Discussion with Steve Stewart-Williams on evolutionary psychology

He answers my candid questions about the discipline

Today, I am glad to share a discussion with Steve Stewart-Williams on Optimally Irrational. Steve is one of the most well-known evolutionary psychologists on social media, with a large following on Twitter and Substack. He is the author of an excellent book, The Ape that Understood the Universe, that provides an accessible overview of how evolution helps us understand human behaviour. I invited him to answer my candid questions about evolutionary psychology.

LP: Hi Steve, thanks a lot for taking the time to join me and answer my questions about evolutionary psychology. To start, how would you define evolutionary psychology?

As I see it, evolutionary psychology is just regular psychology, but testing hypotheses derived from theories in evolutionary biology. When I describe it this way, though, I’m usually met with blank stares. It’s too abstract. So, my favorite way of explaining to people what the field is all about is to ask them a series of questions.

The first is: Why do lions have sharp teeth? Why did sharp teeth evolve? The answer, of course, is that they evolved to help lions to catch and devour their prey.

The second question is: Why do gazelles have fast legs? Why did fast legs evolve? And the answer this time is that they evolved to help gazelles to escape the clutches of lions and other hungry predators.

This gets people into the spirit of adaptationist reasoning. I then explain that evolutionary psychology takes this explanatory framework, and applies it to the mind and behavior.

To show how, I start pelting my victims with questions again. Here’s an example: Why do people have the capacity to experience pain? Simple: Pain motivates us to escape or avoid tissue damage – to get the clothes peg off our nose, for instance, or our hand off the top of the stove. Another example: Why do we have hunger and thirst? Again, simple: to motivate us to eat and drink. And so on.

If my listeners haven’t nodded off by this point, I wrap up by explaining that evolutionary psychologists don’t think that everything is an adaptation – just the fundamental constituents of the mind. And part of the project of evolutionary psychology is to figure out what’s fundamental and what’s not.

LP: Evolutionary psychology is often criticised for not being scientific. It’s accused of producing ex post “just-so stories” that rationalise conveniently some observed behaviour with hypothetical scenarios. In addition, it is often said that it cannot make predictions and in that sense is not a proper scientific approach. What do you think of these criticisms?

Well, to be as fair as possible to the critics, I do think that evolutionary psychologists sometimes come up with dodgy adaptationist explanations and accept them based on flimsy evidence. But that’s a problem with specific claims and papers, not with the basic logic of adaptationist explanations. Plenty of research in evolutionary psychology avoids these pitfalls, and is persuasive to anyone who doesn’t have an axe to grind with the field.

My favorite examples include research on sex differences in traits such as sexual inclinations, mate preferences, and aggression, and research on altruism among genetic relatives vs. non-relatives. In both cases, the research in question is based on well-established theories from evolutionary biology, and aims to test predictions directly derived from those theories. And in both cases, the evolutionary explanations are supported by copious data—data showing, for instance, that men are more aggressive than women, and that people tend to favor relatives over non-relatives, all else being equal.

Critics might complain that we already knew that these patterns existed, and thus that evolutionary psychologists are just concocting just-so stories to explain them after the fact. Of course, exactly the same could be said of sociocultural explanations for the same phenomena. In either case, though, it’s fine to try to explain facts we’re already aware of. Science does it all the time; no one rejected the Copernican explanation for the phases of the moon, for instance, on the grounds that we’d already noticed them. You just have to go beyond the existing evidence to test your pet explanation.

In the case of evolutionary explanations for the sex difference in aggression, for example, we can look at whether the difference is found across cultures, whether it’s associated with prenatal hormonal exposure, and whether it’s found in other species with a similar evolutionary origin story to us. Spoiler alert: It is.

LP: When you look at evolutionary explanations, it is frequent to hear that we do not need to know the evolutionary origin of behaviour. We can just study human behaviour as it is and evolutionary explanations, while not wrong, are superfluous to understanding human psychology. What do you think of this criticism?

