Cooperation is the scaffolding principle of life

From cells to humans, cooperation is a central principle of evolution

In one of his private letters, Engels stated the following about Darwin’s theory of evolution:

The whole Darwinists teaching of the struggle for existence is simply a transference from society to living nature of Hobbes’s doctrine of bellum omnium contra omnes [war of all against all].1 — Engels (1875)

The image of a war of all against all is a recurring framing of evolution. Thomas Henry Huxley, who became known as “Darwin’s Bulldog” for his staunch defence of Darwin’s theory, accepts this description and invites us to act against it by being ethical:

As I have already urged, the practice of that which is ethically best–what we call goodness or virtue–involves a course of conduct which, in all respects, is opposed to that which leads to success in the cosmic struggle for existence. In place of ruthless self-assertion it demands self-restraint; in place of thrusting aside, or treading down, all competitors, it requires that the individual shall not merely respect, but shall help his fellows; its influence is directed, not so much to the survival of the fittest, as to the fitting of as many as possible to survive. It repudiates the gladiatorial theory of existence. — Huxley (1893)

This view has often made it into social and political discussions, where evolutionary theory, and in particular its application to the study of human behaviour, is taken to imply a bleak vision of humans as being irremediably selfish. In his text The Western Illusion of Human Nature, the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins argues that evolutionary psychology has reinforced a Western trope of antisocial human nature:

The complementary idea that self-love is only natural has been reinforced lately by a wave of genetic determinism featuring the "selfish gene" of the sociobiologists and the revived Social Darwinism of the evolutionary psychologists. — Sahlins (2008)

This view is paradoxical. Anybody thinking that the core message of evolutionary theory is that we live in a war of all against all should stop and look around. Everything about life, as we can observe it, is produced by cooperation. Cooperation is not in conflict with evolution, it is generated by it.

Cooperation is everywhere in nature

The evolutionary psychologist Nichola Raihani wrote a book, The Social Instinct, on the importance of cooperation in the natural world. In an interview about it, she stated:

The history of life on Earth is a history of teamwork, collective action, and cooperation. Cooperation pays because being part of a team is better than going it alone. — Raihani (2021)

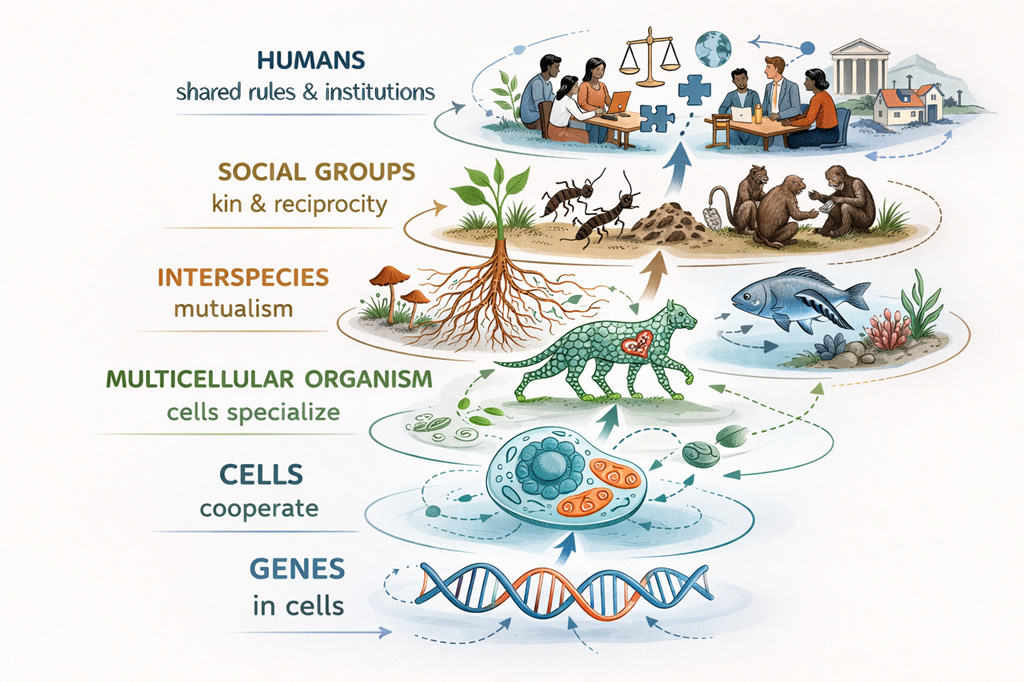

The parliament of genes

Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene made the point that genes are the units upon which evolution works. They are the replicators, which replicate and mutate. But in their drive for replication, genes “discovered” that they are stronger together. Instead of remaining isolated replicating molecules, they gathered in large “vehicles”, the cells and organisms, in which they share a fate and increase their chance of replication.

