Intermezzo: How much can you trust fancy behavioural findings?

A new scandal hits the field of behavioural research

A new scandal is shaking behavioural research. A well-known paper on honesty, which included a study involving Dan Ariely that had already come under scrutiny two years prior, is now back in the spotlight due to likely fraud. This time, by another team of researchers.

The team at Datacolada used forensic-like skills to delve into hidden layers of the paper's data, which was housed in an Excel file. They showed that rows had been manually altered, to foster a strongly significant result. One of the most damning aspects pointed out by Datacolada is that the two teams involved in the various studies of the paper operated independently, as confirmed by one of the researchers.

The fact that two independent teams seem to have fabricated studies within the same paper raises questions about the extent of forgery within the research area as a whole. At best, it suggests this isn't an extremely uncommon practice. So, what should we make of it?

Questionable research practices and the replication crisis

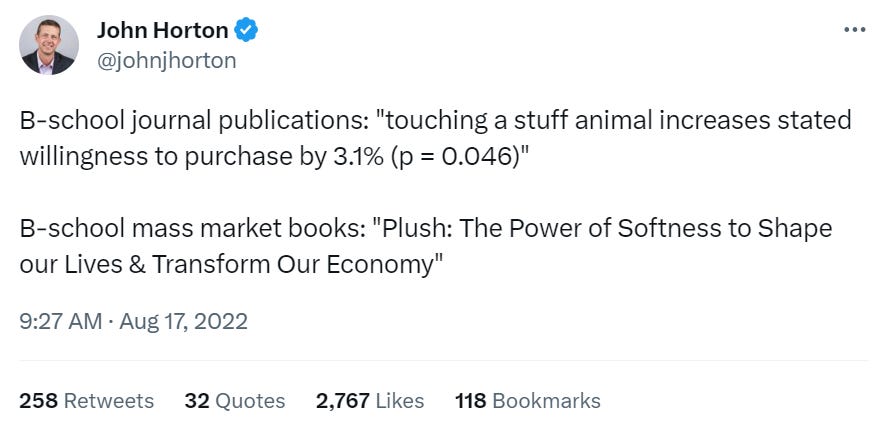

Evidently, this is worrying for the field as a whole. In fact, it's likely just the tip of an iceberg of problems, also hinting at widespread questionable research practices. Human psychology and behavioural research are often characterised by large rewards for a “wow” factor: minuscule interventions having significantly large behavioural impacts. Examples include the suggestion that holding a warm coffee can make people warmer in social interactions, or that adopting a macho-like pose in your office for a minute can increase your testosterone level and confidence before your next important meeting. These results, published in leading scientific journals and attracting a multitude of citations, often lead to book contracts and business lectures discussing the implications of the findings.

The questionable research practices are now well known. Even without explicit fraud, they skew the balance towards concocting striking results from nothing. One widely used strategy is to conduct a multitude of studies, discarding those that aren't significant and publishing the few that are significant due to chance.

Another practice involves segmenting and slicing the data until you find a significant result in some subgroups. Was your overall effect not significant? Try to see whether it is significant for men or women, rich or poor people, young or old people, etc. As a reader, if you come across a paper finding interesting results “only for this group”, and the authors hadn't previously stated their particular interest in this group, be sceptical. You won't know how many subgroups were analysed before this one was found to be significant.

As a result, when highly impressive effects are published in high-impact factor journals, later replications often find smaller or no effect and end up being published in less impactful journals. This phenomenon is referred to as the “decline effect”.

The behavioural disciplines within business schools appear to be particularly affected by these practices. The proportion of “findings” in leading marketing journals that other researchers can later replicate is, for instance, alarmingly low.

Is behavioural research, and behavioural economics in particular, worthless?

So, does this mean all behavioural research is worthless, including behavioural economics, which has recently been labelled as a dead discipline?

My perspective is less pessimistic. For one, it appears that behavioural economics hasn't been as plagued with such practices. A replication of many papers in experimental economics published in Science found a higher proportion of studies being replicated than in psychology. Although the situation isn't perfect, it doesn't seem as dire as the one that has hit the field of psychology with the “replication crisis”.