I agree that, for some purposes, we don’t need to know the evolutionary origin of behavior. To administer cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), for instance, we don’t need to understand the ultimate origins of our vulnerability to psychiatric distress. But I’d want to say three things about this claim.

First, the same is true of sociocultural explanations: For certain purposes, we don’t need to understand the sociocultural origin of behavior either. Strangely, people never use that as a reason to dispense with those explanations.

Second, the evolutionary origin of behavior is a scientific question in its own right; it’s not justified only by its relevance to other scientific questions. If your goal is to practice CBT, the evolutionary underpinnings of depression may be irrelevant. But if your goal is to understand the evolutionary underpinnings of depression, then CBT may be irrelevant.

Third and finally, in some cases, understanding the evolutionary origins of a trait may sometimes prove useful for understanding that trait and how to modify it. I’d argue, for instance, that an evolutionary approach can inform our understanding of depression and other psychological maladies by highlighting the importance to people’s happiness of evolutionarily relevant variables – things like having a romantic partner, having social support from close kin, and the like.

Sure, it’s possible to appreciate the importance of these variables without an evolutionary perspective. But an evolutionary perspective makes them more salient – and it also helps guard against our tendency to drift off into a concern with variables that probably aren’t so important.

LP: David Buss famously wrote in 1995 that evolutionary psychology provides “a coherent metatheory for the different branches of psychological sciences” and that it could become a unifying paradigm in psychology. Today, 30 years later, how do you think things have moved in psychology in its relation to evolutionary psychology?

I have mixed feelings about the idea that evolutionary theory could be a unifying metatheory for psychology. On the one hand, there’s a sense in which it has to be. Psychology is the study of the brain, mind, and behavior, and the brain, mind, and behavior ultimately trace back to natural selection. From that perspective, all psychology is evolutionary psychology. But this would apply to blank-slate psychology as much as to the kind of psychology done by evolutionary psychologists, so it’s a fairly weak claim.

A stronger claim would be that every area of psychology should be informed by a consideration of function, fitness, and other evolutionarily relevant considerations – or alternatively, that psychology will ultimately be reorganized in terms of clusters of adaptive tasks: staying alive, attracting a mate, raising kids, and so on.

The first thing to say about this is that it certainly hasn’t happened yet. Sure, there are some areas of psychology that it’s now hard to imagine without an explicit focus on evolution. This includes, in particular, the study of mate preferences and sexual behavior. But there are also plenty of areas where Creationists would feel as at home as evolutionists, because evolution just isn’t discussed.

The question then is whether this reflects a failure of psychology to adopt an evolutionary perspective, or whether it’s just that the evolutionary perspective is more useful in some areas than others.

I suspect it’s a bit of both. Functional reasoning could shed light on some areas of psychology that haven’t yet particularly embraced it – areas such as developmental psychology. In other areas, however, I’m not sure how much an evolutionary focus would contribute. Take the study of memory, for instance. It’d be interesting to see more explicit reasoning about why memory is structured in the way that it is—declarative memory vs. procedural, episodic memory vs. semantic, etc. But whereas an evolutionary approach offers entirely new explanations for phenomena such as sex differences and nepotism, I’m not persuaded it would do that for memory. The evolutionary angle would be an addendum, rather than a paradigm shift.