We are survival machines—robot vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes. — Dawkins (1976)

How cooperation is sustained. Within a cell or a multicellular organism, genes share a common “interest”. Their replication depends on the organism surviving, developing properly, and reproducing. Because genes that only “care” about their own replication tend to be selected, there is always the risk of mutations that increase their own transmission, potentially at the expense of the organism.

A standard example is meiotic drive (segregation distortion): during meiosis, a gene can sometimes bias transmission so it is inherited by more than 50% of offspring, even if this slightly reduces fertility or harms the organism. In short, genes can face prisoner’s dilemma-type tensions: cooperation is best for all, but cheating can be best for one, which makes cooperation fragile.

As a consequence, the cellular architectures that have emerged from evolution include mechanisms that detect and eliminate cheating. Distorters are countered by suppressors. This kind of internal governance has been described as a “parliament of genes” by evolutionary biologist Egbert Leigh in his 1971 book Adaptation and Diversity: Natural History and the Mathematics of Evolution.

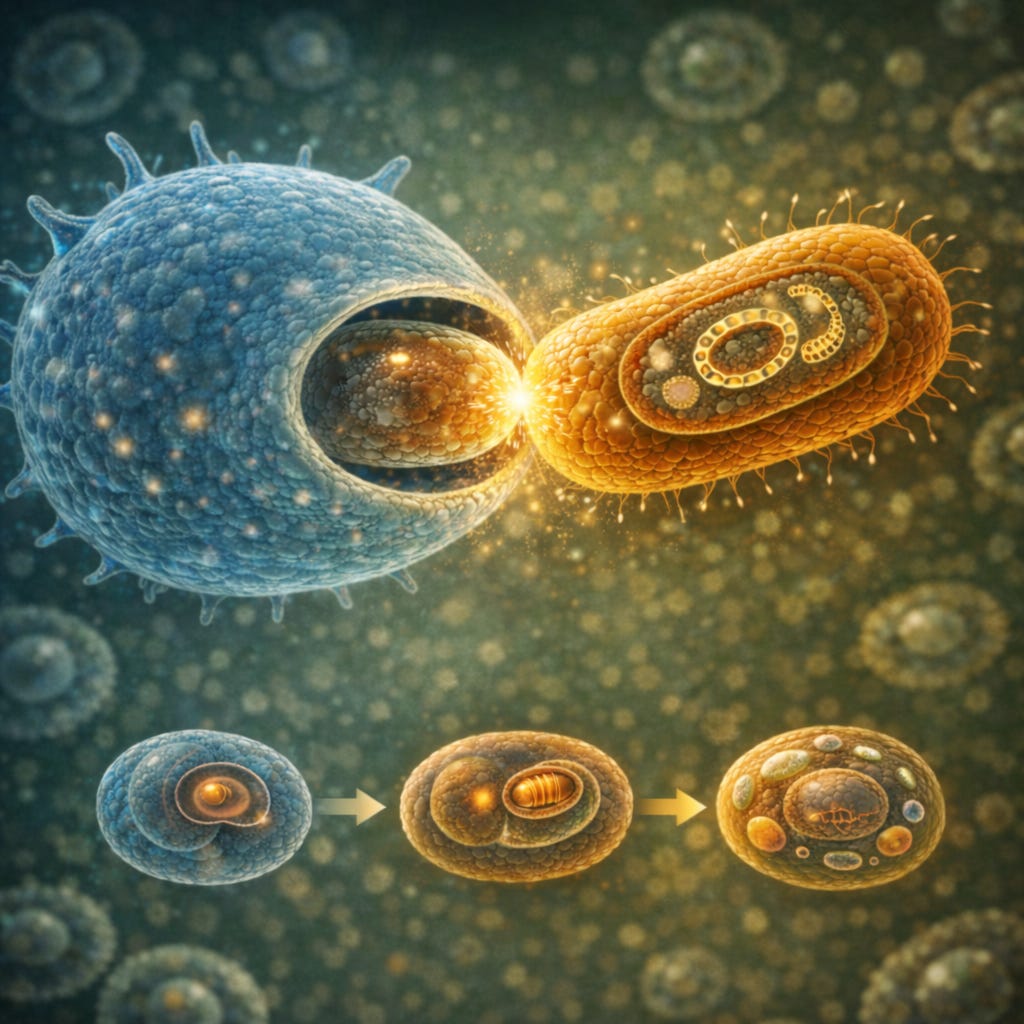

The symbiosis at the heart of our cells

We tend to think of our cells as singular entities. The reality is that in each of our cells there are two different genomes collaborating. In addition to the one present in our cells’ nucleus, there is also the DNA present in mitochondria, the organelles in charge of producing the energy (ATP molecules) for the cell. These organelles, present in all eukaryotic cells (those of all animals, plants, fungi, and many single-celled organisms), are widely understood to be the remnants of an ancient bacterium absorbed by a cell and maintained in a symbiotic relationship.

The proteins that mitochondria need are largely encoded in the nucleus. The nucleus sends the instructions, the cell builds the proteins in the cytoplasm, and those proteins are imported back into the mitochondria. Meanwhile, mitochondria provide the energy that makes the whole operation possible. This division of labour within eukaryotic cells is one of the bases of complex multicellular life on Earth.

How cooperation is sustained. Because mitochondria have their own genome and replicate within cells, there is always a risk of cheating: some variants can favour their own proliferation even if that undermines cellular performance. The nucleus needs mitochondria to produce energy rather than prioritise their own replication. This is what economists call a principal–agent problem, where a principal relies on an agent to perform a task even though the agent’s incentives may not be fully aligned with the principal’s. Evolution has solved this problem by putting mitochondria under nuclear control and surveillance. Mitochondria depend on nuclear-encoded machinery, dysfunctional ones are preferentially cut off and removed by cellular quality control.

Stronger together: the emergence of multicellular organisms

