Hamas, the left, and the inconsistency of political beliefs

How our coalitional thinking shapes our political thinking

TLDR: The positions of many left-wing activists and organisations after the attack on Israeli civilians strikingly illustrate the social logic of our political beliefs. We hold beliefs as part of groups to which we belong. Due to historical contingencies and conflicting incentives, a group’s position is often inconsistent in many ways. Through motivated reasoning, we gloss over inconsistencies to maintain our commitment to the group’s positions.

When we have political beliefs, we tend to think that these beliefs reflect our inner values/thoughts. From these values, there follow our decisions to back issues and to vote for some parties. This vision is to a large extent an illusion that does not correspond to how we form and retain our political beliefs. One of these challenges is why these beliefs tend to be inconsistent in often very prominent ways.

Inconsistent beliefs

We tend to think that we hold political beliefs because they make sense together; they reflect some inner logic given our values. However, it is striking to see how inconsistent they can be. In the US, for instance, the same people can defend a ban on abortion to save lives and oppose regulation to buy and carry firearms, that are regularly used in the US for mass killings of civilians, including in schools.

This week has provided us with another example of the inconsistency of political preferences, this time on the left side of the political spectrum, after the tragic events that took place in Israel. Hamas militants attacked a music festival in the South of Israel, killing hundreds of civilians, including children, parading some of their lifeless bodies on TV and abducting more than a hundred of them, including many women and children, back to the Gaza Strip.

The international reaction has understandably largely been shock and horror as a stream of videos appeared on social media showing innocent young people, some favourable to a peace process between Israel and Palestine, being killed and abducted. The reactions in some parts of the left in Western democratic countries were, however, very different. Instead of criticising the attack, they criticised Israel for the process of occupation of Palestinian territories.

While leftwing ideas are generally associated with a support for peace, and the defence of innocents, there was at best a restraint in the condemnation of the event. Online, several academics pointed out that “decolonisation”, a term widely used in the fields of critical studies, does not just mean changing the academic syllabus. The unspoken implication seems to be that “decolonisation” can, or has to, come with the deaths of civilians of all ages and genders.

In the following days, leftwing organisations participated in demonstrations, organised in favour of the Palestinian movement, just after the attack. In one of them in Barcelona, LGBT flags were waved among Palestinian flags.

Commenting on a demonstration in Sydney and criticising the fact that the Opera House displayed the Israeli colours, a leftwing activist connected the Palestinian cause to the indigenous cause in Australia.1

In more than one of the gatherings that took place right after the massacre, apologies for the terrorist attack, or downright antisemitic chants took place. How can criticising violence on the part of Israel go hand in hand with being seemingly complacent with violence against Israeli civilians? What are the moral grounds used to generate the logic behind these positions? And what about the strange association between highly culturally liberal ideas, like LGBT rights, with the highly conservative Hamas government? Amnesty International assessed that, in the Gaza Strip, homosexuality is illegal and can lead to 10 years in prison.

How can such political ideas be bedfellows? It may seem like a puzzle, but it is actually very easy. The idea that we hold consistent political beliefs is, for the most part, an illusion.

Reasoning as lawyers

As we examine our beliefs, consider the following: there are many types of political issues: economic issues, social issues, moral issues, defence issues, geopolitical issues, and environmental issues. For each type of political issue, there may be two or more major questions. For instance, on environmental issues, you can be for or against nuclear power, you can be for or against strong measures to quickly reduce the CO2 emissions of your country, you can be for or against regulation restricting pesticides in agriculture. The positions on each of these questions are not necessarily clearly logically related within a type of issue. The positions on questions across different issues (e.g. environmental vs geopolitical) are even less clearly logically connected.