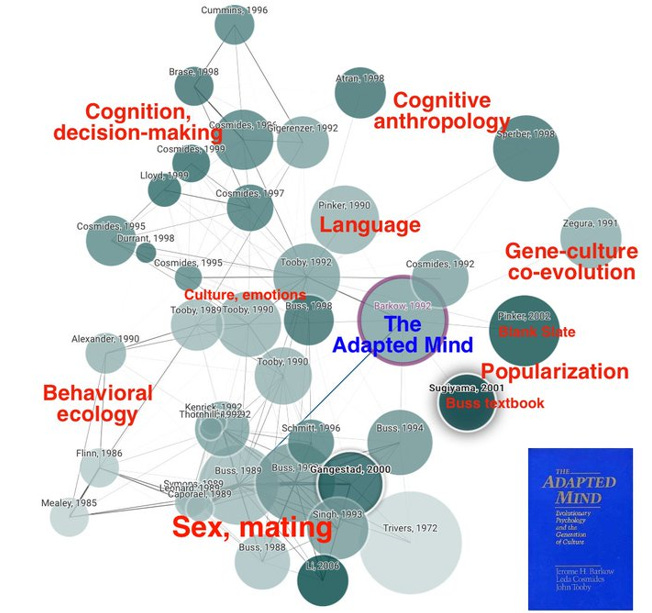

LP: I think there are different ways to define evolutionary psychology. In a general sense, it is the application of evolutionary principles to the study of psychological phenomena. But there is, I think, a narrower sense associated with the highly influential Santa Barbara school (following John Tooby and Leda Cosmides). What’s your view on this and on the different approaches in evolutionary psychology?

I favor the first definition. I’m not a fan of the distinction between broad evolutionary psychology and narrow evolutionary psychology. It comes mainly from critics of the field, who I think put much too much weight on some early papers by Cosmides and Tooby: two of the founders of the field and co-founders of the evolutionary psychology lab at UC Santa Barbara.

Those early papers laid out a number of principles that, in Cosmides and Tooby’s view, evolutionary psychologists should adopt – principles such as that humans are adapted solely to life as hunter-gatherers living in the Pleistocene savannah, that the mind is a collection of largely independent mental modules, and that these modules are always highly specific in the adaptive tasks they evolved to solve. The usual assumption is that all or most evolutionary psychologists signed onto those principles and continue to do so today.

I don’t think that’s accurate. For one thing, the field has changed a lot since those seminal papers were first unleashed on the world, and many of the early principles have been tweaked or even abandoned. Everyone in the field is aware, for instance, of the evidence for rapid, recent evolution, and thus few would argue that humans are adapted solely to the hunter-gatherer lifestyle or Pleistocene savannah.

In the same way, the notion of modularity is nowhere near as central to evolutionary psychology as many outsiders think. Critics talk about modularity a lot more than evolutionary psychologists do these days. Even Leda Cosmides has abandoned the term! And it’s not as if evolutionary psychologists were ever uniformly sold on the idea. As far as I’m aware, for instance, Martin Daly and Margo Wilson—also among the field’s founders—never embraced modularity.

Another reason I’m not a fan of the distinction between broad and narrow evolutionary psychology is that it’s too typological: It attempts to put categorical boundaries on what’s actually continuous variation. In doing so, it encourages an all-or-nothing attitude to the claims of so-called narrow evolutionary psychology.

Rather than seeing evolutionary psychology as a strict paradigm with a list of necessary and sufficient epistemological commitments, I see it as a loose collection of claims with a rough family resemblance to each other, which slowly evolves over time. Each of those claims should be judged on its own merits. To illustrate, when I read Cosmides and Tooby, I usually find myself thinking “Well, I agree with this, but not so much that.” Ditto the claims of any other psychologist, anthropologist, biologist, or philosopher writing about the implications of evolution for the human mind and behavior.

Other evolutionary psychologists do the same, no doubt – and different evolutionary psychologists make different judgements about the plausibility and importance of each of the claims in this area. In a sense, each has their own version of evolutionary psychology, which they continuously update as new evidence rolls in.

In my version, the central elements of the field are not massive modularity or exclusive adaptation to the Pleistocene savannah, but rather theories such as inclusive fitness, evolutionary mismatch, sexual selection, parental investment, and kin selection. To be clear, though, this doesn’t define an approach to evolutionary psychology, with people who weigh things differently staking out competing approaches. It’s a just a list of the ideas that I think are the most plausible and important.

LP: As you said, one theoretical idea that has become associated with evolutionary psychology is the idea of modularity (see Egeland 2024). We use cognitive “modules” that were selected by evolution to solve specific problems. I must say, I am not keen on this perspective. It suggests that the human brain is like a Swiss Army knife with specific cognitive processes to solve specific problems that were prevalent in the ancestral environment.