After joining forces within cells, cells also “found out” that working together can be good for replication, and therefore for the genes they host.

Multicellularity likely started with simple clumps of cells staying together, sometimes in structures resembling microbial biofilms, where cells are glued together by a matrix of secreted molecules. One main benefit is a reduced risk of predation. Modern laboratory evolution experiments show that multicellular clumps are more likely to form when a predator is introduced into the environment.2 The mechanism is simple: clusters are harder to eat. Becoming larger, even crudely so, can be enough to survive.

But once cells remain together across generations, new possibilities open up. Some cells can specialise. Others can protect, transport, or support. What begins as a simple size advantage becomes a platform for internal division of labour and more complex organisation, eventually supporting the evolution of large multicellular organisms.

How cooperation is sustained. Multicellular organisms are complex things, but cooperation within them is relatively easy to maintain because cells share the same genes. They are clones, so their genetic interests are aligned. That is why nearly all cells in your body are set up to live and die selflessly, only so that your gametes can produce new organisms.

Interspecies cooperation

Once cells are united into multicellular organisms, another level of cooperation becomes possible: between organisms. Interestingly, such cooperation emerged even between organisms that are not closely related and belong to different species.

A classic example is the relationship between plants and fungi. Most plants rely on mycorrhizal fungi that attach to their roots. The fungi extend the plant’s reach into the soil, improving access to water and nutrients such as phosphorus. In return, the plant supplies sugars produced by photosynthesis.

Another well-known example is cooperative interactions between different fish species, such as cleaner fish and their clients. Cleaner fish remove parasites from larger fish, gaining food while providing a service. Clients choose which cleaners to visit and abandon those that cheat. Cleaners, in turn, adjust their behaviour to maintain a good reputation.

Many ecosystems depend on cross-species partnerships. In particular, more than 80% of land plants form mycorrhizal associations, which makes this one of the most widespread symbioses on Earth.

How cooperation is sustained. Because the partners are not genetically aligned, interspecies cooperation is always exposed to cheating: one side can take the benefit while reducing what it provides in return. What keeps this in check is strategic enforcement. Partners can stop cooperating, switch to alternative partners, or reduce the flow of benefits to poor performers. Plants, for instance, can shift carbon towards fungal partners that deliver more nutrients and away from those that deliver less, while fungi can preferentially supply hosts that provide more carbon. In cleaner-fish systems, clients simply leave and choose other cleaners, which makes cheating costly and rewards cleaners that maintain a good reputation.