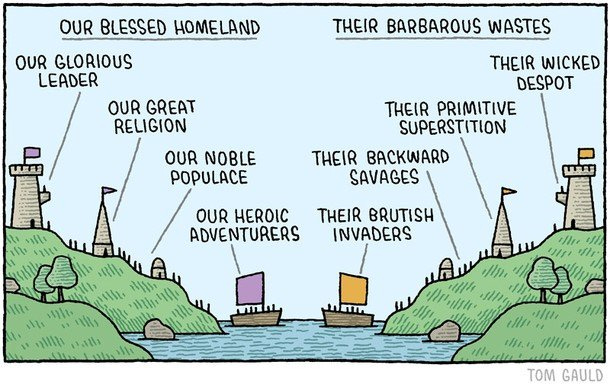

In most countries, the political space is however divided between two sides, often represented by a left-right dimension. Consider all the positions possible on all the issues present in political discussion. What are the odds that the positions on all questions would logically bundle themselves neatly in a left-right dimension? For example, what are the odds that opposition to abortion, opposition to gun control, the defence of Christian values, an opposition to vaccines and an opposition to funding the war in Ukraine would logically bundle on the right while a support for LGBT rights, moral support for Palestinian organisations, an opposition to nuclear power would bundle logically on the left of the political spectrum?2

This question is even more reasonable to ask when you observe that the left-right spectrum does not feature the same positions across different countries. Some positions held by some left-wing parties in some countries are opposed by other left-wing parties in different countries (the same is true for right-wing parties). Positions also change over time, with some political positions being supported and later rejected by a given party (this happens on each side of the political spectrum).3

These facts seem puzzling because we tend to think that our positions are the result of our intellectual reasoning and that our reason is a faculty designed to help us find what is right. In that perspective, reasoning leads us to adopt the political ideas we have because they make sense together. But recent work in behavioural science suggests a very different reality. Reason is not a faculty designed for us to be right, but for us to be convincing. This point was made by Dan Sperber and Hugo Mercier in their 2017 book The Enigma of Reason.

They point out that our ancestors were not selected for their prowess in abstract logic, for their ability to solve geometric problems, or for their skill in identifying inconsistencies in different moral philosophies. Our ancestors were selected for being able to convince others to trust them, work with them, and side with them in conflicts. To convince others, our arguments need to be congruent with reality. If I tell you that you should join my band because we are stronger and more trustworthy than others, you will want to compare that claim with past evidence of our past successes and loyal behaviour. To convince others we therefore use reason to put forward compelling arguments consistent with the available evidence. In turn, others use their reasoning skills to exert epistemic vigilance to assess whether the claims being made make sense.

The first piece of the puzzle is that we do not use reason as scientists, but as lawyers, trying to gather the evidence to make the most compelling case.

Coalitional thinking

The second piece of the puzzle is that we are members of social groups and that the moral principles we adhere to define who we are and with whom we side. Our psychology is thus heavily influenced by coalitional thinking. We have a vested interest in defending some ideas not just for their inherent worth, but because they are those of the community to which we belong.

In the political arena, political parties and their supporters compete to gain public support. The bundle of political positions held by these parties must have some consistency as inconsistency makes it harder to convince others. In the same way, a lawyer will have a stronger case if the different arguments he/she puts forward are consistent. But consistency is not a necessity.

There are at least two reasons for the existence of inconsistency within a group's set of positions. First, the adoption of a new position is not necessarily contingent upon its compatibility with existing positions; this process often contains an element of randomness. For example, if a position is favoured by some members of a party and is also popular among external voters, it may gain enough traction to be included in the party's agenda, regardless of whether it aligns with other, less salient positions. If inconsistencies are later identified, efforts may be made to reconcile them or obscure their implications.

Second, more than consistency, an underlying motivation associated with political thinking is group loyalty. Hence when encountering a new argument, we often do not really ask ourselves “is this a good logical argument?” We actually ask, “Is this argument compatible with or incompatible with our group’s ideas?” By extension, we often attempt to discern whether the argument suggests the person making it is “with us or against us.” The answer to these questions will go a long way towards explaining whether we are inclined to accept the argument, regardless of whether it is solid or not based on evidence and logical consistency.