As an economist coming with a strong rational model, I think the module approach imposes cognitive limitations a priori—instead of showing that an optimal design would be modular (e.g. because of costs of multi-purpose cognitive processes). I am not convinced that general cognitive skills that can be repurposed across problems would not be selected.

Another issue with modularity is that, in practice, it may have facilitated the “just-so stories” produced in some parts of evolutionary psychology. Think of a problem? Come up with a “module” that in a hypothetical situation occurring in the ancestral environment would be a solution. I think it often dumbs down our perspective about human cognition. I do not think that modern neuroscience backs this approach and I feel it may be dated. Should evolutionary psychology keep this modularity approach? What do you think?

Like you, I’m not keen on the notion of modularity. I don’t find it a useful way to conceptualize the nature of psychological adaptation, and I don’t use the term module once in The Ape That Understood the Universe.

The modularity framework typically involves positing discrete mechanisms designed to address very specific adaptive tasks. My sense, though, is that things are a lot messier than that, with evolved psychological tendencies commonly cutting across multiple adaptive tasks and being favored by multiple selection pressures. Like you, I also don’t buy the idea that there are no general-purpose psychological adaptations but only highly specific ones. It seems much more likely to me that psychological adaptations differ in how general or specific they are, and that some – memory and abstract reasoning, for example – are very general in scope.

To be fair, there is plenty of specificity in the structure of the brain and mind. The pain system, for instance, is largely distinct from the emotion of fear. Perhaps, then, we could say that the pain system is one module, and the fear system another. But how is that any more illuminating than simply talking about the evolution of the pain system and the evolution of the capacity for fear? Describing these propensities as modules adds nothing – other than the baggage associated with the term.

LP: What do you think can be the greatest contributions of evolutionary psychology to psychology as a whole and to behavioural sciences?

To my mind, the greatest contributions are findings that stem from foundational theories in evolutionary biology such as sexual selection theory, kin selection theory, and reciprocal altruism theory – as well as findings focused on aspects of human psychology where we find strong parallels in other animals. These are the findings that I think are the sturdiest and least prone to the just-so-story accusation. They include basic emotions and motivations, basic sex differences, and our kin-altruistic inclinations.

I’d also add that, in a behaviorally flexible species like ours, evolutionary explanations do a better job of explaining our drives and desires than our specific day-to-day behaviors. Other than reflexes and stereotyped behavior like sneezing and laughing, most of our behavior is learned. Often, though, the motivations and goals that our learned behaviors are directed toward are part of human nature, rather than products of learning. For example, we learn specific ways to get food, but the desire to eat is part of human nature. It’s in explaining our drives and desires, rather than the details of specific behaviors, that evolutionary psychology has shed the most light on psychology.

LP: Geher and Wedberg (2019) noted that the EP field was disproportionately associated with the study of sex differences, possibly because its most influential textbook was written by David Buss who is an expert in mating and sexual behaviour. Geher and Wedberg suggest that, as a consequence, EP has faced opposition in some part of academia where there is a resistance towards the idea of sexual differences in behaviour. As an external behavioural scientist who believes that an evolutionary perspective should naturally be part of our conceptual framework, I share the view that the study of sexual behaviour and sexual differences occupies a disproportionately large place in the field compared to other central topics in psychology, such as cognition, strategic thinking, communication, and cooperation. What do you think of this criticism (if we can label this a criticism)?

I’m not too moved by the criticism. I think the main reason that evolutionary psychology is best known for the study of mating and sex differences is that these are among the areas where the approach has proven most useful – and for good evolutionary reasons: Sex and mating are absolutely crucial in evolutionary terms. Another reason these topics have hogged the limelight is that people find them inherently fascinating. But that in itself is presumably because sex is such a big deal in evolutionary terms. We’ve evolved to find it fascinating.