Social animals

The benefits of cooperation are often easier to see within a species, especially when organisms live in small communities with close kin relationships. Social insects like ants and bees are a well-known case. Their genetic system can make sisters unusually closely related: in haplodiploid species, sisters can share around three quarters of their genes. That tends to align interests and can reduce some genetic conflicts, which makes cooperation easier to stabilise.

Cooperation also appears in many vertebrates, particularly those living in groups with repeated interaction and some degree of kin structure. Meerkats are a good example: individuals take turns acting as sentinels, watching for predators while others forage. Apes provide another set of examples, with grooming, alliance formation, and coordinated conflict. Among apes, humans pushed this further, relying on cooperation at a scale that far exceeds what our individual bodies would allow.

How cooperation is sustained. As with interspecies cooperation, cooperation within groups of social animals relies on strategic enforcement: cheaters can be detected and punished, excluded, or avoided in future interactions. Cooperation is also easier to sustain because many groups are kin groups, so members have partly aligned genetic interests. In social insects like ants and bees, haplodiploidy means full sisters can share around 75% of their genes, which makes their incentive to cooperate unusually strong and helps sustain extreme levels of cooperation.

Humans: the social brain advantage

Describing the ecological success of our early ancestor Homo habilis, E.O. Wilson said:

These slender little people, the size of modern twelve-year-olds, were devoid of fangs and claws and almost certainly slower on foot than the four-legged animals around them. They could have succeeded in their new way of life only by relying on tools and sophisticated cooperative behavior. — Wilson (1978)

The distinctive feature of human cooperation is that it can take place in large groups of strangers who are not closely genetically related, and therefore do not have closely aligned genetic interests.

This kind of cooperation is hard to achieve in new situations. It requires substantial cognitive work to understand the goals of others, to find mutually acceptable solutions, and to ensure that agreements are respected by all parties. The social nature of our environment is likely what created strong evolutionary pressure for improved cognitive abilities. Our ancestors faced an evolutionary arms race for cognitive capacities that help them take advantage of social cooperation and avoid being left behind or taken advantage of.

Those who were able to make friends, negotiate coalitions, and gain the trust of others were more likely to survive and leave offspring than those who did not. This is why the main driver of the outstanding ability of humans to reason was likely not to understand the world, but to understand and convince others.

How cooperation is sustained. Using their brains, humans have been able to sustain cooperation at a scale unmatched in the animal world, not just through one-on-one monitoring but through shared social rules that are followed and enforced collectively. This is a key insight from economist Elinor Ostrom. In potentially conflictual situations, humans show an ability to design and implement rules of cooperation, monitor compliance, and sanction defectors.3

Cooperation: what it is and what it means

Cooperation emerges at every level of interactions

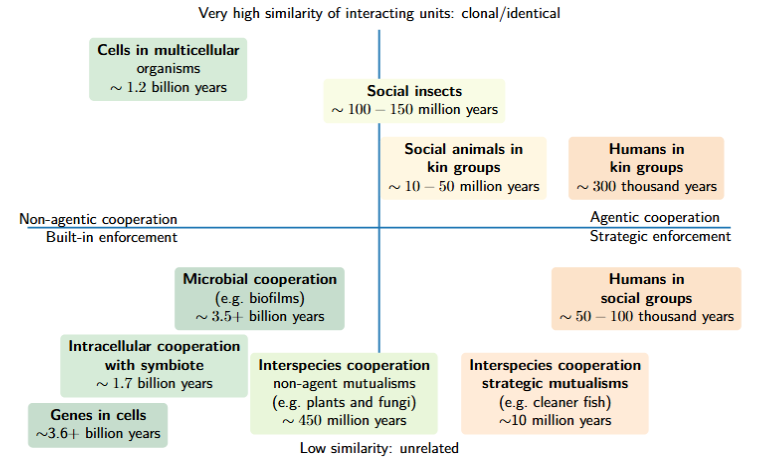

It is striking that cooperation emerged naturally at every step of life: genes cooperate in cells, cells cooperate in organisms, organisms cooperate in groups. The repeated emergence of cooperation at each level of organisation is one of the most striking phenomena generated by evolution. Cooperation is a scaffolding principle of life. Without it, nothing like the living organisms we observe would exist.4

What insights can we take from this reality when thinking about what it means for human societies?