Our loyalty to our existing group also means that when people from our group say something new or do something new, we will be inclined to defend their positions against criticism. A recent study suggests that our moral positions make us more prone to engage in motivated reasoning (Cusimano and Lombrozo, 2023). We buttress our side with arguments that may be weak while being more critical of the quality of the opposition’s argument. Motivated reasoning, often employed in the defence of a group’s interests, can lead us to uphold principles selectively. We may criticize members of opposing groups for certain actions while excusing similar actions undertaken by individuals on our side.4

This coalitional mindset and the way our reason actually works explain, in a broad sweep, a wide range of seemingly strange patterns observed in political debates. In particular, it explains why left-wing activists professing an attachment to the moral principle of peace and freedom ended up siding with organisations that are openly illiberal and kill civilians. A credible dynamic works as follows: witnessing Israeli colonisation and victims on the Palestinian side and the US support for the Israeli government makes support for the Palestinian cause consistent with a defence against oppression and what is seen as an imperialist role of the US government in the world. But once this coalition is set, if some Palestinian organisation commit terrorist attacks against Israeli civilians, the members of leftwing groups who support the Palestinian cause will not look at it abstractly, but as an us-vs-them question. There will be a tendency to deny the extent of the violence, or rationalise it (“violence begets violence”).

From an intellectual consistency point of view, a position like the one articulated by Antonio Guterres, the Secretary General of the United Nations—to recognise legitimate grievances of the Palestinian people and also condemn the attacks—could seem to make sense. However, the coalitional logic of political beliefs makes such positions harder to emerge in political groups that have long-standing support for the Palestinian cause, as it would require taking a critical stance against parts of the established coalition and in favour of parts of an antagonistic coalition.5

Conclusion: Moral high ground?

We tend to think that our moral principles lead us to adopt good positions and be cooperative and mindful of others. But the reality of human psychology is that we do not just hold moral principles for their own sake, but also because they reflect our membership and loyalty to some social groups.

While moral principles can help us be cooperative within our group, they can also justify us being conflictual with others outside of our group. Discussing the case of religion, Blaise Pascal famously said: “People never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from a religious conviction” (Pensées 1670). Because moral emotions likely have a role in fostering in-group cooperation,6 the feeling of having the moral high ground can motivate people to act decisively to punish others for their moral positions that are judged inferior. A key lesson of these insights from behavioural sciences is that we should question our feelings of moral high ground that make us feel that our position is more worthy than others.

References

Cusimano, C. and Lombrozo, T., 2021. Morality justifies motivated reasoning in the folk ethics of belief. Cognition, 209, p.104513.

Mercier, H. and Sperber, D. eds., 2017. The enigma of reason. Harvard University Press.

Pascal, B., 1670. Pensées.

“Gadigal” is a reference to the Gadigal indigenous people.

Formally, you can think of all the possible political positions as a multidimensional space, each position creating one dimension. The bundling of these different positions in only two parties on a left-right dimension suggests that this multidimensional space can be mostly projected on a left-right line, a unidimensional space. What are the odds of this?

In some countries, right-wing parties strongly promoted vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic, favour helping Ukraine, and support LGBT rights, while in other right-wing parties were against these. Similarly, in some countries, left-wing parties oppose nuclear power, the regulation of the Muslim veil in public spaces, and the policies to limit immigration, in some other countries, they take opposite positions. These differences in positions are not just across countries but also across time in a given country: the Labour Party in the UK was initially against membership in the European Community and became favourable to it. The Democratic Party in the US was initially in favour of slavery and later carried the civil rights movement.

This logic, like the whole point of the post, is valid for both sides of the political spectrum.

Similarly, those who were shocked by Hamas’ attack may find it harder to also be critical of the Israeli government if its military operation leads to the death of many civilians in the Gaza Strip.

A point I developed in Optimally Irrational (the book).

Preach! And: https://tempo.substack.com/p/are-we-the-baddies?utm_source=publication-search

Cognition and morality are social. Typically we belong before we believe and we behave.

The thing about coalitional thinking is that it is more destructive the stronger and fewer the coalitions are. If there are many weak coalitions then you can slip and slide between them. If there are only two and they are absolute - i.e. a Schmittian Friend/Enemy - then the chances of you revising your priors are decreased.