I agree that the centrality of sex differences is a big part of why the field is controversial. A lot of non-evolutionary psychologists seem to want to say “Well, I don’t like that evolutionary psychology; I just like the other stuff, the G-rated, high-brow stuff.” But I don’t think we should downplay the sexy stuff just because it makes some people uncomfortable. Mating behavior and sex differences are among the most conspicuous and important products of natural selection in our species. If people don’t like that, too bad!

LP: Evolutionary pschology has been criticised by many on the left for supporting sexist stereotypes about men and women. And some in online conservative circles seem indeed to mention evolutionary ideas to support their criticism of left-wing feminism. What do you think of these debates and the place evolutionary psychology has taken in some political discussions around sexual differences?

It’s tiresome! I’d rather shut out the politics completely. I’m not sympathetic to either side, to be honest. I’m currently writing a book about the evolution of sex differences, and one of my arguments is that traditionalists and progressives both get sex differences wrong. Traditionalists exaggerate and moralize the differences; progressives minimize or deny them – or they moralize the absence of sex differences. Both sides are too quick to reject claims they don’t like, and both try to ground policy prescriptions in muddled views of men and women: conservatives in old-fashioned stereotypes of the sexes as naturally radically different; progressives in more recent stereotypes of the sexes as naturally the same.

Because academia is dominated by progressives, we tend to hear critiques of traditional views of sex differences rather than progressive ones. But both views are erroneous, and both cause serious problems for society. To my mind, the question isn’t whether people on the left like a given claim or not, or whether people on the right do; it’s whether the claim is true. People’s political preferences shouldn’t figure into the equation.

LP: Over the last few years, there has been a replication crisis in psychology that has really shaken the pillars of psychology with many classical results included in textbooks found not to replicate, sometimes because they were fabricated in the first place. How has evolutionary psychology fared in this storm that struck psychology?

The central results of evolutionary psychology have stood up well: the results informed by theories from evolutionary biology and comparable to tendencies seen in other species. Perhaps in part because the field has been somewhat controversial, we’ve got a good track record of replicating our core results, including sex differences in interest in casual sex, sex differences in mate preferences, and so on.

But we certainly haven’t emerged from the replication crisis unscathed. Various findings that we used to think were well-established are now sitting under a big question mark, and some have been largely discredited. Among those on the chopping block are the idea that women are more attracted to men other than their current partners when they’re in the fertile phase of their cycle, and the idea that humans are adapted to extremely high levels of promiscuous mating and infidelity. Most evolutionary psychologists aren’t anywhere near as confident in these hypotheses as they used to be – and many, including myself, have basically abandoned them.

LP: What do you think are the interesting questions ahead for evolutionary psychology and where do you see the discipline go?

I’d point to three main growth areas in evolutionary psychology. The first is the study of the evolution of emotions – in particular the social emotions. Among the fascinating conclusions emerging from this area are: (1) that anger is a reaction to people valuing you less than you think they should, which motivates efforts to encourage better treatment, and (2) that shame is a response to a drop in status, which motivates efforts to get back into people’s good books.

The second hot topic, which I discuss in depth in The Ape That Understood the Universe, concerns one of our defining features as a species: culture. Questions tackled by researchers in this area include the following. How did we evolve our cultural capacity? How does culture itself evolve? And how have we evolved biologically in response to the culture we’ve created (gene-culture coevolution)?

The third area – one that’s less exciting but no less important – is that we’re spring cleaning the field in the wake of the replication crisis. By pruning away some of the sillier, less robust claims linked to evolutionary psychology, the field will ultimately become much stronger – and it’ll be a lot harder for critics to dismiss it in its entirety just by pointing to its weaker claims.

LP: Personally, I think that an evolutionary perspective is just a natural and necessary background in behavioural science because life is the product of evolution. In his old classic “How the Mind Works”, Pinker made the point that when you see something designed, like a watch, it is normal to ask “What is it intended to do?” to understand it. Evolution is like a designer, even if it is an impersonal and blind one – to refer to Dawkins' expression “blind watchmaker”. So it is natural to ask functional questions when studying human behaviour: why are we doing this? When you see a strange behaviour, it is a good start to ask “what are the good reasons behind this behaviour” instead of labelling people as silly, noisy or gullible.