The illusion of a Hobbesian state of nature

The idea that a population of self-driven agents trying to get the best outcomes for themselves would be locked into a perpetual war of all against all misses that one of the best ways to thrive, even in a competitive environment, is cooperation. This is illustrated in one of the scenes of The Hunger Games, which purports to represent exactly a battle royale, a fight of all against all. As Peeta enters the training centre with Katniss, he reminds her of the importance of forming alliances:

Remember, Katniss, today’s about making allies. - Peeta Mellark in The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013)

The fact that one can be stronger together has not been lost by evolution. It has found architectural solutions to make cooperation between replicating units work and be resilient to attempts by some units to break cooperation to their advantage.

The Hobbesian state of nature is a misleading idea. It never existed, neither between humans, nor between other living organisms.5

The illusion of unconditional cooperation

While the pessimistic cynicism of the Hobbesian state of nature is misguided, another possible error is to take an overly idealistic view of cooperation, hoping for people to always be kind and cooperative with each other.

While cooperation is everywhere in life, it emerged not from unconditional altruism among cooperating units, but from the mutual advantage they gain from cooperating. As Raihani said in an interview:

Cooperation evolves because it allows entities to get ahead. And in the end, on a genetic level, there have to be somehow benefits that either derive back to the individual, or via its relatives, for cooperative strategies to be under positive selection. — Raihani6

Because units cooperate to get ahead, their divergent interest is always a possible threat to cooperation.7 Therefore, whenever cooperation is stable, it is kept in place by mechanisms that prevent deviations and organise the split of the gains from cooperation between units that each would benefit from getting a larger share of the collective benefits.

The implications of these insights for political ideologies’ take on cooperation

Because navigating social cooperation is required for humans to succeed in life, our evolved moral sense values cooperation. And, likely because being seen as a strong cooperator is advantageous in society, we like to think (possibly to convince others) that we are strong cooperators. Hence, the view that we should all just be nice with each other, and that cooperation should be pursued as an absolute “Good”, may have an intuitive appeal. This could help explain the recurrent appearance of collectivist ideologies in history, from the Essenes in ancient Judaea, to the Taborites in early 15th-century Bohemia, to the Diggers in mid-17th-century England, and later to communism in 19th-century Europe.8

Religions and political ideologies that simply call for humans to be good are not offering sustainable social solutions because cooperation requires mechanisms and institutions in place to keep individual conflicts of interest in check. Without these, attempts at unconditional cooperation are bound to fail, as illustrated by unsuccessful attempts at socialism, from kibbutzim to large national states.9

However, the total opposite view, which would deny the importance of cooperation and the tremendous gains reached through collective action, is also misguided. In a famous speech, the British and conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher once said:

There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families. — Thatcher (1987)

This view is like saying that there are no cells, just genes. But, in the same way as genes were able to do much more by joining efforts into cells, humans have been able to do much more by cooperating together in large social groups. Indeed, it is only their ability to cooperate that made humans take over the world.

Evolution is too often described as implying only a competition between individuals. Contrary to this view, it is important to see how evolution has driven the emergence of cooperation at all levels of life because individual units can often be much more successful working together.

Appreciating the centrality of cooperation as a scaffolding principle of life is not naively idealising it or calling for it to happen out of sheer altruism in society. The lesson for us is twofold: cooperation can be highly beneficial, but it needs carefully crafted solutions to keep in check the individualist tendencies of cooperating agents. Evolution took eons to stumble on such solutions. Humans are in a unique position to use their agency and their cognitive capacity to engineer cooperation. The key challenge is to find institutional solutions to leverage the gains from cooperation and limit conflicts. What these institutions can be will be the topics of future posts in this series.

References

Boraas, M.E., Seale, D.B. & Boxhorn, J.E. (1998) ‘Phagotrophy by a flagellate selects for colonial prey: A possible origin of multicellularity’, Evolutionary Ecology, 12, pp. 153–164. doi:10.1023/A:1006527528063.