There are at least two reasons why economics is faring better than psychology in behavioural research. Firstly, a practical reason: economists pay participants a reasonable sum of money to take part in their experiments. This, by default, makes it costly to run a large number of studies to pick the only ones working. Secondly, economics as a field is characterised by widely accepted theories that limit the acceptance of surprisingly new and unexpected results. This point is clearly put by Michael Muthukrishna and Joseph Henrich who describe the lack of a unifying theory in psychology as one of the factors at the root of the replication crisis:

Without an overarching theoretical framework that generates hypotheses across diverse domains, empirical programs spawn and grow from personal intuitions and culturally biased folk theories. - Muthukrishna and Henrich (2019)

In summary, there is more freedom in psychology to come up with very surprising effects. These surprising effects face less resistance for being difficult to believe given what is commonly accepted about human behaviour in the discipline.

There's another reason why we should not be overly dismissive about the majority of empirical findings in behavioural economics. When early behavioural economists like Kahneman, Tversky and Thaler published their findings in economic journals, their ideas were outside of mainstream economics. Behavioural economists were subject to a greater level of scrutiny and criticism from established journal editors and reviewers. At the time, publishing surprising results that contradicted the views held by most economists required significant effort and perseverance. The empirical patterns revealed by behavioural economists in the early stages of the behavioural revolution—such as reference-dependence, apparent deviations from proper probabilistic reasoning, and inconsistency of preferences across time—have proven robust to replications.

The context of these findings was markedly different from the one in psychology departments and business schools later on where finding quirky, surprising results became rewarded. It is in this later context that these instances of likely fraud have been discovered.

What next?

The fields of psychology and behavioural economics are adopting new research rules to prevent questionable research practices. The ESA, the international association of experimental economists, has actively contributed to this evolution and commissioned a report on this matter in 2021, of which I was a co-author.

Among the encouraged practices is the pre-registration of studies, where researchers publicly announce what their study will entail and what specific questions they will investigate. Pre-registration eliminates much of the flexibility researchers could use to turn a non-significant result into a significant one. In a revealing study, it was found that when medical studies began using pre-registration, they went from 57% of drug trials finding a significant effect to only 8%!

Additionally, there's an increasing sentiment that research in behavioural economics has become too a-theoretical. The abundant challenging behavioural findings have profoundly transformed economics. But while the appeal of the traditional mainstream theories has faded, they haven't been replaced by a new and coherent theoretical framework. One can sense a longing among behavioural economists for a more integrated theoretical understanding of the discipline. Ran Spiegler recently articulated this viewpoint explicitly:

This is a view I share, and it partially motivated my book, “Optimally Irrational”, in which I highlight many recent theoretical developments that help make sense of a range of seemingly surprising behavioural findings. It's also a perspective that informs this Substack, looking at the good reasons behind our seemingly puzzling behaviours.

In conclusion: No, behavioural economics is not dead, and behavioural research is not worthless. However, some of it has indeed been overhyped in recent years. So, if you hear about a flashy behavioural finding that seems too good to be true, well, maybe it isn't...1 But with better empirical research practices and a renewed focus on theoretical explanations, behavioural economics will move away from the issues discussed here.

This intermezzo appears amid a series of three posts, in which I reassess well-known “biases” as behavioural patterns that may, in fact, have good reasons. The next and final post in the series will delve into Kahneman and Tversky's most significant contribution to behavioural economics: reference-dependence (the sensitivity to gains and losses). You can subscribe to receive notifications of future posts. The content of this Substack is free.

Interestingly, when economists were asked which published results were most likely to replicate, they assigned lower chances of success to the studies that indeed ended up not replicating.

Behavioral economics is, basically, social psychology (which has the worst replication rate in the behavioral sciences). It shouldn't be lumped in with econ.

1. I would distinguish between behavioral economics and experimental economics

2. The problems seem to arise mostly in behavioral economics (BE)

3. The deeper problem seems to be that BE is presented as a research program, but it is a political project. More precisely, as I have been trying to argue for a while, BE has an exoteric program (provide an empirical foundation to the study of human economic and strategic behavior) and an esoteric one (destroy the foundation of rational choice and thus of economics as a science).

I can elaborate….

Aldo Rustichini