As an economist, I would very much like to see greater cross-fertilisation between evolutionary psychologists and economics. Some of the most interesting works in evolutionary psychology like those of Trivers and Tooby and Cosmides have leveraged ideas from game theory. Game theory can really help provide deep insights about cooperation, conflict, and coalition building. The recent progress in economic theory of information that studies optimal decisions when information is costly can also offer a trove of novel insights to evolutionary psychologists. What do you think is the likely evolution of the field ahead, in its relation to other behavioural sciences, like economics and possibly in relation to the broader field of psychology?

I agree that an evolutionary perspective is a natural and necessary backdrop to psychology and the social sciences, and that it makes sense to ask about the possible functions of any given behavior. But I immediately want to follow up with a bunch of cautions and qualifications!

First, plenty of apparently designed traits and tendencies in our species are products of individual learning and culture, rather than natural selection. Selection isn’t the only source of apparent design in Homo sapiens.

Second, although I agree that we shouldn’t assume that behavior is silly, noisy, or gullible, I suspect that a lot of it is. Plenty of behavior, for instance, is a product of evolutionary mismatch: that is, mismatch between the environment in which we spent the bulk of our evolution and our current environment. Obesity is the classic example: Our love of sweet food wasn’t a problem for our hunter-gatherer forebears, but in our modern, sugar-soaked world, it is. Even when mismatch isn’t involved, individual behaviors aren’t necessarily adaptive. Rather than asking why a particular behavior in a particular situation might be adaptive, I prefer to ask why the emotions and motivations driving that behavior might have been adaptive for our ancestors, on average, throughout the period in which those emotions and motivations evolved.

Third, the fact that a behavior is rational with respect to the goal of gene proliferation doesn’t mean it’s necessarily rational with respect to goals like happiness, utility maximization, or making the world a better place. We need to draw a clear distinction between adaptive in the evolutionary sense of the word and adaptive in the everyday sense or the economist’s sense.

Fourth and finally, although I agree that some of the most important findings in evolutionary psychology have drawn on insights from game theory, I also see tensions between economic and evolutionary approaches. Both ask “What is the reason behind this behavior?” but their answers are often very different. With evolutionary explanations, the putative reason is that the behavior maximized our ancestors’ inclusive fitness in past environments; with economic ones, it’s that the behavior is useful in terms of self-interest today. So although I’m sure there’ll be some further cross-pollination, my guess is that, for the most part, evolutionary and economic analyses will maintain their own spheres of influence. In explaining basic emotions and motivations, an evolutionary analysis may reign supreme. In explaining why people make the specific choices they do in modern societies, however, an economic analysis may often claim the crown.

This is the second post in a series of threes posts on the value of taking an evolutionary perspective when trying to understand human behaviour.

Reading the interview, I'm struck by the weakness of the evidence for behavior in humans, such as kin-specific altruism and sex differences in behavior, that are easily observable in most animal species of which I am aware, where there is obvious kin preference and plenty of sexual dimorphism.

here are very few instances of interesting human universals here: rather we have statistical evidence of differences in means

To offer a couple of counterpoints,

1. Humans have an amazing willingness to extend altruism way beyond the point where it can serve any evolutionary purpose, to entire nations, social classes, religious groupings and, ideally, humanity as a whole. Nationalism is much easier to observe than, for example, preference for full siblings over half-siblings

2. Differences in behavior between men and women seem to be mostly statistical and dependent on a common environment. This is also true of physical characteristics like height and weight.

This interview with an esteemed evolutionary psychologist seemed like a fine occasion to harshly critique his discipline. The outrageous and unironic hubris of his book's title ("The Ape that Understood the Universe") is so revealing that I'm almost tempted to end the critique here 😬 But that won't do.

https://substack.com/@cozyshark/note/c-82288436?r=1y1e12

I'd welcome some lively discussion with anyone interested -- but especially those who happen to disagree.