of conviction can lead actors to ignore predictable harms and then absolve themselves of blame. Weber’s conclusion was that responsible political action must combine deep convictions with a clear-minded concern for consequences.

The case of Nader in 2000 is striking because Green voters were strongly anti-war, and many commentators argue that the election of Gore would likely not have led to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which was associated with very large loss of life. Questioning the rationality of the “principled” vote for Nader is therefore reasonable given the preferences of Green voters.

Similar cases can be found in many other countries. A notable example is the 2002 French presidential election. Around 10% of voters supported three small far-left anti-capitalist parties; their votes were not available to the mainstream social-democratic candidate, Lionel Jospin. He missed out on qualification for the run-off by 0.68 percentage points. The run-off then featured a conservative candidate (Chirac) and, for the first time, a far-right candidate (Le Pen).

https://www.mysanantonio.com/opinion/columnists/josh_brodesky/article/Confessions-of-a-Ralph-Nader-voter-7986369.php

https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/bl/segments/your-first-presidential-election

https://www.elle.com/culture/career-politics/a40020/dont-protest-vote

I’ll discuss these points in more detail in later posts.

Yes I like morality as good cooperation definitely much more than as following strange unbalanced imperatives which harm the morally acting individual!

I have a fundamental problem with basing moral principles on the notion that they should be universal imperatives because so many problems we have are a matter of scalability. If you have a handful of people with a problem that you can fix with money, paying out the money is often your best choice. But now you have created an incentive for more people to behave in ways that produce the problem. If people respond to the incentive, then at some point you will have to say "enough is enough". That doesn't mean that your initial payout was a bad idea. Or that stopping it was when you did. Being flexible is necessary for being moral, but that doesn't seem to fit very well with moral absolute oughts.