Dawkins, R. (1976) The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Engels, F. (1859) Letter to Karl Marx, 11 December 1859, in Marx, K. and Engels, F. Marx and Engels Collected Works, vol. 40: Letters 1856–1859. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Engels, F. (1875) Letter to Pyotr Lavrov, 12–17 November 1875, in Marx, K. and Engels, F. Marx and Engels Collected Works, vol. 45: Letters 1874–1879. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Huxley, T.H. (1893) ‘Evolution and ethics’ (Romanes Lecture, 1893), in Huxley, T.H. (1894) Evolution and Ethics and Other Essays. London: Macmillan.

Leigh, E.G. (1971) Adaptation and Diversity: Natural History and the Mathematics of Evolution. San Francisco: Freeman, Cooper.

Marx, K. (1861) Letter to Ferdinand Lassalle, 16 January 1861, in Marx, K. and Engels, F. Marx and Engels Collected Works, vol. 41: Letters 1860–1864. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Ostrom, E. (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Raihani, N. (2021) The Social Instinct: How Cooperation Shaped the World. London: Jonathan Cape.

Raihani, N.J. and Power, E.A. 2021, ‘No good deed goes unpunished: the social costs of prosocial behaviour’, Evolutionary Human Sciences, vol. 3, e40.

Sahlins, M. (2008) The Western Illusion of Human Nature: With Reflections on the Long History of Hierarchy, Equality and the Sublimation of Anarchy in the West, and Comparative Notes on Other Conceptions of the Human Condition. Chicago, IL: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Thatcher, M. 1987, Interview for Woman’s Own, 23 September.

Wilson, E.O. (1978) On Human Nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Note that, contrary to what one may think, given that Darwinism is seen with some concerns about its potential political implications in parts of the left, Engels and Marx had very positive views about Darwin. Engels wrote to Marx:

Darwin, by the way, whom I’m reading just now, is absolutely splendid… One does, of course, have to put up with the crude English method. — Engels (1859)

Darwin’s book is very important and serves me as a basis in natural science for the class struggle in history […] — Marx (1861)

Boraas et al. (1998).

Ostrom (1990).

Tibor Rutar has a very good post on how a gene-centric theory of evolution explains all the “altruistic” behaviour we can observe in society. He presents theories and ideas I will discuss in later posts.

https://thebiologist.rsb.org.uk/meet-our-members/nichola-raihani-interview

Except in the cooperation of clones, such as the cells in multicellular organisms, which have identical genetic material and therefore perfectly aligned genetic interests.

However, within these cells, cooperation is not perfect. Within organisms, genes can have opposing interests. For instance, during gestation, paternally inherited alleles in the fetus may favour greater maternal investment, whereas maternally inherited alleles may favour less.

Dan Williams wrote an interesting criticism of socialism, arguing that some socialist arguments take our self-deceptive tales about unconditional cooperation at face value, illustrated through a discussion of philosopher G. A. Cohen.

A further clue that “unconditional” cooperation is not a stable human default is that extreme prosociality can actually attract suspicion or backlash. People sometimes react negatively to unusually generous individuals, especially when the behaviour seems well beyond what is compatible with the person’s own interest. People who see someone giving all their time and money to others often do not think “wow that’s great” but “what’s wrong with this person?” As Raihani and Power note, “excessively generous individuals risk losing their good reputation, and even being vilified”.

I like the recap of cooperation types across time and at different scales, it provides a good overview to situate the usually human-centered studies of the evolved psychology of cooperation.

Some great uncommon examples!

I think people often have the wrong picture of 'evolution' as purely selfish, largely because of the misleading 'selfish gene' idea. We shouldn't view genes as the only true replicators. Instead, ‘multi-level selection’ suggests that cells, organisms, and groups of organisms also count as replicators - all nested within each other like Russian Dolls.

Inside a single Russian doll, the inner units usually cooperate because they rely on each other (intra-cooperation), but conflict arises if a single unit starts reproducing selfishly at the expense of the whole (intra-conflict). Between two separate Russian dolls, they might work together for mutual benefit (inter-cooperation), or fight over limited resources (inter-conflict).

Admittedly, when I picture evolution, I usually only think of that last dynamic, the classic 'dog-eat-dog' struggle, completely forgetting the other three. I only realized this thanks to the great book 'Evolution and the Levels of Selection' by Samir Okasha.

Here I ramble more about 'multi-level selection' but in regards to actual examples like cancer, culture, kin selection... if you are interested: https://paleoposition.substack.com/p/critiquing-veritasiums-video-on-evolution